PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Pakistan's Total Education Spending Surpasses its Defense Budget

Pakistan's public spending on education has more than doubled since 2010 to reach $8.6 billion a year in 2017, rivaling defense spending of $8.7 billion. Private spending on education by parents is even higher than the public spending with the total adding up to nearly 6% of GDP. Pakistan has 1.7 million teachers, nearly three times the number of soldiers currently serving in the country's armed forces. Unfortunately, the education outcomes do not yet reflect the big increases in spending. Why is it? Let's examine this in some detail.

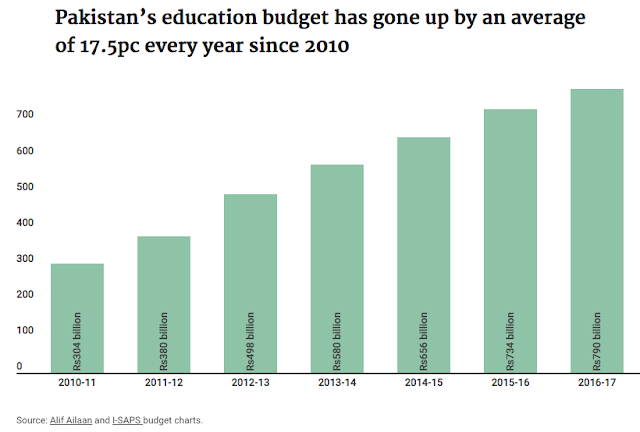

Pakistan Education Budget:

The total money budgeted for education by the governments at the federal and provincial levels has increased from Rs. 304 billion in 2010-11 to Rs. 790 billion in 2016-17, representing an average of 17.5% increase per year since 2010.

|

| Source: Dawn Newspaper |

Private Education Spending in Pakistan:

2012 Data from UNESCO and the World Bank shows that the private spending on education is about twice as much as the monies budgeted by federal and provincial governments in Pakistan.

Private/Public Spending on Education in Selected Countries. Source:... |

Education Outcomes:

UNESCO and World Bank data from 2013 shows that only 52% of Pakistani kids and 48% of Indian kids reached expected standard of reading after 4 years of school, according to the Economist Magazine. It also shows that 46% of Pakistani children dropped out of school before completing 4 years of education.

Reading Performance in Selected Countries. Source: Economist |

Education and Literacy Rates:

Pakistan's net primary enrollment rose from 42% in 2001-2002 to 57% in 2008-9 during Musharraf years. It has been essentially flat at 57% since 2009 under PPP and PML(N) governments.

Similarly, the literacy rate for Pakistan 10 years or older rose from 45% in 2001-2002 to 56% in 2007-2008 during Musharraf years. It has increased just 4% to 60% since 2009-2010 under PPP and PML(N) governments.

Pakistan's Human Development:

Human development index reports on Pakistan released by UNDP confirm the ESP 2015 human development trends.Pakistan’s HDI value for 2013 is 0.537— which is in the low human development category—positioning the country at 146 out of 187 countries and territories. Between 1980 and 2013, Pakistan’s HDI value increased from 0.356 to 0.537, an increase of 50.7 percent or an average annual increase of about 1.25.

Pakistan HDI Components Trend 1980-2013 Source: Human Development R... |

Overall, Pakistan's human development score rose by 18.9% during Musharraf years and increased just 3.4% under elected leadership since 2008. The news on the human development front got even worse in the last three years, with HDI growth slowing down as low as 0.59% — a paltry average annual increase of under 0.20 per cent.

Going further back to the decade of 1990s when the civilian leadership of the country alternated between PML (N) and PPP, the increase in Pakistan's HDI was 9.3% from 1990 to 2000, less than half of the HDI gain of 18.9% on Musharraf's watch from 2000 to 2007.

Bogus Teachers in Sindh:

In 2014, Sindh's provincial education minister Nisar Ahmed Khuhro said that "a large number of fake appointments were made in the education department during the previous tenure of the PPP government" when the ministry was headed by Khuhru's predecessor PPP's Peer Mazhar ul Haq. Khuhro was quoted by Dawn newspaper as saying that "a large number of bogus appointments of teaching and non-teaching staff had been made beyond the sanctioned strength" and without completing legal formalities as laid down in the recruitment rules by former directors of school education Karachi in connivance with district officers during 2012–13.

