PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

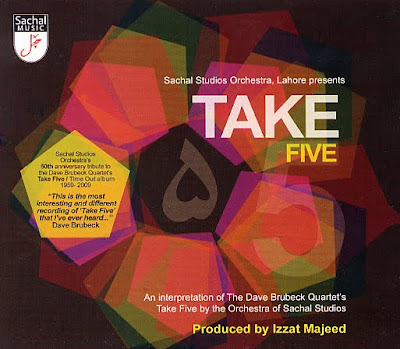

Pakistani Jazz Album Tops American and British Music Charts

It's the first time Jazz is being played in Pakistan in a big way since Jazz greats like Dave Brubeck, Duke Ellington and other jazz legends performed in the country in the 1950s. Brubeck, 90, told reporters that it is "the most interesting" version of Take Five he's ever heard.

Sachal Orchestra's first album, “Sachal Jazz,” with interpretations of tracks like “The Girl from Ipanema” and “Misty,” and of course “Take Five” is available on iTunes. It's been produced, financed and directed by a wealthy British Pakistani Jazz enthusiast Izzat Majeed.

Inspired by the Abbey Road Studios in London, Majeed and his partner Mushtaq Soofi have worked for the last six years with Christoph Bracher, a scion of a German musicians’ family, to design and set up Sachal Studios in Lahore where their albums have been recorded.

In addition to Sachal's jazz interpretation, there are now other signs of revival of uniquely Pakistani music. An example is Coke Studio. Sponsored by Coca Cola Pakistan, Coke Studio is a one-hour show that features musicians playing a distinct blend of fusion music that mixes traditional and modern styles. Helped by the media boom in Pakistan, the show has had dramatic success since it was launched three years ago. The popular show has crossed the border and inspired an Indian version this year.

Here's a brief video clip of Sachal orchestra performance:

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Pakistan's Other Story in 2010

Music Drives Coke Sales in Pakistan

History of Pakistani Music

Pakistan's Media Boom

Pakistan's Murree Brewery in KSE-100 Index

Health Risks in Developing Nations Rise With Globalization

Pakistan's Choice: Globalization Versus Talibanization

Life Goes On in Pakistan

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 20, 2011 at 9:16am

-

Here's a Dawn report on Ari Roland Jazz band performing "Dil Dil Pakistan" in Karachi:

KARACHI, Sept 16: An evening of jazz is what one usually gets to enjoy. A jazz morning is an unusual occurrence. But it happened on Friday when the Ari Roland Jazz Quartet from the US visited the National Academy of Performing Arts (Napa) to perform and conduct a brief workshop for the academy`s students. The morning turned out to be worth skipping one`s breakfast for.

The quarter comprises Ari Roland (double bass), Chris Byars (tenor saxophone), Zaid Nasser (alto saxophone) and Keith Balla (drums) and is in Pakistan for a five-day workshop. They kicked off their Napa visit with a number demonstrating the basics of the jazz genre. During the performance Keith Balla played on just one head of the drum because his drum set hadn`t arrived. It was a nice beginning to the (mini) gig as all the four musicians showed their skills during their solo acts in the composition.

Once the band was done with the song, Ari Roland explained how the quarter played jazz. He said while playing, the four musicians stuck to the same structure (chords etc) however, each one improvised a new melody. Replying to a question, Ari Roland said “if we don`t remember the melody, we can`t remember the harmony”. Since it was Zaid Nasser`s birthday, the quarter then presented the traditional happy birthday tune in jazz dedicating it to their saxophonist. They literally and figuratively jazzed up the number which was pleasing to the ear.

The band members told students and journalists that the last time they were in Pakistan they learned a word `jugulbandi`. According to them, the word is now commonly used in New York`s music circles.

Following up on the jugulbandi theme, the quarter played the famous Pakistani national song `Dil Dil Pakistan` (by Vital Signs) imparting it a completely jazzy feel. It was a unique experience listening to the song as Zaid Nasser and Chris Byars played the melody on their saxophones and Ari Roland created the correct rhythmic pattern on his double bass.

Then Ari Roland talked about the quartet`s drummer, Keith Balla, saying he was the youngest of the lot therefore had more energy. This was amply proved when the next song was performed. Keith Balla, who now had received his complete drum set, played with great vigour, control and passion earning a hearty applause from the audience.

