PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Pakistan Water Crisis: Facts and Myths

Pakistan is believed to be in the midst of a water crisis that is said to pose an existential threat to the country. These assertions raise a whole series of questions on the source of the crisis and possible solutions to deal with it. The New Water Policy adopted in April 2018 is a good start but it needs a lot more focus and continuing investments.

|

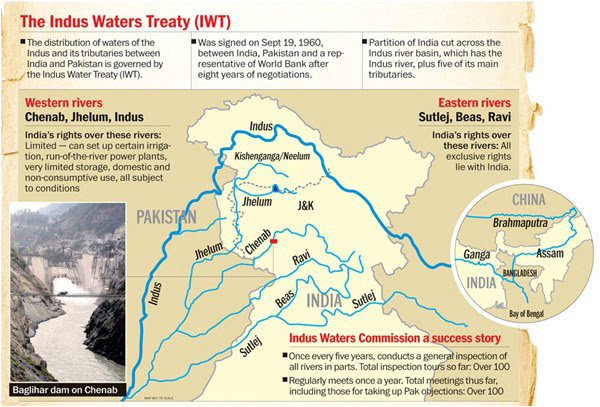

| Indus Water System. Courtesy: The Friday Times |

Questions on Water Crisis:

How severe is Pakistan's water crisis? Is India contributing to this crisis? How many million acre feet (MAF) of water flows in Pakistan? What are its sources? Glaciers? Rain? Groundwater? How much of it is stored in dams and other reservoirs? What is the trend of per capita water availability in Pakistan? What sectors are the biggest consumers of water in Pakistan? Why does agriculture consume over 95% of all available water? How can Pakistan produce "more crop per drop"? What are Pakistan's options in dealing with the water crisis? Build more dams? Recharge groundwater? Use improved irrigation techniques like sprinklers and drip irrigation? Would metering water at the consumers and charging based on actual use create incentives to be more efficient in water use?

Water Availability:

Pakistan receives an average of 145 million acre feet (MAF) of water a year, according to the Indus River System Authority (IRSA) report. Water availability at various canal headworks is about 95 million acre feet (MAF). About 50%-90% comes from the glacial melt while the rest comes from monsoon rains. Additional 50 MAF of groundwater is extracted annually via tube wells.

Pakistan Water Availability. Source: Water Conference Presentation |

The total per capita water availability is about 900 cubic meters per person, putting Pakistan in the water-stressed category.

India Factor:

What is the impact of India's actions on water flow in Pakistan? Under the Indus Basin Water Treaty, India has the exclusive use of the water from two eastern rivers: Ravi and Sutlej. Pakistan has the right to use all of the water from the three western rivers: Chenab, Jhelum and Indus. However, India can build run of the river hydroelectric power plants with minimal water storage to generate electricity.

Currently, India is not using all of the water from the two eastern rivers. About 4.6 million acre feet (MAF) of water flows into Pakistan via Ravi and Sutlej. Water flow in Pakistan will be reduced if India decides to divert more water from Ravi and Sutlej for its own use.

Secondly, India can store water needed for run-of-the-river hydroelectric plants on the western rivers. When new hydroelectric projects are built on these rivers in India, Pakistan suffers from reduced water flows during the periods when these reservoirs are filled by India. This happened when Baglihar dam was filled by India as reported by Harvard Professor John Briscoe who was assigned by the World Bank to work on IWT compliance by both India and Pakistan.

Pakistan is also likely to suffer when India ensures its hydroelectric reservoirs are filled in periods of low water flow in the three western rivers.

Water Storage Capacity:

Pakistan's water storage capacity in its various dams and lakes is about 15 million acre feet (MAF), about 10% of all water flow. It's just enough water to cover a little over a month of water needed. There are several new dams in the works which will double Pakistan's water storage capacity when completed in the future.

Since 1970s, the only significant expansion in water storage capacity occurred on former President Musharraf's watch when Mangla Dam was raised 30 feet to increase its capacity by nearly 3 million acre feet (MAF). Musharraf increased water projects budget to Rs. 70 billion which was reduced to Rs. 51 billion by PPP government and further decreased to Rs. 36 billion by PMLN government. It was only the very last PMLN budget passed by Shahid Khaqan Abbasi's outgoing government that increased water development allocation to Rs. 65 billion, a far cry from Rs. 70 billion during Musharraf years given the dramatic drop in the value of the Pakistani rupee.

