PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Top One Percent: Are Hindus the New Jews in America?

Hindu Americans have surpassed Jewish Americans in education and rival them in household incomes. How did immigrants from India, one of the world's poorest countries, join the ranks of the richest people in the United States? How did such a small minority of just 1% become so disproportionately represented in the highest income occupations ranging from top corporate executives and technology entrepreneurs to doctors, lawyers and investment bankers? Indian-American Professor Devesh Kapur, co-author of The Other One Percent: Indians in America, explains it in terms of educational achievement. He says that an Indian-American is at least 9 times more educated than an individual in India. He attributes it to what he calls a process of "triple selection".

Hindu American Household Income:

A 2016 Pew study reported that more than a third of Hindus (36%) and four-in-ten Jews (44%) live in households with incomes of at least $100,000. More recently, the US Census data shows that the median household income of Indian-Americans, vast majority of whom are Hindus, has reached $127,000, the highest among all ethnic groups in America.

Median income of Pakistani-American households is $87.51K, below $97.3K for Asian-Americans but significantly higher than $65.71K for overall population. Median income for Indian-American households $126.7K, the highest in the nation.

|

|

|

Hindu Americans Education:

Indian-Americans, vast majority of whom are Hindu, have the highest educational achievement among the religions in America. More than three-quarters (76%) of them have at least a bachelors's degree. This high achieving population of Indian-American includes very few of India’s most marginalized groups such as Adivasis, Dalits, and Muslims.

By comparison, sixty percent of Pakistani-Americans have at least a bachelor's degree, the second highest percentage among Asian-Americans. The average for Asian-Americans with at least a bachelor's degree is 56%.

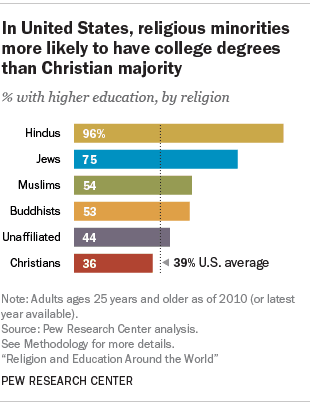

American Hindus are the most highly educated with 96% of them having college degrees, according to Pew Research. 75% of Jews and 54% of American Muslims have college degrees versus the US national average of 39% for all Americans. American Christians trail all other groups with just 36% of them having college degrees. 96% of Hindus and 80% of Muslims in the U.S. are either immigrants or the children of immigrants.

|

| US Educational Attainment By Religion Source: Pew Research |

Jews are the second-best educated in America with 59% of them having college degrees. Then come Buddhists (47%), Muslims (39%) and Christians (25%).

Triple Selection:

Devesh Kapur, a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania and co-author of The Other One Percent: Indians in America (Oxford University Press, 2017), explains the phenomenon of high-achieving Indian-Americans as follows: “What we learned in researching this book is that Indians in America did not resemble any other population anywhere; not the Indian population in India, nor the native population in the United States, nor any other immigrant group from any other nation.”

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Pakistani-Americans: Young, Well-educated and Prosperous

Hindus and Muslim Well-educated in America But Least Educated World...

What's Driving Islamophobia in America?

Pakistani-Americans Largest Foreign-Born Muslim Group in Silicon Va...

Caste Discrimination Among Indian-Americans in Silicon Valley

Islamophobia in America

Silicon Valley Pakistani-Americans

Pakistani-American Leads Silicon Valley's Top Incubator

Silicon Valley Pakistanis Enabling 2nd Machine Revolution

Karachi-born Triple Oscar Winning Graphics Artist

Pakistani-American Ashar Aziz's Fire-eye Goes Public

Two Pakistani-American Silicon Valley Techs Among Top 5 VC Deals

Pakistani-American's Game-Changing Vision

Minorities Are Majority in Silicon Valley

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 3, 2021 at 8:04pm

-

How Indian Americans Came to Love the Spelling Bee

Since 2008, a South Asian American child has been named a champion at every Scripps National Spelling Bee.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/03/style/spelling-bee-south-asian-a...

In 2016 and 2017, Indians accounted for almost 75 percent of all H-1B visa holders in the United States. This “changed the character of the community, in terms of skewing it more professional and more highly educated,” Dr. Mishra said.

Parents were looking for hobbies for their children that prioritized “all kinds of educational attainment,” said Dr. Shankar. Spelling as an extracurricular activity soon began to spread by word of mouth. “They tell their broader ethnic community about it, and they bring each other to these South Asian spelling games, which are really accessible and held in areas where there’s a large concentration of South Asian Americans,” she said.

