PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Pakistan is the World's Biggest Importer of Used Clothes

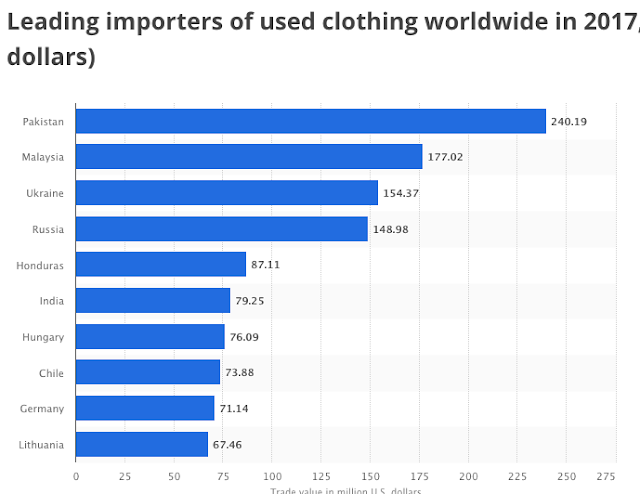

Back in the winter of 1977 when I made preparations to travel to the United States to attend graduate school, my late mother took me to Karachi's "Landa Bazar" to help me pick out imported extra warm second hand clothing. The purchased item appeared to be brand new, especially after dry-cleaning. I would not have survived my first months in New York without the winter coats and jackets and accessories like caps, gloves and boots bought in Karachi, Pakistan. A recent look at the Statista stats portal's 2017 data revealed that Pakistan imported $240 million worth of used clothing making it the world's largest importer in this category.

Landa Bazars in Pakistan:

A Pakistani newspaper headline last week screamed "Sale Of Second Hand Warm Clothes Picks Up In Landa Bazars Hyderabad". Landa Bazars is the name of "flea markets" that specialize in selling used clothes and they do brisk business at the start of each winter. These markets are found in all major cities and cater to middle-class and poor customers looking for moderately priced warm clothing for a couple of weeks of cold weather. Pakistan has a huge domestic textile industry that meets the needs of the people with relatively cotton clothing for the rest of the year. Pakistan is also a big exporter of ready made garments.

The second hand clothing that I used in my first few months in the United States in the winter of 1977-78 was purchased at Karachi's Landa Bazar. The purchased item appeared to be brand new, especially after dry-cleaning. In the next winter season when a new batch of Indian and Pakistani students came to the campus, I passed these on to those who came unprepared my heavy winter coat and jacket.

Landa Bazar (Flea Market) in Pakistan |

Second Hand Clothing Trade:

Used clothing exports added up to $3.67 billion in 2016, according to MIT's Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC).

The top exporters of Used Clothing included the United States ($648M), Germany ($371M), the United Kingdom ($348M), China ($219M) and South Korea ($214M). The top importers in 2016 were Pakistan ($206M), Ukraine ($166M), Kenya ($131M), Malaysia ($129M) and Ghana ($126M).

Second Hand Clothing in United States:

Americans donate used clothes, including slightly used clothes hanging in their closets, to charities such as Goodwill and Salvation Army. These donations pick up during holidays when people clear out their closets to make room for new purchases. American tax law encourages such charitable donation which are tax-deductible. Some of these used clothes are sold by charities at stores like Goodwill stores and Salvation Army thrift stores and the rest are exported.

America's secondhand clothing business has been export-oriented since the introduction of mass-produced garments. And by one estimate, used clothing is now the United States’ number one export by volume, according to Slate.com.

Summary:

Global trade of secondhand clothing is near $4 billion a year. United States is the biggest exporter and Pakistan is the biggest importer of used clothing. The second hand clothing that I used in my first few months in the United States in the winter of 1977-78 was purchased at Karachi's Landa Bazar. The purchased item appeared to be brand new, especially after dry-cleaning. In the next winter season when a new batch of Indian and Pakistani students came to the campus, I passed these on to those who came unprepared my heavy winter coat and jacket. Landa Bazars is the name of "flea markets" that specialize in selling used clothes and they do brisk business at the start of each winter. These markets are found in all major cities and cater to middle-class and poor customers looking for moderately priced warm clothing for a couple of weeks of cold weather. Pakistan has a huge domestic textile industry that meets the needs of the people with relatively cotton clothing for the rest of the year.

Related Links:

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 27, 2020 at 10:46am

-

Poshmark IPO Speaks Volumes About Fashion’s Future

https://sourcingjournal.com/topics/retail/poshmark-ipo-fashion-resa...

