PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Pew Research: Two-thirds of Hindus Say Only Hindus "Truly Indian"

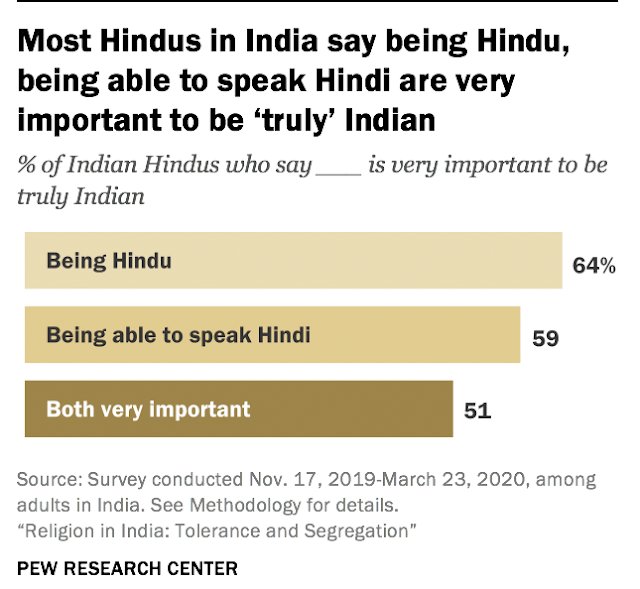

A recent Pew survey in India has found that 64% of Hindus see their religious identity and Indian national identity as closely intertwined. Most Hindus (59%) also link Indian identity with being able to speak Hindi language. The survey was conducted over two years in 2019 and 2020 by Pew Research Center. It included 29,000 Indians.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Hindu Nationalist BJP party's appeal is the greatest among Hindus who closely associate their religious identity and the Hindi language with being “truly Indian.” The Pew survey found that less than half of Indians (46%) favored democracy as best suited to solve the country’s problems. Two percent more (48%) preferred a strong leader.

|

| Most Hindus Link Hindu Religion and Hindi Language With Indian Nati... |

The majority of Hindus see themselves as very different from Muslims (66%), and most Muslims return the sentiment, saying they are very different from Hindus (64%). Most Muslims across the country (65%), along with an identical share of Hindus (65%), see communal violence in India as a very big national problem. Like Hindus, Muslims prefer to live religiously segregated lives – not just when it comes to marriage and friendships, but also in some elements of public life. In particular, three-quarters of Muslims in India (74%) support having access to the existing system of Islamic courts, which handle family disputes (such as inheritance or divorce cases), in addition to the secular court system.

Most Hindus (59%) also link Indian identity with being able to speak Hindi – one of dozens of languages that are widely spoken in India. And these two dimensions of national identity – being able to speak Hindi and being a Hindu – are closely connected. Among Hindus who say it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian, fully 80% also say it is very important to speak Hindi to be truly Indian.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Hindu Nationalist BJP party's appeal is the greatest among Hindus who closely associate their religious identity and the Hindi language with being “truly Indian.” In the 2019 national elections, 60% of Hindu voters who think it is very important to be Hindu and to speak Hindi to be truly Indian cast their vote for the BJP, compared with only a third among Hindu voters who feel less strongly about both these aspects of national identity.Disintegration of India

Dalit Death Shines Light on India's Caste Apartheid

India's Hindu Nationalists Going Global

Rape: A Political Weapon in Modi's India

Trump's Dog Whistle Politics

Funding of Hate Groups, NGOs, Think Tanks: Is Money Free Speech?

Riaz Haq Youtube Channel

PakAlumni: Pakistani Social Network

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 26, 2022 at 9:33am

-

‘A threat to unity’: anger over push to make Hindi national language of India | India | The Guardian

‘A threat to unity’: anger over push to make #Hindi national language of #India. Tensions are rising in India over prime minister Narendra #Modi’s push to make Hindi the country’s dominant language. #BJP #Hindutva | India | The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/dec/25/threat-unity-anger-ov...

Tensions are rising in India over prime minister Narendra Modi’s push to make Hindi the country’s dominant language.

Modi’s Bharatiya Janaya party (BJP) government has been accused of an agenda of “Hindi imposition” and “Hindi imperialism” and non-Hindi speaking states in south and east India have been fighting back.

One morning in November, MV Thangavel, an 85-year-old farmer from the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, stood outside a local political party office and held a banner aloft, addressing Modi. “Modi government, central government, we don’t want Hindi … get rid of Hindi,” it read. Then he doused himself in paraffin and set himself alight. Thangavel did not survive.

