PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

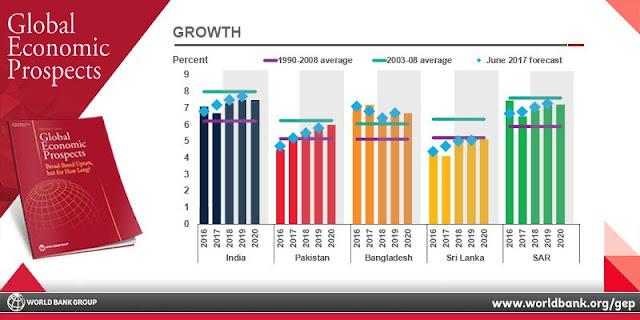

World Bank: Pakistan Outperforming Emerging Economies Average

The World Bank sees Pakistan's GDP to grow 5.5% in current fiscal year 2017-18 ending in June 2018, a full percentage point faster than the 4.5% average GDP growth for Emerging and Developing Economies (EMDEs) that include Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Nigeria and Russia among others. However, Pakistan economic growth continues to lag growth forecast for regional economies of India and Bangladesh. The report also highlights the issue to growing trade deficit and current account gap that could lead to yet another balance of payments crisis for Pakistan requiring another IMF bailout.

Pakistan GDP Growth:

Here's an excerpt of the January 2018 World Bank report titled "Global Economic Prospects" as it relates to Pakistan:

"In Pakistan, growth continued to accelerate in FY2016/17 (July-June) to 5.3 percent, somewhat below the government’s target of 5.7 percent as industrial sector growth was slower than expected. Activity was strong in construction and services, and there was a recovery in agricultural production with a return of normal monsoon rains. In the first half of FY2017/18, activity has continued to expand, driven by robust domestic demand supported by strong credit growth and investment projects related to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Meanwhile, the current account deficit widened to 4.1 percent of GDP compared to 1.7 percent last year, amid weak exports and buoyant imports."

Growing External Account Imbalance:

The report correctly points out the problem of growing current account deficit that could turn into a balance of payments crisis unless the trade deficits are brought under control. Recent trends in the last three months do offer some hope with December 2017 exports up 15% while imports increased 10%. Exports in November increased 12.3%.

Along with double digit increase in exports in the last two months, Pakistan received remittances amounting to $1.724 billion in December 2017, 8.72% higher compared with $1.585 billion the country received in the same month of the previous year, according to data released by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), as reported by Express Tribune.

Summary:

Pakistan's economic growth is continuing to accelerate amid rising rising investments led by China-Pakistan Economic Corridor related infrastructure and energy related projects. The World Bank sees Pakistan's GDP to grow 5.5% in current fiscal year 2017-18 ending in June 2018, a full percentage point faster than the 4.5% average GDP growth for Emerging and Developing Economies (EMDEs) that include Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Nigeria and Russia among others. However, Pakistan economic growth continues to lag growth forecast for regional economies of India and Bangladesh. The report also calls attention to the expanding current account gap as a matter of concern that must be taken seriously by the government to avoid yet another return to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Related Links:

CPEC is Transforming Least Developed Parts of Pakistan

Per Capita Income in "Failed State" of Pakistan Rose 22% in 5 Years

Credit Suisse Wealth Report 2017

Pakistan Translates GDP Growth to Citizens' Well-being

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 12, 2018 at 10:38am

-

India May Be The World's Fastest Growing Economy, But Regional Disparity Is A Serious Challenge

https://www.forbes.com/sites/salvatorebabones/2018/01/10/india-may-...

All of India is poor. The GDP per capita of Delhi, the National Capital Territory with a population of 20-25 million, is roughly equal to that of Indonesia at around $4,000. Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, India's poorest states, are on a par with sub-Saharan Africa (less than $1,000). And geographical disparities matter much more in India than in other large countries. In the United States, the richest state (Massachusetts) has roughly twice the GDP of the poorest (Mississippi). In China the ratio is 4-1 between Beijing and Gansu. In India, Delhi's GDP per capita is eight times that of Bihar.