The hobby is also passed down — within families — to younger siblings and cousins. (“If the older sibling did it, the younger one often follows,” said Dr. Shankar.) That was the case for the 2016 Scripps champion, Nihar Janga, 16, whose passion for spelling was born out of a sibling rivalry going back to age 5. Watching his mother quiz his older sister, Navya, as she was preparing for the bee, Nihar started chiming in, reciting spellings even before Navya could finish.

“I looked up to the fact that my sister was participating in something like this, but I also wanted to be better at it. Eventually, it grew into my own love for spelling and everything it’s taught me,” Nihar said.

An Engine for Success

Navya and Nihar’s family, who live in Austin, Texas, first came across spelling bees through Navya’s bharatanatyam (an Indian classical dance) teacher, who was involved with the nonprofit North South Foundation.The foundation has over 90 chapters, hosts regional and national educational contests in a variety of subject areas, and raises money through these events for disadvantaged students in India. A spelling bee is among the contests run by the organization, and it’s common for top contenders to continue on to Scripps.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 4, 2021 at 6:28pm

-

Pew: Religion and Education Around the World

Large gaps in education levels persist, but all faiths are making gains – particularly among women

Hindus in India, who make up a large majority of the country’s population (and more than 90% of the world’s Hindus), have relatively low levels of educational attainment – a nationwide average of 5.5 years of schooling. While they are more highly educated than Muslims in India (14% of the country’s population), they lag behind Christians (2.5% of India’s population). By contrast, fully 87% of Hindus living in North America hold post-secondary degrees – a higher share than any other major religious group in the region.https://www.pewforum.org/2016/12/13/religion-and-education-around-t...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 4, 2021 at 6:36pm

-

India’s Muslims: An Increasingly Marginalized Population

India’s Muslim communities have faced decades of discrimination, which experts say has worsened under the Hindu nationalist BJP’s government.https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/india-muslims-marginalized-populat...

Summary

Some two hundred million Muslims live in India, making up the predominantly Hindu country’s largest minority group.For decades, Muslim communities have faced discrimination in employment and education and encountered barriers to achieving wealth and political power. They are disproportionately the victims of communal violence.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the ruling party have moved to limit Muslims’ rights, particularly through the Citizenship Amendment Act, which allows fast-tracked citizenship for non-Muslim migrants from nearby countries.

“The longer Hindu nationalists are in power, the greater the change will be to Muslims’ status and the harder it will be to reverse such changes,” says Ashutosh Varshney, an expert on Indian intercommunal conflict at Brown University.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 5, 2021 at 9:30am

-

Pakistani doctors recognize the heroes of pandemic among them | ksdk.com

https://www.ksdk.com/article/news/health/pakistani-physicians-of-st...

T. LOUIS COUNTY, Mo. — The Association of Physicians of Pakistani Descent of North America recognized healthcare workers for being on the front lines during the ongoing pandemic.

"I think there's strength in numbers," said Dr. Tariq Alam, St. Louis Chapter President of APPNA. "One physician alone can't win this fight. We all have to pour in our ideas. Get the best from everyone and get the best solution for our region."

For the 250-plus members, collaborating across healthcare networks in our region was easy, Dr. Alam said. He also says it brought doctors closer to the community.

"We have many who have language barriers, or economic barriers," Dr. Alam said. "Basically being able to reach out to them, I think that is one of our highlights."

Member and St. Louis County Health Director Dr. Faisal Khan said there's not enough praise to go around.

"The only reason we aren't looking at a 3 million or 4 million death count is because of the selfless work and sacrifice of healthcare providers across the country," Dr. Khan said. "We owe them everything."

Khan said the work isn't done yet.

"I am very happy that nearly 35% in the St. Louis region is vaccinated," Dr. Khan said. "I am equally worried that 65% of us are not. We are not out of this yet."

Khan is happy that county leaders support strong health guidelines until we cross the finish line. He said it's going to take more community action before things return to normal.

"It depends entirely on how the virus behaves, on the number of people getting vaccinated and the spread of disease in smaller communities in high-risk groups," Khan said.

Until then, doctors say mask up and get the vaccine or encourage others to do so.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 9, 2021 at 7:05pm

-

Zaila Avant-garde: #African-#American Teenager makes history at #US #spellingbee. it’s the first time since 2008 that at least one champion or co-champion of the Scripps National Spelling Bee is not of #SouthAsian descent. #Indian-#American - BBC News

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-57773502

A teenage basketball prodigy has become the first African American to win the US Scripps National Spelling Bee.

Zaila Avant-garde, a 14-year-old from New Orleans, Louisiana, cruised to victory with the word "murraya", a type of tropical tree.

