PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

World Happiness Report 2023: India Among World's Saddest Nations

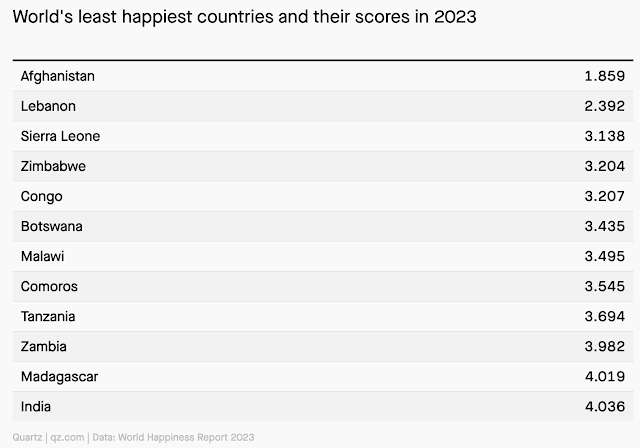

India occupies 126th position among 137 nations ranked in the World Happiness Report 2023 released by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network. In South Asia, Pakistan (score 4.555) ranks 108, Sri Lanka 112, Bangladesh (4.282) 118 and India 126 (4.036). Only Taliban-ruled Afghanistan ranks worse at 137. Finland is the happiest nation in the world, followed by Denmark and Iceland in 2nd and 3rd place.

|

| Least Happy Countries in 2023. Source: Quartz |

|

| Bottom Third Countries in World Happiness Rankings. Source: World H... |

The latest country rankings show life evaluations (answers to the Cantril ladder question) for each country, averaged over a 3 year period from 2020-2022. The Cantril ladder asks respondents to think of a ladder, with the best possible life for them being a 10 and the worst possible life being a 0. They are then asked to rate their own current lives on that 0 to 10 scale. The rankings are from nationally representative samples for the years 2020-2022.

|

| World Happiness Map 2023. Source: Visual Capitalist |

Happiness Scores Trend:

After climbing to a high of 5.65 in 2019, Pakistan's happiness scores have declined in recent years, reaching a low of 4.52 during the Covid pandemic. The most recent value is 4.555 for 2023.

|

| Recent Happiness Scores in Pakistan. Source: The Global Economy |

India's happiness scores have been declining every year since 2013, reaching a low of 3.78 during the Covid pandemic. The most recent value is 4.036 for 2023.

|

| Recent Happiness Scores in India. Source: The Global Economy |

Causes of Unhappiness:

Lack of social connections during covid lockdown, along with severe unemployment, high inflation and healthcare worries, took a toll on mental health of Indians, according to the experts quoted by the Indian media.

|

| Suicide Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: World Bank |

Rising Suicides:

Indian experts' observations are supported by the Indian government data showing a marked increase in suicide rate in India. India saw the highest suicide rate (of 12 suicides per 100,000 population) since the beginning of this century, according to The Hindu. Experts say a lot of suicides would have gone unreported and that the numbers and suicide rates could have gone up in 2022 as well.

|

| Suicide Rate in India. Source: The Hindu |

High Unemployment:

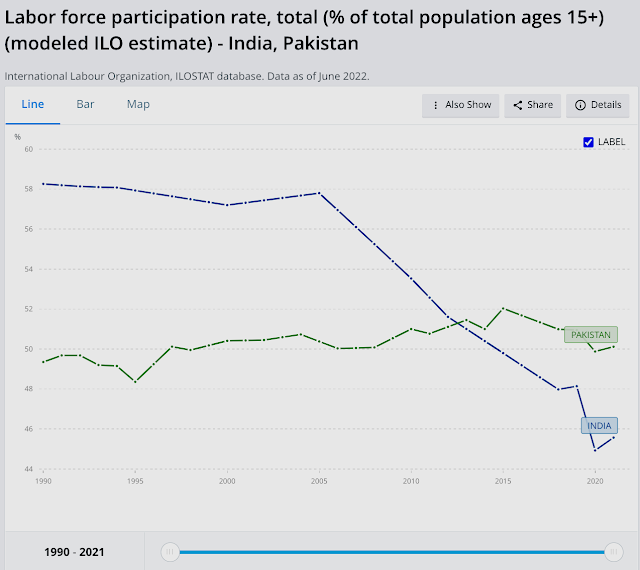

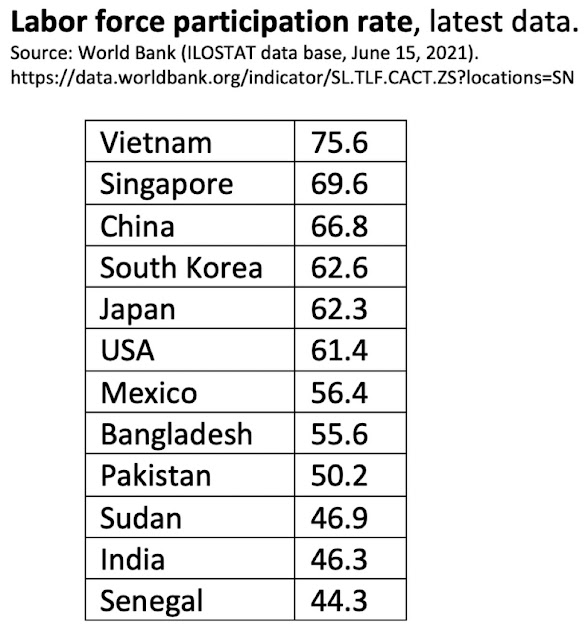

India's unemployment rate rose to 7.45% in February 2023 from 7.14% in the previous month, according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). CMIE’s weekly labor market analysis showed a marginal improvement in India’s labor participation rate to 39.92% in February compared to 39.8% in January 2023 resulting in an increase in the labour force from 440.8 million to 442.9 million.

"India’s LPR is much lower than global levels. According to the World Bank, the modeled ILO estimate for the world in 2020 was 58.6 per cent. The same model places India’s LPR at 46 percent. India is a large country and its low LPR drags down the world LPR as well. Implicitly, most other countries have a much higher LPR than the world average. According to the World Bank’s modeled ILO estimates, there are only 17 countries worse than India on LPR. Most of these are middle-eastern countries. These are countries such as Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Syria, Senegal and Lebanon. Some of these countries are oil-rich and others are unfortunately mired in civil strife. India neither has the privileges of oil-rich countries nor the civil disturbances that could keep the LPR low. Yet, it suffers an LPR that is as low as seen in these countries".

|

| Labor Participation Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: World Bank... |

|

| Labor Participation Rates for Selected Nations. Source: World Bank/ILO |

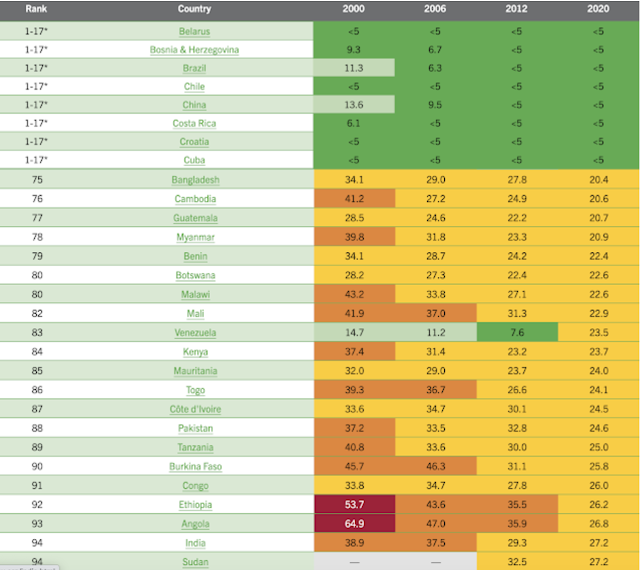

Youth unemployment for ages15-24 in India is 24.9%, the highest in South Asia region. It is 14.8% in Bangladesh 14.8% and 9.2% in Pakistan, according to the International Labor Organization and the World Bank.