Poshmark filed its prospectus Thursday for an initial public offering after finally turning a profit this year. The move follows secondhand rival ThredUp’s October IPO filing, underscoring the sky’s-the-limit growth potential for the booming fashion resale market, fueled in large part by eco-conscious millennial and Gen Z consumers whose full spending power has yet to be seen.

Unlike ThredUp or luxury peer The RealReal, similarly Bay Area-based Poshmark courts individual buyers and sellers to its online fashion marketplace for secondhand goods, allowing them to transact directly with each other for a small fee. Since launching in 2011, the company says it has attracted more than 70 million users and sold more than 130 million items, pushing cumulative gross merchandise volume (GMV) to $4 billion. Active users last year spent an average of 27 minutes on its site, connecting with each other through 20.5 billion social interactions.

“Secondhand and resale also continue to grow as consumers, particularly younger generations, adopt efforts to reduce overall consumption and support a more sustainable economy,” Poshmark said, citing its Social Commerce Report, executed with Zogby Analytics, stating that 16 percent of the Gen Z consumer closet is secondhand, versus 10 percent for baby boomers.

“According to that report, 72% of our U.S. users often consider an item’s resale value before purchasing, and that when unable to return an item online, 93% of our U.S. users would sell it online,” it added. Plus, the “online U.S. resale market for apparel and footwear is estimated to have been $7 billion in 2019 and is expected to grow to an estimated $26 billion in 2023,” it said, pointing to research it commissioned with GlobalData earlier this year.

Although the coronavirus pandemic affected Poshmark’s GMV, which measures the total dollar value of merchandise sold online, the metric gained ground as buyers and sellers resumed transactions following the initial outbreak. This year, GMV growth for the quarter ended March 31 was 9 percent but rebounded to 42 percent for the second quarter June 30. While it has benefited from stay-at-home orders as consumers shifted their purchasing to online, Poshmark cautioned that the pandemic “has impacted, and will continue to impact, our business.”

For its IPO, Poshmark plans to sell $100 million worth of shares, the typical placeholder by companies figuring out filing fees. Shares will trade on the Nasdaq under the symbol “POSH.”

The company said it posted its first quarter of profitability for the period ended June 30, which saw net income of $8.1 million, or 45 cents a share. For the nine months, revenue rose 28.1 percent to $192.8 million from $150.5 million, while it posted a net profit of $20.9 million, against a net loss of $33.9 million in the year-ago period. For the year ended Dec. 31, 2019, the company widened its net loss to $48.69 million from the year ago net loss of $14.5 million.

Poshmark charges a fee of 20 percent of the final price for sales over $15, or a flat rate of $2.95 for sales under $15.

As of Sept. 30, the peer-to-peer platform featured “over 201 million secondhand and new items for sale across 9,431 brands,” with “31.7 million active users, 6.2 million active buyers and 4.5 million active sellers,” it said.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 27, 2020 at 10:46am

-

A massive force is reshaping the fashion industry: secondhand clothing. According to a new report, the U.S. secondhand clothing market is projected to more than triple in value in the next 10 years – from US$28 billion in 2019 to US$80 billion in 2029 – in a U.S. market currently worth $379 billion. In 2019, secondhand clothing expanded 21 times faster than conventional apparel retail did.

https://theconversation.com/secondhand-clothing-sales-are-booming-a...

Even more transformative is secondhand clothing’s potential to dramatically alter the prominence of fast fashion – a business model characterized by cheap and disposable clothing that emerged in the early 2000s, epitomized by brands like H&M and Zara. Fast fashion grew exponentially over the next two decades, significantly altering the fashion landscape by producing more clothing, distributing it faster and encouraging consumers to buy in excess with low prices.

While fast fashion is expected to continue to grow 20% in the next 10 years, secondhand fashion is poised to grow 185%.

As researchers who study clothing consumption and sustainability, we think the secondhand clothing trend has the potential to reshape the fashion industry and mitigate the industry’s detrimental environmental impact on the planet.

The next big thing

The secondhand clothing market is composed of two major categories, thrift stores and resale platforms. But it’s the latter that has largely fueled the recent boom. Secondhand clothing has long been perceived as worn out and tainted, mainly sought by bargain or treasure hunters. However, this perception has changed, and now many consumers consider secondhand clothing to be of identical or even superior quality to unworn clothing. A trend of “fashion flipping” – or buying secondhand clothes and reselling them – has also emerged, particularly among young consumers.

Thanks to growing consumer demand and new digital platforms like Tradesy and Poshmark that facilitate peer-to-peer exchange of everyday clothing, the digital resale market is quickly becoming the next big thing in the fashion industry.

