PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

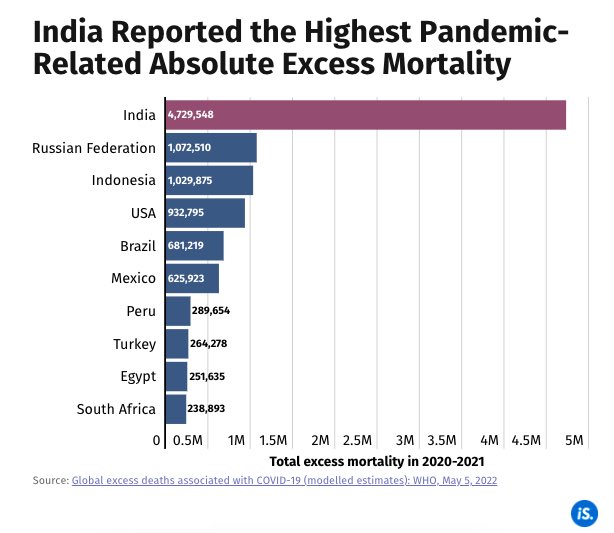

WHO: India's 4.7 Million Excess Deaths Account For Nearly One-Third of the Global COVID Death Toll

The World Health Organization estimates that India had 4.730 million COVID19-related deaths in 2020-21, nearly a third of 15 million global excess deaths attributed to the pandemic. India is followed by Russia with 1.073 million deaths and Indonesia with 1.03 million deaths. The United States with 933,795 deaths and Brazil with 681,219 deaths round out the top 5 countries that suffered the heaviest losses of life believed to be related to the pandemic. Mexico (625,923 deaths), Peru (289,654 deaths), Turkey (264,279 deaths) Egypt (251,635 deaths) and South Africa (238,893 deaths) are ranked number 6 through 10 in the world for excess deaths in 2020-21 period. Although Pakistan too had 8 times the official figure, it still does not figure in WHO's top 10 list for total number of COVID deaths.

|

| Total Excess Deaths Recorded During the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020-2... |

Excess deaths measure how many more people died than expected compared with previous years. Although it is difficult to say with certainty how many of these deaths were due to Covid, they can be considered a measure of the scale and toll of the pandemic, according to the BBC.

Although the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi disputes the WHO estimates, the scenes of desperation and death all over India, including the streets of major cities during the pandemic, offer significant anecdotal evidence to support the WHO claim. Although Pakistan too had 8 times the official figure, it still does not figure in WHO's top 10 list for total number of COVID deaths.

|

| List of Countries with excess deaths during COVID19 pandemic. Sourc... |

Prime Minister Modi's mishandling of the COVID19 pandemic has left a lasting effect on India's economy. Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha (ABPS), the top decision-making body of India's Hindu right-wing RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh), says that “the young generation is suffering from unemployment and the pandemic has made things even grim... We cannot turn a blind eye to unemployment. It is a crisis and it needs to be addressed.” The RSS was apparently reacting to the falling labor participation rate in India relative to Pakistan and the global averages. The RSS leadership wants the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi to focus on helping small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) to create jobs. RSS likes Modi government's ‘Make in India’ initiative “but it needs to be sharpened even more and get more investment.” The resolution is titled, ‘The need to promote work opportunities to make Bharat self-reliant’. The solution offered by ABPS resolution: Take agro-based local initiatives to promote rural areas and create jobs, according to Ram Madhav, a member of the RSS executive committee.

|

| Falling Employment in India. Source: CMIE |

India's labor participation rate (LPR) fell to 39.5% in March 2022, as reported by the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). It dropped below the 39.9% participation rate recorded in February. It is also lower than during the second wave of Covid-19 in April-June 2021. The lowest the labor participation rate had fallen to in the second wave was in June 2021 when it fell to 39.6%. The average LPR during April-June 2021 was 40%. March 2022, with no Covid-19 wave and with much lesser restrictions on mobility, has reported a worse LPR of 39.5%.