Water Consumption:

Domestic, business and industrial consumers use about 5 million acre feet while the rest is consumed by the agriculture sector to grow food. Just 5% improvement in irrigation efficiency can save Pakistan about 7.5 million acre feet , the same as the current storage capacity of the country's largest Tarbela dam.

Given the vast amount of water used to grow crops, there is a significant opportunity to save water and increase yields by modernizing the farm sector.

National Water Policy:

Pakistan's Common Council of Interests (CCI) with the prime minister and the provincial chief ministers recently adopted a National Water Policy (NWP) in April 2018. It is designed to deal with “the looming shortage of water” which poses “a grave threat to (the country’s) food, energy and water security” and constitutes “an existential threat…”as well as “the commitment and intent” of the federal and provincial governments to make efforts “ to avert the water crisis”.

The NWP supports significant increases in the public sector investment for the water sector by the Federal Government from 3.7% of the development budget in 2017-18 to at least 10% in 2018-19 and 20% by 2030; the establishment of an apex body to approve legislation, policies and strategies for water resource development and management, supported by a multi- sectoral Steering Committee of officials at the working level; and the creation of a Groundwater Authority in Islamabad and provincial water authorities in each of the provinces.

More Crop Per Drop:

"More crop per drop" program will focus on improving water use efficiency by promoting drip and sprinkler irrigation in agriculture.

The Punjab government started this effort with the World Bank with $250 million investment. The World Bank is now providing additional $130 million financing for the Punjab Irrigated Agriculture Productivity Improvement Program Phase-I.

The project is the Punjab Government's initiative called High-Efficiency Irrigation Systems (HEIS) to more than doubles the efficiency of water use. Under the project, drip irrigation systems have been installed on about 26,000 acres, and 5,000 laser leveling units have been provided. The additional financing will ensure completion of 120,000 acres with ponds in saline areas and for rainwater harvesting, and filtration systems for drinking water where possible, according to the World Bank.

Groundwater Depletion:

Pakistan, India, and the United States are responsible for two-thirds of the groundwater use globally, according to a report by University College London researcher Carole Dalin. Nearly half of this groundwater is used to grow wheat and rice crops for domestic consumption and exports. This puts Pakistan among the world's largest exporters of its rapidly depleting groundwater.

Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources is working with United States' National Air and Space Administration (NASA) to monitor groundwater resources in the country.

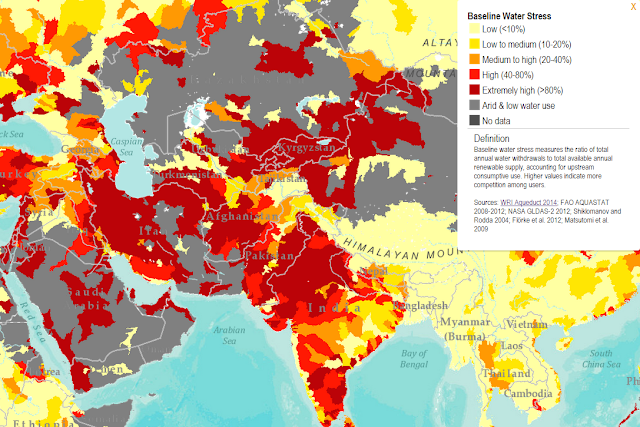

Water Stress Satellite Map Source: NASA |

NASA's water stress maps shows extreme water stress across most of Pakistan and northern, western and southern parts of India.

The US space agency uses Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) to measure earth's groundwater. GRACE’s pair of identical satellites, launched in 2002, map tiny variations in Earth's gravity. Since water has mass, it affects these measurements. Therefore, GRACE data can help scientists monitor where the water is and how it changes over time, according to NASA.

Aquifer Recharge:

Building large dams is only part of the solution to water stress in Pakistan. The other, more important part, is building structures to trap rain water for recharging aquifers across the country.