Napa student Saima requested to play the guitar with the quarter, which the band gleefully accepted.

They played in B-flat key and despite the student`s nervy performance she was appreciated by her senior colleagues. This encouraged another Napa pupil, singer Nadir Abbas, to join the four American musicians for an improvisation of raag charukeshi.

Responding to one question about eminent Hollywood director and actor Woody Allen`s ability as a jazz player, Chris Byars said it was neither good nor bad. He also narrated a couple of amusing incidents related to Bill Clinton`s go at the genre.

http://www.dawn.com/2011/09/17/dil-dil-pakistan-jazz-style.html

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 10, 2012 at 5:51pm

-

Here's Indian writer Aakar Patel in FirstPost on Indian version of Coke Studio:

Why did Pakistan produce the lovely Coke Studio music series and not India? Why is Pakistan’s Coke Studio more popular with many Indians over the new Indian version? Is it because Pakistan’s musicians are better or more creative than India’s?

----------

One evening Ifti, who is sadly no longer with us, took me to the Waris Road residence of Masood Hasan, later to become a fellow columnist of mine at The News. We had a few glasses of the good stuff with some other guests, and then Hasan took us to a part of the property where his son Mekaal had built a studio and was playing with his band.This was when I first heard the music that is now so distinctively the sound of Coke Studio. I would define it as a folk song or raag-based melody, layered with western orchestration. This included a synthesizer wash, guitars, a drummer, a bass punctuating the chord changes, and backing vocals and harmony. Essentially it was traditional Hindustani music made palatable for ears accustomed to listening to more popular music.

Mekaal did this very well and his band’s first album, Sampooran, is as good as anything produced by Rohail Hyatt at Coke Studio later.

Indeed, many of the musicians Mekaal worked with, eventually ended up at Coke Studio. Gumby, the Karachi drummer on Coke Studio’s first four seasons, played on Sampooran. Zeb and Haniya, the stars of Coke Studio 2, were originally produced by Mekaal.

The first-rate Hindustani singer Javed Bashir who adds depth to the singers who are not classically trained, used to be lead singer with Mekaal’s band. The great Ghulam Ali was on a flight with me from Ahmedabad to Bombay once and I told him I was friends with Javed. “Mera hi bachcha hai,” he said with great pride.

Lahore’s Pappu, Pakistan’s best flutist, has played flute for Mekaal’s records.

Gumby and I went to a concert next to my house where guitarists Frank Gambale and Maurizio Colonna played. Gumby says Colonna’s playing brought tears to his eyes. Javed and I have drunk a few places dry, and been banned from one. Mekaal is of course a dear friend, as are Zeb and Haniya.

--------

Now to understand why India did not produce Coke Studio but Pakistan did. The reason is linked to what I said earlier – that Coke Studio is a popular interpretation of India’s traditional music.India’s talented musicians and producers have a commercial outlet:Bollywood. This is where money is made and this is where Pakistan’s singers who want commercial success must also come.

Their talent, however, is spent on making music that is purely popular, because that is what they are paid big money for. Indian musicians like Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy and Kailash Kher can make

Coke Studio’s sort of classical-popular mix of music easily if they set aside a couple of months for it. They choose not to however, because their working day is spent making music

that makes them rich (Kailash, whom I’ve known since before he sang for Bollywood, today charges Rs 20 lakh for a two hour concert).In Pakistan there is no commerce in music, and even the most talented musicians must do something other than sing or play to get by. Mekaal for instance, rents out his studio. The disadvantages of not having a commercial outlet for your talent are many. The only advantage of this is that musicians are free to make popular music that is still non-commercial.

Fortunately for all of us, whether Indian or Pakistani, Rohail Hyatt and his team have used this space to produce the music that we love so much. The reason why Coca Cola produces it is that the Pakistani public will not directly pay for it, unlike Indians and Bollywood.