|

| Labor Participation Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: ILO/World ... |

In spite of the headline GDP growth figures highlighted by the Indian and world media, the fact is that it has been jobless growth. The labor participation rate (LPR) in India has been falling for more than a decade. The LPR in India has been below Pakistan's for several years, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

|

| Indian Employment Trends By Sector. Source: CMIE Via Business Standard |

Construction and manufacturing sectors in India have been shedding jobs while the number of people working in agriculture has been rising, according to CMIE. Job losses have caused a hunger crisis in India which now ranks 94th among 107 nations ranked by World Hunger Index in 2020. Other South Asians have fared better: Pakistan (88), Nepal (73), Bangladesh (75), Sri Lanka (64) and Myanmar (78) – and only Afghanistan has fared worse at 99th place. The COVID19 pandemic has worsened India's hunger and malnutrition. Tens of thousands of Indian children were forced to go to sleep on an empty stomach as the daily wage workers lost their livelihood and Prime Minister Narendra Modi imposed one of the strictest lockdowns in the South Asian nation. Pakistan's former Prime Minister Imran Khan opted for "smart lockdown" that reduced the impact on daily wage earners. China, the place where COVID19 virus first emerged, is among 17 countries with the lowest level of hunger.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan Reduced Poverty & Grew Economy During COVID Pandemic

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid1...

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Cou...

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade De...

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 12, 2022 at 9:04pm

-

The Indian economy is being rewired. The opportunity is immense And so are the stakes

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2022/05/13/the-indian-economy-is-...

Who deserves the credit? Chance has played a big role: India did not create the Sino-American split or the cloud, but benefits from both. So has the steady accumulation of piecemeal reform over many governments. The digital-identity scheme and new national tax system were dreamed up a decade or more ago.

Mr Modi’s government has also got a lot right. It has backed the tech stack and direct welfare, and persevered with the painful task of shrinking the informal economy. It has found pragmatic fixes. Central-government purchases of solar power have kick-started renewables. Financial reforms have made it easier to float young firms and bankrupt bad ones. Mr Modi’s electoral prowess provides economic continuity. Even the opposition expects him to be in power well after the election in 2024.

The danger is that over the next decade this dominance hardens into autocracy. One risk is the bjp’s abhorrent hostility towards Muslims, which it uses to rally its political base. Companies tend to shrug this off, judging that Mr Modi can keep tensions under control and that capital flight will be limited. Yet violence and deteriorating human rights could lead to stigma that impairs India’s access to Western markets. The bjp’s desire for religious and linguistic conformity in a huge, diverse country could be destabilising. Were the party to impose Hindi as the national language, secessionist pressures would grow in some wealthy states that pay much of the taxes.

The quality of decision-making could also deteriorate. Prickly and vindictive, the government has co-opted the bureaucracy to bully the press and the courts. A botched decision to abolish bank notes in 2016 showed Mr Modi’s impulsive side. A strongman lacking checks and balances can eventually endanger not just demo cracy, but also the economy: think of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, whose bizarre views on inflation have caused a currency crisis. And, given the bjp’s ambivalence towards foreign capital, the campaign for national renewal risks regressing into protectionism. The party loves blank cheques from Silicon Valley but is wary of foreign firms competing in India. Today’s targeted subsidies could degenerate into autarky and cronyism—the tendencies that have long held India back.

Seizing the moment

For India to grow at 7% or 8% for years to come would be momentous. It would lift huge numbers of people out of poverty. It would generate a vast new market and manufacturing base for global business, and it would change the global balance of power by creating a bigger counterweight to China in Asia. Fate, inheritance and pragmatic decisions have created a new opportunity in the next decade. It is India’s and Mr Modi’s to squander. ■

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 14, 2022 at 7:19am

-

Rajeev Matta

@RajeevMatta

India’s total debt in March 2014 was 53 lac crores. In March 2023 it will be 153 lac crores. He has added 100 lac crore in 8 years.

India’s debt to GDP ratio was 73.95% in Dec 20.

