PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Demography is Destiny

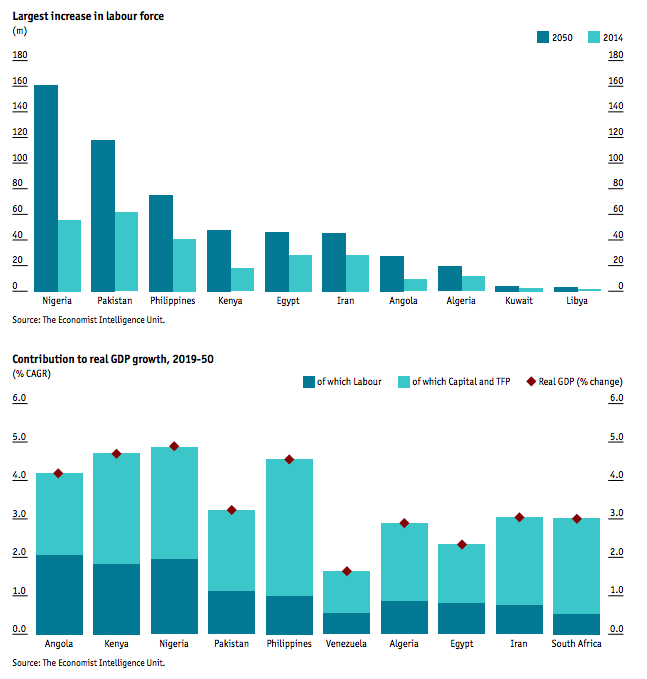

Pakistan has the world’s sixth largest population, seventh largest diaspora and the ninth largest labor force. With rapidly declining fertility and aging populations in the industrialized world, Pakistan's growing talent pool is likely to play a much bigger role to satisfy global demand for workers in the 21st century and contribute to the well-being of Pakistan as well as other parts of the world.

|

| Source: Economic Intelligence Unit of The Economist Magazine |

With half the population below 20 years and 60 per cent below 30 years, Pakistan is well-positioned to reap what is often described as "demographic dividend", with its workforce growing at a faster rate than total population. This trend is estimated to accelerate over several decades. Contrary to the oft-repeated talk of doom and gloom, average Pakistanis are now taking education more seriously than ever. Youth literacy is about 70% and growing, and young people are spending more time in schools and colleges to graduate at higher rates than their Indian counterparts in 15+ age group, according to a report on educational achievement by Harvard University researchers Robert Barro and Jong-Wha Lee. Vocational training is also getting increased focus since 2006 under National Vocational Training Commission (NAVTEC) with help from Germany, Japan, South Korea and the Netherlands.

Pakistan's work force is over 60 million strong, according to the Federal Bureau of Statistics. With increasing female participation, the country's labor pool is rising at a rate of 3.5% a year, according to International Labor Organization.

With rising urban middle class, there is substantial and growing demand in Pakistan from students, parents and employers for private quality higher education along with a willingness and capacity to pay relatively high tuition and fees, according to the findings of Austrade, an Australian govt agency promoting trade. Private institutions are seeking affiliations with universities abroad to ensure they offer information and training that is of international standards. Trans-national education (TNE) is a growing market in Pakistan and recent data shows evidence of over 40 such programs running successfully in affiliation with British universities at undergraduate and graduate level, according to The British Council. Overall, the UK takes about 65 per cent of the TNE market in Pakistan.

Trans-national education (TNE) is a growing market in Pakistan and recent data shows evidence of over 40 such programs running successfully in affiliation with British universities at undergraduate and graduate level, according to The British Council. Overall, the UK takes about 65 per cent of the TNE market in Pakistan.

