PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

India Among Biggest Losers and Pakistan Among Biggest Gainers in World Happiness Rankings

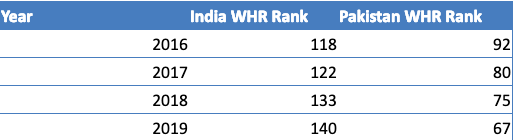

World Happiness Report 2019 says that India is among the world's biggest losers while Pakistan is among the biggest gainers on World Happiness Index. Under Prime Minister Narendra's Modi's leadership, India's ranking has worsened from 118 in 2016 to 140 in 2019. In the same period, Pakistan's ranking has improved from 92 in 2016 to 67 in 2019. World Happiness index is considered a better representation of people's well-being than other economic and social indicators individually.

World Happiness Trends in India and Pakistan. Source: United Nations |

Contrary to the Indian and western media hype about Modi-nomics, it was recently reported that unemployment rate in India has reached its highest in 45 years. Indian GDP growth figures have been challenged as too optimistic by top Indian and western economists. Modi's demonetization has turned out to be a major disaster for India's largely cash-based economy. Farmers are continuing to take their own lives by the thousands each year as the agrarian crisis continues to take its toll. India's community fabric has been fraying with sharp spike in social hostilities against minorities.

|

This year's United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network's annual World Happiness Report ranked 156 countries based on 6 indicators: income per capita, life expectancy, social support, freedom, generosity and corruption.

Countries in Scandinavia continue to to top the list while Sub-Saharan African nations remain at the bottom. Pakistan ranks 67 among 156 countries, tops South Asia region. China ranks 93, Bhutan 95, Nepal 100, Iran 117, Bangladesh 125, Iraq 126, India 140 and Afghanistan at 154.

Indian Prime Minister Modi has been accused by his critics of stoking tensions with Pakistan ahead of this year's general elections to divert attention from his government's poor performance. Some analysts believe that recent Indian airstrikes in Pakistan have helped bolster Modi's domestic support among his among his right-wing Hindu Nationalists base.

|

While Modi may have made domestic political gains, India's international perception as a "great power rising" has suffered a serious setback as a result of its recent military failures against Pakistan. Pakistan spends only a sixth of India's military budget and ranks 17th in the world, far below India ranking 4th by globalfirepower.com.

Related Links:

Pakistanis Happier Than Neighbors

Modi's GDP Growth Figures Challenged by Economists

Social Hostilities Spike in India Under Modi

Modi's Demonetization Disaster

Pakistan Rising or Failing: Reality vs Perception

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 23, 2019 at 4:17pm

-

The World Happiness Report combines quantitative data -- such as per capita GDP growth -- and qualitative data, such as social support, freedom to make life choices, and perceptions of corruption , to rank 156 countries.Pakistan's big edge in the happiness ranking over India may come as a surprise to some emerging market observers. India’s economy has been outperforming Pakistan’s in a number of metrics, like world competitiveness, GDP size and growth, and inflation rates - see table.Besides, India is a democracy that has yet to be interrupted by military coups.Pakistan’s, India’s Key Metrics (2018CountryIndiaPakistanGDP$2597.49 billion$304.95 billionGDP Growth yoy6.6%5.79%Unemployment6.1%5.9%Inflation Rate2.57%8.21%World Competitiveness Ranking58107Capital flows-$21.31 million-$1210.63 millionGovernment Debt to GDP68.7%72.5%Tradingeconomics.com 3/22/19So, what have Pakistanis done better than Indians in the pursuit of happiness?It’s hard to say. Most of the variables included in the calculations are qualitative, and therefore, prone to specification and measurement errors.Still , the gap between the rankings of the two countries is too big to be ignored.“It must be other metrics, like income inequality and poverty,” says Udayan Roy, Professor of Economics at LIU POST. “That’s matters more than per capita GDP when it comes to well-being of the masses.”Indeed, the rich are getting richer in India while the poor are getting poorer.Over the last four decades, India’s top 1% earners’ share of the country’s income rose from roughly 7% to 22%, as of 2014. Meanwhile, the income share of the bottom 50% earners declined from roughly 23% in the early 1980s to 15% in 2014.That’s according to 2018 World Inequality Report, which compiles data from the 1950s to 2014.Meanwhile, India’s income inequality is much higher than that of both Pakistan, and Bangladesh, as measured by the Gini coefficient of income inequality.That’s according to Standardized World Income Inequality data.Meanwhile, poverty rates are higher in India than they are in Pakistan and Bangladesh, according to World Bank.Then there’s “vulnerable employment”— employment in unpaid family activities—which is much higher in India than in Pakistan and Bangladesh.Wait, there’s more. There’s economic freedom.Published by the Heritage Foundation, the Economic Freedom report measures such things as trade freedom, business freedom, investment freedom, and the degree of property rights protection in 186 countries.Though the two countries have ranked closely in the last couple of years, Pakistan’s ranking has consistently beaten India's over longer periods.In fact, a closer look at the ranking components of the two countries reveals that Pakistan has fared better than India in the area of government spending, which matter a great deal when it comes to providing on welfare programs.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 24, 2019 at 6:57pm