Typical Aquifer in Thar Desert |

Pakistan's highly water stressed Punjab province is beginning recognize the need for replacing groundwater. Punjab Government is currently in the process of planning a project to recharge aquifers for groundwater management in the Province by developing the economical and sustainable technology and to recharge aquifer naturally and artificially at the available site across the Punjab. It has allocated Rs. 582.249 million to execute this project over four years.

Summary:

Pakistan is in the midst of a severe water crisis that could pose an existential threat if nothing is done to deal with it. The total per capita water availability is about 900 cubic meters per person, putting the country in the water-stressed category. Agriculture sector uses about 95% of the available water. There are significant opportunities to achieve greater efficiency by using drop irrigation systems being introduced in Punjab. The New Water Policy is a good start but it requires continued attention with greater investments and focus to deal with all aspects of the crisis.

Here's a video discussion on the subject:

Related Links:

Groundwater Depletion in Pakistan

Cycles of Drought and Floods in Pakistan

Pakistan to Build Massive Dams

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 28, 2018 at 10:54am

-

Only big expansion in

#water storage occurred in#Musharraf years with Mangla Dam raised 30 ft to increase capacity by 3 million acre feet. Musharraf budgeted Rs. 70 billion for water,#PPP cut to Rs. 51 billion in 2013,#PMLN cut to Rs. 36 billion in 2017 https://www.southasiainvestor.com/2018/06/pakistan-water-crisis-facts-and-myths.html …

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 3, 2018 at 6:34pm

-

Every year since 2012, Bangalore has been hit by drought; last year Karnataka, of which Bangalore is the capital, received its lowest rainfall level in four decades. But the changing climate is not exclusively to blame for Bangalore’s water problems. The city’s growth, hustled along by its tech sector, made it ripe for crisis. Echoing urban patterns around the world, Bangalore’s population nearly doubled from 5.7 million in 2001 to 10.5 million today. By 2020 more than 2 million IT professionals are expected to live here.

https://www.wired.com/2017/05/why-bangalores-water-crisis-is-everyo...

Through the 2000s, Bangalore’s urban landscape expanded so quickly that the city had no time to extend its subcutaneous network of water pipes into the fastest-growing areas, like Whitefield. Layers of concrete and tarmac crept out across the city, stopping water from seeping into the ground. Bangalore, once famous for its hundreds of lakes, now has only 81. The rest have been filled and paved over. Of the 81 remaining, more than half are contaminated with sewage.

Not only has the municipal water system been slow to branch out, it also leaks like cheesecloth. In the established neighborhoods that enjoy the relative reliability of a municipal hookup, 44 percent of the city’s water supply either seeps out through aging pipes or gets siphoned away by thieves. Summers bring shortages, even for those served by the city’s plumbing. Everywhere, the steep ascent of demand has caused a run on groundwater. Well owners drill deeper and deeper, chasing the water table downward as they all keep draining it further. The groundwater level has sunk from a depth of 150 or 200 feet to 1,000 feet or more in many places.

The job of distributing water from an ever-shifting array of dying wells has been taken up, in large part, by informal armadas of private tanker trucks like the one Manjunath drives. There are between 1,000 and 3,000 of these trucks, according to varying estimates, hauling tens of millions of gallons per day through Bangalore. By many accounts, the tanker barons of Bangalore—the men who own and direct these trucks—now control the supply of water so thoroughly that they can form cartels, bend prices, and otherwise abuse their power. Public officials are fond of calling the tanker owners a “water mafia.”

That term, water mafia, conjures an image straight out of Mad Max—gangs of small-time Immortan Joes running squadrons of belching tankers, turning a city’s water on and off at will. When I first started to hear about Bangalore’s crisis, that lurid image was hard to square with the cosmopolitan city I knew from a lifetime of frequent visits. The prospect of Bangalore’s imminent collapse from dehydration, and its apparently anarchic response to the threat, seemed to offer a discomfiting preview of a more general urban future. As Earth warms, as cities swell, as resources become more scarce and vexing to distribute, the world’s urban centers will start to hit up against hard limits.

In the moment, though—well before the apocalypse—there was Manjunath. When his tanker had emptied itself, he chucked away his toothpick, climbed back into the cab, and set off once more for the bore well. Huawei’s reservoir would swallow many more loads before it was full.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 10, 2018 at 10:36pm

-

The Indus Inland Waterways System – the next big thing for Asia?

https://www.dawn.com/news/1241827

There are few river systems in the world as long and as reliable as the Indus. The river and its tributaries connect most major cities of Pakistan with each other and the Arabian Sea, but also Kabul in Afghanistan and the towns such as Gurdaspur and Ludhiana in India.