In southern India, Bangalore is famous as India's technology capital, home to companies like Flipkart, Infosys and Wipro, as well as the Indian Institute of Science, India's top-ranked university. Yet the state of which Bangalore is the capital, Karnataka, has a GDP per capita of around $2,400, roughly the same as Papua New Guinea. Tech entrepreneurs drive to work past open sewers and shantytowns. The real Silicon Valley in California has similar problems with inequality, but the scale of inequality in Bangalore is something completely different.

If India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi is serious about his election slogan Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas (Together with All, Progress for All), then reducing India's regional disparities should be high on his agenda. Modi's GST reform was an indispensable measure to reduce internal trade barriers, and his highway construction program is a good start toward knitting the country together. But India will need a lot more regional growth and much more generous fiscal transfers to its poorer states to overcome its extreme regional disparities.

India as a whole won't reach middle-income status until it unites its poorer states into the same Incredible India economy as the rest of the country. That's a challenge beyond the remit of any one government. But Modi and his BJP government swept to power in 2014 on the votes of India's poorest states, of the people most excluded from India's economic growth. If Modi wants to retain his majority in the next parliamentary elections, he would do well to focus on reducing the regional disparities that played such a key role in bringing him to office in the first place.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 12, 2018 at 5:02pm

-

https://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21734454-should-worry-both-g...