-

#India's crony capitalist edifice is creaking. A bank-dominated financial system hasn’t just saddled India with more than $200 billion in bad loans; it’s also been the bane of governance. #Modi #BJP #inequality #economy https://theprint.in/opinion/indias-crony-capitalist-edifice-is-crea... via @ThePrintIndia

For at least six decades, scholars and policy makers have been aware of the strain placed by India’s feudal system of corporate governance on capital formation, job creation and growth. Yet the last major reform was in 1969, which ironically was also when India was nationalizing banks and lurching toward a more virulent socialism. Subsequently, globalization caught up with India, the economy opened up and attracted hundreds of billion dollars in foreign capital, but the foundations of corporate structure stayed weak. It’s only now, when the edifice is showing cracks, that it’s becoming clear a fresh coat of paint alone won’t suffice.

Back in the 1960s, “managing agencies” dominated India’s industrial landscape. The 70 companies in the Tata Group were run by nine agencies, while 49 firms in the Birla Group were managed by 13. Such was the sway of the “boxwallahs,” as the agents were pejoratively referred to, that State Bank of India wouldn’t lend to an operating company without its managing agency’s guarantee. Nevermind that a majority of these proxy controllers didn’t even have 1 million rupees in capital of their own. They were vehicles for business families to extract commissions and control empires in the garb of providing managerial expertise.

Andrew Yule, Martin Burn, W.H. Brady and MacNeill & Barry. As the names suggest, the managing agencies started out as part of the British colonial project, but about a hundred years ago ownership started to pass into Indian hands. The world wars and India’s 1947 independence hastened the switch. India eventually outlawed managing agencies in 1969, but entrenched families lost no time in gaming the corporate boards that were now in charge.

Explicit recognition of some shareholders as “promoters” has perpetuated their exorbitant privilege, and infected even firms of a newer vintage. The co-founders of Mindtree Ltd., a mid-bracket software services company, didn’t show any urgency when a large investor warned them of his intention to cash out. Now that the investor has sold to engineering firm Larsen & Toubro Ltd., the insiders are shocked, shocked that L&T is out to “decimate” Mindtree with a $1.6 billion hostile takeover.

Mindtree founders are first-generation entrepreneurs. You can imagine the sense of entitlement that may be felt by the more pedigreed families that control 60 percent of the assets of publicly traded companies. In the 1970s, William Meckling and Michael Jensen studied the friction between managers and a diffuse U.S.-style shareholder base, whereas in Asia, the main issue is concentrated ownership and expropriation by insiders whose political connections get them bank loans.

A bank-dominated financial system hasn’t just saddled India with more than $200 billion in bad loans; it’s also been the bane of governance. Recently, Indian banks did an out-of-court settlement in Sterling Biotech Ltd., taking a 65 percent haircut while handing back control to the same promoters who’ve left India and are facing charges of money-laundering.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 8, 2019 at 10:10am

-

"Despite official figures #India’s economy slowed sharply due to #Modi's mis-steps while promised #jobs and #investments have not materialized...India has gone backwards under him. He is lying about the #GDP numbers....#Indian MBAs are working as waiters" https://www.ft.com/content/14baecba-56c5-11e9-91f9-b6515a54c5b1

Mr Modi swept to power in New Delhi in 2014, pledging to bring acche din, or good times, for India, with accelerated economic growth and millions of new jobs. But his record of delivery on these promises is highly contentious.