Ghost Schools in Balochistan:

In 2016, Balochistan province's education minister Abdur Rahim Ziaratwal was quoted by Express Tribune newspaper as telling his provincial legislature that “about 900 ghost schools have been detected with 300,000 fake registrations of students, and out of 60,000, 15,000 teachers’ records are unknown.”

Absentee Teachers in Punjab:

A 2013 study conducted in public schools in Bhawalnagar district of Punjab found that 27.5% of the teachers are absent from classrooms from 1 to 5 days a month while 3.75% are absent more than 10 days a month. The absentee rate in the district's private schools was significantly lower. Another study by an NGO Alif Ailan conducted in Gujaranwala and Narowal reported that "teacher absenteeism has been one of the key impediments to an effective and working education apparatus."

Political Patronage:

Pakistani civilian rule has been characterized by a system of political patronage that doles out money and jobs to political party supporters at the expense of the rest of the population. Public sector jobs, including those in education and health care sectors, are part of this patronage system that was described by Pakistani economist Dr. Mahbub ul Haq, the man credited with the development of United Nation's Human Development Index (HDI) as follows:

"...every time a new political government comes in they have to distribute huge amounts of state money and jobs as rewards to politicians who have supported them, and short term populist measures to try to convince the people that their election promises meant something, which leaves nothing for long-term development. As far as development is concerned, our system has all the worst features of oligarchy and democracy put together."

Summary:

Education spending in Pakistan has increased at an annual average rate of 17.5% since 2010. It has more than doubled since 2010 to reach $8.6 billion a year in 2017, rivaling defense spending of $8.7 billion. Private spending by parents is even higher than the public spending with the total adding up to nearly 6% of GDP. Pakistan has 1.7 million teachers, nearly three times the number of soldiers currently serving in the country's armed forces. However, the school enrollment and literacy rates have remained flat and the human development indices are stuck in neutral. This is in sharp contrast to the significant improvements in outcomes from increased education spending seen during Musharraf years in 2001-2008. An examination of the causes shows that the corrupt system of political patronage tops the list. This system jeopardizes the future of the country by producing ghost teacher, ghost schools and absentee staff to siphon off the money allocated for children's education. Pakistani leaders need to reflect on this fact and try and protect education from the corrosive system of political patronage networks.

Related Links:

History of Literacy in Pakistan

Reading and Math Performance in Pakistan vs India

Myths and Facts on Out-of-School Children

Who's Better For Pakistan's Human Development? Musharraf or Politic...

Corrosive Effects of Pakistan's System of Political Patronage

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 6, 2023 at 5:17pm

-

https://www.educationnext.org/no-school-stands-alone-how-market-dyn...

Jishnu Das

The high concentration of private and public schools in Punjab Province has transformed education markets there. Figure 1 shows a village in the LEAPS sample. It took me (and two young children) 15 minutes to traverse the village, yet it has five private and two public schools. Data gathered by the LEAPS team show that in 2003, the average fee for private schools in rural Punjab was equivalent to about $1.50 a month, or less than the price of a cup of tea every day. The number of schools in the village portrayed here is typical of the sample—in fact, the average LEAPS village in 2003 had 678 households and 8.2 schools, of which 3 were private.

The proliferation of private schools in Punjab has enabled such considerable school choice that, once we account for urban areas, some 90 percent of children in the province now live in neighborhoods and villages like the one illustrated in Figure 1. Such “schooling markets” are not just a Pakistani or South Asian phenomenon. Schooling environments in Latin America and parts of Sub-Saharan Africa also offer extensive variety for local families.

One question widely examined by education researchers is whether children in private schools learn more than those in public schools. Is there a private-school “premium” that can be measured in terms of test results or other metrics? One impediment to answering that question is that children enrolled in private schools are not randomly drawn from the local population, and researchers often cannot convincingly correct for this selection problem. In my view, though, a larger obstacle is that the concept of an “average” private-school premium is elusive when families can choose from multiple public and private schools and the quality of schools differs vastly within both sectors. Comparing a high-performing public school to a low-performing private school will yield a very different result than comparing a high-performing private school to a low-performing public school.

The LEAPS research team looked at this question in a study published in 2023. We defined school value-added as the gain in test scores in Urdu, math, and English that a randomly selected child would experience when enrolled in a specific school. The team found that the value-added variation among schools was so large that, compounded over the primary school years, the average difference between the best- and the worst-performing school in the same village was comparable to the difference in test scores between low- and high-income countries.