To get to that point she had to spell out "querimonious" and "solidungulate".

Despite practising for up to seven hours a day, she describes spelling as a side hobby - Zaila's main focus is on becoming a basketball pro.

She already holds three world records for dribbling multiple balls at once, and has appeared in an advertisement with the NBA megastar Stephen Curry.

Zaila saw off a field of 11 finalists on Thursday to win the title and bagged a first-place prize of $50,000 (£36,000) at the event in Orlando, Florida.

In the final round, she beat 12-year-old Chaitra Thummala of Frisco, Texas.

It was the first time since 2008 that at least one champion or co-champion of the Scripps National Spelling Bee was not of South Asian descent, the Associated Press news agency reports.

Why do Indian-Americans win spelling bee contests?

Zaila had earlier in the evening hesitated over the word nepeta, a herbal mint, but managed to spell it correctly.

"For spelling, I usually try to do about 13,000 words [per day], and that usually takes about seven hours or so," the home-schooled teen told New Orleans paper the Times-Picayune.

"We don't let it go way too overboard, of course. I've got school and basketball to do."

Zaila is the second black girl to win the tournament - Jody-Anne Maxwell, of Jamaica, was crowned champion in 1998 at the age of 12.

In 2019, eight children came joint-first for the first time in the spelling bee's history. The tournament was cancelled last year because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 11, 2021 at 10:46am

-

Virgin Galactic's Sirisha Bandla, an #Indian-#American woman aeronautical engineer, wants more women, people of color in space. Historically, most astronauts have been white, male, and military. #VirginGalactic #SpaceTourism #Branson #Unity22 https://www.newsweek.com/virgin-galactic-sirisha-bandla-women-peopl...

The first time non-white and women astronauts were selected by NASA was in 1978 as the agency looked to add candidates with a wide variety of backgrounds for its then-upcoming Space Shuttle program.

------------------------

Sirisha Bandla is one of five people joining billionaire Richard Branson on board a Virgin Galactic flight to space on Sunday.

The 34-year-old scientist is Virgin Galactic's vice president of government affairs and research, and will be handling a University of Florida research project onboard.

When V.S.S. Unity reaches its maximum 55-miles up, Bandla will become only the second India-born woman and third person of Indian descent to leave Earth's atmosphere. Although there is some debate about the point at which the planet ends and space begins.

The scientist has spoken out about a lack of diversity in the space industries—and space itself—in the months leading up to the flight.

"Women and people of color you don't often see...I don't often see students that look like myself in this industry just yet," Bandla said in a September 2020 interview with Matthew Isakowitz Fellowship, a program helping college students into the commercial spaceflight industry.

Historically, most astronauts have been white, male, and military.

Analysis of NASA's intake from 1959 to 2017 by National Geographic, however, has shown how things are changing at the space agency. It did not look at the emerging private space industry, of which Virgin Galactic is a part.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 26, 2021 at 10:35am

-

#Dalit Scientists Face Barriers in #India's Top #Science Institutes. About 17% of India’s population, Dalits who are officially referred to as “Scheduled Castes” in government records. #caste #Apartheid #Hindutva #Modi #Brahmin https://undark.org/2021/07/26/dalit-scientists-face-barriers-in-ind... via @undarkmag

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1419710594815434757?s=20

Interviews with young Dalit scientists, along with a growing body of academic work, detail the obstacles Dalits still face on their path through scientific training. Those barriers begin early: Just getting into science and engineering education has been a challenging and uncommon choice for Dalit students in the first place, according to Wankhede, the educational sociologist. “Science education is very expensive. Highly inaccessible,” he said. Students pay higher tuition rates for science courses than in other areas, because they are required to take additional classes to do experiments. And to keep up with their coursework, science students often pay for instruction in pricey private academies called coaching institutes, something many Dalit families cannot afford.

For those Dalits who make it into elite scientific institutes, cultural barriers remind them of the caste divide. During his time at IISc, Thomas found that his lower-caste and Dalit sources identified reflections of upper caste culture throughout the institute. Thomas focused on the Carnatic music concerts that Brahmin students organized. Traditionally, Carnatic music, a type of classical music, has long been the domain of Brahmins in southern India. In one instance at IISc, after the singer finished her song, the Brahmin audience continued singing, showing their familiarity with the art form, writes Thomas. But such events alienated researchers who were not Brahmin. One saw Carnatic music as a “symbol of domination” and said he preferred “folk songs and songs of resistance by Dalit reformers.”

“The mindset remains extraordinarily Brahminical in these elite institutions,” said Abha Sur, a historian of science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has written about caste and gender in Indian science. That mindset, she added, tacitly aligns itself with caste hierarchy: “There is implicit devaluation of people that continuously erodes their sense of self.”