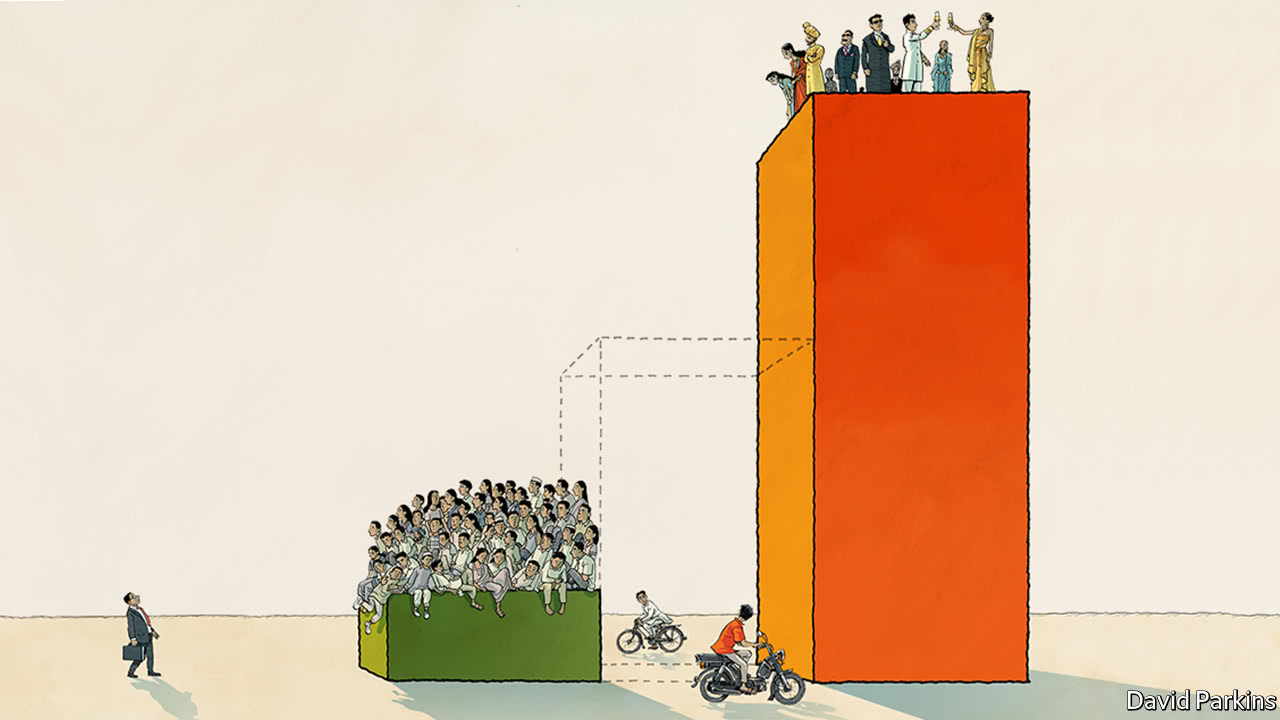

India’s missing middleIndia has a hole where its middle class should be

That should worry both government and companies

AFTER China, where next? Over the past two decades, the world’s most populous country has become the market qua non of just about every global company seeking growth. As its economy slows, businesses are looking for the next set of consumers to keep the tills ringing.

AFTER China, where next? Over the past two decades, the world’s most populous country has become the market qua non of just about every global company seeking growth. As its economy slows, businesses are looking for the next set of consumers to keep the tills ringing.To many, India feels like the heir apparent. Its population will soon overtake its Asian rival’s. It occasionally grows at the kind of pace that propelled China to the status of economic superpower. And its middle class is thought by many to be in the early stages of the journey to prosperity that created hundreds of millions of Chinese consumers. Exuberant management consultants speak of a 300m-400m horde of potential frapuccino-sippers, Fiesta-drivers and globe-trotters. Rare is the chief executive who, upon visiting India, does not proclaim it as central to his or her plans. Some of that may be a diplomatic dose of flattery; much of it, from firms such as IKEA, SoftBank, Amazon and Starbucks, is sincerely meant.

Hold your elephants. The Indian middle class conjured up by the marketers and consultants scarcely exists. Firms peddling anything much beyond soap, matches and phone-credit are targeting a minuscule slice of the population (see article). The top 1% of Indian adults, a rich enclave of 8m inhabitants making at least $20,000 a year, equates to roughly Hong Kong in terms of population and average income. The next 9% is akin to central Europe, in the middle of the global wealth pack. The next 40% of India’s population neatly mirrors its combined South Asian poor neighbours, Bangladesh and Pakistan. The remaining half-billion or so are on a par with the most destitute bits of Africa. To be sure, global companies take the markets of central Europe seriously. Plenty of fortunes have been made there. But they are no China.

Centre parting

Worse, the chances of India developing a middle class to match the Middle Kingdom’s are being throttled by growing inequality. The top 1% of earners pocketed nearly a third of all the extra income generated by economic growth between 1980 and 2014, according to new research from economists including Thomas Piketty. The well-off are ten times richer now than in 1980; those at the median have not even doubled their income. India has done a good job at getting those earning below $2 a day (at purchasing-power parity) to $3, but it has not matched other countries’ records in getting those on $3 a day to earning $5, those at $5 a day to $10, and so on. Middle earners in countries at India’s stage of development usually take more of the gains from growth. Eight in ten Indians cite inequality as a big problem, on a par with corruption.

The reasons for this failure are not mysterious. Decades of statist intervention meant that when a measure of liberalisation came in the early 1990s, only a few were able to benefit. The workforce is woefully unproductive—no surprise given the abysmal state of India’s education system, which churns out millions of adults equipped only for menial work. Its graduates go on to toil in small or micro-enterprises, operating informally; these “employ” 93% of all Indians. The great swell of middle-class jobs that China created as it became the workshop to the world is not to be found in India, because turning small businesses into productive large ones is made nigh-on impossible by bureaucracy. The fact that barely a quarter of women work—a share that has seen a precipitous decline in the past decade—only makes matters worse.

Good policy can do an enormous amount to improve prospects. However, hope should be tempered by realism. India is blessed with a deeply entrenched democratic system, but that is no shield against poor decisions. The sudden and brutal “demonetisation” of the economy in 2016 was meant to target fat cats, but ended up hurting everybody. And the path to prosperity walked by China, where manufacturing produced the jobs that pushed up incomes, is narrowing as automation limits opportunities for factory work.