“The BJP is trying to destroy other languages by trying to impose Hindi and make it one language on the basis of its ‘One Nation, One everything’ policy,” said MK Stalin, the chief minister of Tamil Nadu, in a recent speech.

In India, one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world, language has long been a contentious issue. But under Modi, there has been a tangible push for Hindi to be the country’s dominant language, be it through an attempt to impose mandatory Hindi in schools across the country to conducting matters of government entirely in the language. Modi’s speeches are given exclusively in Hindi and over 70% of cabinet papers are now prepared in Hindi. “If there is one language that has the ability to string the nation together in unity, it is the Hindi language,” said Amit Shah, the powerful home minister and Modi’s closest ally, in 2019.

According to Ganesh Narayan Devy, one of India’s most renowned linguists who dedicated his life to recording India’s over 700 languages and thousands of dialects, the recent attempts to impose Hindi were both “laughable and dangerous”.

“It’s not one language but the multiplicity of languages that has united India throughout history. India cannot be India unless it accommodates all native languages,” said Devy.

According to the most recent census in 2011, 44% of Indians speak Hindi. However, 53 native languages, some of which are entirely distinct from Hindi and have millions of speakers, are also classed under the banner of Hindi. Removing all the other languages would shrink the number of Hindi speakers to about 27%, meaning almost three-quarters of the country is not fluent.

Devy said being multilingual was at the heart of being Indian. “You will find people use Sanskrit for their prayers, Hindi for films and affairs of the heart, their mother tongue for their families and private thoughts, and English for their careers,” he said. “It’s hard to find a monolingual Indian. That should be celebrated, not threatened.”

‘Our language is who we are’

The debate over Hindi’s prominence has raged since before India’s independence. Though there are more Hindi speakers than those of any other native language in India, they are largely concentrated in the populous, politically powerful states in the north known as the Hindi belt. Hindi traditionally has very little presence in southern states such as Tamil-speaking Tamil Nadu and Malayalam-speaking Kerala, and eastern states such as West Bengal, home to 78 million Bengali speakers.

When the constitution was drawn up in 1949 it was decided that India should have no one national language. Instead 14 languages – a list which eventually grew to 22 – were formally recognised in the constitution, though Hindi and English were declared to be the “official languages” in which matters of national government and administration would be communicated.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 26, 2022 at 9:34am

-

‘A threat to unity’: anger over push to make Hindi national language of India | India | The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/dec/25/threat-unity-anger-ov...

Attempts were made to designate Hindi the single dominant language but were all met with protest, mostly from the south. In the 1960s, after the government declared that Hindi would be the only “official language” and English phased out, there was a violent uprising in Tamil Nadu where several people set themselves on fire and dozens died in the brutal crackdown on the protests. The government backtracked. To this day, only Tamil and English are taught in state schools in Tamil Nadu.

But it was after the election of the BJP government in 2014, whose Hindu nationalist agenda has included a tangible push for the promotion of Hindi, that the issue resurfaced again, and the government was accused of imposing cultural hegemony over non-Hindi-speaking states.

“Under Modi, language has become a heavily politicised issue,” said Papia Sen Gupta, a professor in the Centre for Political Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. “The narrative being projected is that India must be reimagined as Hindu state and that in order to be a true Hindu and a true Indian, you must speak Hindi. They are becoming more and more successful in implementing it.”

The idea of Hindi as India’s national language has its roots in the writings of VD Savarkar, the father of hardline Hindu nationalism and an icon of the BJP, who first articulated the slogan “Hindi, Hindu, Hindustan”, conflating nationalism with both religion and language, a phrase which is still commonly used by the right wing today.

There was such a backlash to the BJP’s attempts to introduce mandatory Hindi in schools nationally that they were later withdrawn. In October, Shah had non-Hindi states up in arms again, this time with a recommendation that that central universities and institutes of national importance should carry out teaching and exams only in Hindi, rather than English. The rule would only apply for institutions in Hindi-speaking states. But as many pointed out, students from across the country attend these schools, including from the south and east where Hindi is not part of the curriculum.

In response to Shah’s recommendation, in Tamil Nadu, MK Stalin tabled a state parliamentary resolution against any “imposition of a dominant language” and alleged that the BJP was attempting to make “Hindi the language that symbolises power”. He is also pushing for Tamil to be designated an official language, equal in status to Hindi. In Kerala and Karnataka, groups and political parties also raised concern over the “Hindi imposition”.