|

| Youth Unemployment in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Source: ILO, WB |

In spite of the headline GDP growth figures highlighted by the Indian and world media, the fact is that it has been jobless growth. The labor participation rate (LPR) in India has been falling for more than a decade. The LPR in India has been below Pakistan's for several years, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

|

| Indian GDP Sectoral Contribution Trend. Source: Ashoka Mody |

|

| Indian Employment Trends By Sector. Source: CMIE Via Business Standard |

|

| World Hunger Rankings 2020. Source: World Hunger Index Report |

Hunger and malnutrition are worsening in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia because of the coronavirus pandemic, especially in low-income communities or those already stricken by continued conflict.

India has performed particularly poorly because of one of the world's strictest lockdowns imposed by Prime Minister Modi to contain the spread of the virus.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid1...

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Cou...

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade De...

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 22, 2023 at 4:23pm

-

#Tech #Startup Layoffs in #India. Over 36,400 people lost their jobs in India in the last couple of years. 5 companies have laid off 75% of their workforce. #Indian startups which laid off workers include #Byju, #UpAcademy, #Ola. #economy #unemployment

https://www.livemint.com/news/india/thousands-have-lost-jobs-in-ind...

Over 36,400 people lost their jobs in India in the last couple of years, as per the latest data from layoff.fyi. Nine companies, including Lido Learning, SuperLearn and GoNuts, have laid off 100% of its workforce. According to the website that tracks tech sector job cuts, five companies laid off 70-75% of its workforce. Such companies include GoMechanic, PhableCare and MFine.

Byju’s is leading the number of layoffs with 4,000 employees losing their jobs at the company. WhiteHat Jr laid off 1,800 employees in January 2021 and then 300 in June 2022. Bytedance terminated 1,800 employees in January 2021. In June 2020, Paisabazaar let go 1,500 people, 50% of its workforce.

Ola has laid off its employees four times since May 2020. In May 2020, it laid off 1,400 employees while it sacked 1,000 people in July 2022. In September 2022, it asked 200 people to leave and terminated 200 employees again in January 2023.

Unacademy has laid off 1,500 employees so far, all of it came in 2022. The layoff came in three phases; 1,000 in April, 150 in June and 350 in November.

On the global front, 503 tech companies have laid off 148,165 employees so far this year. The year 2022 was challenging for the technology industry and startups. At least 1.6 lakh workers lost their jobs in 2022, and the year 2023 has begun on a similar note.

Amazon has contributed to the worsening outlook for the technology industry by terminating an additional 9,000 employees. This comes after they had previously fired 18,000 employees. Meanwhile, a significant number of other companies have also laid off a substantial amount of workers this year, with almost 1.5 lakh individuals being affected to date.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 23, 2023 at 10:26am

-

Why So Sad? #India’s Rank On #WorldHappinessIndex2023 Saddens Industrialist Harsh Goenka. “I am saddened to see India perform miserably in what I believe is the most important parameter to reflect the state of the nation ‘Global Happiness Index 2023’" https://www.news18.com/buzz/why-so-sad-indias-rank-on-world-happine...

he World Happiness Report is out and the result has saddened a lot of Indians. Among them is industrialist Harsh Goenka, who is not satisfied with the country’s “miserable” position on the index. India is ranked 126th among 146 nations, with a score of 4.00 on a scale of 0 to 10. The annual United Nations-sponsored index is based on people’s own assessment of their happiness, economic and social data. India’s position is a sharp jump from the 136th spot that India occupied last year, yet Harsh Goenka feels that much more needs to be done. The RPG Enterprises chairman, in a recent tweet, asked what could be done to better the situation.