(1/n)

https://twitter.com/RajeevMatta/status/1525346057122885632?s=20&...

--------

Rajeev Matta

@RajeevMatta

Foreign reserves are under 600 billion dollars. The trade deficit in March 22 alone was 18.51 billion when we exported the most (an increase of 19.76%); the import too that month increased by 24.21% (they don’t highlight that).

(2/n)

------------

Rajeev Matta

@RajeevMatta

Besides paying for the trade deficit, the foreign reserves need to provide for 256 billion dollars of debt repayment by Sept 22. Imagine, with imports getting costlier where we will be then.

(3/n)

-------------

Rajeev Matta

@RajeevMatta

Indian banks, specially the govt ones are making merry. In FY 21, they wrote off loans worth Rs 2.02 lac crore and since 2014, a whopping 10.7 lac crores. 75% of this is by public sector banks. We all know who all borrowed and scooted or not paying back.

(4/n)

-------------

Rajeev Matta

@RajeevMatta

Finally, the GDP. We were going well at 8.26% in March '16 after which he punctured the tyres of the running car. Remember demonetization? We came down to 6.80 in 17; 6.53 in 18; 4.04 in 19 & -7.96 in 20. Who says pandemic and world economy are responsible for our halt?

(n/n)

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 21, 2022 at 8:59pm

-

Research article

Open Access

Published: 29 May 2020

A comparison of the Indian diet with the EAT-Lancet reference diet

Manika Sharma, Avinash Kishore, Devesh Roy & Kuhu Joshi

https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-0...

The average calorie intake/person/day in both rural (2214 kcal) and urban (2169 kcal) India is less than the reference diet (Table 1). In both rural and urban areas, people in rich households (top deciles of monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE)) consume more than 3000 kcal/day i.e. 20% more than the reference diet. Their calorie intake/person/day is almost twice as high as their poorest counterparts (households in the bottom MPCE deciles) who consume only 1645 kcals/person/day (Table 1).

-------

The average daily calorie consumption in India is below the recommended 2503 kcal/capita/day across all groups compared, except for the richest 5% of the population. Calorie share of whole grains is significantly higher than the EAT-Lancet recommendations while those of fruits, vegetables, legumes, meat, fish and eggs are significantly lower. The share of calories from protein sources is only 6–8% in India compared to 29% in the reference diet. The imbalance is highest for the households in the lowest decile of consumption expenditure, but even the richest households in India do not consume adequate amounts of fruits, vegetables and non-cereal proteins in their diets. An average Indian household consumes more calories from processed foods than fruits.

------------------

The EAT-Lancet reference diet is made up of 8 food groups - whole grains, tubers and starchy vegetables, fruits, other vegetables, dairy foods, protein sources, added fats, and added sugars. Caloric intake (kcal/day) limits for each food group are given and add up to a 2500 kcal daily diet [7]. We compare the proportional calorie (daily per capita) shares of the food groups in the reference diet with similar food groups in Indian Diets.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 21, 2022 at 9:00pm

-

Our total consumption of wheat and atta is about 125kg per capita per year. Our per person per day calorie intake has risen from about 2,078 in 1949-50 to 2,400 in 2001-02 and 2,580 in 2020-21

By Riaz Riazuddin former deputy governor of the State Bank of Pakistan.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1659441/consumption-habits-inflation

As households move to upper-income brackets, the share of spending on food consumption falls. This is known as Engel’s law. Empirical proof of this relationship is visible in the falling share of food from about 48pc in 2001-02 for the average household. This is an obvious indication that the real incomes of households have risen steadily since then, and inflation has not eaten up the entire rise in nominal incomes. Inflation seldom outpaces the rise in nominal incomes.