It is cruel to say this, but it is true.

http://www.firstpost.com/living/why-pakistans-coke-studio-beats-ind...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 14, 2013 at 9:48pm

-

Here's an ET story on the use of music in cola wars in Pakistan:

Promoting a brand through sponsorship of music, it seems, has become an important marketing strategy for the world’s largest beverages manufacturers, at least in Pakistan. After phenomenal success of Coke Studio, a television music series sponsored by Coca-Cola Pakistan, the archrival PepsiCo has launched its own music show, Pepsi Smash.

The Pakistani subsidiary of the world’s largest beverages company successfully positioned itself as a higher-end aspirational brand through its sponsorship of Coke Studio, now five seasons old. Starting in 2008, the music series helped the company’s flagship soft drink gain a significant market share in Pakistan – the world’s sixth largest consumer market, dominated by market leader PepsiCo.

According to a Wall Street Journal report of July 2010, Pepsi has lost significant market share to Coca-Cola because of the latter’s sponsorship of Coke Studio. As of July 2010, Coke claimed 35% of all cola sales in Pakistan while Pepsi’s market share was 65%, down from a dominant 80% in the 1990s that it mainly gained by sponsoring cricket.Optimistic about future growth prospects, Coca-Cola announced this March that it would invest $379 million in three new bottling plants – one each in Karachi, Multan and Islamabad – that is in addition to another $172 million investment it announced in 2011.

The expansion plans come on the back of a strong growth in the company’s topline and volumes. Coca-Cola’s Pakistan arm earned over Rs50 billion in revenues for the financial year ending June 30, 2012, a 55% increase when compared with the previous year.

The improvement in distribution system and focus on consumer activation as well as promotion resulted in volume growth of 23% in the year 2012, according to Coca-Cola Içiçek, Turkey-based partner that has a 49% stake in Coca-Cola Beverages Pakistan – the Pakistani subsidiary of the US-based parent company that sells the product.

Coke Studio has helped the company dent Pepsi’s lead in cola wars, however, the latter still remains the largest player in what it sees as one of the top 10 non-US markets in the world.

“It is safe to say that PepsiCo is Pakistan’s most popular cola brand,” Pepsico spokesperson Mohammad Khosa said. The company has a lot of other exciting brands including Mountain Dew, 7Up, Mirinda, Slice, Sting and Aquafina that are doing wonderfully, he said.

Khosa refused to reveal the exact revenue or market share, but sources confirmed that revenues of PepsiCo Pakistan and its eight bottlers stood at a combined Rs82 billion for the financial year ending June 30, 2012, up 19% compared to the previous year.

Coca-Cola declined to comment on Pepsi Smash. Critics, however, see it as a sign of vulnerability of Pepsi’s lead. As opposed to the critics’ view that PepsiCo is copying its rival’s marketing strategy, Khosa said Pepsi Smash was launched to build on the brand’s longstanding association with music....

http://tribune.com.pk/story/552055/coke-and-pepsi-bank-on-showbiz-t...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 11, 2013 at 8:04pm

-

Here's a WSJ blog post on Izzat Majeed, a British-Pakistani music philanthropist:

The millionaire-investor-turned-philanthropist and music mogul will mark a milestone when his Sachal Studios Orchestra of Lahore releases its second jazz album later this year. The first, Sachal Jazz: Interpretations of Jazz Standards and Bossa Nova, went on sale in 2011. It shot to the top of iTunes rankings in both the U.S. and U.K. and drew comparisons to Ry Cooder’s Buena Vista Social Club album, done with Cuban’s biggest traditional musical legends, some of whom had been out of the limelight for decades.

The first Sachal album featured a version of “Take Five” that even Brubeck is said to have liked. Brubeck died late last year. The tribute to his quartet was played on both Western stringed instruments and traditional Eastern instruments, like the sitar, and was also done as a slickly cut, but somehow still-quaint music video.

The orchestra’s second album, Jazz and All That, has a decidedly different feel, Majeed said.

“For the second album, I’ve done two things. The entire structure of rhythm has changed. Also, I have brought in Western instruments that would create enthusiasm, rather than in the previous album, when the contribution of Western instruments was minimal,” he said. “That gels well with the sitar, the sarangi (a fiddle-like instrument)…It gives it a sound I really like.”

Sachal Studios, which also has produced several dozen albums from individual artists since opening, released a teaser video of the orchestra playing an East-West fusion version of R.E.M.’s “Everybody Hurts.”