The prime minister insists India’s economy has grown faster under his leadership than ever before, with an average annual GDP growth of 7.3 per cent, compared with an annual average of 6.7 per cent under the previous Congress-led government. But many economists have questioned the credibility of official data, amid perceptions of unprecedented political interference. Even by New Delhi’s own numbers, India’s GDP growth slowed to 6.6 per cent in the three months ending December 31, its slowest pace in five quarters.

New Delhi has also suppressed a major report which apparently indicated rising joblessness among youth. In a Pew Research Center survey of 2,521 Indians last summer, 76 per cent cited lack of employment opportunities as a major concern. “The gap between the hype and the promises was clearly wide and clearly visible,” Mr Varshney says.

Farmers have been squeezed hard as part of the effort to curb once rampant inflation, their anger displayed in a series of large-scale protests. “We are very unhappy”, says Lakshman Ram, a 61-year-old farmer at the Jodhpur spice market, where he was selling a mound of fragrant cumin seeds to traders. “He has killed us farmers. He has finished us. I’m just waiting for Congress — they think about us.”

---------------

The Zomato and Swiggy delivery boys, however, brim with enthusiasm for Mr Modi, especially his recent authorisation of a missile strike on an alleged terrorist training camp in neighbouring Pakistan. Their excitement is mirrored by Akshay Bhati, 25, whose father supplies milk to the shop.

“The power of the nation has gone up,” the younger Mr Bhati says. “Before, any enemy country would come and attack India and just get away with it — India would not do anything. Now, we will enter your house and kill you.”

The divergent views among the evening crowd at Pokar’s reflects the deep faultlines among India’s 900m eligible voters, as they gear up for what has become an unusually personality-driven general election contest. The voting will serve as a national assessment of how well the charismatic populist Mr Modi has lived up to the high expectations he raised of a “New India”, when he took power in 2014 after 10 years of disappointing rule by the Congress party.

----

The premier’s Bharatiya Janata party, with its deep pockets and sophisticated political machinery, is urging India’s voters to give Mr Modi another five years in power to continue his efforts to remake India.

Fragmented opposition parties — including the BJP’s arch-rival Congress, led by Rahul Gandhi, and a diverse array of smaller regional parties — are trying to counter by accusing Mr Modi of failing to live up to expectations, and inflicting unnecessary misery on the population, while simultaneously taking potshots at one another. Results will be known only on May 23, as voting is spread over six weeks.

“It is undoubtedly a referendum on Mr Modi,” says Ashutosh Varshney, director of the Center for Contemporary South Asia at Brown University, of the contest. “It’s a very presidential style election.”