Figure 2 shows what this variation implies for estimates of private-school effectiveness. Each vertical line in the figure represents one of the 112 LEAPS villages. Schools in each village are arranged on the line according to their school value-added, with public schools indicated by red triangles and private schools by black dots. The red band tracks the average quality of public schools in the villages, from weakest to strongest, and the gray band shows the average quality of private schools in the villages. The private schools are, on average, more successful in raising test scores than their public-sector counterparts. As is clear, however, every village has private and public schools of varying quality, and the measure of any “private-school premium” depends entirely on which specific schools are being compared. In fact, the study shows that the causal impact of private schooling on annual test scores can range from –0.08 to +0.39 standard deviations. The low end of this range represents the average loss across all villages when children move from the best-performing public school to the worst-performing private school in the same village. The upper end represents the average gain across all villages when children move from the worst-performing public school to the best-performing private school, again within the same village.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 6, 2023 at 5:18pm

-

https://www.educationnext.org/no-school-stands-alone-how-market-dyn...

Jishnu Das

Parents’ Choices

The relevant question, then, is not whether private schools are more effective. The questions are: How well are parents equipped to discern quality in a school—public or private—and choose the best one for their children? And can policy decisions affect these choices?

As to the first question, the team found that parents choosing private schools appear to recognize and reward high quality. Consequently, in the LEAPS villages, private schools with higher value-added are able to charge higher fees and see their market share increase over time. In contrast, parents choosing public schools either have a harder time gauging the school’s value-added or are less quality-sensitive in their choices. This is particularly concerning in the case of students enrolled in very poorly performing public schools where after five years of schooling they may not be able to read simple words or add two single-digit numbers.

Given that parents who opt for public schools appear to be less sensitive to quality, one reform instrument often supported by policymakers is the school voucher, whereby public money follows the child to the family’s school of choice. The idea is that making private schools “free” for families will allow children to leave poorly performing public schools in favor of higher-quality private schools. This strategy assumes that parents, when choosing among schools, place significant weight on the cost of the school, manifest in its fees. What’s more, one may reasonably expect that such “fee sensitivity” will be higher in low-income countries and among low-income families. Yet a 2022 analysis of the LEAPS villages showed that a 10 percent decline in private-school fees increased private-school enrollment by 2.7 percent for girls and 1 percent for boys. From these data we estimated that even a subsidy that made private schools totally free would decrease public-school enrollment by only 12.7 and 5.3 percentage points for girls and boys, respectively. This implies that most of the subsidy, rather than going to children who are leaving public schools, would be captured by children who would have enrolled in private schools even without the tuition aid. Further, most of the children induced to change schools under the policy may come from high- rather than low-performing public schools, limiting any test-score gains one might expect.

One alternative to trying to move children out of poorly performing public schools is to focus on improving those schools. A LEAPS experiment that my co-authors and I published in 2023 evaluated a program that allocated grants to public schools in villages randomly chosen from the LEAPS sample. We found that, four years after the program started, test scores were 0.2 standard deviations higher in public schools in villages that received funds than in public schools in villages that did not. In addition, we observed an “education multiplier” effect: test scores were also 0.2 standard deviations higher in private schools located in grant-receiving villages. This effect echoes an economic phenomenon that often occurs in industry—that is, when low-quality firms improve, higher-quality firms tend to increase their quality even further to protect their market share. In the LEAPS villages, the private schools that improved were those that faced greater competition, either by being physically closer to a public school or by being located in a village where public schools were of relatively high quality at the start of the program. The same was true of private schools in villages where the grants to the public schools were larger.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 6, 2023 at 5:19pm

-

https://www.educationnext.org/no-school-stands-alone-how-market-dyn...

Jishnu Das

The education multiplier effect increases the cost-effectiveness of the grant program by 85 percent, putting it among the top ranks of education interventions in low-income countries that have been subject to formal evaluation. But beyond that, accounting for private-school responses also changed the optimal targeting of the policy. For instance, our analysis shows that if policymakers consider test-score increases in public schools only, a policy that divides resources equally across villages also maximizes test-score gains; there is apparently no trade-off between equity and effectiveness. Once private-school responses are considered, however, equal division of resources exacerbates existing inequalities in learning among villages. This implies that a government that values equity should distribute more resources to villages with poorly performing public schools.