“I am saddened to see India perform miserably in what I believe is the most important parameter to reflect the state of the nation ‘Global Happiness Index 2023’. What is the reason and what should we do about it?” Harsh Goenka wrote while sharing some data of the Global Happiness Index 2023.

Many users were just as concerned as Harsh Goenka and put forward many reasons as a possibility for India’s low rank in the report. “We need to improve our work-family-fitness balance,” one person suggested.

Some stated that there was too much divisiveness and hate in India these days.

A few users cited price rises as the reason for unhappiness. “Low per capita income and rising cost could be a reason,” a comment read.

Others advised newer ways to achieve work-life balance. “More than monetary, I believe that recreation is a big part of this problem… For an Indian the only sort of relief from the problems of life are cinema and cricket. We need to think of new ways to balance out work and life,” an individual noted.

But quite a few people questioned the data collection of the Global Happiness Index, calling it “biased.”

“Have you looked into how it is calculated and the integrity of the data?” another person asked.

India’s neighbours have fared better when it comes to the World Happiness Report. Pakistan is at 108th place, while Bangladesh occupies 118th spot. Nepal is 78th and Sri Lanka is ranked 112th on the index.

As per the World Happiness Report 2023, Finland is the happiest country in the world. Denmark and Iceland occupied the second and third positions. Afghanistan is at the bottom of the table once again. Since 2020, the country has remained at the lowest spot on the index. The World Happiness Report has been published yearly since 2012.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 23, 2023 at 2:45pm

-

#India’s #Modi has a problem: high #economic #growth but few #jobs. Persistently high #unemployment poses #election challenge as youth stuck in menial #labor that does not match skills. No wonder India ranks among world's saddest nations. #Happiness https://www.ft.com/content/6886014f-e4cd-493c-986b-1da2cfc8cdf2

Kiran VB, 29, a resident of India’s tech capital Bangalore, had hoped to work in a factory after finishing high school. But he struggled to find a job and started working as a driver, eventually saving up over a decade to buy his own cab.

“The market is very tough; everybody is sitting at home,” he said, describing relatives with engineering or business degrees who also failed to find good jobs. “Even people who graduate from colleges aren’t getting jobs and are selling stuff or doing deliveries.”

His story points to an entrenched problem for India and a growing challenge for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government as it seeks re-election in just over a year’s time: the country’s high-growth economy is failing to create enough jobs, especially for younger Indians, leaving many without work or toiling in labour that does not match their skills.

The IMF forecasts India’s economy will expand 6.1 per cent this year — one of the fastest rates of any major economy — and 6.8 per cent in 2024.

However, jobless numbers continue to rise. Unemployment in February was 7.45 per cent, up from 7.14 per cent the previous month, according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

“The growth that we are getting is being driven mainly by corporate growth, and corporate India does not employ that many people per unit of output,” said Pronab Sen, an economist and former chief adviser to India’s Planning Commission.

“On the one hand, you see young people not getting jobs; on the other, you have companies complaining they can’t get skilled people.”

Government jobs, coveted as a ticket to life-long employment, are few in number relative to India’s population of nearly 1.4bn, Sen said. Skills availability is another issue: many companies prefer to hire older applicants who have developed skills that are in demand.

“A lot of the growth in India is driven by finance, insurance, real estate, business process outsourcing, telecoms and IT,” said Amit Basole, professor of economics at Azim Premji University in Bangalore. “These are the high-growth sectors, but they are not job creators.”

Figuring out how to achieve greater job growth, particularly for young people, will be essential if India is to capitalise on a demographic and geopolitical dividend. The country has a young population that is set to surpass China’s this year as the world’s largest. More companies are looking to redirect supply chains and sales away from reliance on Chinese suppliers and consumers.

India’s government and states such as Karnataka, of which Bangalore is the capital, are pledging billions of dollars of incentives to attract investors in manufacturing industries such as electronics and advanced battery production as part of the Modi government’s “Make in India” drive.

The state also recently loosened labour laws to emulate working practices in China following lobbying by companies including Apple and its manufacturing partner Foxconn, which plans to produce iPhones in Karnataka.