---------------------

EVEN AS DALIT researchers like Sonkawade and Kale recount fighting against casteism, many upper-caste researchers describe themselves as caste-blind, or beyond caste — a phenomenon, critics say, that has made it more difficult to address ongoing disparities in top scientific institutions.

In 2012, social anthropologist Renny Thomas joined a chemistry laboratory at the Indian Institute of Sciences to study caste dynamics at the institute, arguably India’s most elite science university. That year, he interviewed 80 researchers, and later observed a cultural festival celebrated at the institute. Again and again, Thomas found, Brahmin researchers denied that caste existed in their lives or on the campus. “Caste!?? Oh, Please! I have nothing to do with caste,” one molecular biologist from a Brahmin family told Thomas, according to a paper he published last year. “It never registered in my mind.”

Such claims aren’t limited to academic science. In a 2013 paper, University of Delhi sociologist Satish Deshpande argued that for many upper-caste Indians, caste is “a ladder that can now be safely kicked away,” but only after they convert those high-caste privileges into other forms of status, such as “property, higher educational credentials, and strongholds in lucrative professions.” Many Dalits, Kale said, would also like to forget their caste. But upper-caste people, he added, “don’t let us.”

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 31, 2021 at 7:14am

-

Rich #Indians leaving #India: Some of the most sought-after residential visas are for countries like #US, #UK, #Portugal, and #Greece. These jurisdictions provide various investment options, and attractive returns on real estate. #Modi #BJP #economy #COVID https://www.business-standard.com/article/markets/more-more-rich-le...

Wealthy Indians are increasingly domiciling their families and businesses overseas for better investment opportunities, wealth preservation, lifestyle, and health care.

Some of the most sought-after residential visas are for countries, such as the US, the UK, Portugal, and Greece. These jurisdictions provide various investment options, as well as attractive returns on real estate. “After the lull in immigration programmes during the initial phases of the pandemic, we are now seeing more and more families evaluating alternative residencies and citizenship programmes,” said ...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 1, 2021 at 7:27am

-

Americans: Results From the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey

SUMITRA BADRINATHAN, DEVESH KAPUR, JONATHAN KAY, MILAN VAISHNAV

https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/06/09/social-realities-of-indian...

U.S. Census data affirm that Indian Americans enjoy a standard of living that is roughly double that of the median American household, underpinned by substantially greater educational attainment—the share of Indian Americans with at least a bachelor’s degree is twice the national average.4 However, these aggregate figures mask severe inequalities within the community. Although overall levels of poverty are lower than the American average,5 there are concentrated pockets of deprivation, especially among the large number of unauthorized immigrants born in India and residing in the United States.6

Additionally, a narrow focus on demographics such as income, wealth, education, and professional success can obscure important (and sometimes uncomfortable) social truths. What are the social realities and lived experiences of Indian Americans? How does this group perceive itself, and how does it believe others perceive it? To what extent does the community exhibit signs of shared solidarity, and are there signs of division as the group grows in number and diversity? These are some questions this paper attempts to address.

While the social realities of Indian Americans are often glossed over, recent events have brought them to the fore. In 2020, California’s Department of Fair Employment and Housing filed a lawsuit against U.S.-based technology company Cisco Systems after an employee from one of India’s historically marginalized caste communities (“Dalits”) alleged that some of his upper caste Indian American colleagues discriminated against him on the basis of his caste identity.7 The suit, and subsequent media melee, triggered a wave of wrenching testimonials about the entrenched nature of caste—a marker of hierarchy and status associated with Hinduism (as well as other South Asian religions)—within the diaspora community in the United States.8

----------

Thirty percent of non-citizen IAAS respondents possess a green card (or a permanent residency card), which places them on a pathway to gaining U.S. citizenship. Twenty-seven percent are H-1B visa holders, a visa status for high-skilled or specialty workers in the United States that has historically been dominated by the technology sector. On average, an H-1B visa holder reports living in the United States for eight years, although 36 percent of H-1B beneficiaries report spending more than a decade in the country (that is, they arrived before 2010). Eighteen percent of non-citizens reside in the United States on an H-4 visa, a category for immediate family members of H-1B visa holders. Fourteen percent of non-citizens are on F-1, J-1, or M-1 visas—categories of student or scholar visas—while another 5 percent hold an L-1 visa, a designation available to employees of an international company with offices in the United States. A small minority of non-citizen respondents—6 percent—claim some other visa status.