Coming back to eating habits, our main food spending is on milk. Of the total spending on food, about 25pc was spent on milk (fresh, packed and dry) in 2018-19, up from nearly 17pc in 2001-01. This is a good sign as milk is the most nourishing of all food items. This behaviour (largest spending on milk) holds worldwide. The direct consumption of milk by our households was about seven kilograms per month, or 84kg per year. Total milk consumption per capita is much higher because we also eat ice cream, halwa, jalebi, gulab jamun and whatnot bought from the market. The milk used in them is consumed indirectly. Our total per person per year consumption of milk was 168kg in 2018-19. This has risen from about 150kg in 2000-01. It was 107kg in 1949-50 showing considerable improvement since then.

Since milk is the single largest contributor in expenditure, its contribution to inflation should be very high. Thanks to milk price behaviour, it is seldom in the news as opposed to sugar and wheat, whose price trend, besides hurting the poor is also exploited for gaining political mileage. According to PBS, milk prices have risen from Rs82.50 per litre in October 2018 to Rs104.32 in October 2021. This is a three-year rise of 26.4pc, or per annum rise of 8.1pc. Another blessing related to milk is that the year-to-year variation in its prices is much lower than that of other food items. The three-year rise in CPI is about 30pc, or an average of 9.7pc per year till last month. Clearly, milk prices have contributed to containing inflation to a single digit during this period.

Next to milk is wheat and atta which constitute about 11.2pc of the monthly food expenditure — less than half of milk. Wheat and atta are our staple food and their direct consumption by the average household is 7kg per capita (84kg per capita per year). As we also eat naan from the tandoors, bread from bakeries etc, our indirect consumption of wheat and atta is 41kg per capita. Our total consumption of wheat and atta is about 125kg per capita per year. Our per person per day calorie intake has risen from about 2,078 in 1949-50 to 2,400 in 2001-02 and 2,580 in 2020-21. The per capita per day protein intake in grams increased from 63 to 67 to about 75 during these years. Does this indicate better health? To answer this, let us look at how we devour ghee and sugar. Also remember that each person requires a minimum of 2,100 calories and 60g of protein per day.

Undoubtedly, ghee, cooking oil and sugar have a special place in our culture. We are familiar with Urdu idioms mentioning ghee and shakkar. Two relate to our eating habits. We greet good news by saying ‘Aap kay munh may ghee shakkar’, which literally means that may your mouth be filled with ghee and sugar. We envy the fortune of others by saying ‘Panchon oonglian ghee mei’ (all five fingers immersed in ghee, or having the best of both worlds). These sayings reflect not only our eating trends, but also the inflation burden of the rising prices of these three items — ghee, cooking oil and sugar. Recall any wedding dinner. Ghee is floating in our plates.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 30, 2022 at 7:56am

-

#India taught the world the art of collecting #data. Now the country is staring at a credibility crisis with data - from #Covid deaths to #jobs to #GDP. The Economist recently warned that the country's "statistical infrastructure is crumbling". #Modi #BJP https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-61870699

Indian data is staring at a credibility crisis with official numbers on a range of subjects - from Covid deaths to jobs - being questioned by independent experts. But not too long ago, the country was seen as a world leader in data collection, writes author and historian Nikhil Menon.

Soon after India became independent from British rule, the country took inspiration from the Soviet Union to organise its economy - through centralised five-year plans. This made it imperative for policymakers to have access to accurate, granular information about India's economy.

Here, India faced a problem - as its first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru put it, "we have no data", because of which "we function largely in the dark". Setting up a vast data infrastructure was meant to turn on the lights.

Perhaps the most transformative of the changes introduced was the National Sample Survey, which was established in 1950. It was intended to be a series of sprawling, nationwide surveys that captured information on all aspects of the economic life of citizens.

The idea behind this was that since it would be impossible (or prohibitively expensive) to collect statistics from every household across the nation, it was better to develop a robust and representative sample so that the whole could be calculated from a small fraction.

It was, according to an assessment published by the Hindustan Times newspaper in 1953, "the biggest and most comprehensive sampling inquiry ever undertaken in any country in the world".