Some have warned of the bloody history that language imposition has triggered in the region. Sri Lanka descended into 26-year civil war after Sinhalese nationalists tried to foist their language on the island’s minority Tamils, and it was the oppression of the Bengali language in east Pakistan that led to the 1971 war and the establishment of Bangladesh.

The BJP government says it is not using Hindi to replace other native languages, but only English, the western language of India’s colonisers. But with English so deeply engrained in the Indian system, used across everything from the courts to the job market, and the proliferation of English seen to give India an advantage in a globalised world, there is little sign of it realistically being phased out in favour of Hindi.

In response to the policies seen to promote Hindi, multiple nationalist language movements have now emerged across India, from Rajasthan to West Bengal. In West Bengal, where the Bengali language is seen as a very fundamental part of people’s cultural identity, there has been a growing Bengali nationalist movement over the past two years.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 26, 2022 at 9:34am

-

‘A threat to unity’: anger over push to make Hindi national language of India | India | The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/dec/25/threat-unity-anger-ov...

In response to the policies seen to promote Hindi, multiple nationalist language movements have now emerged across India, from Rajasthan to West Bengal. In West Bengal, where the Bengali language is seen as a very fundamental part of people’s cultural identity, there has been a growing Bengali nationalist movement over the past two years.

“It’s Hindi imperialism,” said Garga Chatterjee, general secretary of Bangla Pokkho, a Bengali nationalist group established in 2018. “They want to transform India from a union of diverse states to one a nation state, where people who speak Hindi are treated as first-class citizens while we non-Hindi people, including Bengalis, are second-class citizens.”

Chatterjee said that, despite Bengali being the second most spoken language in India, he could not get a copy of the Indian constitution, open a bank account, book a railway ticket or a fill out tax return in his mother tongue.

“They are making Hindi the face of India and this is a direct threat to the unity of India,” he said. “We Bengalis are being talked down to in Hindi but now we are pushing back. Our language is who we are and we will die for it.”

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 13, 2023 at 10:22am

-

Ghanznavi's Destruction of Somnath Was Not a Hindu-Muslim Issue When it HappenedIt was deliberately distorted by the British colonial rulers to divide and conquer India, according to Indian historian Romila Thapar.British distortions of history have since been exploited by Hindu Nationalists to pursue divisive policies.In 1026, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni raided the Hindu temple of Somanatha (Somnath in textbooks of the colonial period). The story of the raid has reverberated in Indian history, but largely during the (British) raj. It was first depicted as a trauma for the Hindu population not in India, but in the House of Commons. The triumphalist accounts of the event in Turko-Persian chronicles became the main source for most eighteenth-century historians. It suited everyone and helped the British to divide and rule a multi-millioned subcontinent.

In her new book, Romila Thapar, the doyenne of Indian historians, reconstructs what took place by studying other sources, including local Sanskrit inscriptions, biographies of kings and merchants of the period, court epics and popular narratives that have survived. The result is astounding and undermines the traditional version of what took place. These findings also contest the current Hindu religious nationalism that constantly utilises the conventional version of this history.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 30, 2023 at 5:20pm

-

If we were racist, why would we live with South Indians, black people around us: BJP’s Tarun Vijay

https://scroll.in/latest/833983/if-indians-were-racist-why-would-we...

He has apologised for the statement, which he made during an interview on Al Jazeera on the attacks on African nationals in Greater Noida.

Bharatiya Janata Party leader Tarun Vijay is facing criticism for responding to a question on the allegedly racist attacks on African nationals in Greater Noida by saying if India was, indeed, racist, we would not “live with” “black people around us”. “If we were racist, why would....all the entire South – you know, Kerala, Tamil, Andhra, Karnataka – why do we live with them?” He added, “We have blacks...black people around us.”

He made the statement during a discussion on TV channel Al Jazeera, while responding to another Indian panelist, Bengaluru-based photographer Mahesh Shantaram, who asked, “Why are people saying Indians are racist? Why are Indians saying Indians are racist? Why are people abroad and those who visit our beautiful nation feeling that Indians are racist?”

Vijay’s remarks triggered outrage soon after the interview was shared on social media. He took to Twitter to clarify his statement. “In many parts of the nation, we have different people, in colour and never, ever did we have any discrimination against them...My words, perhaps, were not enough to convey this,” he said, apologising to those who felt he spoke “differently from he meant”.

