INDIA CLOCKS IN AT 7.4 PER CENT REAL GDP GROWTH AND IS NOW THE WORLD’S FASTEST GROWING BRIC ECONOMY!

*cough*

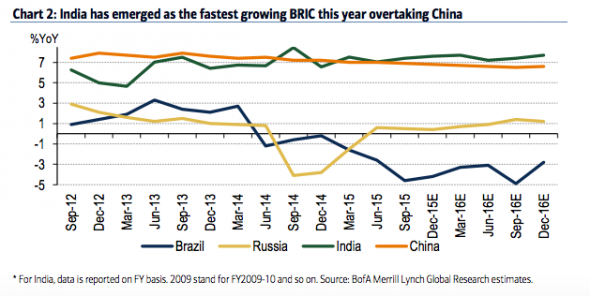

Sorry. Got carried away by charts like this one from BofAML:

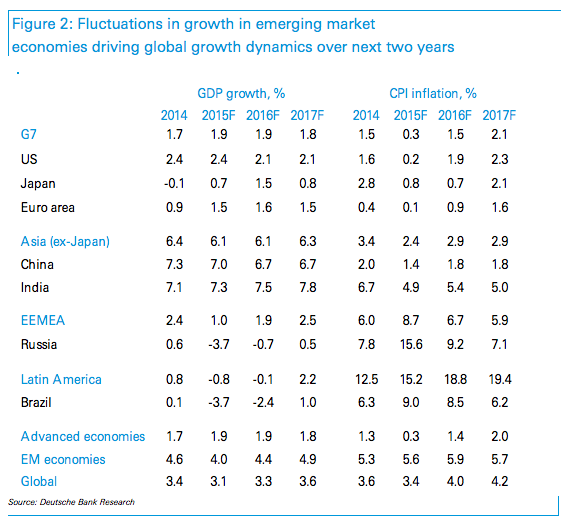

Or this one from Deutsche that has India growing at 7.8 per cent in 2017 (with inflation running at a v decent 5 per cent):

Thing is, and as we’ve written before, there is still a lack of confidence in India’s recently updated economic growth series showing up in our inboxes even as the room for caveats in the media gets increasingly squeezed — the validity of such stats tend to be less relevant when they’re telling a positive story, no?

Anyway, here’s BNP Paribas’ Richard Iley giving the scepticism some welcome space a little while ago: “The turn in the capex cycle is still tentative, a number of key indicators, such as credit growth, still signal relatively sluggish growth momentum and the rebasing of India’s national accounts, which has lifted GDP growth, continues to be taken with at least a pinch of salt.”

And here’s a few more up to date paragraphs from Macquarie, which dropped after the most recent print at the end of November (our emphasis):

Notwithstanding the reported real GDP growth numbers, a common question that we keep getting from investors is whether the Indian economy is actually growing above the 7% mark when essentially it still feels around 6% looking at the onground reality and global situation…

The good …: As we have been highlighting, there are some green shoots emerging, especially on the public capex front and urban consumption. There have been policy efforts over the past few months to revive projects in the roads, railways, mining and power sectors by (a) easing investment bottlenecks, including facilitating environmental and forest clearances, ensuring coal availability, steps toward labour market reforms, etc; (b) a cumulative 125bp cut in policy rates; and (c) encouraging capex spending by cash-rich PSUs. We believe these have helped to provide a bounce in investment activity picking up on a low base. Similarly, the upcoming revision in salaries under the 7th PC (link) effective Jan-16 contained inflationary pressures and subdued global commodity prices that will help support private consumption over the coming months, especially in urban areas.

… and the bad: The corporate earnings downgrade cycle continues, with the street having downgraded Nifty estimates by around 15–17% since the beginning of the year. Bank credit growth remained sluggish at 9.3% YoY for the Sept-15 quarter. Banking sector pressure continues, with nearly 13–15% of the book being stressed. Private corporate capex is yet to bounce back meaningfully, and rural consumption has slowed significantly, led by weak monsoons and curtailment in government spending. A weak global economy, too, is holding back capacity utilisation in the manufacturing sector and exports.

But even leaving all of that high frequency, real economy, stuff aside, one glaring problem in this new GDP series appears to lie in the deflator — the inflation measure used to convert estimates of nominal GDP into real, inflation-adjusted terms and which will cue China comparison klaxons. More particularly, it lies in the services deflator.