-----------

But today, Indian data appears to be in crisis. As the world surges into the era of "big data", India risks being left behind. The Economist recently sounded the alarm, warning that the country's "statistical infrastructure is crumbling". Official figures on issues ranging from Covid mortality to education to poverty are all increasingly distrusted by independent observers and experts - which has alarming implications for policymaking and government accountability.

What makes this especially unfortunate is that India was once a trailblazer in this field. The country would do well to take pride in that inheritance and restore its lost lustre.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 16, 2022 at 11:13am

-

World #SnakeDay: #India is the #Snakebite Capital of the World with one million reported snakebites every year that kill ~60,000 and leave 1.5 lakh to 2 lakh #Indians permanently disabled. There's deteriorating quality, rising costs of antivenom. #disease https://weather.com/en-IN/india/biodiversity/news/2022-07-16-world-...

Poor waste management practices in our cities lead to a thriving rodent population, which in turn leads to a thriving population of snakes, albeit those of just commensal species such as cobras, rat snakes, Russell’s vipers and a few others. Still, the urban residents have little to fear when it comes to snakebites.

The story in rural India is vastly different — akin to two diametrically opposite ‘Indias’ within the same geographic boundary. Our country leads the world in snakebite figures, deaths from snakebite, and even cases of loss of life function.

Now, on the occasion of World Snake Day — observed annually on July 16 to increase awareness about the different species of snake all around the world — we attempt to understand the ground reality of human-snake conflict in India.

India records over 10 lakh snakebites every single year, which kill ~60,000 individuals and leave another 1.5 lakh to 2 lakh people with permanent disabilities. Studies have demonstrated that 94% of the victims are farmers, most of which belong to the most economically productive age groups.

These are staggering figures for a disease that the World Health Organisation (WHO) rightly calls a ‘Neglected Tropical Disease’. However, they are only an unfortunate fraction when compared to the number of snakes that are cruelly and brutally killed in conflict every day across the country.

One cannot help but wonder how India, one of the first countries in the world to develop antivenom over a century ago, remains frozen in time when it comes to safeguarding its citizens from snakebite. A myriad of problems surround the issue of human-snake conflict, and very few have attempted to address it, unlike the conflicts with mega-fauna such as tigers, elephants, bears and others.

Challenges that coil the human-snake conflict in India

The complexity of snakebite begins with the very fact that India, as a tropical country, is blessed with a diversity of snakes rivalled by few others. Among more than 300 species of snakes found in the country, nearly 50 are venomous, of which 18-20 are medically significant — meaning they can cause loss of life or morbidity in their victims if untreated.

Despite these many medically significant species, the lone antivenom available in India only targets the four most commonly found venomous species. This effectively ignores those parts of the country where none of these four species are found. Further, for nearly a decade now, it has been common knowledge that the venom of snakes, even within the same species, varies by region significantly enough to render the antivenom ineffective in several places.

Snake venom, produced at the lone source in the country, has been severely critiqued for its deteriorating quality and increasing costs by the antivenom manufacturers. In turn, herpetologists and venom research scientists have long been urging the pharmaceuticals to upgrade their own processes for the manufacture of antivenom, which will need significantly lower quantities of venom and at least addresses the issue of costs of venom.

Beyond all of these issues, the major hurdle at the hospital stage for the victim, is the lack of availability of antivenom, and the fact that snakebite is a medico-legal case which hoists far more bureaucratic hoops for a victim and their family to jump through. If one were to bypass these hurdles still, they are often faced with a medical fraternity that is so poorly equipped to treat snakebites that victims are often shuttled between hospitals, only for several to succumb in transit.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 22, 2022 at 8:20am

-

PM Modi: The Joke Indians are Not Allowed to Crack

4 April 2022, by THOMAS Rosamma

https://www.ritimo.org/PM-Modi-The-Joke-Indians-are-Not-Allowed-to-...

Parul Khakhar, a poet from Gujarat, posted a poem on Facebook in May, expressing her anguish at the sight of bodies flowing down the Ganges at the height of the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic. ‘Shav vahini Ganga’ – Ganges the Carrier of Corpses – was read widely, translated into several languages and shared on social media. The state government’s literary mouthpiece came down heavily on the poet, claiming it was “misuse of a poem for anarchy”.

