PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Is Pakistan's Social Sector Making Progress?

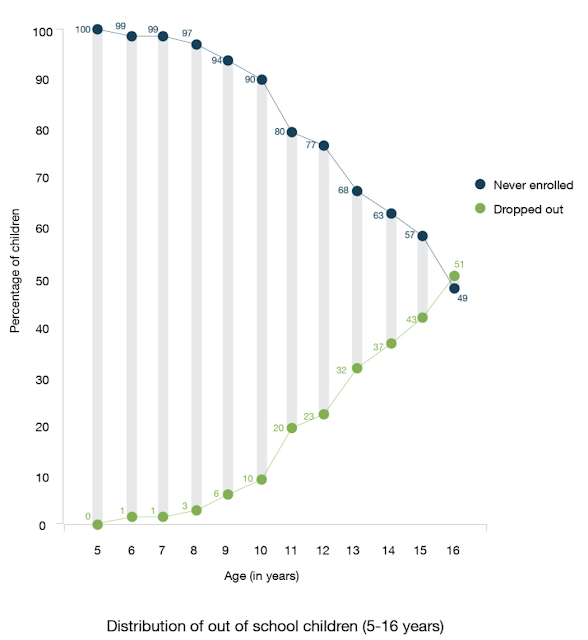

If you read Pakistan media headlines and donation-seeking NGOs and activists' reports these days, you'd conclude that the social sector situation is entirely hopeless. However, if you look at children's education and health trend lines based on data from credible international sources, you would feel a sense of optimism. This exercise gives new meaning to what former US President Bill Clinton has said: Follow the trend lines, not the headlines. Unlike the alarming headlines, the trend lines in Pakistan show rising school enrollment rates and declining infant mortality rates.

|

| Pakistan Children 5-16 In-Out of School. Source: Pak Alliance For M... |

|

| Source: World Bank Education Statistics |

|

| Pakistan Child Mortality Rates. Source: PDHS 2017-18 |

During the 5 years immediately preceding the survey, the infant mortality rate (IMR) was 62 deaths per 1,000 live births. The child mortality rate was 13 deaths per 1,000 children surviving to age 12 months, while the overall under-5 mortality rate was 74 deaths per 1,000 live births. Eighty-four percent of all deaths among children under age 5 in Pakistan take place before a child’s first birthday, with 57% occurring during the first month of life (42 deaths per 1,000 live births).

|

| Pakistan Human Development Trajectory 1990-2018.Source: Pakistan HD... |

Human Development Ranking:

It appears that improvements in education and health care indicators in Pakistan are slower than other countries in South Asia region. Pakistan's human development ranking plunged to 150 in 2018, down from 149 in 2017.

| Expected Years of Schooling in Pakistan by Province |

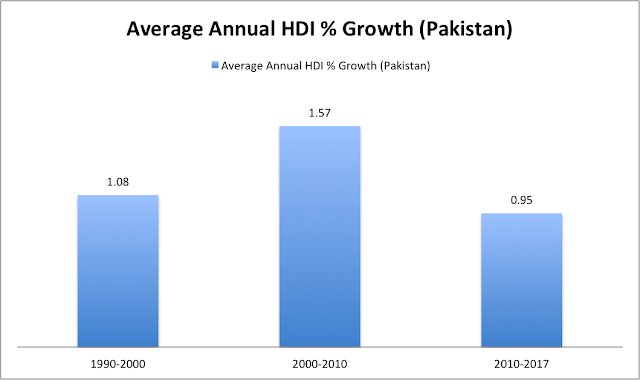

There was a noticeable acceleration of human development in #Pakistan during Musharraf years. Pakistan HDI rose faster in 2000-2008 than in periods before and after. Pakistanis' income, education and life expectancy also rose faster than Bangladeshis' and Indians' in 2000-2008.

Now Pakistan is worse than Bangladesh at 136, India at 130 and Nepal at 149. The decade of democracy under Pakistan People's Party and Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) has produced the slowest annual human development growth rate in the last 30 years. The fastest growth in Pakistan human development was seen in 2000-2010, a decade dominated by President Musharraf's rule, according to the latest Human Development Report 2018.

UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI) represents human progress in one indicator that combines information on people’s health, education and income.

|

| Pakistan's Human Development Growth Rate By Decades. Source: HDR 2018 |

Pakistan saw average annual HDI (Human Development Index) growth rate of 1.08% in 1990-2000, 1.57% in 2000-2010 and 0.95% in 2010-2017, according to Human Development Indices and Indicators 2018 Statistical Update. The fastest growth in Pakistan human development was seen in 2000-2010, a decade dominated by President Musharraf's rule, according to the latest Human Development Report 2018.

|

| Pakistan Human Development Growth 1990-2018. Source: Pakistan HDR 2019 |

Pakistan@100: Shaping the Future:

Pakistani leaders should heed the recommendations of a recent report by the World Bank titled "Pakistan@100: Shaping the Future" regarding investments in the people. Here's a key excerpt of the World Bank report:

"Pakistan’s greatest asset is its people – a young population of 208 million. This large population can transform into a demographic dividend that drives economic growth. To achieve that, Pakistan must act fast and strategically to: i) manage population growth and improve maternal health, ii) improve early childhood development, focusing on nutrition and health, and iii) boost spending on education and skills for all, according to the report".

|

| Pakistani Children 5-16 Currently Enrolled. Source: Pak Alliance Fo... |

Summary:

The state of Pakistan's social sector is not as dire as the headlines suggest. There's reason for optimism. Key indicators show that education and health care in Pakistan are improving but such improvements are slower than in other countries in South Asia region. Pakistan's human development ranking plunged to 150 in 2018, down from 149 in 2017. It is worse than Bangladesh at 136, India at 130 and Nepal at 149. The decade of democracy under Pakistan People's Party and Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) has produced the slowest annual human development growth rate in the last 30 years. The fastest growth in Pakistan human development was seen in 2000-2010, a decade dominated by President Musharraf's rule, according to the latest Human Development Report 2018. One of the biggest challenges facing the PTI government led by Prime Minister Imran Khan is to significantly accelerate human development rates in Pakistan.

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan's Expected Demographic Dividend

Can Imran Khan Lead Pakistan to the Next Level?

Democracy vs Dictatorship in Pakistan

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

Panama Leaks in Pakistan

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 6, 2023 at 5:13pm

-

https://www.educationnext.org/no-school-stands-alone-how-market-dyn...

Jishnu Das

Parents’ Choices

The relevant question, then, is not whether private schools are more effective. The questions are: How well are parents equipped to discern quality in a school—public or private—and choose the best one for their children? And can policy decisions affect these choices?

As to the first question, the team found that parents choosing private schools appear to recognize and reward high quality. Consequently, in the LEAPS villages, private schools with higher value-added are able to charge higher fees and see their market share increase over time. In contrast, parents choosing public schools either have a harder time gauging the school’s value-added or are less quality-sensitive in their choices. This is particularly concerning in the case of students enrolled in very poorly performing public schools where after five years of schooling they may not be able to read simple words or add two single-digit numbers.

Given that parents who opt for public schools appear to be less sensitive to quality, one reform instrument often supported by policymakers is the school voucher, whereby public money follows the child to the family’s school of choice. The idea is that making private schools “free” for families will allow children to leave poorly performing public schools in favor of higher-quality private schools. This strategy assumes that parents, when choosing among schools, place significant weight on the cost of the school, manifest in its fees. What’s more, one may reasonably expect that such “fee sensitivity” will be higher in low-income countries and among low-income families. Yet a 2022 analysis of the LEAPS villages showed that a 10 percent decline in private-school fees increased private-school enrollment by 2.7 percent for girls and 1 percent for boys. From these data we estimated that even a subsidy that made private schools totally free would decrease public-school enrollment by only 12.7 and 5.3 percentage points for girls and boys, respectively. This implies that most of the subsidy, rather than going to children who are leaving public schools, would be captured by children who would have enrolled in private schools even without the tuition aid. Further, most of the children induced to change schools under the policy may come from high- rather than low-performing public schools, limiting any test-score gains one might expect.

One alternative to trying to move children out of poorly performing public schools is to focus on improving those schools. A LEAPS experiment that my co-authors and I published in 2023 evaluated a program that allocated grants to public schools in villages randomly chosen from the LEAPS sample. We found that, four years after the program started, test scores were 0.2 standard deviations higher in public schools in villages that received funds than in public schools in villages that did not. In addition, we observed an “education multiplier” effect: test scores were also 0.2 standard deviations higher in private schools located in grant-receiving villages. This effect echoes an economic phenomenon that often occurs in industry—that is, when low-quality firms improve, higher-quality firms tend to increase their quality even further to protect their market share. In the LEAPS villages, the private schools that improved were those that faced greater competition, either by being physically closer to a public school or by being located in a village where public schools were of relatively high quality at the start of the program. The same was true of private schools in villages where the grants to the public schools were larger.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 6, 2023 at 5:13pm

-

https://www.educationnext.org/no-school-stands-alone-how-market-dyn...