If a carefully engineered Indus Inland Waterways System (IIWS) is developed, connecting several cities in the three countries with the Arabian Sea, it could bring a huge economic boon in the entire region inhabited by 500 million people, including western China and Central Asia.

The economics and advantages of inland waterways are well documented, including in trade, commerce and engineering.

History of missed opportunities

Historically, this potential has existed since the times of British Raj. With the construction of Suez Canal in 1869, the British developed the port at Karachi and improved its transportation links with the interior through roads, railways and steamer services in the Indus.

Although proposals were put up for intercity linkage canals through the Indus, the British engineers saw more economic potential in building irrigation canals (a similar thing happened in the Ganges system).

While development of railways took care of inland transportation needs, the rivers were diverted into irrigation canals to transform the river basin into what is now known as the largest contiguous irrigation system of the world – IBIS (Indus Basin Irrigation System).

And it has sucked the rivers dry.

On the one hand, except for the monsoon months, the Indus delta receives very little to no flow going into the sea, and on the other, ever increasing irrigation demands are calling for damming or diverting even the leftover waters from the environmentally degraded rivers.

It seems almost impossible that the irrigation sector will let go its waters for maritime transportation.

The hope of agricultural efficiency

However, there is a ray of hope. The irrigation efficiency in IBIS is one of the lowest in the world. It is only half that of Imperial Valley in USA, and about two-third of its counterparts in Nile Valley and Indian Punjab.

Efficient irrigation can spare half the water being diverted from the rivers. This would only make economic sense if the water saved through efficiency can lead to more profit. IIWS provides that engine.

The International Monetary Fund's (IMF) 2015 World Economic Database reports that the agriculture sector’s total contribution to Pakistan’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is 23pc, or USD 60billion.

Irrigated agriculture provides approximately USD 45bn of this amount. In contrast, the Mississippi waterways serve approximately 200m people with an annual turnover of USD 70bn.

A fully developed IIWS would potentially serve more than 500m people in the region and could contribute to GDP far more than the current share of irrigated agriculture.

But IIWS will not replace agriculture, instead it will enhance agricultural productivity. Basin-scale investments in irrigation efficiency, therefore, make good economic sense.

Even with the current irrigation technologies being used efficiency can double, and with new emerging irrigation technologies we may be able to produce the same agricultural output with only a fifth of water.

A test run

The government of Punjab (GoP) has taken the initiative to test start a 200 kilometre commercial waterway in the Indus River between Attock and Daudkhel. Through a public private partnership, GoP has established the Inland Water Transport Development Company (IWTDC). The company’s mission is to ultimately connect Port Qasim with Nowshehra.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 5, 2018 at 4:22pm

-

ADB approves $100m loan to address Balochistan’s water shortage

A separate $2 million technical assistance from JFPR will help the provincial government improve its institutional capacity to address the risks and potential impact of climate change in the agriculture sector

https://en.dailypakistan.com.pk/pakistan/adb-approves-100m-loan-to-...

The Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) on Monday approved a $100 million loan to address chronic water shortages and increase earnings on farms in southwestern Pakistan province of Balochistan.

The Balochistan Water Resources Development Sector Project will focus on improving irrigation infrastructure and water resource management in the Zhob and Mula river basins, the ADB said in a statement.

“Agriculture is the backbone of Bolochistan’s economy,” said ADB Principal Water Resources Specialist Yaozhou Zhou. “This project will build irrigation channels and dams, and introduce efficient water usage systems and practices, to help farmers increase food production and make more money,” he added.

Among the infrastructure that will be upgraded or built for the project is a dam able to hold 36 million cubic meters of water, 276 kilometers of irrigation channels and drainage canals, and facilities that will make it easier for people, especially women, to access water for domestic use.

In total, about 16,592 hectares (ha) of land will be added or improved for irrigation.

The project will protect watersheds through extensive land and water conservation efforts, including planting trees and other measures on 4,145 ha of barren land to combat soil erosion.