It is extremely important for Pakistan's public policy makers and the nation's private sector to fully appreciate the expected demographic dividend as a great opportunity. The best way for them to demonstrate it is to push a pro-youth agenda of education, skills development, health and fitness to take full advantage of this tremendous opportunity. Failure to do so would be a missed opportunity that could be extremely costly for Pakistan and the rest of the world.

|

| Working Age Population Growth in Pakistan. Source: UNFPA |

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Pakistanis Study Abroad

Pakistan's Youth Bulge

Pakistani Diaspora World's 7th Largest

Pakistani Graduation Rate Higher Than India's

India and Pakistan Contrasted in 2011

Educational Attainment Dataset By Robert Barro and Jong-Wha Lee

Quality of Higher Education in India and Pakistan

Developing Pakistan's Intellectual Capital

Intellectual Wealth of Nations

Pakistan's Story After 64 Years of Independence

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 10, 2019 at 9:52am

-

The 2030 Skills Scorecard

Bridging business, education, and the future of workSouth Asia has experienced some of the fastest economic growth rates globally. If strong investments in skills development are made, the region is poised to maintain growth in the coming decades. Today, South Asia is home to the largest number of young people of any global region, with almost half of its population of 1.9 billion below the age of 24. Youth unemployment remains high (at 9.8% in 2018) because of changing labor market demands and over — or under — qualification of job candidates. In most South Asian countries, the projected proportion of children and youth completing secondary education and learning basic secondary skills is expected to more than double by 2030. Still, on current trends, fewer than half of the region’s projected 400 million primary and secondary school-age children in 2030 are estimated to be on track to complete secondary education and attain basic workforce skills.

----------------------------------------------More than half of South Asian youth are not on track to have the education and skills necessary for employment in 2030

With almost half of its population of 1.8 billion below the age of 24, led by India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, South Asia will have the largest youth labour force in the world until 2040.This offers the region the potential to drive vibrant and productive economies. If strong investments in skills development are made, the region is poised to maintain strong economic growth as well as an expansion of opportunities in the education and skills sectors in the coming decades.* These estimates were generated based on a 2019 update of the Education Commission’s original 2016 projections model for the Learning Generation report. Most recent national learning assessment data used for each country as follows: BCSE 2015 for Bhutan, GCE O Levels 2016 for Sri Lanka, LASI 2015 for Bangladesh, NAT 2016 for Pakistan, NCERT 2017 for India, Nepali country assessment 2017 for Nepal, O Level Exam 2016 for Maldives. Afghanistan is not included due to lack of recent learning assessment data at the secondary level.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 10, 2019 at 10:00am

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 11, 2021 at 10:18am

-

Falling Populations May Keep Poor Countries From Getting Rich - Bloomberg

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-07-26/falling-popul...

New population estimates suggest the window for many big developing nations may be closing faster than they realized.

The United Nations currently predicts that by 2027, India will overtake China as the world’s most populous country. Estimates suggest India and Nigeria will together add 470 million people in the next three decades — almost a quarter of the world’s population increase to 2050. According to a new study from the University of Washington, however, several developing nations may find their so-called demographic dividend much less of a boon than anticipated.

Published in the Lancet, the UW study has improved on the UN’s model by modelling fertility differently and making its decline more sensitive to the availability of contraception and the spread of education. In many parts of India, for instance, the total fertility rate — the expected average number of children born to each woman — is already well below the replacement rate of 2.1 and dropping faster than expected. The study, which also tries to account for the feedback loops between education, mortality and migration, concludes that populations around the world are going to start shrinking sooner and faster than projected.

South Asia, for example, would have 600 million fewer people in 2100 than previously predicted thanks to lower-than-expected levels of fertility. Instead of growing throughout, India’s population would peak in 2050 and then decline to 70% of that number by the end of the century. By that point, China’s population would be about half its current size. On the other hand, sub-Saharan Africa would continue to grow, with Nigeria entering the 22nd century as the world’s second-largest country, behind India and just ahead of China and Pakistan.

For policymakers in India and several other developing nations, this isn’t good news. As the authors of the UW study point out, a shrinking global population has “positive implications for the environment, climate change, and food production.” But it also means time is running out — indeed, may already have run out — on those nations’ development clocks.

China has been truly fortunate in its demographics; it peaked at the right time. Working-age Chinese people, both in total numbers and as a share of the population, crested just when world trade was most open. This made the possibilities for manufacturing-led growth easier to seize than they had been for centuries.