Jishnu Das

The education multiplier effect increases the cost-effectiveness of the grant program by 85 percent, putting it among the top ranks of education interventions in low-income countries that have been subject to formal evaluation. But beyond that, accounting for private-school responses also changed the optimal targeting of the policy. For instance, our analysis shows that if policymakers consider test-score increases in public schools only, a policy that divides resources equally across villages also maximizes test-score gains; there is apparently no trade-off between equity and effectiveness. Once private-school responses are considered, however, equal division of resources exacerbates existing inequalities in learning among villages. This implies that a government that values equity should distribute more resources to villages with poorly performing public schools.

Implications for Policymaking

With 90 percent of Pakistani children living in neighborhoods with multiple public and private schools, the days when government could formulate policies that affected only public schools are long gone. The same is true of many other low-income countries where parents also have significant school choice, ranging from Chile to India. Every policy will have an impact on both public and private schools, even if a policy only targets public schools. Policymakers can choose to ignore these additional effects, but to do so is to miscalculate the policy’s full impact. Our studies are still too premature to help factor parental and private-school responses into the design of policy. A key insight from the LEAPS research is that there is significant variation among schools in terms of performance and among parents in terms of their preferences for quality. A policy to improve public schools can lead to an education multiplier effect in one context but cause private schools to exit in another. A broad understanding of the dynamics of education markets, such as parents placing a very heavy weight on physical distance to school in their choices, can shed some light on this variation. Yet the data requirements to make detailed predictions about how policies will play out in specific settings may be too onerous, at least for now.

How then to proceed? Three broad principles are emerging from the LEAPS project.

First, there is little evidence that parents choosing to send their children to private schools in low-income countries are being fooled or hoodwinked into receiving a substandard education. On the contrary, the parents choosing private schools seem to be more informed and better able to reward school quality. The bigger problem is the substantial population of children enrolled in very low-performing public schools, even when there are better public schools nearby. Unfortunately, policies that seek to move children from public to private schools by means of vouchers may end up spending a lot of money on children who were already going to private schools. What’s more, the test-score gains from such policies may be limited if most of the children who do switch from a public to a private school come from higher-performing public schools. Indeed, a 2022 study by Mauricio Romero and Abhijeet Singh showed that both of these dynamics play out in India’s Right to Education Act, which established one of the world’s largest voucher schemes. Subsidizing private schools in a way that consistently improves test scores by moving children out of low-performing public schools remains an elusive goal.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 6, 2023 at 5:14pm

-

https://www.educationnext.org/no-school-stands-alone-how-market-dyn...

Jishnu Das

If we cannot move children out of low-performing public schools, the alternative is to improve those schools. The second principle, then, is that governments should maintain a focus on improving the quality of public schools. Results of the first generation of efforts to do so in low-income countries were mixed at best, but studies of newer reform efforts that emphasize improved pedagogy, incentives, teacher recruitment and training, and school grants are all showing positive results. A 2021 study by Alex Eble and colleagues, for instance, showed dramatic improvements in test scores in The Gambia with an intervention that used a variety of strategies: hiring teachers on temporary contracts, making changes in pedagogy, monitoring teachers, and giving them regular feedback. Again, the benefits of these policies may extend beyond the public schools they target. In schooling markets, the education multiplier effect will create positive knock-on effects for private schools.

Third, leaders should consider an entirely different class of policies. These are policies that do not privilege either the public or private sector but acknowledge that both parents and schools face constraints and that alleviating these constraints can lead to significant improvements in both sectors, regardless of the preferences of parents or the cost structures of schools.

Studies by the LEAPS team present two examples of such policies. In the first, the team provided parents and schools with information on the performance of all schools in a village—public and private—through school “report cards.” We found that this intervention improved test scores in both public and private schools and decreased private-school fees. The policy, in this case, pays for itself and has been recognized as a global “great buy” by a team of education experts.