Part of the project’s outputs are the pilot testing of technologies such as solar-powered drip irrigation systems on 130 ha of agricultural land, improving crop yields and water usage on 160 fruit and vegetable farms and demonstrating high-value agriculture development.

The project will also establish a water resources information system that will use high-level technology such as satellite and remote sensing to do river basin modelling and identify degraded land for rehabilitation.

ADB will also administer grants from the Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction (JFPR) and the High-Level Technology Fund (HLT Fund) worth $3 million and $2 million, respectively, for the project.

A separate $2 million technical assistance from JFPR will help Balochistan’s provincial government improve its institutional capacity to address the risks and potential impact of climate change in the agriculture sector, as well as build a climate-resilient and sustainable water resources management mechanism in the province.

JFPR, established in May 2000, provides grants for ADB projects supporting poverty reduction and social development efforts, while the HLT Fund, established in April 2017, earmarks grant financing to promote technology and innovative solutions in ADB projects.

ADB said it is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty.

Established in 1966, it is owned by 67 members of which 48 are from the region. In 2017, ADB operations totaled $32.2 billion, including $11.9 billion in co-financing.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 7, 2018 at 4:10pm

-

Here's what I found in World Bank sponsored research:

http://www.waterwatch.nl/fileadmin/bestanden/Project/Asia/0053_PK_2...

Crop yields show distinct North-South and East-West variations: wheat yields in the Indian Punjab average 29% higher than in the Pakistani Punjab to the west, and wheat yields in the Pakistani Punjab are 33% higher than in the Pakistani Sindh to the south. These spatial patterns of wheat yield are similar for 1984-85 and 2001- 02. Because crop evapotranspiration in the Pakistani Punjab and Indian Punjab are similar, the difference in crop yields between these two regions is also responsible for the difference in water productivity values. This important conclusion implies that increased water productivity can only be achieved by increased crop yields. Experiments of the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council across the country (n=41) have indicated that the overall yield of wheat can be increased by 54%, provided that inputs are optimal. Improved management of water quality (groundwater and canal water) and evacuation of drainage water are important components for improving agricultural production. Seed quality, fertilizers, and pesticide control should also be improved.

----------------

Water productivity values for wheat in 2001-02 (dry year) were higher due to increased solar radiation, which boosts crop growth when good quality groundwater is sufficiently available. During this 17-year period, yield increases were also due to improvements in farming practices and seed quality. In an average rainfall year, the water productivity for wheat in Pakistan (0.76 kg/m3) is 24% less than the global average (~1.0 kg/m3) and, therefore, can be classified as “moderately acceptable”. During the drought of 2001- 02, water productivities were at the same level as the global average. Hence, drought results in a more efficient utilization of water resources by wheat crops grown in the rabi (the dry winter season). Rice yield in the Punjab is on-average 24% higher than in the Sindh. The water productivity of rice (0.45 kg/m3) is 55% below the average value for rice in Asia (~1.0 kg.m3). Contrary to wheat, the water productivity of rice decreased during the 2001 drought, because rice is sensitive to water stress and to salinity that is intensified through increased tubewell withdrawals.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 20, 2018 at 7:03am

-

As to the water cutoff, it's just an empty threat by crazy Hindu Nationalists.

Can India really threaten Pakistan over water? TFT asked Jaweid Ishaque, an economist who has worked in agriculture and is editing a forthcoming monograph on water in Pakistan by Adnan Asdar Ali, a civil engineer with diverse experience in structural and forensic engineering, who has become an advocate for awareness on water in Pakistan.

TFT: Why have they left it like that?

JI: India has built a lot of dams—small dams. You need to undertand the geography to understand the politics. They will have to let the water through particularly from May to September which is peak monsoon flow season. It is all dhamki that they will stop our water.

Let’s assume India decides to store and build storage for 10MAF on the eastern rivers, which it could do. But the day India takes over 5% Pakistan can go to the IWC Tribunal or even the ICJ. Both these courses are open to us, without need for recourse to diplomatic spats or armed threats.

TFT: So India just sat there all these years?