Those countries that come next — India and Pakistan in particular — will confront a more closed world. And, worse, they now know that it is people currently in the workforce, or children in school, who over their lifetimes will have to lift the country to prosperity. For countries whose populations will begin to decline in the 2040s, this generation of workers and the next is all there is: They must, like their Chinese counterparts in the last two decades, push their countries from farm to factory and beyond.

Right now, India’s boosters tout the fact that its working-age population swells by a million people a month, propelling economic growth. If that demographic push runs out sooner than expected, growth will depend on individual productivity, not sheer numbers. That means education and healthcare and similar “soft” infrastructure no longer look like rich-country luxuries. Unless they are put into place within the next decade, indeed within the next few years, countries such as India, Indonesia and Brazil may never become rich.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 11, 2021 at 10:19am

-

Falling Populations May Keep Poor Countries From Getting Rich - Bloomberg

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-07-26/falling-popul...

New population estimates suggest the window for many big developing nations may be closing faster than they realized.

The United Nations currently predicts that by 2027, India will overtake China as the world’s most populous country. Estimates suggest India and Nigeria will together add 470 million people in the next three decades — almost a quarter of the world’s population increase to 2050. According to a new study from the University of Washington, however, several developing nations may find their so-called demographic dividend much less of a boon than anticipated.

Published in the Lancet, the UW study has improved on the UN’s model by modelling fertility differently and making its decline more sensitive to the availability of contraception and the spread of education. In many parts of India, for instance, the total fertility rate — the expected average number of children born to each woman — is already well below the replacement rate of 2.1 and dropping faster than expected. The study, which also tries to account for the feedback loops between education, mortality and migration, concludes that populations around the world are going to start shrinking sooner and faster than projected.

South Asia, for example, would have 600 million fewer people in 2100 than previously predicted thanks to lower-than-expected levels of fertility. Instead of growing throughout, India’s population would peak in 2050 and then decline to 70% of that number by the end of the century. By that point, China’s population would be about half its current size. On the other hand, sub-Saharan Africa would continue to grow, with Nigeria entering the 22nd century as the world’s second-largest country, behind India and just ahead of China and Pakistan.

For policymakers in India and several other developing nations, this isn’t good news. As the authors of the UW study point out, a shrinking global population has “positive implications for the environment, climate change, and food production.” But it also means time is running out — indeed, may already have run out — on those nations’ development clocks.

China has been truly fortunate in its demographics; it peaked at the right time. Working-age Chinese people, both in total numbers and as a share of the population, crested just when world trade was most open. This made the possibilities for manufacturing-led growth easier to seize than they had been for centuries.

Those countries that come next — India and Pakistan in particular — will confront a more closed world. And, worse, they now know that it is people currently in the workforce, or children in school, who over their lifetimes will have to lift the country to prosperity. For countries whose populations will begin to decline in the 2040s, this generation of workers and the next is all there is: They must, like their Chinese counterparts in the last two decades, push their countries from farm to factory and beyond.

---------------

Even the most fortunate countries will need to be careful. By 2050, as expected, China will be the world’s largest economy. But the study authors predict that, as the Chinese population declines, immigration should in theory continue to bolster America’s workforce. The U.S. could again become the world’s largest economy in 2098 — if the country lives up to its ideals and continues to welcome the world’s migrants. There’s no better way to ensure America becomes great again.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 11, 2021 at 10:50am

-

CAPTURING THE

DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND

IN PAKISTAN

ZEBA A. SATHAR

RABBI ROYAN

JOHN BONGAARTS

EDITORS

WITH A FOREWORD BY DAVID E. BLOOM

https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2013_CapturingDemoDivPak.pdfA recent study by the IMF (Kock and Sun 2011), which examined the rapid increase in remittances over the past decade (from just over US$1 billion

in 2000–01 to an expected US$13 billion in 2011–12), finds for the period 1997–2008

that both the numbers of Pakistanis going overseas for work and the skill levels of these immigrants have increased. Since a large proportion of migrants are relatively young, one must ask whether better-educated and highly skilled young people are leaving the country in disproportionately high numbers.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 11, 2021 at 10:53am

-

These are the countries most affected by the decline in working age populations

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/01/declining-working-age-popula...