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 8, 2019 at 10:13am

-

Under the shadow of Jodhpur’s imposing Mehrangarh Fort, the Pokar Sweet Home is famous for its traditional Indian snacks: thick creamy lassis, batter-fried stuffed chilli peppers and chickpea flour dumplings. But these days, the food shop founded 80 years ago has a new stream of thoroughly modern visitors: young men — clad in the bright red and orange T-shirts of rival foreign-backed food delivery services Zomato and Swiggy — collecting orders placed online by customers across the city. Om Prakash Bhati, the 51-year-old son of Pokar’s late founder, says the recent launch of Zomato, Swiggy and Uber Eats in Jodhpur has boosted his sales dramatically, after a turbulent period when his business was hit by a draconian 2016 cash ban and a complicated overhaul of India’s tax system. Raghuvir Singh Meena from Rajasthan guards his chickpea crop against local cows. He, like many farmers, has been squeezed hard by rampant inflation © AFP “People who would never come here because of parking issues, they just order on line,” says Mr Bhati, sitting under a tree and constantly checking the large tablet where the orders from Zomato and Swiggy ping in. But if united by food, Pokar’s owner and the young couriers who deliver his delicacies differ sharply when it comes to their assessment of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, now seeking a second term in a general election contest whose weeks-long voting process starts on Thursday. Mr Bhati, who voted for Mr Modi in 2014, is bitterly disappointed with what has happened over the past five years. He believes that despite official figures India’s economy slowed sharply due to the premier’s mis-steps while promised jobs and investments have not materialised. “Modi raised expectation that he was going to transform the country,” he says. “But India has gone backwards under him. He is lying about the GDP numbers. People who have done MBAs are working as waiters.” BJP’s arch-rival Congress, led by Rahul Gandhi, centre, has accused Mr Modi of failing to live up to expectations © Getty The Zomato and Swiggy delivery boys, however, brim with enthusiasm for Mr Modi, especially his recent authorisation of a missile strike on an alleged terrorist training camp in neighbouring Pakistan. Their excitement is mirrored by Akshay Bhati, 25, whose father supplies milk to the shop. “The power of the nation has gone up,” the younger Mr Bhati says. “Before, any enemy country would come and attack India and just get away with it — India would not do anything. Now, we will enter your house and kill you.” The divergent views among the evening crowd at Pokar’s reflects the deep faultlines among India’s 900m eligible voters, as they gear up for what has become an unusually personality-driven general election contest. The voting will serve as a national assessment of how well the charismatic populist Mr Modi has lived up to the high expectations he raised of a “New India”, when he took power in 2014 after 10 years of disappointing rule by the Congress party. Known for his decisiveness, risk-taking and his highly-personalised operating style, Mr Modi has dominated India’s political landscape like no other leader since Indira Gandhi, who is still remembered for her own strong, authoritarian streak. He has mesmerised the public with a vision of an India which enjoys a modern, developed economy, an efficient honest government and global stature, while remaining rooted in the traditional values and social mores of its Hindu majority. The premier’s Bharatiya Janata party, with its deep pockets and sophisticated political machinery, is urging India’s voters to give Mr Modi another five years in power to continue his efforts to remake India. Fragmented opposition parties — including the BJP’s arch-rival Congress, led by Rahul Gandhi, and a diverse array of smaller regional parties — are trying to counter by accusing Mr Modi of failing to live up to expectations, and inflicting unnecessary misery on the population, while simultaneously taking potshots at one another. Results will be known only on May 23, as voting is spread over six weeks. “It is undoubtedly a referendum on Mr Modi,” says Ashutosh Varshney, director of the Center for Contemporary South Asia at Brown University, of the contest. “It’s a very presidential style election.” Demonetisation chaos: Customers exchange one thousand rupee banknotes at a Syndicate Bank branch in Dadri, Uttar Pradesh © Bloomberg Mr Modi swept to power in New Delhi in 2014, pledging to bring acche din, or good times, for India, with accelerated economic growth and millions of new jobs. But his record of delivery on these promises is highly contentious. The prime minister insists India’s economy has grown faster under his leadership than ever before, with an average annual GDP growth of 7.3 per cent, compared with an annual average of 6.7 per cent under the previous Congress-led government. But many economists have questioned the credibility of official data, amid perceptions of unprecedented political interference. Even by New Delhi’s own numbers, India’s GDP growth slowed to 6.6 per cent in the three months ending December 31, its slowest pace in five quarters. New Delhi has also suppressed a major report which apparently indicated rising joblessness among youth. In a Pew Research Center survey of 2,521 Indians last summer, 76 per cent cited lack of employment opportunities as a major concern. “The gap between the hype and the promises was clearly wide and clearly visible,” Mr Varshney says. Farmers have been squeezed hard as part of the effort to curb once rampant inflation, their anger displayed in a series of large-scale protests. “We are very unhappy”, says Lakshman Ram, a 61-year-old farmer at the Jodhpur spice market, where he was selling a mound of fragrant cumin seeds to traders. “He has killed us farmers. He has finished us. I’m just waiting for Congress — they think about us.” Indeed, when rural anger helped Congress unexpectedly win three state elections in former BJP strongholds in December, it suggested that Mr Modi was politically vulnerable and the national polls could be more competitive than expected. But since the February 14 terrorist attack that killed 40 Indian paramilitaries in the disputed Kashmir region, Mr Modi has deftly turned public attention away from his controversial economic record towards national security. His approval of an air strike on an alleged Pakistani terror training centre in Balakot on February 26 elated Indians long frustrated with New Delhi’s traditional restraint after provocations such as the 2001 attack on parliament and the 2008 attacks in Mumbai. New Delhi’s claim that its missiles killed 300 Pakistani terrorists — which is doubted by western governments — has found a receptive domestic audience, and even been celebrated in a catchy Bollywood-style music video widely