JI: The IWT of 1960 has a clause that says that for 30 years, other than these approved projects, India and Pakistan can’t interfere in each other’s waters and cannot make any structures on rivers allocated to the other country. Even beyond the 30 years if India wishes to develop dams or barrages on the western rivers they will need to share the design so Pakistani experts can ensure that the parameters of minimum water storage are being complied with.

We are making them on the western rivers, but they are already approved. We did Mangla, then Tarbela and then we had approval for two or three more. We have exclusive use by the treaty. We can keep on making dams on these western rivers whether for hydel or storage.

India started planning in 1987 because the 30 years were to be over in 1990. They prepared for Wullar barrage in 1987 and for Baglihar around 1996-97. It was completed in 2011-12. Kishanganga started in 2007-2008 and is still being planned and it is a problem as it is on the Neelum. They state it is their river, which we dispute since it is a tributary of the Jhelum, meeting at Muzaffarabad and will directly impact the inflows into our river rights. These design features are still under adjudication by the Arbitrator under IWT provisions, which Pakistani experts are pursuing vigorously.

Whatever they did was after 1990. The clauses said you can do hydro, you can do run-of-the river and you can do storage, but not more than what the clauses specify, which is why we objected to the design of Baglihar and Wullar. In Wullar barrage our position was held up. In Baglihar our contention was modified. India had actually offered in 2008-09 that they were willing to modify the design just enough to to maintain what is called the mean dead level.

You are allowed to keep a mean dead level of water otherwise the damn starts to silt up. But the PPP government at the time insisted on going to the international court. At the end of the day, even if there is a difference of say 1MAF, is it worth bad relations?

https://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/can-india-really-threaten-pakist...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 28, 2018 at 4:36pm

-

#Pakistan Faces A Water #War With #India On The Horizon. Glaciers feeding Indus originate in India, which has implemented large-scale diversions of freshwater. India has even bigger plans for diversions. #IWT #Indus #Dams #DamsForPakistan #ClimateChange https://www.sciencefriday.com/articles/pakistan-faces-a-water-war-o...

Pakistan is one of the fastest-growing nations in the world. It had a population of 170 million in 2011. Five years later, that population crossed the 200 million mark. The country is grappling with the same sorts of growing pains that its neighbor, India, is experiencing.

But Pakistan has an extraordinary problem looming on the horizon: water scarcity, which has devastated other countries in the sub-tropics in the past decade, is now quite real. And a solution to the crisis is not entirely within the country’s control.

But here’s where it gets especially treacherous for Pakistan. Compounding the over-use and changes inflicted on the arid region from the Earth’s climate system, actions by India to cut off some of the flow of water feeding the Indus has created the potential for serious conflict between the two nations.

The glaciers that feed the Indus originate in India, which has implemented large-scale diversions of the freshwater as it cascades down from those glaciers. India has even bigger plans for diversions. This, not surprisingly, has created considerable tension with Pakistan.

“One of the potentially catastrophic consequences of the region’s fragile water balance is the effect on political tensions,” National Geographic reported.

“In India, competition for water has a history of provoking conflict between communities. In Pakistan, water shortages have triggered food and energy crises that ignited riots and protests in some cities. Most troubling, Islamabad’s diversions of water to upstream communities with ties to the government are inflaming sectarian loyalties and stoking unrest in the lower downstream region of Sindh.

“But the issue also threatens the fragile peace that holds between the nations of India and Pakistan, two nuclear-armed rivals. Water has long been seen as a core strategic interest in the dispute over the Kashmir region, home to the Indus’ headwaters,” it wrote. “Dwindling river flows will be harder to share as the populations in both countries grow and the per-capita water supply plummets.”

A bit of context is necessary here to understand how severe a problem this is right now for Pakistan—and how it can become catastrophic in the near future.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—a definitive report on the causes and impacts of climate change globally compiled by thousands of scientists every four years—has signaled for nearly a decade now that dry regions of the world in the sub-tropics will continue to see less and less rainfall. Some of this is already occurring. The Horn of Africa (which includes Somalia, Yemen, and Kenya) falls squarely in the sub-tropics where decreased rainfall has a severe impact on already dry regions. India and Pakistan do as well. The overall effect of climate change is an intensification of the water cycle that causes more extreme floods and droughts globally. The sub-tropical regions of the world are ground zero for these impacts.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 28, 2019 at 9:51pm