All of which means that companies need to deal with the India that exists today rather than the one they wish to emerge. A strategy of waiting for Indians to develop a taste for products that the global middle class indulges in—cars as income per head crosses one threshold, foreign holidays when it crosses the next—may lead to decades of frustration. Only 3% of Indians have ever been on an aeroplane; only one in 45 owns a car or lorry. If nearly 300m Indians count as “middle class”, as HSBC has proclaimed, some of them make around $3 a day.

Big market, smaller opportunities

Companies would do better to “Indianise” their business by, for example, peddling wares using regional languages preferred by hundreds of millions of Indians. Pricing matters. Services proffered at the same price in India as Indiana will appeal to mere millions, not a billion. Even for someone in the top 10% of Indian earners, an annual Netflix subscription can cost over a week’s income; the equivalent in America would be around $3,000. Apple ads may plaster Mumbai, Delhi and Bangalore, but for only one in ten Indians would the latest iPhone represent less than half a year’s salary. The biggest consumer hits in India have been goods and services that offer stonking value: scooters and mobile telephony have grown fast, but only after prices tumbled.

The sharpest businesses work out which “enablers” will allow Indians to gain access to new goods. Electrification drives demand for fridges. Cheap mobile data (India is in the midst of a data-price war that has hugely benefited consumers) are a boon to streaming services. Logistics networks put together by e-commerce giants are for the first time making it possible for a consumer in a third-tier city to buy global fashion brands. A surge in consumer financing has put desirable baubles within reach of more Indians.

Insofar as it is the job of politicians to create a consumer class, successive Indian governments have largely failed. Businesses hoping the Indian middle class will provide their next spurt of growth should be under no illusion. Companies will have to work very hard to turn potential into profits.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 13, 2018 at 7:45pm