The market for secondhand luxury goods is also substantial. Retailers like The RealReal or the Vestiaire Collective provide a digital marketplace for authenticated luxury consignment, where people buy and sell designer labels such as Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Hermès. The market value of this sector reached $2 billion in 2019.

The secondhand clothing trend also appears to be driven by affordability, especially now, during the COVID-19 economic crisis. Consumers have not only reduced their consumption of nonessential items like clothing, but are buying more quality garments over cheap, disposable attire.

For clothing resellers, the ongoing economic contraction combined with the increased interest in sustainability has proven to be a winning combination.

More mindful consumers?

The fashion industry has long been associated with social and environmental problems, ranging from poor treatment of garment workers to pollution and waste generated by clothing production.

----------

High-quality clothing traded in the secondhand marketplace also retains its value over time, unlike cheaper fast-fashion products. Thus, buying a high-quality secondhand garment instead of a new one is theoretically an environmental win. But some critics argue the secondhand marketplace actually encourages excess consumption by expanding access to cheap clothing.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 21, 2021 at 5:56pm

-

Galaxy Rags ,Boys Clothing ,Pakistan

https://www.company-list.org/galaxy_rags.html

Company Introduction

WE ARE A GRADING & SORTING COMPANY OF USED CLOTHING & SHOESBASED IN KARACHI EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE IN PAKISTAN.WE ARE IMPORTING ALL OUR MIXED RAGS FROM USA AND THENPROCESSING AT OUR FACTORY THEN SHIPPING TO AFRICA.ALL ENQUIRIES ARE MOST WELCOME. WE ARE INTERESTED IN COVERING MOREAFRIACN MARKETS.

https://youtu.be/AUzlEhVbt3o

------------

Because of coronavirus, Europe is drowning in second-hand clothes

There’s pressure on the EU to help stop lockdown cast-offs from going to waste.

https://www.politico.eu/article/coronavirus-europe-drowning-second-...

Selling clothing that is reusable abroad often helps sorting companies break even. Of the 16 million tons of waste the EU textile industry generates per year, globally only 1 percent is recycled back into new garments — 50 percent is shipped to poorer countries, where it’s sold on local markets.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, exporters have cut their prices in a bid to shift stock. “The risks right now are much higher than the opportunities,” said Martin Böschen, head of the textiles division of the Bureau of International Recycling.

While recent months had brought some improvement in demand, prices are still “15 to 25 percent lower than before COVID-19,” said Böschen.

Gebetex exports around 40 percent of its reusable clothes and textiles outside the EU. “Regardless of the continents, the border closures simply blocked exports,” said Bourgeois, citing particular difficulties for shipments to Pakistan and India.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 25, 2023 at 5:40pm

-

The year of the landa bazar

One trader’s loss is another’s profit

https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2023/04/21/the-year-of-the-land...

It is a classic example of the economic concept of arbitrage, in which you buy the same product in one market at a lower price and sell it in another market at a significantly higher price. But then why is this year going to be better for the landa? Normally, the thrifted clothes that arrive in Pakistan are so cheap that merchants from other countries such as Turkey, Afghanistan, and India buy these clothes from Pakistan at a slightly marked up price.

---

The landa arbitrage market

It is a pretty linear system. Charities, churches, and community centres collect clothes that people give away in foreign countries. The clothes are mostly hand-me-downs. As we mentioned earlier, charitable organisations do not have the time or the resources to sort and deliver these clothes to people that need them. Instead, they pack them up into huge bundles that weigh up to 60Kgs and sell them.

Who buys these bundles? There are retailers that have made a business out of hand-me-down clothing. In the UK, for example, there are enterprising Pakistani expats that store the clothes in warehouses. The first thing they do is open these bundles up and sort the clothes by categories. Pants on one end, shirts on the other, shoes in a different corner and so on and so forth. After this, each pile is sorted for quality, and by the end you have different kinds of items categorised by quality, age, and by brand. Out of this, the best quality products are sent off to thrift stores within the country. So if the warehouse is in Bradford, England — the best clothes will go to thrift stores in Bradford where they will fetch the best price.

The rest of the clothes are then exported. They are fumigated (this is where the infamous ‘landa smell’ comes from), once again bundled up (this time pre-sorted) and then shipped off to third-world countries. The market for this is massive, and Pakistan is one of the major importers of these clothes. According to a 2015 article in The Guardian, most donated clothes are exported overseas. A massive 351m kilograms of clothes (equivalent to 2.9bn T-shirts) are traded annually from Britain alone. The top five destinations are Poland, Ghana, Ukraine, Benin, and yes, Pakistan. Low-income families then shop at these markets, where winter clothes are in high-demand.