However, manufacturing output is growing more slowly than other sectors, making it unlikely to soon emerge as a leading generator of jobs. The sector employs only about 35mn, while IT accounts for a scant 2mn out of India’s formal workforce of about 410mn, according to the CMIE’s latest household survey from January to February 2023.

According to a senior official in Karnataka, highly skilled applicants with university degrees are applying to work as police constables.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 23, 2023 at 2:46pm

-

#India’s #Modi has a problem: high #economic #growth but few #jobs. Persistently high #unemployment poses #election challenge as youth stuck in menial #labor that does not match skills. No wonder India ranks among world's saddest nations. #Happiness https://www.ft.com/content/6886014f-e4cd-493c-986b-1da2cfc8cdf2

The Modi government has shown signs of being attuned to the issue. In October, the prime minister presided over a rozgar mela, or an employment drive, where he handed over appointment letters for 75,000 young people, meant to showcase his government’s commitment to creating jobs and “skilling India’s youth for a brighter future”.

But some opposition figures derided the gesture, with the Congress party president Mallikarjun Kharge saying the appointments were “just too little”. Another politician called the fair “a cruel joke on unemployed youths”.

Rahul Gandhi, the scion of the family behind the Congress party, has signalled that he intends to make unemployment a point of attack for the upcoming election, in which Modi is on track to win a third term.

“The real problem is the unemployment problem, and that’s generating a lot of anger and a lot of fear,” Gandhi said in a question-and-answer session at Chatham House in London last month.

“I don’t believe that a country like India can employ all its people with services,” he added.

Ashoka Mody, an economist at Princeton University, invoked the word “timepass”, an Indian slang term meaning to pass time unproductively, to explain another phenomenon plaguing the jobs market: underemployment of people in work not befitting their skills.

“There are hundreds of millions of young Indians who are doing timepass,” said Mody, author of India is Broken, a new book critiquing the economic policies of successive Indian governments since independence. “Many of them are doing so after multiple degrees and colleges.”

Dildar Sekh, 21, migrated to Bangalore after completing a high school course in computer programming in Kolkata.

After losing out in the intense competition for a government job, he ended up working at Bangalore’s airport with a ground handling company that assists passengers in wheelchairs, for which he is paid about Rs13,000 ($159) per month.

“The work is good, but the salary is not good,” said Sekh, who dreams of saving enough money to buy an iPhone and treat his parents to a helicopter ride.

“There is no good place for young people,” he added. “The people who have money and connections are able to survive; the rest of us have to keep working and then die.”

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 24, 2023 at 8:09am

-

From Salman Ansari:

India is one of the rare countries in the world where GDP growth is inversely proportional to happiness. It means either one of two things. 1) India’s growth numbers are fictitious 2) India’s growth has disproportionately benefited only a tiny upper-class / upper-caste elite

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 25, 2023 at 10:26am

-

Most Indians reject all international rankings in which India performs poorly.

Indian government dismissed India's low ranking in World Hunger Index even though it was based entirely on India's official data.

Please read below:

https://www.logically.ai/articles/indias-hunger-problem-ghi

Regardless of the GHI rankings, the Indian government’s own data shows that India has a serious hunger problem, at least when it comes to children.

According to the fifth National Family Health Survey (NFHS-V) for 2019-21, the percentage of children wasted under five years was 19.3 percent. Child stunting in the same age bracket was at 35.5 percent. These figures are used for India’s assessment in the GHI, with it faring the highest in child wasting.

While there was slight improvement by under three percentage points on both these indicators compared to 2015 to 2016, the data included concerning findings on ‘severe’ malnutrition among children. Analysis of district-level NFHS data reveals that almost half of Indian districts recorded an increase in severe wasting or severe acute malnutrition between 2015-2016 and 2019-2021. Additionally, data shows anaemia levels among children increased by almost ten percent in the same time period.