- Within the OECD, countries such as Korea, Japan, Germany and Italy have a declining working age population.

- The OECD calculated that Japan is the country most heavily affected, as its working population is set to be just 60% of its original size by 2050.

Within the OECD, Korea, Japan, Germany and Italy are among the countries most heavily affected by a decline of their working age populations. Taking each country’s population between the ages of 20 and 64 in the year 2000 as a base, the OECD calculated that by 2050, that population would only be around 80 percent of its original size in Korea and Italy. In Japan, the country most heavily affected, that number would be just over 60 percent.

For the OECD in total, the size of the working age population is actually expected to increase and be at 111 percent of the 2000 figure in 2050. The growth is driven by countries with strong birth rates and large populations, like Australia, Turkey and the United States.

While Japan’s working age population has been in decline since the 1990s, Korea’s working age population was expected to start its decline in 2019. The country's statistics bureau just confirmed that the entire population of South Korea in fact declined by 0.04 percent in 2020.

For countries experiencing a decline of working age population, problems like underfunded social systems, tight labor markets and an overstretched medical and care sector are common

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 18, 2021 at 9:29pm

-

#America's population is aging. We need learn to live with low fertility. #US is going to be living for a long time with slow population growth & low #GDP growth. And we need to start thinking about #economic policy with that reality in mind. #demographics https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/17/opinion/low-population-growth-ec...

Last week the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported much higher inflation than almost anyone predicted, and inflationistas — people who always predict runaway price rises, and have always been wrong — seized on the news as proof that this time the wolf is real.

Financial markets, however, took it in stride. Stocks fell on the report, but they soon made up most of the losses.

Bond yields rose only slightly on the news, then ended the week right where they started — namely, extremely low.

Why so little reaction to the inflation news? Part of the answer, presumably, was that once investors had time to digest the details they realized that there was little sign of a rise in underlying inflation; this was a blip reflecting what were probably one-time rises in the prices of used cars and hotel rooms.

Beyond that, however, is what I think is the realization that while we’re achieving dramatic, almost miraculous success in defeating Covid-19, once the pandemic subsides we’re likely to be in an environment of sustained low interest rates as a result of weak investment demand. And the biggest reason for that low-rate environment is plunging fertility, which implies slow or even negative growth in the number of Americans in their prime working years.

This isn’t a new issue. Last month’s census report showing the lowest U.S. population growth since the 1930s only confirmed what everyone studying the subject already knew. And America is relatively late to this party. Japan’s working-age population has been declining since the mid-1990s. The euro area has been on the downslope since 2009. Even China is starting to look like Japan, a legacy of its one-child policy.

Is stagnant or declining population a big economic problem? It doesn’t have to be. In fact, in a world of limited resources and major environmental problems there’s something to be said for a reduction in population pressure. But we need to think about policy differently in a flat-population economy than we did in the days when maturing baby boomers were rapidly swelling the potential work force.

OK, let me admit that there is one real issue: An aging population means fewer active workers per retiree, which raises some fiscal issues. But this problem is often exaggerated. Remember all the panic about how Social Security couldn’t survive the burden of retiring boomers? Well, many boomers have already retired; by 2025 most of the growth in the number of beneficiaries per worker caused by retiring baby boomers will already have occurred. Yet there’s no crisis.

There is, however, a different issue with low population growth. To maintain full employment, a market economy must persuade businesses to invest all the money households want to save. Yet a lot of investment demand is driven by population growth, as new families need newly built houses, new workers require the construction of new office buildings and factories, and so on.

So low population growth can cause persistent spending weakness, a phenomenon diagnosed in 1938 by the economist Alvin Hansen, who awkwardly dubbed it “secular stagnation.” The term and concept have been revived recently by Larry Summers, and on this issue I think he’s right.