Implications for Policymaking

With 90 percent of Pakistani children living in neighborhoods with multiple public and private schools, the days when government could formulate policies that affected only public schools are long gone. The same is true of many other low-income countries where parents also have significant school choice, ranging from Chile to India. Every policy will have an impact on both public and private schools, even if a policy only targets public schools. Policymakers can choose to ignore these additional effects, but to do so is to miscalculate the policy’s full impact. Our studies are still too premature to help factor parental and private-school responses into the design of policy. A key insight from the LEAPS research is that there is significant variation among schools in terms of performance and among parents in terms of their preferences for quality. A policy to improve public schools can lead to an education multiplier effect in one context but cause private schools to exit in another. A broad understanding of the dynamics of education markets, such as parents placing a very heavy weight on physical distance to school in their choices, can shed some light on this variation. Yet the data requirements to make detailed predictions about how policies will play out in specific settings may be too onerous, at least for now.

How then to proceed? Three broad principles are emerging from the LEAPS project.

First, there is little evidence that parents choosing to send their children to private schools in low-income countries are being fooled or hoodwinked into receiving a substandard education. On the contrary, the parents choosing private schools seem to be more informed and better able to reward school quality. The bigger problem is the substantial population of children enrolled in very low-performing public schools, even when there are better public schools nearby. Unfortunately, policies that seek to move children from public to private schools by means of vouchers may end up spending a lot of money on children who were already going to private schools. What’s more, the test-score gains from such policies may be limited if most of the children who do switch from a public to a private school come from higher-performing public schools. Indeed, a 2022 study by Mauricio Romero and Abhijeet Singh showed that both of these dynamics play out in India’s Right to Education Act, which established one of the world’s largest voucher schemes. Subsidizing private schools in a way that consistently improves test scores by moving children out of low-performing public schools remains an elusive goal.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 6, 2023 at 5:19pm

-

https://www.educationnext.org/no-school-stands-alone-how-market-dyn...

Jishnu Das

If we cannot move children out of low-performing public schools, the alternative is to improve those schools. The second principle, then, is that governments should maintain a focus on improving the quality of public schools. Results of the first generation of efforts to do so in low-income countries were mixed at best, but studies of newer reform efforts that emphasize improved pedagogy, incentives, teacher recruitment and training, and school grants are all showing positive results. A 2021 study by Alex Eble and colleagues, for instance, showed dramatic improvements in test scores in The Gambia with an intervention that used a variety of strategies: hiring teachers on temporary contracts, making changes in pedagogy, monitoring teachers, and giving them regular feedback. Again, the benefits of these policies may extend beyond the public schools they target. In schooling markets, the education multiplier effect will create positive knock-on effects for private schools.

Third, leaders should consider an entirely different class of policies. These are policies that do not privilege either the public or private sector but acknowledge that both parents and schools face constraints and that alleviating these constraints can lead to significant improvements in both sectors, regardless of the preferences of parents or the cost structures of schools.

Studies by the LEAPS team present two examples of such policies. In the first, the team provided parents and schools with information on the performance of all schools in a village—public and private—through school “report cards.” We found that this intervention improved test scores in both public and private schools and decreased private-school fees. The policy, in this case, pays for itself and has been recognized as a global “great buy” by a team of education experts.

As a second example, in 2020 the LEAPS team provided grants to private schools, but in some villages, we gave the grant money to a single school and in others to all private schools in the village. We found that in the first scenario, the school used the money to upgrade infrastructure and expand enrollment but with no resulting improvement in test scores. However, when all the private schools in a village received a grant, schools expanded enrollment and increased student test scores. These schools anticipated that simultaneous capacity improvements by all the private schools would lead to a price war, driving profits to zero, so they focused largely on test-score improvements to maintain profit margins. In both scenarios, the combination of boosted enrollment and higher fees increased the schools’ profits. These increases were large enough that, had the schools taken the money in the form of loans, they would have been able to repay them at interest rates of 20 to 25 percent or more. Finally, the schools improved even though the grant terms did not explicitly require them to—showing that the market generated the incentives for improvement without additional monitoring and testing by external parties, which in Pakistan has proven to be both costly and difficult.

These interventions leverage the fact that many children in Pakistan and around the globe now live in neighborhoods with multiple public and private schools. In these environments, progress relies on alleviating broader constraints in the education market rather than focusing on specific schools or school types. Moving beyond “public versus private,” we now need policies that support schooling markets, not schools—the entire ecosystem, not just one species.

Jishnu Das is a distinguished professor of public policy at the McCourt School of Public Policy and the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and a Senior Visiting Fellow at the Center for Policy Research in New Delhi, India.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 11, 2023 at 10:42am

-

The education spending multiplier: Evidence from schools in Pakistan

Tahir Andrabi Natalie Bau Jishnu Das Naureen Karachiwalla Asim Ijaz Khwaja / 11 Jun 2023

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/education-spending-multiplier-eviden...