“We do not need the GHI to know that India has a serious problem of undernutrition. The levels of stunting are high and are not declining fast enough. One reason for the slow progress on this is our unwillingness to acknowledge the seriousness of this issue," Khera said.

The government’s response to the GHI can be seen as an indication of dismissing the issue. The central government argues that it is undertaking extensive programmes to ensure food security such as distribution of additional foodgrains to 80 crore beneficiaries from March 2020. But activists and experts allege that this doesn’t solve the problem of poor nutrition.

Nearly 71 percent Indians cannot afford a healthy diet, even with public programmes factored in, Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) and Down To Earth reported in June this year.

“Close to a 100 million people stand excluded out of India's public distribution system since the government is still using the 2001 population data from the Census rather than updated estimates for 2022,” said Biraj Patnaik, former Principal Adviser to the Commissioners of the Supreme Court in the Right to Food case. “Rather than quibbling over global rankings, as a country we must address the underlying causes of malnutrition which go beyond food and cover other social determinants” Patnaik said.

“Of course India has the largest food security programme, but the evidence is suggesting it's not enough. Moreover, after more than 75 years of Independence, our aspiration cannot just be improving cereal consumption; we need to work on providing decent quality of food to our people," Prasad said.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 27, 2023 at 2:26pm

-

#SouthKorean government was this week forced to rethink a plan that would have raised its cap on #workinghours to 69 per week, up from the current limit of 52, after sparking a backlash among Millennials and Generation Z workers. #SouthKorea https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/18/asia/south-korea-longer-work-week-de...

Shorter workweeks to boost employee mental health and productivity may be catching on in some places around the world, but at least one country appears to have missed the memo.

The South Korean government was this week forced to rethink a plan that would have raised its cap on working hours to 69 per week, up from the current limit of 52, after sparking a backlash among Millennials and Generation Z workers.

Workers in the east Asian powerhouse economy already face some of the longest hours in the world – ranking fourth behind only Mexico, Costa Rica and Chile in 2021, according to the OECD – and death by overwork (“gwarosa”) is thought to kill scores of people every year.

Yet the government had backed the plan to increase the cap following pressure from business groups seeking a boost in productivity – until, that is, it ran into vociferous opposition from the younger generation and labor unions.

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol’s senior secretary said Wednesday the government would take a new “direction” after listening to public opinion and said it was committed to protecting the rights and interests of Millennial, Generation Z and non-union workers.

Raising the cap had been seen as a way of addressing the looming labor shortage the country faces due to its dwindling fertility rate, which is the world’s lowest, and its aging population.

But the move was widely panned by critics who argued tightening the screw on workers would only make matters worse; experts frequently cite the country’s demanding work culture and rising disillusionment among younger generations as driving factors in its demographic problems.

It was only as recently as 2018 that, due to popular demand, the country had lowered the limit from 68 hours a week to the current 52 – a move that at the time received overwhelming support in the National Assembly.

The current law limits the work week to 40 hours plus up to 12 hours of compensated overtime – though in reality, critics say, many workers find themselves under pressure to work longer.

“The proposal does not make any sense… and is so far from what workers actually want,” said Jung Junsik, 25, a university student from the capital Seoul who added that even with the government’s U-turn, many workers would still be pressured to work beyond the legal maximum.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 28, 2023 at 6:39pm

-

India slipping on way to meeting UN-mandated SDGs: CSE-DTE

https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/climate-change/india-slipping-o...

https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/profiles/pakistan

https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/profiles/india

Country (India) facing challenges in 11 of the 17 SDGs; states’ individual performances ranked as well (Pakistan facing challenges in 12 of 17 SDGs)

India has been stumbling over meeting the United Nations-mandated sustainable development goals (SDG). Over the past five years, it has slipped nine spots — ranking 121 in 2022, according to an annual report by Down To Earth, the fortnightly magazine by New Delhi-based non-profit Centre for Science and Environment.