Majeed, by the way, hesitates to call the sound of the orchestra he built “fusion,” though it blends elements and instruments of both.

“I shy away from Western or Eastern,” Majeed said. “I don’t understand ‘fusion.’ For example, I made two or three new tracks totally on our classical music, on the ragas. When you hear them, the raga is not disturbed at all…Whenever I make a composition and bring in an instrument from the West and our own instrument, ultimately, the impact, the sound that you hear, is your own music. It’s not fusion. It’s the world coming into musical harmony.”

Majeed, who is 63 and considers himself retired, splits time between London and Lahore, and does some of his album-tracking with musicians in Europe. He said he just likes the sound of the instruments coming together, and that part of his mission is to bring music back to Pakistan, even if it’s a different kind than what many of his countrymen expect.

“Everyone tells us, ‘you rock the boat all the time when you’re in Lahore, because I don’t know the music.’ We all just get together and say, ‘here is the sound. Do you like it?’ We bypass the classical structures,” he said.

Playing music that’s pleasant and interesting, as he discovered with the orchestra’s first album, attracts listeners from all over, like Japan and Brazil, as well as in Pakistan. Majeed said he started to compose the outlines of the second album as the first album began resonating with listeners around the world. It has come together at a comfortable pace and in a way where the whole orchestra is now onboard with the sound.

----

The new album features 13 tracks, including Henry Mancini’s “The PInk Panther,” “Eleanor Rigby,” “Morning has Broken” by Cat Stevens, “the Maquis Tepat,” and a jazz-based classical interpretation of a Monsoon raga.

Beyond the orchestra’s music, the tale of how and why Majeed built the studio and founded Sachal is worth telling for music aficionados.

After his initial exposure to U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s so-called “Jambassadors,” in 1958, Majeed, kept music close, despite a winding career.

http://blogs.wsj.com/speakeasy/2013/09/11/philanthropist-bringing-j...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 26, 2014 at 7:49am

-

Here's an excerpt of an NPR story on Sachal Jazz Orchestra in Lahore:

It recently released its second album, Jazz and All That. There's more Brubeck, among other Western classics by The Beatles, Jacques Brel, Antonio Carlos Jobim, R.E.M. — all with a South Asian flavor.

The weird thing is, Mushtaq Soofi says, while the old Lollywood session men are now winning plaudits abroad, no one back home knows or cares much about them.

"Music has to be recognized, and there is no patronage for music in Pakistan," Soofi says. "That is why people are upset, musicians are upset. If you sing, if you are a singer or a vocalist, you get kind of fame and name and money, but if you are a musician, a pure musician, people don't bother much about you."

The only people who do bother about you tend to be the religious extremists, like the Taliban.

"It is very difficult for musicians, because music is considered forbidden because it is un-Islamic," cellist Ghulam Abbas says. "Yet the same people think it is acceptable to kill people."

Be that as it may, Abbas says he isn't planning to hang up his cello again.

-----------

A few decades back, Lahore had a booming film industry. Inevitably, it was known as Lollywood."This was like a magic age that fell apart," says Aqeel Anwar, a violinist in his 70s. He used to play in Lollywood soundtracks. "It was such an excellent time. I never thought it would end."

For many years, South Asian movies kept Lahore's session musicians pretty busy. And the Lollywood musicians were a class apart.

"In Punjab here in Pakistan, music is usually practiced by traditional musicians' families," says Mushtaq Soofi, a music producer. "They inherit it, they learn it from their parents and then transmit to the next generation."

Things started to change in the late '70s. General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq seized power in a coup, ushering in a period of religious conservatism in Pakistan that lingers to this day.

Movie theaters began to shut down. Lollywood went into decline.

Ghulam Abbas played cello in the movies. When the work dried up, he packed away his instrument and broke with tradition by deciding not to teach his children how to play. He started up a garment stall, but struggled to get by.

"When I left this work, I was very sad," Abbas says. "I thought about how I'd worked hard and invested 25 to 30 years in my music."