Private schools in Pakistan, as in many other countries, are financed almost entirely through school fees. Therefore, when public schools improve, private schools must also improve or risk losing valuable revenue as parents opt for public schools. This column examines the effect of a public school grants programme in rural Pakistan and estimates the ‘education multiplier’ for the effect of public funding on private sector school quality. The authors find that grants given to public schools increase test scores in both public and private schools as a result of increased competition.

In the past, policymakers worried that there were not enough schools for children in low- and middle-income countries. But today, millions of children in these countries live in villages or neighbourhoods where they can choose from multiple public or private schools. Figure 1, for instance, shows a typical village in the Learning and Educational Achievement in Pakistan Schools (LEAPS) study. The village takes 20 minutes to cross on foot, but has five private and two public schools. The average village in the LEAPS sample has 7.3 schools, and 60 to 70% of the rural population in Punjab (Pakistan’s largest province) lives in such environments. If we include cities, that fraction rises to more than 90%.

That is a big deal for public policy, which has historically failed to account for the relationship between public policy and the private sector in education.

To see why, note that private schools in Pakistan, like in many other countries, are financed almost entirely through school fees, which parents must be willing to pay. Therefore, when public schools improve, private schools must respond, or face the risk of losing valuable revenue as children opt to attend improved public schools. Thus, understanding the total impact of any programme - even those targeted purely to public schools - requires considering its effect on all other schools in the market, not just on the school where the intervention was implemented, as accounting for the total effects can lead to very different conclusions about effectiveness. Our new paper (Andrabi et al. 2023) measures the effect of a public school grants programme in rural Pakistan and estimates the ‘education multiplier’ for the effect of public funding on private sector school quality.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 11, 2023 at 10:43am

-

The education spending multiplier: Evidence from schools in Pakistan

Tahir Andrabi Natalie Bau Jishnu Das Naureen Karachiwalla Asim Ijaz Khwaja / 11 Jun 2023

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/education-spending-multiplier-eviden...

The Evaluation

Our evaluation has three key features: the environment, the intervention, and the data.

Environment: We worked in 80 villages with closed education markets, where 90% of the children in the village attend schools in the village, and 90% of the enrolment in the schools comes from the village itself. Closed markets allow us to trace the full impact of public school improvements on other schools without getting into tricky questions of determining which private schools compete with treated public schools.

Intervention: Our intervention was a grants programme where money was given to public schools for necessary investments determined by a newly constituted school council in collaboration with an NGO. The programme was allocated to randomly selected villages, and the research team had zero contact with the government, both in the targeting of schools within villages and the implementation of the scheme, allowing us to identify the effects of the policy as it would be implemented by the government in practice.

Data: We collected data from all schools in these villages between 2003 and 2011 as part of the LEAPS study. We tested more than 70,000 children, interviewed more than 4,000 school-owners and teachers, and collected detailed information on the households of the tested children. We also gathered information about which schools exited and entered the market over these eight years and how their enrolments changed over this period.

Five years after the programme started in 2006, public schools in treated villages had received an additional PKR 492,020 in funding compared to those in control villages. This amount translates into a 42% increase over the funding that control schools received in this period and 29% of median annual public-school expenditures (inclusive of teacher salaries). Consistent with the new guidelines, we also find that the composition of school councils became more socioeconomically inclusive and representative of the parent body, and the number of school council meetings increased.

Test scores increase in public and private schools

We then show that the programme causally increased aggregate test scores in treated villages by 0.2 standard deviations. This aggregate increase reflects, first, an increase in test scores of 0.2 standard deviations among public schools. Strikingly, through the education multiplier, it also reflects an increase in test scores of 0.2 standard deviations among private schools. Furthermore, among private schools, test score improvements were higher in schools that faced stronger competitive pressures. Consistent with models of ‘horizontal differentiation’, private schools located closer to public schools saw larger test score increases. Consistent with models of ‘vertical differentiation,” private schools located in villages with higher-quality public schools at the beginning of the programme improved the most, even though there was no heterogeneity in the impact of the treatment on public schools themselves by baseline test scores.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 11, 2023 at 10:44am

-

The education spending multiplier: Evidence from schools in Pakistan

Tahir Andrabi Natalie Bau Jishnu Das Naureen Karachiwalla Asim Ijaz Khwaja / 11 Jun 2023

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/education-spending-multiplier-eviden...