circulating on social media. Om Prakash Bhati, a food shop owner, says the recent launch of Zomato, Swiggy and Uber Eats in Jodhpur has boosted sales dramatically after a turbulent period Overall, the missile strike — whatever its real impact on the ground — has undoubtedly boosted Mr Modi’s popularity, reinforcing his image as a bold and decisive leader. He sought to consolidate this with a national broadcast on March 27, when he announced that New Delhi had just successfully tested an anti-satellite missile, joining what he called the space “super-league”. The showdown with Pakistan, and subsequent sharp focus on national security, has had the added bonus of galvanising BJP workers and volunteers. “National security essentially gives a leader an opportunity to show determination and resolve,” says Mr Varshney. “Now we also have an organisation [the BJP] whose morale has been boosted by Balakot, and which is working even more enthusiastically for a leader who had seemed to be in a fair amount of trouble.” Even without the Balakot boost, analysts say Mr Modi already had a good shot at a second term, although his support has been eroding somewhat. Pew’s survey last spring found that 55 per cent of Indians were generally satisfied with the country’s direction. Though down sharply from the soaring 70 per cent a year earlier, it still reflected an upbeat attitude. Mr Modi also remains personally popular, with his image of honesty, integrity and hard work still intact. Talks of a united opposition front between Congress and regional parties to fight Mr Modi also petered out, with Mr Gandhi’s party instead opting to go it alone, ensuring the anti-BJP vote will be divided. That is a major boon to the ruling party, given India’s first-past-the-post parliamentary system. “It might mean the difference between defeat and victory,” says Gilles Verniers, a political-science professor at Ashoka University. “Historically, large national parties can only be defeated by a united opposition. Instead, Congress is going to play spoiler in states where the contest is really about the BJP versus strong regional parties. It’s going to benefit the BJP enormously.” A few blocks from Pokar’s stands a half empty shopping mall with a McDonald’s, where the elegantly dressed Renu Khichi, a police officer’s wife, is dining with her two teenagers. She admits she was dissatisfied with the economy’s trajectory over the past five years — especially Mr Modi’s signature cash ban. “The poor suffered, the middle-class suffered and the rich didn’t have to worry,” she says. Yet she feels “proud” of the missile strike in Pakistan, saying “if somebody attacks you, you have to respond.” She is forgiving of Mr Modi’s mistakes, confident in his good intentions, and willing to give him a second chance. Renu Khichi is dissatisfied with the economy’s trajectory over the past five years “For 70 years, Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi didn’t do anything so even if he didn’t deliver, neither did they,” she says. “I feel he should be given another five years, and I’m hopeful he will do something.” Across the city on the top floor of the Ashapurna Mall — which claims to be “where dreams meet reality” but where the anchor tenants are two middle-class clothing brands — Lokesh Anupani, a medical doctor, and his wife, Madhvi, a dentist, watch their three-year-old daughter jumping around a children’s play area. Dr Anupani says he supports the prime minister, who he sees as hard-working and honest. But he says he also believes that the opposition Congress needs to remove Mr Gandhi — the son, grandson and great-grandson of former Indian prime ministers — if it is ever to be a serious contender for power. “He is childish,” the young doctor says of Mr Gandhi. “He is not mature enough to handle this country. He is only in politics due to his surname, but he has no ability. I am not opposed to Congress, but if they want to be a good opposition party, or be in government they should promote someone else. Otherwise, Narendra Modi will keep winning.” Lokesh Anupani, a medical doctor, and his family. He sees the prime minister as hard-working and honest Gokul Choudhury is a 37-year-old driver who has a college degree in arts, and feels unhappy with his lot as a driver. When he voted for Mr Modi in 2014, he hoped the prime minister’s promised creation of new jobs might help him land a different kind of work. That has not happened. “It’s a very bad situation”, he says. “There are no jobs.” Yet even if his own personal dreams have not been realised, Mr Choudhury says he will cast a vote for Mr Modi one more time in the upcoming polls — to give the prime minister more time to bring the development he promised. “There were so many problems left by the last government,” he says. “But I think things will get better.” But he believes many voters will look past their own difficulties to support a leader now helping India to stand tall on the world stage. “Modi has created this feeling of nationalism, and patriotism”, he says. “It is this feeling, don’t think about yourself and your own interests only. Think about the nation first.” Additional reporting by Jyotsna Singh Undertones of bigotry lie beneath campaign message On the surface, India’s upcoming general election campaign is focused on issues familiar to any lively democracy: the economy and national security challenges. But beneath the veneer lie strong undertones of religious bigotry. Mr Modi himself is careful in his public comments, insisting that he works neither for the country’s Hindu majority, nor its Muslim minority. But other senior BJP leaders are stoking Hindus’ deep-seated mistrust of Muslims, while depicting the rival Congress party as “anti-Hindu” and “pro-Muslim”. Yogi Adityanath, the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, and one of the BJP’s star campaigners in the current contest, has described the Congress as “infected with the virus” of the Muslim League — a reference to the political organisation that pushed for the division of the Indian subcontinent to create a separate Muslim-majority Pakistan at the end of British colonial rule. In Jodhpur’s Clock Tower market, Kishore Changlani, the 35-year-old, third-generation owner of Maharani Spices, is a dedicated BJP volunteer. His grandfather arrived in Jodhpur in 1947 as a Hindu refugee from Sindh province, which became part of Pakistan. Mr Changlani still harbours resentment over the loss of his family’s wealth in the upheaval, for which he blames both Congress, and Muslims more generally. He supports Mr Modi in part because he believes he is a strong leader. Repeating a long-standing rightwing canard that Muslims' high birthrate will tip India's demographic balance against Hindus, the spice trader says: "Mr Modi can control the population and ensure an equal law for everyone. Otherwise India will also become Pakistan — if Muslims keep having so many babies.”