India is behind its neighbours Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bangladesh and Pakistan was lagging close behind at 125. The deadline for the goals is 2030, which is looming ahead — but India is facing challenges in 11 of the 17 SDGs, according to State of India’s Environment 2023 (SoE), released on March 23, 2023.

The 2023 report covered an extensive gamut of subject assessments, ranging from climate change, agriculture and industry to water, plastics, forests and biodiversity.

The report looked at states’ performances as well. “An alarmingly high number of states have slipped in their performance of SDGs 4, 8, 9, 10 and 15,” said Richard Mahapatra, managing editor of DTE and one of the editors of the SoE.

These numbers refer to the goals on quality education; decent work and economic growth; industry, innovation and infrastructure; reduced inequalities; and life on land, respectively.

In SDG 4 (quality education), for instance, 17 states saw a dip in their performance between 2019 and 2020. SDG 15 — life on land — has 25 states performing below average.

The goal on clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) has become more distant for 15 states, while 22 states are slipping in SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth).

Concurrently, there has been improvement by states as well in several goals — SDGs 1 (no poverty), 2 (zero hunger), 3 (good health and well-being), 5 (gender equality), 7 (affordable and clean energy), 11 (sustainable cities and communities) and 12 (responsible consumption and production).

“All the data that we are using here is from credible, and in many cases, from the government’s own sources,” said Mahapatra.

DTE’s research team says that India’s ranking has been taken from the SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2022 by Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network for the time period 2017-2022.

The state-level ranking is based on the government think tank NITI Aayog’s SDG India Index Report 2020-21. Here, the DTE team has analysed the 2020 and 2019 scores.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 30, 2023 at 4:56pm

-

Hype over #India’s #economic boom is dangerous myth masking real problems. It’s built on a disingenuous numbers game.

No silver bullet that will fix weak job creation, a small, uncompetitive #manufacturing sector & gov’t schemes fattening corporate profits

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

by Ashoka Mody

Indian elites are giddy about their country’s economic prospects, and that optimism is mirrored abroad. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that India’s GDP will increase by 6.1 per cent this year and 6.8 per cent next year, making it one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

Other international commentators have offered even more effusive forecasts, declaring the arrival of an Indian decade or even an Indian century.

In fact, India is barrelling down a perilous path. All the cheerleading is based on a disingenuous numbers game. More so than other economies, India’s yo-yoed in the three calendar years from 2020 to 2022, falling sharply twice with the emergence of Covid-19 and then bouncing back to pre-pandemic levels. Its annualised growth rate over these three years was 3.5 per cent, about the same as in the year preceding the pandemic.

Forecasts of higher future growth rates are extrapolating from the latest pandemic rebound. Yet, even with pandemic-related constraints largely in the past, the economy slowed in the second half of 2022, and that weakness has persisted this year. Describing India as a booming economy is wishful thinking clothed in bad economics.

Worse, the hype is masking a problem that has grown in the 75 years since independence: anaemic job creation. In the next decade, India will need hundreds of millions more jobs to employ those who are of working age and seeking work. This challenge is virtually insurmountable considering that the economy failed to add any net new jobs in the past decade, when 7 million to 9 million new jobseekers entered the market each year.

This demographic pressure often boils over, fuelling protests and episodic violence. In 2019, 12.5 million people applied for 35,000 job openings in the Indian railways – one job for every 357 applicants. In January 2022, railway authorities announced they were not ready to make the job offers. The applicants went on a rampage, burning train cars and vandalising railway stations.

With urban jobs scarce, tens of millions of workers returned during the pandemic to eking out meagre livelihoods in agriculture, and many have remained there. India’s already-distressed agriculture sector now employs 45 per cent of the country’s workforce.

Farming families suffer from stubbornly high underemployment, with many members sharing limited work on plots rendered steadily smaller through generational subdivision. The epidemic of farmer suicides persists. To those anxiously seeking support from rural employment-guarantee programmes, the government unconscionably delays wage payments, triggering protests.