Ganges, the Carrier of Corpses

Translated by Salil Tripathi

Don’t worry, be happy, in one voice speak the corpses

O King, in your Ram-Rajya, we see bodies flow in the Ganges

O King, the woods are ashes,

No spots remain at crematoria,

O King, there are no carers,

Nor any pall-bearers,

No mourners left

And we are bereft

With our wordless dirges of dysphoria

Libitina enters every home where she dances and then prances,

O King, in your Ram-Rajya, our bodies flow in the Ganges

O King, the melting chimney quivers, the virus has us shaken

O King, our bangles shatter, our heaving chest lies broken

The city burns as he fiddles, Billa-Ranga thrust their lances,

O King, in your Ram-Rajya, I see bodies flow in the Ganges

O King, your attire sparkles as you shine and glow and blaze

O King, this entire city has at last seen your real face

Show your guts, no ifs and buts,

Come out and shout and say it loud,

“The naked King is lame and weak”

Show me you are no longer meek,

Flames rise high and reach the sky, the furious city rages;

O King, in your Ram-Rajya, do you see bodies flow in the Ganges?

https://www.ritimo.org/PM-Modi-The-Joke-Indians-are-Not-Allowed-to-...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 22, 2022 at 12:23pm

-

From Times of India:

The decline in India’s rankings on a number of global opinion-based indices are due to "cherry-picking of certain media reports" and are primarily based on the opinions of a group of unknown “experts”, a recent study has concluded.

A new working paper titled "Why India does poorly on global perception indices" found that while such indices cannot be ignored as "mere opinions" since they feed into World Bank’s World Governance Indicators (WGI), there needs to be a closer inspection on the methodology used to arrive at the data.

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/indias-declining-rank-in-...

The findings were published by Sanjeev Sanyal, member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister and Aakanksha Arora, deputy director of (EAC to PM).

In the report, the authors conducted a case study of three o ..

In the report, the authors conducted a case study of three

opinion-based indices: Freedom in the World index, EIU

Democracy index and Variety of Democracy.

They drew four broad conclusions from the study:

1) Lack of transparency: The indices were primarily based on

the opinions of a tiny group of unknown “experts”.

2) Subjectivity: The questions used were subjective and

worded in a way that is impossible to answer objectively

even for a country.

3) Omission of important questions: Key questions which

are pertinent to a measure of democracy, like “Is the head of

state democratically elected?”, were not asked.

4) Ambiguous questions: Certain questions used by these

indices were not an appropriate measure of democracy

across all countries.

Here's a look at the three indices examined by the study:

Freedom in the World Index

India’s score on the US-based Freedom in the World Index —

an annual global report on political rights and civil liberties

— has consistently declined post 2018.

It's score on civil liberties was flat at 42 till 2018 but dropped

sharply to 33 by 2022. It's political rights score dropped from

35 to 33. Thus, India’s total score dropped to 66 which places

India in the “partially free” category – the same status it had

during the Emergency.

The study found that only two previous instances where

India was considered as Partially Free was during the time of

Emergency and then during 1991-96 which were years of

economic liberalisation.

"Clearly this is arbitrary. What did the years of Emergency,

which was a period of obvious political repression,

suspended elections, official censoring of the press, jailing of

opponents without charge, banned labour strikes etc, have

in common with period of economic liberalisation and of

today," the study asked.

It concluded that the index "cherry-picked" some media

reports and issues to make the judgement.

The authors further found that in Freedom House's latest

report of 2022, India’s score of the Freedom in the World

Index is 66 and it is in category "Partially Free".

"Cross country comparisons point towards the arbitrariness

in the way scoring is done. There are some examples of

countries which have scores higher than India which seem

clearly unusual. Northern Cyprus is considered as a free

territory with a score of 77 (in 2022 report). It is ironical as

North Cyprus is not even recognised by United Nations as a

country. It is recognised only by Turkey," the authors noted.