The report estimated that globally the wholesale used clothing trade is valued at more than £2.8 billion. It is a textbook example of arbitrage. Donated clothes are sold dirt cheap in developed countries, but since they are not readily available to low-income families in the third world, their value is higher in that market. Arbitrage is essentially a risk-free way of making money by exploiting the difference between the price of a given good on two different markets. In fact, an example of arbitrage often cited in textbooks is that of vintage clothing, and how a given set of old clothes might cost $50 at a thrift store or an auction, but at a vintage boutique or online, fashion conscious customers might pay $500 for the same clothes.

Pakistan plays a significant role in this arbitrage, and in the past few years the demand for these clothes has only increased. According to data released by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), during the last fiscal year (FY 2020-21), the import of used clothing increased by 90 per cent to $309.56 million and it weighed 732,623 metric tons. The year before that, there was an increase of 83.43 percent in terms of price. Pakistan imported 186,299 metric tons of pre-used garments during the first two months of the FY 2021-22 (July-August), which makes up for an increase of 283 per cent over the same period of last year, which translates to a spending of $79 million.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 1, 2023 at 4:06pm

-

Fashion cycles are moving faster than ever. A Quartz article in December revealed how fashion brands like Zara, Gap and Adidas are churning out new styles more frequently, a trend dubbed "fast fashion" by many in the industry. The clothes that are mass-produced also become more affordable, thus attracting consumers to buy more.

"It used to be four seasons in a year; now it may be up to 11 or 15 or more," says Tasha Lewis, a professor at Cornell University's Department of Fiber Science and Apparel Design.

The top fast fashion retailers grew 9.7 percent per year over the last five years, topping the 6.8 percent of growth of traditional apparel companies, according to financial holding company CIT.

Fashion is big business. Estimates vary, but one report puts the global industry at $1.2 trillion, with more than $250 billion spent in the U.S. alone. In 2014, the average household spent an average $1,786 on apparel and related services.

https://www.npr.org/2016/04/08/473513620/what-happens-when-fashion-...

--------------

See the World's Unsold Clothing in a Huge Desert Pileup

A satellite image shows where tons of fast-fashion items are heaped in a clothing graveyard in the Atacama Desert

https://gizmodo.com/clothing-pile-chile-atacama-desert-satellite-im...

The world’s fast-fashion addiction is wrecking the planet. It’s also contributing to an enormous and growing pile of clothing that is sitting in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

SkyFi, a company that provides access to satellite imagery, recently shared a striking view of the Atacama Desert. The company explained in a blog post last week that members of its Discord channel had helped find the coordinates for the growing graveyard of trashed garments.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 23, 2023 at 7:56pm

-

These entrepreneurs in Pakistan are moving the country’s massive secondhand clothes market online

https://www.fastcompany.com/90956788/pakistan-economy-swag-kicks-se...

With the country in the middle of a historic economic crisis, secondhand sellers are seeing big business as they build an e-commerce market.

Iqra Anwar, a resident of Lahore, the second largest city of Pakistan is a frequent thrift shopper. Though her favorite brands—American fast-fashion staples like H&M, Zara, and Victoria’s Secret—don’t have outposts in the city, she still manages to buy their preloved versions at dirt cheap prices by thrifting.

“I got tank tops for 200 rupees (66 cents), which I would have otherwise gotten for 2000 rupees or for even more than 3000 rupees (around $10),” she says about her latest purchase.

The 22-year-old university student wanted stylish and branded clothes on a budget while she attended her classes. She’s not alone. With Pakistan in the midst of its worst-ever economic crisis and its currency severely devalued alongside record-high inflation (annual inflation was at 38% in May), she says she’s seeing more people are turning to affordable, secondhand clothing.

“Now, a lot of my friends who are from elite backgrounds ask me to go thrifting with them because the economy has affected anyone and everyone,” Anwar says. “They could buy [new] Shein and Zara products two years ago, but now they cannot.” Shoppers like Anwar also recognize the climate impact of getting as much wear out of fast-fashion items. “Because of fast fashion, there are landfills with clothes that people have only worn once,” she says. “It has become more of a social good thing to thrift.”

Whatever their reasons, shoppers in Pakistan have no shortage of pre-worn clothes. In 2021, Pakistan imported $180M of secondhand clothing, becoming the second-largest importer of pre-owned clothing in the world. Secondhand clothing was mainly imported from China, United States, and Canada and became the 69th most imported product in Pakistan. The country has long had a booming secondhand market, with clothing being sold at its “landa bazaars.” As the purchasing power of everyday Pakistani shoppers has been diminished, these bazaars—and a growing roster of online clothing sellers—have become resources for keeping wardrobes across the country full.