Secular stagnation can be a problem, because if interest rates are very low even in good times there’s not much room for the Fed to cut rates during recessions. But a low-interest-rate world can also offer major policy opportunities — if we’re willing to think clearly.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 13, 2021 at 11:55am

-

Remittances to #Pakistan from overseas #Pakistanis jump 34% to $2.5 billion in May 2021. #Remittances climbed to an all-time high in 11 months of this fiscal year. Remittances surged 29.4% to $26.7 billion in July-May FY2021. #economy #diaspora

https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/847709-remittances-rise-34pc-to-2-...

Remittances by overseas Pakistanis increased 34 percent year-on-year to $2.5 billion in May, staying above the $2 billion mark for a year, the central bank’s data showed on Thursday.

However, the remittances fell 10.4 percent in May from April “This fall was expected as remittances usually slow in the post Eid-ul-Fitr period,” the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) said in a statement. As Eid fell in mid-May with markets closed a week earlier, there was some front-loading of remittances in April, it said. The usual post-Eid monthly dip was much smaller this year.

The seasonal decline in May less than half the average decline observed during FY2016-2019. In FY2020, remittances experienced an exceptional rise due to the easing of COVID lockdowns in the post-Eid period in Gulf countries, said the SBP.

Remittances climbed to an all-time high in 11 months of this fiscal year. Remittances surged 29.4 percent to $26.7 billion in July-May FY2021. These inflows during the first eleven months of FY2021 have already crossed the full FY2020 level by $3.6 billion.

Most remittance inflows came from Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US). Remittances sourced from Saudi Arabia rose 19.5 percent to $7 billion in July-May FY2021.

From UAE, remittances increased 9.7 percent $5.6 billion. Pakistan received $3.7 billion in remittances from the UK in 11 months compared with $2.2 billion in the same period of last fiscal year.

Remittances from the U.S. increased 58 percent to $2.5 billion.

Record high inflows of workers’ remittances were driven by policy measures by the government and SBP to incentivise the use of formal channels, curtailed cross-border travel in the face of COVID-19, altruistic transfers to Pakistan amid the pandemic, and orderly foreign exchange market conditions, the SBP said.

Global air travel was far below the comparable 2019 levels, and therefore emigrants are likely to have continued to utilize the banking channels to support their families back home. Within Pakistan, policy measures undertaken by the government and the SBP to encourage inflows through formal means also contributed to the growth in remittances. Furthermore, continued policy support in the host destinations (especially the advanced economies) via unemployment benefits, rent and loan deferrals, and direct cash handouts, likely increased the ability of migrants to remit higher amounts back home. Also, the efforts by global money transfer operators and governments to incentivize migrants to adopt digital channels to remit funds have likely also played a role in pushing up inflows received via the banking system.

In Pakistan also, banks are being incentivised to introduce digital products to facilitate migrants in sending remittances under the Pakistan Remittance Initiative. Data shows that transaction volumes and amounts of international remittance transactions in Pakistan via the branchless banking mode (m-wallets) have grown quite strongly since the Covid-19 outbreak. Remittance flows are expected to remain strong on the back of continued surge in inflows across all the major corridors and the welcome turnaround in the trend of Pakistanis going abroad for work.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 13, 2021 at 4:45pm

-

The number of international migrants reaches 272 million, continuing an upward trend in all world regions, says UN

17 September 2019, New York

https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/internationa...

Increase in global number of international migrants continues to outpace growth of the world’s population

The number of international migrants globally reached an estimated 272 million in 2019, an increase of 51 million since 2010. Currently, international migrants comprise 3.5 per cent of the global population, compared to 2.8 per cent in the year 2000, according to new estimates released by the United Nations today.

The International Migrant Stock 2019, a dataset released by the Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) today, provides the latest estimates of the number of international migrants by age, sex and origin for all countries and areas of the world. The estimates are based on official national statistics on the foreign-born or the foreign population obtained from population censuses, population registers or nationally representative surveys.

Mr. Liu Zhenmin, UN Under-Secretary-General for DESA, said that “These data are critical for understanding the important role of migrants and migration in the development of both countries of origin and destination. Facilitating orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people will contribute much to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

In 2019, regionally, Europe hosts the largest number of international migrants (82 million), followed by Northern America (59 million) and Northern Africa and Western Asia (49 million).