Here’s SocGen’s India economist Kunal Kumar Kundu:

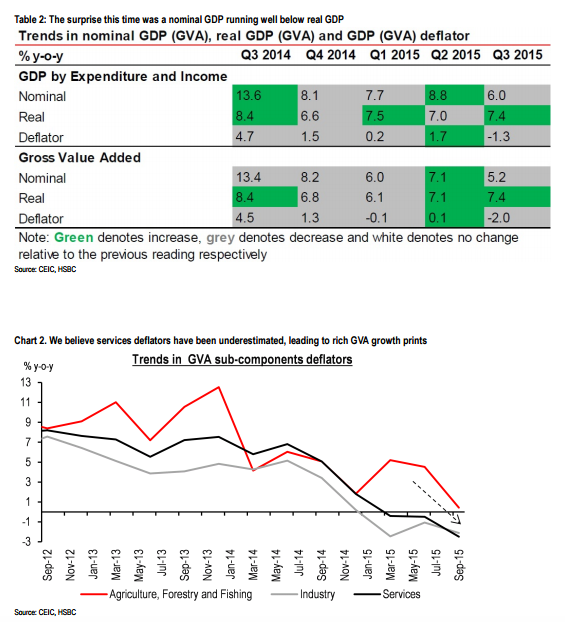

Even as most analysts have focused on India’s better than expected real economic growth (7.4% yoy for both gross value added, or GVA, and GDP), many have failed to notice the remarkably low growth in nominal terms (5.2% for GVA [Ed - GVA + taxes on products - subsidies on products = GDP] and 6.0% for GDP), as we noted here. The culprit was the deflator, as it indicated a worrying deflationary tendency…

The really interesting/ dodgy thing here is that, as HSBC say, growth in the services deflator, which is infamous for high and sticky prices, was actually running below the industry deflator. Which is “odd because manufacturing and industry at large should be the prime beneficiaries of falling commodity prices and as such should run below services (which is largely non-tradable) inflation”:

The suspicion is that deflators have been underestimated because the services deflator has been pegged more to the wholesale price index than to the consumer price index. And, er, it’s not a component in the India WPI basket.

From Kumar Kundu again:

For India, the bigger challenge is the deflator method that is followed for the service sector. While manufacturing is part of the WPI (and the GVA manufacturing deflator unsurprisingly follows WPI-manufacturing), services are not. Yet, the GDP service sector deflator mimicking the WPI raises a fundamental question as to how a component that does not exist in the WPI basket can be deflated by WPI.

With services accounting for about 60% of the GVA, the type of deflator used becomes crucial. Using the deflator method, services have seemingly been in deflation for three continuous quarters, including inflation of -2.5% yoy during Q3 2015. On the other hand, India’s service sector inflation, which has only recently been included in the country’s national CPI, remains positive, with an increasing divergence away from the GVA service sector deflator.

And HSBC say that “Correcting the CPI/WPI ratio since the start of the new national accounts series, we find that on average GVA deflators may be underestimated by over 100bp and therefore real GVA growth could possibly be overestimated by around the same amount.”

It’s a pretty obvious contrast between the new and old methods of measurement when charted:

No-one is saying there is anything particularly sinister behind this confusion, even if said confusion extends beyond the deflator. Nor should the actual level of economic growth, versus the effect of that growth, be given undue importance. It’s just… confusing. For everyone, including the RBI.

Which is perhaps appropriate considering the size and lack of development of India’s economy — somewhere around half of India’s GDP and 90 per cent of it’s employment are informal, so GDP reporting isn’t the easiest task. As Credit Suisse wrote in a previous note, “Unlike in the developed economies where informality is purely a deliberate choice to avoid taxation or regulations, in India it is more structural: a reflection of the lack of development and limited government reach.”

But, if you’re feeling less kind… here’s Kumar Kundu one more time:

With the new GDP series continuing to raise more questions…. than it answers, continuing with the WPI as the method of deflating the economy further adds to the poor quality of data. It is no coincidence that the RBI has started to focus on CPI and not WPI as a more important variable in monetary policy action. India’s Central Statistical Organisation (CSO) clearly has a lot more questions to answer.

More so, you’d hope that high headline growth rates don’t distract from the need for reform and legislation in an country that needs to generate something like 1m jobs a month to take advantage of its demographic dividend – or to put it even more starkly, India is where almost one in five of all global jobs must be created in the next several decades.

Hard to spot acknowledgment of that urgency in India’s parliament at the moment.

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network