Economist Intelligence Unit

In the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Democracy Index,

published the research and consulting arm of the firm that

publishes the Economist magazine, India is placed in the

category of “Flawed Democracy”.

Its rank deteriorated sharply from 27 in 2014 to 53 in 2020

and then improved a bit to 46 in 2021. The decline in rank

has been on account of decline in scores primarily in the

categories of civil liberties and political culture.

The authors found that list of questions used to determine

the outcome was "quite subjective", making objective

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 12, 2023 at 10:17am

-

In the absence of real data, India's stats are all being manufactured by BJP to win elections.

Postponing India’s census is terrible for the country

But it may suit Narendra Modi just fine

https://www.economist.com/asia/2023/01/05/postponing-indias-census-...

Narendra Modi often overstates his achievements. For example, the Hindu-nationalist prime minister’s claim that all Indian villages have been electrified on his watch glosses over the definition: only public buildings and 10% of households need a connection for the village to count as such. And three years after Mr Modi declared India “open-defecation free”, millions of villagers are still purging al fresco. An absence of up-to-date census information makes it harder to check such inflated claims. It is also a disaster for the vast array of policymaking reliant on solid population and development data.

----------

Three years ago India’s government was scheduled to pose its citizens a long list of basic but important questions. How many people live in your house? What is it made of? Do you have a toilet? A car? An internet connection? The answers would refresh data from the country’s previous census in 2011, which, given India’s rapid development, were wildly out of date. Because of India’s covid-19 lockdown, however, the questions were never asked.

Almost three years later, and though India has officially left the pandemic behind, there has been no attempt to reschedule the decennial census. It may not happen until after parliamentary elections in 2024, or at all. Opposition politicians and development experts smell a rat.

----------

For a while policymakers can tide themselves over with estimates, but eventually these need to be corrected with accurate numbers. “Right now we’re relying on data from the 2011 census, but we know our results will be off by a lot because things have changed so much since then,” says Pronab Sen, a former chairman of the National Statistical Commission who works on the household-consumption survey. And bad data lead to bad policy. A study in 2020 estimated that some 100m people may have missed out on food aid to which they were entitled because the distribution system uses decade-old numbers.

Similarly, it is important to know how many children live in an area before building schools and hiring teachers. The educational misfiring caused by the absence of such knowledge is particularly acute in fast-growing cities such as Delhi or Bangalore, says Narayanan Unni, who is advising the government on the census. “We basically don’t know how many people live in these places now, so proper planning for public services is really hard.”

The home ministry, which is in charge of the census, continues to blame its postponement on the pandemic, most recently in response to a parliamentary question on December 13th. It said the delay would continue “until further orders”, giving no time-frame for a resumption of data-gathering. Many statisticians and social scientists are mystified by this explanation: it is over a year since India resumed holding elections and other big political events.

Comment

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Has Pakistan Destroyed India's S-400 Air Defense System at Adampur?

Pakistan claims its air force (PAF) has destroyed India's high-value Russian-made S-400 air defense system (ADS) located at the Indian Air Force (IAF) Adampur air base. India has rejected this claim and posted pictures of Prime Minister Narendra Modi posing in front of its S-400 rocket launchers in Adampur. Meanwhile, there are reports that an Indian S-400 operator, named Rambabu Kumar Singh, was killed at about the time Pakistan claims to have hit it. Pakistan is believed to have targeted…

ContinuePakistan Downs India's French Rafale Fighter Jets in History's Largest Aerial Battle

Pakistan Air Force (PAF) pilots flying Chinese-made J10C fighter jets shot down at least two Indian Air Force's French-made Rafale jets in history's largest ever aerial battle involving over 100 combat aircraft on both sides, according to multiple media reports. India had 72 warplanes on the attack and Pakistan responded with 42 of its own, according to Pakistani military. The Indian government has not yet acknowledged its losses but senior French and US intelligence officials have …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on May 9, 2025 at 11:00am — 32 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network