-

Comment by Uzair Ansari on April 9, 2019 at 5:10am

-

It comes off as a true surprise when we witness Pakistan performing better than its neighbouring counterpart on the "World Happiness" forum. Quite imperatively, this better ranking could only have been achieved via much higher scores in nearly all social sectors encompassing the general population. Taking into acccount Pakistan's performance among the South Asian countries, it certainly runs better than the rest of the members, topping the happiness ratio. It becomes quite evident that despite being a much bigger economy and a global market niche, the Indian society just couldn't translate its better economic conditions into a happier, contended populace. One might argue that the Indian peninsula is vast in its land area as well as its population types and density distribution that have all combined to contribute to its lower-than-expected happiness figures. True enough, but then this assumption points to its another negative aspect --- the inequal distribution of resources and opportunities among its living classes of citizens. All in all, even a higher GDP growth, dollar reserves, military personnel and arsenal and a much larger world market, it is the global gauge now that is speaking lowly of its happiness extent. They need to buck up if they intend to lie any closer to us.

I have gathered some information from the internet

reference https://www.parhlo.com/

dawn news

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 13, 2020 at 6:34pm

-

#India's #Modi is turning to deregulation amid an #economic crisis. So far, the overhaul has led to more confusion. The poor have been hit hardest by #COVID19, with migrants returning from cities & unable to support families in rural areas. #BJP https://www.wsj.com/articles/india-turns-to-economic-overhaul-as-gr... via @WSJ

measures—the BJP passed a flurry of politically difficult changes.

In a single swoop, it dismantled a longstanding regulatory system that forced farmers to sell most of their crops through government-approved wholesale markets dominated by traders and middlemen instead of directly to consumers or food processors.

Then the BJP passed a series of new labor measures that increased the number of companies that can fire workers without government permission, raised the barriers for workers to unionize, relaxed rules preventing women from working night shifts and restricted unions’ ability to organize strikes. At the same time, it expanded the country’s social security program to include many contract workers.

Jitendra Singh, a minister in the BJP government, said the changes would ultimately improve farmers’ economic prospects, especially in far-flung rural areas, by giving them more options for selling their crops. The BJP has also said it doesn’t intend to phase out government wholesale markets or minimum price supports.