For far too many Indians, the economy is broken. The problem lies in the country’s small and uncompetitive manufacturing sector.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 30, 2023 at 4:57pm

-

India is Broken

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

by Ashoka Mody

Since the liberalising reforms of the mid-1980s, the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP has fallen slightly to about 14 per cent, compared to 27 per cent in China and 25 per cent in Vietnam. India commands less than a 2 per cent global share of manufactured exports, and as its economy slowed in the second half of 2022, the manufacturing sector contracted further.

Yet it is through exports of labour-intensive manufactured products that Taiwan, South Korea, China and now Vietnam came to employ vast numbers of their people. India, with its 1.4 billion people, exports about the same value of manufactured goods as Vietnam does with 100 million people.

Those who believe that India stands at the cusp of greatness usually focus on two recent developments. First, Apple contractors have made initial investments to assemble high-end iPhones in India, leading to speculation that a broader move away from China by manufacturers will benefit India despite the country’s considerable quality-control and logistical problems.

while such an outcome is possible, academic analysis and media reports are discouraging. Economist Gordon H. Hanson says Chinese manufacturers will move labour-intensive manufacturing from the country’s expensive coastal hubs to its less-developed interior, where production costs are lower.

Moreover, investors moving out of China have gone mainly to Vietnam and other countries in Southeast Asia, which like China are members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. India has eschewed membership in this trade bloc because its manufacturers fear they will be unable to compete once other member states gain easier access to the Indian market.

As for US producers pulling away from China, most are “near-shoring” their operations to Mexico and Central America. Altogether, while some investment from this churn could flow to India, the fact remains that inward foreign investment fell year on year in 2022.

The second source of hope is the Indian government’s Production-Linked Incentive Schemes, which were introduced in early 2021 to offer financial rewards for production and jobs in sectors deemed to be of strategic value. Unfortunately, as former Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram G. Rajan and his co-authors warn, these schemes are likely to end up merely fattening corporate profits like previous sops to manufacturers.

India’s run with start-up unicorns is also fading. The sector’s recent boomrelied on cheap funding and a surge of online purchases by a small number of customers during the pandemic. But most start-ups have dim prospects for achieving profitability in the foreseeable future. Purchases by the small customer base have slowed and funds are drying up.

Looking past the illusion created by India’s rebound from the pandemic, the country’s economic prognosis appears bleak. Rather than indulge in wishful thinking and gimmicky industrial incentives, policymakers should aim to power economic development through investments in human capital and by bringing more women into the workforce.

India’s broken state has repeatedly avoided confronting long-term challenges and now, instead of overcoming fundamental development deficits, officials are seeking silver bullets. Stoking hype about an imminent Indian century will merely perpetuate the deficits, helping neither India nor the rest of the world.

Ashoka Mody, visiting professor of international economic policy at Princeton University, is the author of India is Broken: A People Betrayed, Independence to Today. Copyright: Project Syndicate

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Has Pakistan Destroyed India's S-400 Air Defense System at Adampur?

Pakistan claims its air force (PAF) has destroyed India's high-value Russian-made S-400 air defense system (ADS) located at the Indian Air Force (IAF) Adampur air base. India has rejected this claim and posted pictures of Prime Minister Narendra Modi posing in front of its S-400 rocket launchers in Adampur. Meanwhile, there are reports that an Indian S-400 operator, named Rambabu Kumar Singh, was killed at about the time Pakistan claims to have hit it. Pakistan is believed to have targeted…

ContinuePakistan Downs India's French Rafale Fighter Jets in History's Largest Aerial Battle

Pakistan Air Force (PAF) pilots flying Chinese-made J10C fighter jets shot down at least two Indian Air Force's French-made Rafale jets in history's largest ever aerial battle involving over 100 combat aircraft on both sides, according to multiple media reports. India had 72 warplanes on the attack and Pakistan responded with 42 of its own, according to Pakistani military. The Indian government has not yet acknowledged its losses but senior French and US intelligence officials have …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on May 9, 2025 at 11:00am — 32 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network