Now, Abbas is sawing away at the cello again — though some of the music isn't exactly what he's used to.

http://www.npr.org/2014/04/26/306874889/a-millionaire-saves-the-sil...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 18, 2015 at 3:13pm

-

In 'Song Of #Lahore,' A Race To Revive Pakistani Classical Music. #Pakistan Documentary at #TribecaFilmFestival

The musicians are part of Sachal Studios Orchestra, a group of about 20 Lahore-based artists who fuse traditional Pakistani music with jazz. They work in a small rehearsal room in Sachal Studios, at the heart of the city. There, they create new songs and rehearse for concerts in effort to keep traditional music on the public's radar....Obaid-Chinoy's film follows the musicians on their quest.

The documentary premieres Saturday at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City......When they started in the early 2000s, the ensemble went largely unnoticed. Then in 2014, they performed in New York City with Wynton Marsalis and Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. This appearance earned them recognition in the global jazz scene. Since then, they've been performing around the globe and in Pakistan.

The documentary zooms into each musician's personal life before their success. For example, 39-year-old Nijat Ali is tasked to take over as conductor of the ensemble when his father dies. Saleem Khan, the violinist, struggles to pass on his skills to his grandson before it's too late. And 63-year-old guitarist Asad Ali tries to make ends meet by playing guitar in a local pop band.

The biggest challenge, Obaid-Chinoy says, was getting them to open up. "The musicians are very proud," she tells Goats and Soda. "When I first began filming them, they hid how tough life was for them, and it took me a long time to pry that open."

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 12, 2021 at 7:25am

-

‘There is no fear’: how a cold-war tour inspired Pakistan’s progressive jazz scene

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2021/jul/12/there-is-no-fear-how-...

One of the countries the US focused on was Pakistan, which had gained its independence from British colonial rule less than a decade earlier, in 1947: Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie and Dave Brubeck were among the performers at state-funded gigs during the 1950s and 60s. These concerts wove jazz into Pakistan’s musical fabric and through its traditional instruments, resulting in sounds that remain relatively unheralded yet are still flourishing today.

In attendance at Duke Ellington’s 1963 performance in Karachi was a teenager, Badal Roy. He had grown up in the city and was informally learning the tabla, a twinned set of drums. “At that time of my life I was mainly into Pakistani classical music and rock’n’roll – I loved Elvis Presley,” he tells me over the phone from his apartment in Wilmington, Delaware. “But that concert was my first introduction into jazz music. I had no idea what to expect and it was incredible.”

In attendance at Duke Ellington’s 1963 performance in Karachi was a teenager, Badal Roy. He had grown up in the city and was informally learning the tabla, a twinned set of drums. “At that time of my life I was mainly into Pakistani classical music and rock’n’roll – I loved Elvis Presley,” he tells me over the phone from his apartment in Wilmington, Delaware. “But that concert was my first introduction into jazz music. I had no idea what to expect and it was incredible.”

In 1968, he moved to New York in the hope of studying statistics at university. He struggled financially and worked as a busboy at A Taste of India, a restaurant in Greenwich Village, where he also began performing tabla each week.

Other musicians would sometimes come and jam. One guitarist, John McLaughlin, returned weekly, and asked Roy if he would join him on his album My Goal’s Beyond: Roy’s tabla became a key part of its sound. A few weeks later, McLaughlin returned to the restaurant and told Roy to pack up his tabla and come to the Village Gate club down the road as his friend wanted to hear him play. Upon arriving, Roy learned that this friend was Miles Davis, someone he knew nothing about. He was instructed to play. At the end of the 15-minute freestyle, Davis turned towards him and said: “You’re good.”

Advertisement

A couple of months after their encounter, Roy was asked to come into the studio and record, and found himself in a room with Davis, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Jack DeJohnette and more. Thankfully for his stress levels, he had very little knowledge of any of them. Davis told Roy: “You start.”