-

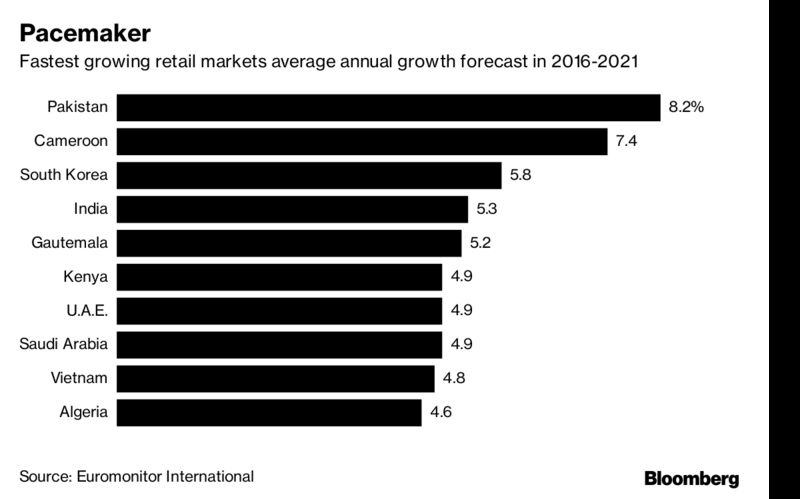

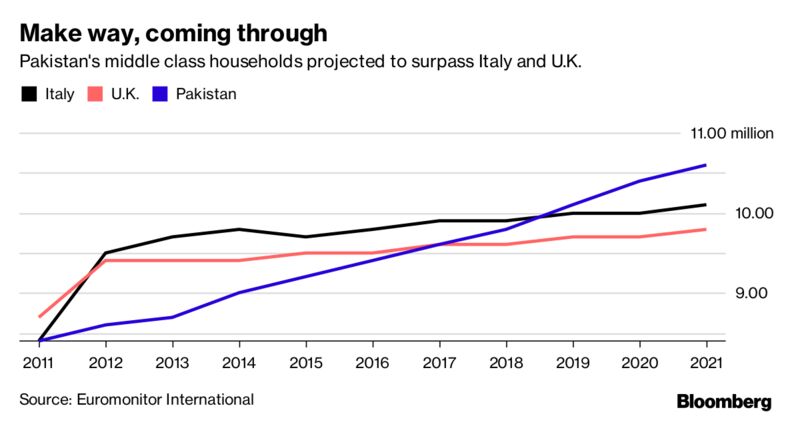

135 Million Millennials Drive World's Fastest Retail Market

Middle class expected to surpass U.K., Italy over 2016-21ByFaseeh MangiSeptember 28, 2017, 1:00 PM PDTFrom- Nearly two-thirds of Pakistan population under 30 years old

- Pakistan’s retail stores forecast to grow by 50% in 5 years

Pakistan’s burgeoning youth and their freewheeling attitude toward rising incomes have turned the nation into the world's fastest growing retail market.

The market is predicted to expand 8.2 percent per annum through 2016-2021 as disposable income has doubled since 2010, according to research group Euromonitor International. The size of the middle class is estimated to surpass that of the U.K. and Italy in the forecast period, it said.

Pakistan's improving security environment, economic expansion at near 5 percent and cheap consumer prices are driving shoppers to spend up big. Almost two-thirds of the nation's 207.8 million people are aged under 30, according to the Jinnah Institute, an Islamabad-based think tank.

“We have a new millennial shopper at hand. They don’t mind spending to have the kind of lifestyle they would like,” said Shabori Das, senior research analyst at Euromonitor. “It’s not like the Baby Boomer generation where savings for the future generation was important.”

Pakistan is bucking the trend in the U.S. -- where stores are closing at a record pace as e-commerce undermines bricks-and-mortar. It's also attracting foreign operators: Turkish home appliance maker Arcelik AS and Dutch dairy giant Royal FrieslandCampina NV entered the market last year via acquisitions. Meanwhile, Hyundai Motor Co., Kia Motors Corp. and Renault SA are all building plants in the South Asian nation.

Pakistan’s retail stores are expected to increase by 50 percent to 1 million outlets in the five years through 2021, Euromonitor said. Its three biggest malls, Lucky One in Karachi and Packages Mall and Emporium Mall in Lahore, opened in the past two years.

Pakistan is mirroring what India went through about four years ago. Both countries have young populations with more income and less inclination toward saving which is a distinct difference to what retailers elsewhere are dealing with, said Das.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-28/135-million-mill...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 14, 2018 at 8:12am

-

Pakistan is ranked third, with growth expected to reach 5.3% in 2017 and 5.6% in 2018, partly as a result of ongoing investment in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/dominicdudley/2017/10/11/fastest-slowe...

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10160135258970227&set=a...

Comment

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Barrick Gold CEO "Super-Excited" About Reko Diq Copper-Gold Mine Development in Pakistan

Barrick Gold CEO Mark Bristow says he’s “super excited” about the company’s Reko Diq copper-gold development in Pakistan. Speaking about the Pakistani mining project at a conference in the US State of Colorado, the South Africa-born Bristow said “This is like the early days in Chile, the Escondida discoveries and so on”, according to Mining.com, a leading industry publication. "It has enormous…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on November 19, 2024 at 9:00am

What Can Pakistan Do to Cut Toxic Smog in Lahore?

Citizens of Lahore have been choking from dangerous levels of toxic smog for weeks now. Schools have been closed and outdoor activities, including travel and transport, severely curtailed to reduce the burden on the healthcare system. Although toxic levels of smog have been happening at this time of the year for more than a decade, this year appears to be particularly bad with hundreds of people hospitalized to treat breathing problems. Millions of Lahoris have seen their city's air quality…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on November 14, 2024 at 10:30am — 1 Comment

© 2024 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network