-

Glacier Watch: Indus Basin

BACKGROUNDERS - May 21, 2019

By Geopolitical Monitor

https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/glacier-watch-indus-basin/

The Indus Basin covers an area of around 1.1 million square kilometers, starting in the Hindu Kush, Karakorum, and Himalaya mountains before draining into the Arabian Sea in a vast 600,000-hectare delta. Upstream portions incorporate parts of China, Afghanistan, and India, while most of the downstream area falls within Pakistan. The system feeds the 3,000 km-long Indus River, which is the 8th longest in the world.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the Indus Basin system to the 237 million people who live within it. The basin’s waters are essential for drinking, food security, and the health of local, fishing-based economies in Pakistan. Fish production (which is 63% marine and 37% inland) accounts for one of Pakistan’s top-10 exports. The health of these communities is an important and oft-unquantifiable consideration; their economic collapse generally leads to rapid urbanization, sectarian conflict, and popular upheaval against the state authorities.

Aquaculture is one economic standout, as the industry is one of the fastest growing in the world and it already contributes 1% of Pakistan’s GDP. Yet the industry is already in trouble: it’s growing at just 1.5% per year, far behind the rate in neighbors like India and Bangladesh, and some are even predicting the collapse of aquaculture in Pakistan within 20 years. At fault is years of unregulated overfishing, along with dam-building and climate change which are destroying species diversity. The problem is especially pronounced in the 600,000 hectares of mangrove forests in the Indus Delta. The unique mangrove ecosystem is ideal for shrimp farming, one of the most value-added fields of aquaculture. But the mangrove forests have been dying out as the Indus’ flow weakens; it’s estimated that some 86% of mangrove cover has been lost between 1966 and 2003 – and it’s likely that the trend has progressed since then.

Reduced flow along the Indus has allowed saltwater to slowly creep upstream, rendering previously arable land unusable and forcing locals to uproot and move in search of greener pastures. There’s some 33 million hectares of cultivated cropland within the basin, served by an irrigation system of 40,000 miles of canals and 90,000 watercourses, all drawing water from the Indus along with other rivers like the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, and Sutlej.

Agriculture is a major part of Pakistan’s economy: some 24 million people are engaged in cultivation – or 40% of the economically active population – and the sector accounted for 22% of Pakistan’s GDP in 2009. Agricultural products are also lucrative export goods for Pakistan – a country that is currently grappling with a severe balance of payments crisis. Food exports account for around 13% of Pakistan’s total exports, and are a rare case of year-on-year growth. Rice is of particular importance, representing 60% of Pakistan’s food exports. It is one of the main crops that’s cultivated in the Indus Basin, which, along with wheat and cotton, represent 77% of the total irrigated area. It is also an extremely water-hungry crop, making it reliant on heavy water extraction.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 1, 2019 at 9:57am

-

A farmer in Punjab is rejuvenating sand dunes though drip irrigation

Zofeen T. Ebrahim Updated June 01, 2019

https://www.dawn.com/news/1485906

For as long as Hasan Abdullah can remember the 50-acre sandy dune on his 400-acre farmland in Sadiqabad, Pakistan’s Punjab province, was an irritant – nothing grew on it.

His farmland lies beside the vast Cholistan desert in a canal irrigated area east of the Indus River in Rahim Yar Khan district. Abdullah inherited it in 2005, when his father passed away. Until then he had been working in information technology.

In 2015, after much research, Abdullah took a “calculated risk” of cultivating the “barren” dune using the drip irrigation system. The government’s announcement of a 60% subsidy on drip irrigation was “a big incentive,” he said. Agriculture, through wasteful flood irrigation, accounts for over 80% water usage in a country facing severe water shortages.

Today, Abdullah’s dune is a sight to behold: fruit orchards have flourished in the sand. He admitted that without drip irrigation the “dune would never have produced anything.

Water mixed with fertiliser is carried out through pipes with heads known as drippers, explained Abdullah, which release a certain amount of water per minute directly to the roots of each plant across the orchard.

And because watering is precise, there is no evaporation, no run off, and no wastage.