The BJP leader also said that Indians were the “first to oppose any racism and were, in fact, victims of the racist British”. Vijay explained that he had meant to convey how Indians did not face racism even though the country has “people with different colour and culture”. “I can die, but how can I ridicule my own culture, my own people and my own nation? Think before you misinterpret my badly-framed sentence,” he said, further claiming that he never called South Indians “black”.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 20, 2024 at 1:34pm

-

In India, one of the world’s most polyglot countries, the government wants more than a billion people to embrace Hindi. One scholar thinks that would be a loss.

By Samanth Subramanian

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/11/25/should-a-country-spea...

Since 2014, when the Bharatiya Janata Party (B.J.P.) came to power, it has made the future of Indian languages even more uncertain. In addition to its well-known Hindu fanaticism, the B.J.P. wishes to foist Hindi on the nation, a synthetic marriage that would clothe India in a monolingual monoculture. Across northern and central India, roughly three hundred million people speak, as their first language, the standardized Hindi that the B.J.P. holds dear—but, this being India, that leaves more than a billion who don’t. Even so, the government tried to make Hindi a mandatory language in schools until fierce opposition forced a rollback. The country’s Department of Official Language, which promotes the use of Hindi, has had its budget nearly tripled in the past decade, to about fifteen million dollars. A parliamentary committee recently urged that Hindi be a prerequisite for government employment, raising the possibility that such jobs might become the preserve of people from the B.J.P.’s Hindi-speaking heartland. Three years ago, India’s Home Minister called Hindi the “foundation of our cultural consciousness and national unity”—a message that he put out in a tweet written only in Hindi.

In India, where language scaffolds culture and identity, this pressure affects daily life. On social media, people routinely bristle at encountering Hindi in their non-Hindi-speaking states—on bank documents, income-tax forms, railway signboards, cooking-gas cylinders, or the milestones on national highways. Two years ago, a man set himself on fire in Tamil Nadu to protest the imposition of Hindi. In Karnataka, the state where he lives, Devy sees a simmering resentment of Hindi-speaking arrivals from the north.

The B.J.P. believes that India can cohere only if its identity is fashioned around a single language. For Devy, India’s identity is, in fact, its polyglot nature. In ancient and medieval sources, he finds earnest embraces of this abundance: the Mahabharata as a treasury of tales from many languages; the Buddhist king Ashoka’s edicts etched in stone across the land in four scripts; the lingua francas of the Deccan sultanates. The coexistence of languages, he thinks, has long allowed Indians to “accept many gods, many worlds”—an indispensable trait for a country so sprawling and kaleidoscopic. Preserving languages, protecting them from being bullied out of existence, is thus a matter of national importance, Devy said. He designed the P.L.S.I. to insure “that the languages that were off the record are now on the record.”

----------------

By the time (literary scholar Ganesh) Devy was born, Indian leaders had begun to regard language as an existential dilemma. This was a fresh, unstable country, already rent by strife between Hindus and Muslims; to mismanage the linguistic question would be to risk splintering India altogether. Mahatma Gandhi, fearing India wouldn’t hold without a national language, proposed that it be Hindustani, which encompasses both Hindi and the very similar Urdu of many Indian Muslims. (In the history of new nations, Gandhi’s concern is not an uncommon one.

---------

During his time in Vadodara, Devy had seen, up close, the rise of an ugly, intolerant Hindu fundamentalism. On the street one night, he encountered a Hindu mob hunting for Muslims to harm; he sent them in the wrong direction.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 22, 2024 at 8:40am

-

https://youtu.be/cbWI0YQOHvo?si=yS1_h_LU-Haxgy1F

"We've become a Muslim-hating country and face an existential crisis; I despair for my country, I don't see any ray of hope": Avay Shukla, one of India's most popular bloggers, to Karan Thapar for The Wire.

Comment

- ‹ Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- Next ›

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

US-India Ties: Does Trump Have a Grand Strategy?

Since the dawn of the 21st century, the US strategy has been to woo India and to build it up as a counterweight to rising China in the Indo-Pacific region. Most beltway analysts agree with this policy. However, the current Trump administration has taken significant actions, such as the imposition of 50% tariffs on India's exports to the US, that appear to defy this conventional wisdom widely shared in the West. Does President Trump have a grand strategy guiding these actions? George…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on August 31, 2025 at 6:30pm — 11 Comments

Humbled Modi Reaches Out to China After Trump Turns Hostile

Prime Minister Narendra Modi appears to be shedding his Hindutva arrogance. He is reaching out to China after President Donald Trump and several top US administration officials have openly and repeatedly targeted India for harsh criticism over the purchase of Russian oil. Top American officials have accused India, particularly the billionaire friends of Mr. Modi, of “profiteering” from the Russian…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on August 24, 2025 at 9:00am — 11 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network