----------

Ten percent of IAAS respondents identify as “South Asian American,” a term which refers to diaspora populations from countries across the region such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Six percent choose no hyphenation at all and identify only as “American” and another 6 percent classify themselves as “Asian American,” an identity category that includes a wide range of diaspora groups from the Asian continent. Two percent of respondents identify as “Other,” indicating that none of the declared options satisfy them, while just 1 percent identify as “Non-resident Indian,” the official appellation used by the Government of India to refer to Indian passport holders living outside of India.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 6, 2021 at 10:22am

-

The Casteism I See in America - The Atlantic

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/11/india-america-cas...

A 2016 study by Equality Labs, an American civil-rights organization focused on caste, found that 41 percent of South-Asian Americans who identify as lower-caste reported facing caste discrimination in U.S. schools and universities, compared with 3 percent of upper-caste respondents. The survey indicated that 67 percent of lower-caste respondents said they had suffered caste discrimination in the workplace, versus 1 percent of upper-caste individuals. (The survey of more than 1,500 people focused on Hindus. Though upper castes hold more power, caste discrimination is more complex than simply being meted out by upper castes against lower castes, Thenmozhi Soundararajan, Equality Labs’s executive director, told me. “In fact,” she said, “it is all castes against all castes.”)

More recently, a September 2020 study by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace found that first-generation Indian immigrants to the U.S. were significantly more likely than U.S.-born respondents to espouse a caste identity. The overwhelming majority of Hindus with a caste identity—more than eight in 10—self-identified as upper-caste, and first-generation immigrants in particular tended to self-segregate, making their communities more and more homogenous in terms of religion and caste. Respondents to the Carnegie survey had varying responses to experiencing different forms of discrimination, depending on whether the discrimination occurred in the U.S. or in India, and who suffered from it. Overall, 73 percent viewed white supremacy as a threat to American democracy, but only 53 percent saw Hindu majoritarianism as a threat to Indian democracy. On the question of affirmative action in university admissions, the data suggest higher levels of support for the policy in the U.S. (54 percent) than India (47 percent).

The anguish caused by casteism is much like that caused by racism, resulting not simply from hateful slurs but from an expansive and intimate system woven into behavior, cultural practice, and economics. On a granular level, upper-caste Hindus do not share utensils or drinking water with those of lower castes, and lighter skin tones are preferred to darker ones. On a systemic level, society self-segregates, with upper castes often congregating in the same neighborhoods; the achievements of upper-caste Hindus come at least partially at the expense of lower-caste communities.

The system dictates that every child inherits their family’s caste, which is indicated by a person’s middle and last name—the name of one’s village and the profession of the family. Caste determines social status and spiritual purity and defines what jobs a person can do and whom they can marry. As outlined in Hindu mythology, men were created unequal by Lord Brahma, the Creator, supreme among the triad of Hindu gods that also includes Lord Shiva, the Destroyer, and Lord Vishnu, the Preserver. From Brahma’s head came the Brahmans—priests and intellectuals. From his arms came kings and warriors; from his thighs, white-collar workers; and from his feet, blue-collar workers. A fifth group, once described as untouchables, was kept outside of the caste system entirely, its place in the social order to clean toilets, sweep streets, and dispose of dead bodies. (The word pariahcomes from the Tamil language and refers to one of the most persecuted and lowest of caste groups, the paṛaiyar, in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Pariah is a global standard for social outcasts, but Tamil-Brahman families, including mine, use it as a term of abuse, and it has come to mean “someone who is despised.”)

The top three groups—Brahmans, warriors, and traders—are the upper castes and can intermarry and dine with one another.

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

IDEAS 2024: Pakistan Defense Industry's New Drones, Missiles and Loitering Munitions

The recently concluded IDEAS 2024, Pakistan's Biennial International Arms Expo in Karachi, featured the latest products offered by Pakistan's defense industry. These new products reflect new capabilities required by the Pakistani military for modern war-fighting to deter external enemies. The event hosted 550 exhibitors, including 340 international defense companies, as well as 350 civilian and military officials from 55 countries.

Pakistani defense manufacturers…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on December 1, 2024 at 5:30pm — 2 Comments

Barrick Gold CEO "Super-Excited" About Reko Diq Copper-Gold Mine Development in Pakistan

Barrick Gold CEO Mark Bristow says he’s “super excited” about the company’s Reko Diq copper-gold development in Pakistan. Speaking about the Pakistani mining project at a conference in the US State of Colorado, the South Africa-born Bristow said “This is like the early days in Chile, the Escondida discoveries and so on”, according to Mining.com, a leading industry publication. "It has enormous…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on November 19, 2024 at 9:00am

© 2024 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network