He began with the groove he played most often – TaKaNaTaKaNaTin – and shortly after, Herbie Hancock joined in, followed by the rest. The sessions ended up becoming Davis’s 1972 album On the Corner, and the simultaneous melody and rhythmic depth of Roy’s tabla helped to hold together its wild mix of funk and free jazz. “I was quite confused at first but when they started to play with me and we found the rhythm, I felt better,” Roy says. “I found it difficult to explain this instrument to them: how the tabla is tuned, how the language of the instrument is different, the rhythm pattern, everything. They are very clever, though, and they picked it up very quickly.”

hile Roy was busy working on pioneering albums such as Smith’s Astral Travelling and Sanders’ Wisdom Through Music, Pakistan was experiencing its own golden cultural age: its booming cinema industry was the fourth largest producer of feature films in the world during the early 70s. Almost every experimental, radical-sounding record that came out of mid-century Pakistan – many of them rooted in jazz – was from a film soundtrack. The elaborate acts of choreographed dancing and decadence expressed both organisation and chaos; sentiments that were reflected in the music, yielding a genre-shattering set of sounds.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 12, 2021 at 7:25am

-

‘There is no fear’: how a cold-war tour inspired Pakistan’s progressive jazz scene

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2021/jul/12/there-is-no-fear-how-...

A producer such as M Ashraf composed 2,800 film tracks in over 400 films across his 45-year career, aiding the careers of Pakistani singers such as Noor Jehan and Nahid Akhtar who would become some of the country’s most beloved singers. “An independent music space didn’t exist like it does now; radio was sticking to a more patriotic agenda and labels were limited in what they would champion,” explains musician and ethnomusicologist Natasha Noorani. “So, film is what you would rely on to see the deeper side of Pakistan’s culture. You could experiment with film, and that’s where the craziest records would come from” – ones where jazz clashed with pop, psychedelia and more.

The Lahore-based Tafo Brothers brought an entirely fresh dimension to Pakistan’s film music in the 70s, incorporating drum machines, analogue synths and fuzz pedals over the jazz infrastructure, allowing a more electronic, dancefloor-inclined energy to emerge. However, Pakistan’s cultural momentum stagnated in 1977 when military dictator Zia-ul-Haq seized power, and saw cinema, provoking different ideas and thoughts within the population, as a threat. Censorship laws curtailed creative independence. “If you study south Asian culture, the minute film is doing well, then your music industry is doing well too,” Noorani says. “By the late 70s, film began to be doing terribly and that was the moment the music industry collapsed.”

Session musicians and jazz players fell into unemployment and poverty, and gradually lost respect in a society where the creative arts were not a desirable field to work in. This had a damaging impact on the families who had preserved certain instruments for centuries, through a social system called gharānā. Suddenly, the attitudes towards some of the most historically respected figures in Pakistani society had completely shifted, and parents were contemplating whether or not to teach their children the instruments that had been the pillar of their family’s story.

Zohaib Hassan Khan is a member of one of Pakistan’s most esteemed sarangi-playing families from the Amritsar gharānā, which had been passing the instrument down each generation since the early 1700s. Khan is now continuing the tradition in the superb Pakistani jazz quartet Jaubi, part of a tiny yet imaginative new generation that also includes artists such as Red Blood Cat and VIP.

---------------

It was the same in 1956, when Dizzy Gillespie also appreciated the freedom within the rules. He spent afternoons between performances jamming with locals and street performers, trying to understand their musical approach, resulting in the track Rio Pakistan released the following year. It is arguably the first raga to be incorporated into American jazz, unfolding over 11 and a half minutes as Gillespie’s trumpet combines with the violin of Stuff Smith, combusting in a unique track that is noticeably limited in its melodic range.

The fearlessness of Khan, Baqar and Tenderlonious in working with their opposing approaches has resulted in similarly groundbreaking music: merging without ego or hierarchy, aided by the magic of improvisation, appreciating both rules and fluidity. It is the same approach that Gillespie took, and that Davis exemplified so boldly, incorporating Badal Roy’s tabla, an instrument known for its strictness, into an experimental free jazz album. Pakistan’s jazz players show that at a time when so many are conscious of what separates us, music can find a common ground in that very difference. As Roy puts it: “Our musical languages are different, but with patience, we learned to understand each other. That is when the real magic occurred.”

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 4, 2021 at 9:37pm

-

#Pakistani-#American singer Arooj Aftab inspired by Ghalib, Cohen and Rumi to create a unique fusion #music presentation: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/pakistani-musician-arooj-aftabs-n...