At the country level, about half of all international migrants reside in just 10 countries, with the United States of America hosting the largest number of international migrants (51 million), equal to about 19 per cent of the world’s total. Germany and Saudi Arabia host the second and third largest numbers of migrants (13 million each), followed by the Russian Federation (12 million), the United Kingdom (10 million), the United Arab Emirates (9 million), France, Canada and Australia (around 8 million each) and Italy (6 million).

Concerning their place of birth, one-third of all international migrants originate from only ten countries, with India as the lead country of origin, accounting for about 18 million persons living abroad. Migrants from Mexico constituted the second largest “diaspora” (12 million), followed by China (11 million), the Russian Federation (10 million) and the Syrian Arab Republic (8 million).

The share of international migrants in total population varies considerably across geographic regions with the highest proportions recorded in Oceania (including Australia and New Zealand) (21.2%) and Northern America (16.0%) and the lowest in Latin America and the Caribbean (1.8%), Central and Southern Asia (1.0%) and Eastern and South-Eastern Asia (0.8%).

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 13, 2021 at 4:46pm

-

The number of international migrants reaches 272 million, continuing an upward trend in all world regions, says UN

17 September 2019, New York

https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/internationa...

Most international migrants move between countries located within the same region. A majority of international migrants in sub-Saharan Africa (89%), Eastern and South-Eastern Asia (83%), Latin America and the Caribbean (73%), and Central and Southern Asia (63 %) originated from the region in which they reside. By contrast, most of the international migrants that lived in Northern America (98%), Oceania (88%) and Northern Africa and Western Asia (59%) were born outside their region of residence.

Forced displacements across international borders continues to rise. Between 2010 and 2017, the global number of refugees and asylum seekers increased by about 13 million, accounting for close to a quarter of the increase in the number of all international migrants. Northern Africa and Western Asia hosted around 46 per cent of the global number of refugees and asylum seekers, followed by sub-Saharan Africa (21%).

Turning to the gender composition, women comprise slightly less than half of all international migrants in 2019. The share of women and girls in the global number of international migrants fell slightly, from 49 per cent in 2000 to 48 per cent in 2019. The share of migrant women was highest in Northern America (52%) and Europe (51%), and lowest in sub-Saharan Africa (47%) and Northern Africa and Western Asia (36%).

In terms of age, one out of every seven international migrants is below the age of 20 years. In 2019, the dataset showed that 38 million international migrants, equivalent to 14 per cent of global migrant population, were under 20 years of age. Sub-Saharan Africa hosted the highest proportion of young persons among all international migrants (27%), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean, and Northern Africa and Western Asia (about 22% each).

Three out of every four international migrants are of working age (20-64 years). In 2019, 202 million international migrants, equivalent to 74 per cent of the global migrant population, were between the ages of 20 and 64. More than three quarters of international migrants were of working age in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, Europe and Northern America.

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Pakistan Pharma Begins Domestic Production of GLP-1 Weight Loss Drugs

Several Pakistani pharmaceutical companies have started domestic production of generic versions of GLP-1 (Glucagon-Like Peptide-1) drugs Ozempic/Wegovy (Semaglutide) and Mounjaro/Zeptide (Tirzepatide). Priced significantly lower than the branded imports, these domestically manufactured generic drugs will increase Pakistanis' access and affordability to address the obesity crisis in the country, resulting in lower disease burdens and improved life quality and longer life expectancy. Obesity…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on December 19, 2025 at 10:00am — 1 Comment

WIR 2026: Income and Wealth Inequality in India, Pakistan and the World

The top 1% of Indians own 40.1% of the nation's wealth, higher than the 37% global average. This makes India one of the world's most unequal countries, according to the World Inequality Report. By contrast, the top 1% own 24% of the country's wealth in Pakistan, and 23.9% in Bangladesh. Tiny groups of wealthy elites (top 1%) are using their money to buy mass media to manipulate public opinion for their own benefit. They are paying politicians for highly favorable laws and policies to further…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on December 15, 2025 at 1:00pm — 8 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network