As a second example, in 2020 the LEAPS team provided grants to private schools, but in some villages, we gave the grant money to a single school and in others to all private schools in the village. We found that in the first scenario, the school used the money to upgrade infrastructure and expand enrollment but with no resulting improvement in test scores. However, when all the private schools in a village received a grant, schools expanded enrollment and increased student test scores. These schools anticipated that simultaneous capacity improvements by all the private schools would lead to a price war, driving profits to zero, so they focused largely on test-score improvements to maintain profit margins. In both scenarios, the combination of boosted enrollment and higher fees increased the schools’ profits. These increases were large enough that, had the schools taken the money in the form of loans, they would have been able to repay them at interest rates of 20 to 25 percent or more. Finally, the schools improved even though the grant terms did not explicitly require them to—showing that the market generated the incentives for improvement without additional monitoring and testing by external parties, which in Pakistan has proven to be both costly and difficult.

These interventions leverage the fact that many children in Pakistan and around the globe now live in neighborhoods with multiple public and private schools. In these environments, progress relies on alleviating broader constraints in the education market rather than focusing on specific schools or school types. Moving beyond “public versus private,” we now need policies that support schooling markets, not schools—the entire ecosystem, not just one species.

Jishnu Das is a distinguished professor of public policy at the McCourt School of Public Policy and the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and a Senior Visiting Fellow at the Center for Policy Research in New Delhi, India.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 7, 2023 at 7:06pm

-

Chinese companies help in improving social sector

https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/1086783-chinese-companies-help-in-...

Islamabad: Chinese companies have enhanced their role in social development of Pakistan, while addressing the country’s economic and development issues. The companies are an integral part of CPEC. They are the torch bearer of this flagship project of BRI. They are not only helping Pakistan overcome its infrastructure problems but also investing in social development, skills, and environmental protection in Pakistan. All Chinese companies are investing in social development, but only a few have been selected for discussion, a report carried by Gwadar Pro. The Chinese companies not only helped to create thousands of jobs but also invested in building the capacity of hundreds of engineers and staff members.

According to available data, Huaneng Shandong Rui Group, which built the Sahiwal coal power invested in 622 employees for building their capacity and sharpen their skills. Further segregation of data shows that 245 engineers were trained following the need for required skills at plants. Port Qasim also contributed to building the capacity of engineers and staff members. Data shows that 2,600 employees benefited from the capacity-building and skill development opportunities offered by the Port Qasim plant. It trained 600 engineers and 2,000 general staff members.

It is a huge number, especially in the engineering category. It will help Pakistan; as Pakistan has a shortage of qualified and trained engineers. These companies also assisted Pakistan during floods and COVID-19. Second, the Chinese Overseas Port Holding Company (COPHC) is another Chines company, which is investing in social development. The major contribution of COPHC is in the sectors of education, waste management, environmental protection, and the provision of food.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 13, 2023 at 7:06pm

-

Bilal I Gilani

@bilalgilani

Literacy rate by age

Alhamdulilah the younger generation is significantly more literate than older generation

Our literacy rate ( which is calculated on 15+ age group) is going to rise slowly as it has older cohorts in large numbers

Literacy is not end all but it's a start

https://twitter.com/bilalgilani/status/1679408985613676545?s=20

(Bar graph shows literacy rate is 75% for 10-14 age group, 73% for 15-19 and 69% for 20-24....going down to 51% for 40-44 and 34% for 60-64 age group)

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 21, 2024 at 9:08pm

-

Alexa, Google Home and Smartphones Could Make Illiteracy Unimportant - Newsweek

https://www.newsweek.com/2017/09/22/alexa-google-home-smart-phones-...

In a speech-processing world, illiteracy no longer has to be a barrier to a decent life. Google is aggressively adding languages from developing nations because it sees a path to consumers it could never before touch: the 781 million adults who can't read or write. By just speaking into a cheap phone, this swath of the population could do basic things like sign up for social services, get a bank account or at least watch cat videos.

The technology will affect things in odd, small ways too. One example: At a conference not long ago, I listened to the head of Amazon Music, Steve Boom, talk about the impact Alexa will have on the industry. New bands are starting to realize they must have a name people can pronounce, unlike MGMT or Chvrches. When I walked over to my Alexa and asked it to play "Chu-ver-ches," it gave up and played "Pulling Muscles From the Shell" by Squeeze.

In fact, as good as the technology is today, it still has a lot to learn about context. I asked Alexa, "What is 'two turntables and a microphone'?" Instead of replying with anything about Beck, she just said, "Hmm, I'm not sure." But at least she didn't point me to the nearest ice cream cone.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on February 28, 2025 at 8:11pm

-

Education in Pakistan: Not good, but maybe good enough - Profit by Pakistan Today

https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2024/08/05/education-in-pakista...