Until relatively recently, online sale of pre-owned clothing in Pakistan has been negligible. One of the earliest marketplaces to debut online was Swag Kicks, founded by self-described sneakerhead Nofal Khan who, as a child, would rely on his relatives visiting from Western countries to get him high-end branded sneakers that were unavailable in Pakistan. That is, until he discovered warehouses housing imported secondhand shoes.

“There were Jordans, Onitsuka Tiger, Nike Air Force 1s . . . the kind of shoes that I would never get in Pakistan,”Khan says. “When I used to wear those shoes to university, a lot of people would ask me where I got them from. That’s when I realized . . . they didn’t have access to quality shoes.” This made him realize the potential of this business and pushed him to start an online marketplace.

Earlier this year, Swag Kicks raised $1.2 million in a seed funding round led by i2i Ventures, joined by Techstars Toronto, SOSV Orbit, and local angel investors. This money, Nofal says, is being invested into automating the inventory process, scaling existing technology and improving disinfection and sanitization of clothes.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 23, 2023 at 7:57pm

-

These entrepreneurs in Pakistan are moving the country’s massive secondhand clothes market online

https://www.fastcompany.com/90956788/pakistan-economy-swag-kicks-se...

Digitalizing this market makes sense for Pakistan: the country has a huge young population with around 64% of the population under 30 years old. Internet penetration stood at 36.7% at the start of 2023, giving easy access to online stores.

“Young people are looking at global trends on Instagram and TikTok. They follow Western celebrities, and they know which shoes are famous, but they don’t have access to those brands,” Khan says. “We are bridging the gap by bringing the best of sneaker culture to Pakistan . . . and listing them on our website for a fraction of the cost of what their brand-new counterparts would cost.”

Digitizing has also given the online marketplace an upper hand over the existing physical landa bazaars. These markets are crowded, located in far-flung areas and often considered unsafe for women. And physical stores limit inventory, something Khan says is an advantage to selling online. “At any given point, we have 25,000 different types of shoes,” he says. “Physical stores can hold a limited amount of inventory.”

Through trending reels and captivating visuals, the startup aims to attract a younger audience on social media. Its TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook pages boast a combined reach of 135,000 followers.

Instagram in particular is where a growing number of sellers are courting younger shoppers like Iqra—and its user demographics are on their side. People, aged 18 to 24, are Instagram’s largest user group in Pakistan, which has 13 million users nationwide.

Sellers like Zari Faisal are using this to their advantage, using the platform as a storefront for pre-owned clothing. Faisal’s Instagram account, Thrifty Preloved, started in 2019 as an experiment, and has grown to have more than 40,000 followers who place an average of 300 orders per week—fulfilled by more than 20 employees. Faisal adds five to six new products per day, and offers delivery to nationwide—including smaller cities like Lodhran and Bahawalpur.

More than just e-commerce destinations, Instagram accounts also serve as resources for potential customers—Faisal says she has helped suggest outfits for a follower asking about what they might wear to a business presentation. “Our team got really involved,” Faisal says. “To be that sort of buddy that someone comes to for fashion advice is something that we really enjoy doing.”

Faisal sees continued growth in thrift shopping as Pakistan’s economic turmoil continues—and says she’s playing a role in keeping fashion accessible. “A generic Zara piece would cost around 13000 Pakistani rupees (roughly $43.66) minimum. . . . We’re able to provide Zara pieces, under, like you know, 2500 rupees ($8.25),” she says. “We are getting access to [good quality] products at pricing that none of us would be able to afford in Pakistan right now.”

Comment

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Trump Administration Seeks Pakistan's Help For Promoting “Durable Peace Between Israel and Iran”

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio called Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif to discuss promoting “a durable peace between Israel and Iran,” the State Department said in a statement, according to Reuters. Both leaders "agreed to continue working together to strengthen Pakistan-US relations, particularly to increase trade", said a statement released by the Pakistan government.…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on June 27, 2025 at 8:30pm — 4 Comments

Clean Energy Revolution: Soaring Solar Energy Battery Storage in Pakistan

Pakistan imported an estimated 1.25 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of lithium-ion battery packs in 2024 and another 400 megawatt-hours (MWh) in the first two months of 2025, according to a research report by the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). The report projects these imports to reach 8.75 gigawatt-hours (GWh) by 2030. Using …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on June 14, 2025 at 10:30am — 3 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network