Arooj Aftab recently debuted work from her latest album at a concert at Brooklyn's Pioneer Works. Her compositions are personal, her performance intimate, but it was far from a solo effort.

----------------Audio engineering's loss was composing's gain. Where else would we get a song like "Last Night," with lyrics adapted from 13th century Sufi mystic and poet Rumi put to a beat like this one?

--------------------Her loss and her art converge in a composition called "Diya Haiti," its lyrics derived from a poem by the popular 19th century Indian poet Mirza Ghalib.

----------

Still, she had the self-assurance to take on a poet of more recent vintage, Leonard Cohen, and his celebrated composition "Hallelujah."

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 25, 2021 at 7:21am

-

5 Things to Know About 2022 Best New Artist Grammy Nominee Arooj Aftab

Check out five things you need to know about the best new artist nominee ahead of January's 64th annual Grammy Awards.

https://www.billboard.com/music/awards/arooj-aftab-grammy-nominatio...

When the 2022 Grammy nominations were announced Tuesday (Nov. 23), there was a name in this year’s pack of best new artist nominees that was likely unfamiliar to most American music fans: Arooj Aftab.

Tucked between the likes of Olivia Rodrigo, FINNEAS, The Kid LAROI and Jimmie Allen, the Pakistani multi-hyphenate is a Berklee College of Music-trained composer, producer and vocalist with three solo albums to her name and a fascinating life story to tell.

Ahead of the Jan. 31 ceremony, Billboard has rounded up five things you need to know about the best new artist contender. Check out all the nominees for the 64th annual Grammy Awards here, and learn about Aftab below.

1. She got her start as a pioneer of the Pakistani indie scene

In an April 2021 ArtForum profile, the Saudi Arabia-born artist revealed that she taught herself how to play guitar and learned to sing by listening to everyone from Billie Holiday and Mariah Carey to the late Indian singer Begum Akhtar. Once she started making her own music, Aftab became one of the first artists in Pakistan to promote herself using the Internet, with her covers of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” and Amir Zaki’s “Mera Pyar” going viral and helping establish the indie music scene in the country.

2. Her third album was released earlier this year

Aftab unveiled her latest studio effort, Vulture Prince, in May via New Amsterdam Records. The seven-track LP is rooted in a form of Arabic poetry known as the ghazal and contains acclaimed tracks such as “Mohabbat” and “Last Night,” as well as collaborations with multi-instrumentalist Darian Donovan Thomas (“Baghon Main”) and Brazilian singer Badi Assad (“Diya Hai”).

3. She went to Berklee College of Music

Now living in Brooklyn after moving to America in the mid-2000s to attend Berklee College of Music, Aftab originally grew up in Pakistan.

4. She has plenty of other nominations under her belt

While her Grammy nod is certainly a breakthrough moment, the Pakistani artist is no stranger to the awards circuit. Last year, Aftab picked up her first Latin Grammy in the best rap/hip-hop category for contributing to Residente’s “Antes Que El Mundo Se Acabe” as a backing vocalist. She also took home a Student Academy Award in 2020 for composing the music to Karishma Dev Dube’s short film Bittu, which also made the shortlist that year at the Oscars in the live action short film category.

5. She earned a shout-out from President Obama

Aftab’s music has earned her a pretty high-profile fan in former president Barack Obama. In July, the 44th president listed the artist’s song “Mohabbat” as one of his favorite tracks on his official summer 2021 playlist.

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Trump Administration Seeks Pakistan's Help For Promoting “Durable Peace Between Israel and Iran”

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio called Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif to discuss promoting “a durable peace between Israel and Iran,” the State Department said in a statement, according to Reuters. Both leaders "agreed to continue working together to strengthen Pakistan-US relations, particularly to increase trade", said a statement released by the Pakistan government.…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on June 27, 2025 at 8:30pm — 4 Comments

Clean Energy Revolution: Soaring Solar Energy Battery Storage in Pakistan

Pakistan imported an estimated 1.25 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of lithium-ion battery packs in 2024 and another 400 megawatt-hours (MWh) in the first two months of 2025, according to a research report by the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). The report projects these imports to reach 8.75 gigawatt-hours (GWh) by 2030. Using …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on June 14, 2025 at 10:30am — 3 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network