The agricultural industry overhaul went into effect immediately, while most of the labor-market changes will be implemented before the end of the year.

The measures add to a mixed record of economic changes by Mr. Modi and the BJP. The prime minister’s controversial 2016 move to instantly remove almost 90% of the country’s currency in circulation hobbled the economy for years with little benefit to show for it, economists say. Overhauls of the country’s bankruptcy code and the country’s tax system have been broadly applauded, despite complaints about how they have been implemented.

The latest changes have sparked an uproar, including from opposition parties that once promoted the very same policies and even from farmers who are supposed to be the main beneficiaries.

----------

Economists say the changes could ultimately be a boon for the Indian economy, which depends heavily on agriculture. Farming accounts for about 17% of total income in the country, and provides employment for close to two-thirds of India’s working-age population.

The daunting challenge may be implementing them during a double-barreled economic and health crisis—even though the desperation of the country’s economic state is what finally cleared a political path for an initiative both the BJP and its main opposition have at times supported.

“In a word, all reforms are good in theory,” said Vivek Dehejia, an expert on the Indian economy at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. “In practice, I worry it may be too little too late, and I’m not confident that market incentives work well during a time of a public safety emergency.”

If the changes can be maintained long enough for legions of traders and middlemen entrenched by the government-created monopoly wholesale markets to be replaced by competitive markets, then farmers should ultimately benefit by capturing at least some of the profits that have traditionally gone to those buying and reselling their crops, said Shubho Roy, an economist at the University of Chicago who has studied the wholesale market system.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 30, 2022 at 7:23pm

-

AT 9.4 out of a maximum possible score of 10, India’s Social Hostilities Index (SHI) in 2020 was worse than neighbouring Pakistan and Afghanistan, and a further increase in its own index value for 2019, the Pew data showed. A higher score is worse. The report covered 198 countries.

https://www.livemint.com/news/india/communal-rift-highest-in-india-...

-------------

Indian American Muslim Council

@IAMCouncil

A latest

@pewresearch

report notes that India’s Social Hostilities Index (SHI) in 2020 was worse than Afghanistan, Syria & Mali.

https://twitter.com/IAMCouncil/status/1598143658796412928?s=20&...

--------

In India, the Ministry of Home Affairs announced in April 2020 that more than 900 members of the Islamic group Tablighi Jamaat and other foreign nationals (most of whom were Muslim) had been placed “in quarantine” after participating in a conference in New Delhi allegedly linked to the spread of early cases of coronavirus. (Many of those detained were released or granted bail by July 2020.)

Pandemic-related killings of religious minorities were reported in three countries in 2020, according to the sources analyzed in the study. In India, two Christians died after they were beaten in police custody for violating COVID-19 curfews in the state of Tamil Nadu.

In India, there were multiple reports of Muslims being attacked after being accused of spreading the coronavirus. In Argentina and Italy, properties were vandalized with antisemitic posters and graffiti that linked Jews to COVID-19. In Italy, for example, authorities found graffiti of a Star of David with the words “equal to virus.” And in the U.S., a Mississippi church burned down in an arson attack about a month after its pastor sued the city over public health restrictions on large gatherings. Investigators found graffiti in the church parking lot that said, “Bet you stay home now you hypokrits.”

https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2022/11/29/how-covid-19-restri...

Comment

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

US-India Ties: Strategic or Transactional?

During the last Trump Administration in 2019, India's friends in Washington argued for a US policy of "strategic altruism" with India. The new Trump administration seems to be rejecting such talk. Prior to his recent meeting with Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the White House, President Donald Trump described India as the "worst abuser of tariffs" and announced "reciprocal tariffs" on Indian…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on February 19, 2025 at 10:00am — 1 Comment

Pakistan Navy Plans Modernization, Indigenization

Admiral Naveed Ashraf, Pakistan Navy Chief, spoke of his vision for "indigenization and modernization" of his branch of the Pakistani military on the eve of multinational AMAN 2025 naval exercises. Biennial AMAN Exercise and Dialogue this year attracted 60 nations from Australia to Zimbabwe (A to Z). China, the United States, Turkey and Japan were among the countries which…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on February 13, 2025 at 9:30am — 2 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network