---

The power of the drip

Using drip irrigation, farmers can save up to 95% of water and reduce fertiliser use, compared to surface irrigation, according to Malik Mohammad Akram, director general of the On Farm Water Management (OFWM) wing in the Punjab government’s agriculture department. In flood irrigation – the traditional method of agriculture in the region – a farmer uses 412,000 litres per acre, while using drip irrigation the same land can be irrigated with just 232,000 litres of water, he explained.

The water on Abdullah’s dune is pumped from a canal – which is part of the Indus Basin irrigation system – into a reservoir built on the land. “Being at the tail end [of the canal system], we needed to be assured the availability of water at all times and thus we had to construct a reservoir,” said Abdullah. For years now, farmers at the head of the canals have been “stealing” water causing much misery for farmers downstream.

Costly savings

But drip irrigation is expensive. Out of Abdullah’s 40 acres of orchards on drip irrigation, 30 acres are on sand dunes and ten acres are on land adjacent to the dune, locally known as “tibba” – a small sand dune surrounded by agricultural land. On the 30 acre-dune patch, Abdullah grows oranges on 18, feutral (another variety of orange) on another six acres, lemons on five acres and on one acre he has experimented with growing olives, which bore fruit this year.

In took three years of “micromanaging the orchards” before the orange and olive trees began fruiting last year. “We hope to break even this year and next year we should be in profit,” he said. It will take another four years to recoup all his investment, he calculated.

Abdullah was the first farmer to experiment with this new approach. Among many challenges that came his way was to get his farmhands to understand the new way of watering.

Akram has had a similar experience, “It is difficult for a traditional farmer to come to terms with it. Unless he sees the soaked soil with his eyes, he cannot believe the plant has been well watered.”

---

---

“Ours is the only farm in Pakistan that has set up a drip irrigation system over such a huge tract – and in the desert too,” said Asif Riaz Taj, who manages Infiniti Agro and Livestock Farm. Now in their fourth year, the orchards have started fruiting over 70 acres. But it will not be before its sixth year, Taj said, that they will “break even”. The drip irrigation and solar plant was installed at a cost of PKR 25 million (USD 174,000), and the monthly running cost of this farm is almost PKR 4 million (USD 28,000).

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 1, 2019 at 10:14am

-

#Pakistani #Punjab government giving 60% subsidy to promote #drip #irrigation in #farming for conserving #water and getting higher crop yield. Also helps save fertilizer, time, labor. #Agriculture #Pakistan https://fp.brecorder.com/2019/06/20190601483027/

The Punjab government is providing 60 percent subsidy to the growers on promotion of latest irrigation techniques including drip irrigation in the province with an aim of conserving water and getting more yield. Director General Agriculture (Water Management) Malik Muhammad Akram said that latest irrigation techniques ensure availability of water and fertilizer in time to the plants and it also ensure uniform supply of these two major ingredients to all the plants in a field. It helps attaining more per acre yield with minimum agricultural inputs, he added.

He said that it also help saving fertilizer, time, labour and water by fifty per cent while a lot of water go waste in the traditional watering techniques. He said in this system water goes to plants' roots in shape of drops. This system is also very successful on uneven land or land in Potohar or desert areas. He said there is a need to attract farmers to drip irrigation system as it would help mitigate the negative impact of water shortage or impacts of climate change thus leading the country to self-reliance in food.

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Pakistani Prosthetics Startup Aiding Gaza's Child Amputees

While the Israeli weapons supplied by the "civilized" West are destroying the lives and limbs of thousands of Gaza's innocent children, a Pakistani startup is trying to provide them with free custom-made prostheses, according to media reports. The Karachi-based startup Bioniks was founded in 2016 and has sold prosthetics that use AI and 3D scanning for custom designs. …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on July 8, 2025 at 9:30pm

Indian Military Begins to Accept Its Losses in "Operation Sindoor" Against Pakistan

The Indian military leadership is finally beginning to slowly accept its losses in its unprovoked attack on Pakistan that it called "Operation Sindoor". It began with the May 31 Bloomberg interview of the Indian Chief of Defense Staff General Anil Chauhan in Singapore where he admitted losing Indian fighter aircraft to Pakistan in an aerial battle on May 7, 2025. General Chauhan further revealed that the Indian Air Force was grounded for two days after this loss. …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on July 5, 2025 at 10:30am — 6 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network