Not waiting for government favours

While part of this progress is certainly driven by improvements to the government’s own infrastructure, measured purely by proportion of the increase in student enrollment, the private sector has contributed just under 75% of the total growth in enrollment between 2009 and 2022, according to enrollment estimates published in the Pakistan Education Statistics reports published by the Pakistan Institute of Education. The public sector accounts for the remaining 25%.

In other words, Pakistanis are not waiting around for the government to fix the schools (even though the government is making some progress on that front). They are simply going ahead and paying for private schools themselves as soon as they have the ability to pay.

This phenomenon helps explain why the fastest progress in terms of increasing literacy happened in the decade after Pakistan’s dependency ratios – the ratio of prime working age adults to the number of children under the age of 15 and retirees over the age of 65 – peaked.

The dependency ratio peaked in 1995, and that year also represented the an inflection point in literacy improvements: for every year after that, the 10-year progress towards improving literacy kept on rising at a rising pace (the second differential was positive) for the next decade.

What does that mean? It means that once families started to find that they had a bit more spare cash to spend (with dependency ratios declining after 1995), they started investing that spare cash into private school fees for their children, especially in urban areas, and especially in the urban areas they did so at nearly identical rates for their sons and daughters.

Having spent the lead up to 1995 being increasingly cash strapped, the first thing that Pakistani families did when the pressure on their cash flows eased a bit was to invest in the future economic productivity of their households by educating their children. And in perhaps a scathing indictment of how bad the public schools were, they did so through private schools even when public schools were available in their areas.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 14, 2025 at 8:37pm

-

Gallup Pakistan - Pakistan's Foremost Research Lab

https://gallup.com.pk/post/37337

Overall literacy rate improved by 1.8%, from 58.9% in 2017 to 60.7% in 2023; highest literacy rate recorded was among the 13-14 year olds living in urban areas (88.8%) – Literacy Rate – 7th Pakistan Population and Housing Census

Islamabad, September 5th, 2024

Gallup Pakistan, as part of its Big Data Analysis initiative, is looking at Literacy Rates for Pakistan. This data is part of a study conducted using the ‘7th Pakistan Population and Housing Census’.

The current edition looks at data from 7th Pakistan Population and Housing Census, which can be found HERE.

Today’s topic is “Literacy Rate in Pakistan” from tables 12 and 13a of the 7th Pakistan Population and Housing Census

Key Findings:

1.Literacy Rate for Pakistan: Overall literacy rate improved by 1.8%, from 58.9% in 2017 to 60.7% in 2023.

2.Literacy Rate by Province: From 2017 to 2023, the total literacy rate in Punjab, Sindh and ICT increased by 2.3%, 2.9% and 2.5% respectively, while it fell for KP by 2.9% and for Balochistan by 1.6%.

3.Literacy Rate by Region: Between 2017 to 2023, urban areas showed a modest increase of 0.9%, while rural areas saw a more substantial rise of 1.5% in their literacy rates.

4.Literary Rate by Age Group: Within age groups, the highest literacy rate recorded was among the 13-14 year olds living in urban areas (88.8%).

5.Gender and Regional Literacy Gaps narrow to 0.7% and 9.5% among Pakistan’s youngest age group (5-9 year olds).

Comment

- ‹ Previous

- 1

- …

- 12

- 13

- 14

- Next ›

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

IMF Questions Modi's GDP Data: Is India's Economy Half the Size of the Official Claim?

The Indian government reported faster-than-expected GDP growth of 8.2% for the September quarter. It came as a surprise to many economists who were expecting a slowdown based on the recent high-frequency indicators such as consumer goods sales and durable goods production, as well as two-wheeler sales. At the same time, The International Monetary Fund expressed doubts about the Indian government's GDP data. …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on November 30, 2025 at 11:30am

Retail Investor Growth Driving Pakistan's Bull Market

Pakistan's benchmark index KSE-100 has soared nearly 40% so far in 2025, becoming Asia's best performing market, thanks largely to phenomenal growth of retail investors. About 36,000 new trading accounts in the South Asian country were opened in the September quarter, compared to 23,600 new registrations just three months ago, according to Topline Securities, a brokerage house in Pakistan. Broad and deep participation in capital markets is essential for economic growth and wealth…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on November 24, 2025 at 2:05pm — 2 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network