Private school fees and their entry or exit into the schooling market are not affected

Interestingly, we do not find evidence of a treatment effect on private school fees, exits (or entries) or market shares - by 2011, the market share of private schools was the same in treatment and control villages. The fact that market share did not change does not mean that parents do not respond to or observe improvements in school quality. Rather, enrolment shares in 2011 are an equilibrium outcome following quality changes in both sectors.

Cost-effectiveness

Using standard methods from the literature (Dhaliwal et al. 2013), we then show that the intervention increased test scores in public schools by 1.18 standard deviations for every US$100 in additional spending. But once we factor in improvement in private schools as well, cost-effectiveness increases by 85% to 2.18 standard deviations for every $100 in additional public funding, putting the programme among a small group of highly cost-effective interventions (see Evans and Yuan 2022). Finally, the education multiplier also had fundamental implications for how programmes should be targeted. We show that regardless of whether the government is interested in maximising test score gains from the programme or is interested both in equity and gains, accounting for the education multiplier changes the optimal geographical targeting and distribution of grants across villages.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 11, 2023 at 10:45am

-

The education spending multiplier: Evidence from schools in Pakistan

Tahir Andrabi Natalie Bau Jishnu Das Naureen Karachiwalla Asim Ijaz Khwaja / 11 Jun 2023

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/education-spending-multiplier-eviden...

Conclusion

Our first main result, that grants to public schools increased test scores, contrasts with an earlier literature where null effects were more common (e.g. Das et. al. 2013, Mbiti et. al. 2019). We may now need to move beyond such ‘grant pessimism’ precisely because we have learned from the previous failures. In contrast to previous grants in India and Zambia, which were offset by parents because they were small, the grants here were much larger and could be used for infrastructure improvements (Das et al. 2013). Indeed, grant size and test score improvements are positively correlated in this programme.

In addition, the schools could use the grants to hire teachers on temporary contracts. Again, this policy reflected what we had learned from prior research, which has consistently shown that teachers hired on temporary contracts may be more effective because they face stronger career incentives (Duflo et al. 2015, Muralidharan and Sundararaman 2013, Bau and Das 2020).

Finally, to avoid the problems of centrally mandated expenditures that are not responsive to local needs as well as potential misuse, schools worked with a reputed NGO and a reconstituted school council to determine investment priorities that were then funded through the grant.

Beyond showing that public school grants can increase test scores, this study demonstrates the existence of a large education multiplier from the public to the private sector. Hundreds of millions of children live in neighbourhoods/villages with substantial school choice, and many of the schools that they can choose from are private schools that survive on school fees. In this highly interconnected world, the idea that there are `programmes for public schools’ and `programmes for private schools’ and that the two can be kept separate is no longer tenable. Failing to account for the effect of public sector interventions on the private sector - ex-ante in the design of the programme and ex-post in its evaluation – leads to less effective interventions and inaccurate evaluations. In our case, restricting the focus to public schools would have led to an entirely different estimate of the programme’s cost effectiveness.

While we show that taking the private sector into account is crucial, spillovers on private schools need not always be positive. Dinerstein and Smith (2021) find that in New York City a public-school improvement programme led to children leaving private schools, and these schools then shutting down. In the Dominican Republic, Nielson et al. (2020) show that a huge school construction programme led to the closure of some private schools, but with quality improvements among the survivors. But across all these studies, the clear message is that the days when public school programmes would have effects only on public schools are over. We need to think of the full schooling environment and not just the part in which we have intervened.

Comment

- ‹ Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- Next ›

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Silicon Valley Pakistani-Americans Among Top Donors to Mamdani Campaign

Omer Hasan and Mohammad Javed are the top donors to Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral campaign in New York City, according to media reports. Both are former executives of Silicon Valley technology firm AppLovin. Born and raised in Silicon Valley, Omer is the son of a Pakistani-American couple who are long-time residents of Silicon Valley, California. …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on September 19, 2025 at 9:00am

Modi's Hindutva: Has BJP's Politics Hurt India's International Image?

The Indian cricket team's crass behavior after defeating the Pakistani team at the Asia Cup 2025 group encounter has raised eyebrows among sports fans around the world. Not only did Suryakumar Yadav, the Indian team captain, refuse to do the customary handshake before and after the match in Dubai but he also made controversial statements linking the match with the recent India-Pakistan conflict. “A few things in life are above sportsman’s spirit ......We stand with all the victims of the …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on September 15, 2025 at 7:00pm — 1 Comment

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network