PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Misery Index: Who's Less Miserable? India or Pakistan?

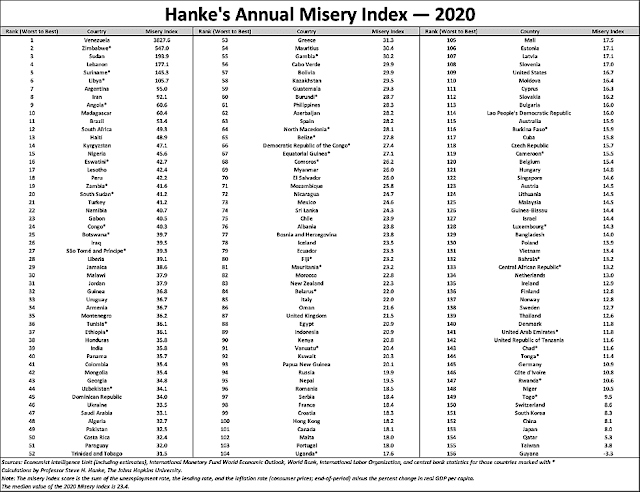

Pakistanis are less miserable than Indians in the economic sphere, according to the Hanke Annual Misery Index (HAMI) published in early 2021 by Professor Steve Hanke. With India ranked 49th worst and Pakistan ranked 39th worst, both countries find themselves among the most miserable third of the 156 nations ranked. Hanke teaches Applied Economics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Hanke explains it as follows: "In the economic sphere, misery tends to flow from high inflation, steep borrowing costs, and unemployment. The surefire way to mitigate that misery is through economic growth. All else being equal, happiness tends to blossom when growth is strong, inflation and interest rates are low, and jobs are plentiful". Several key global indices, including misery index, happiness index, hunger index, food affordability index, labor force participation rate, ILO’s minimum wage data, all show that people in Pakistan are better off than their counterparts in India.

Hanke's Misery Index:

Hanke's Annual Misery Index (HAMI) ranks Pakistan 49th (32.5) and India 39th (35.8) most miserable for year 2020. Bangladesh is significantly better than both India and Pakistan with a misery index of 14 and rank of 129. Venezuela ranks number 1 as the world's most miserable country followed by Zimbabwe 2nd, Sudan 3rd, Lebanon 4th and Suriname 5th among 156 countries ranked this year. The rankings for the two South Asian nations are supported by other indices such as the World Bank Labor Participation data, International Labor Organization Global Wage Report, World Happiness Report, Food Affordability Index and Global Hunger Index.

|

| Hanke's Annual Misery Index 2021. Source: National Review |

Employment and Wages:

Labor force participation rate in Pakistan is slightly above 50% during this period, indicating about 2% drop in 2020. Even before COVID pandemic, there was a steep decline in labor force participation rate in India. It fell from 52% in 2014 to 47% in 2020.

|

| Labor Force Participation Rates in Pakistan (Top), India (bottom). ... |

The International Labor Organization (ILO) Global Wage Report 2021 indicates that the minimum wage in Pakistan is the highest in South Asia region. Pakistan's minimum monthly wage of US$491 in terms of purchasing power parity while the minimum wage in India is $215. The minimum wage in Pakistan is the highest in developing nations in Asia Pacific, including Bangladesh, India, China and Vietnam, according to the International Labor Organization.

|

| Monthly Minimum Wages Comparison. Source: ILO |

The impact on livelihoods of workers in developing nations during the COVID pandemic has varied depending on the size of the informal work forces, according to The Economist magazine.

|

| Workers in Informal Economy of Selected Developing Countries. Sourc... |

Most countries with large informal work forces have recovered but India's jobs crisis has only deepened since the start of the COVID19 pandemic. Latest CMIE data indicates that employment rate in India was just 37.34% in November, 2021.

|

| Asian Employment Rates. |

|

| History of Inflation in Pakistan. Source: Statista |

|

| Hunger Trends in South Asia. Source: Global Hunger Index |

Amid the COVID19 pandemic, Pakistan's World Happiness ranking has dropped from 66 (score 5.693) among 153 nations last year to 105 (score 4.934) among 149 nations ranked this year. Neighboring India is ranked 139 and Afghanistan is last at 149. Nepal is ranked 87, Bangladesh 101, Pakistan 105, Myanmar126 and Sri Lanka129. Finland retained the top spot for happiness and the United States ranks 19th.

|

| Pakistan Happiness Index Trend 2013-2021 |

One of the key reasons for decline of happiness in Pakistan is that the country was forced to significantly devalue its currency as part of the IMF bailout it needed to deal with a severe balance-of-payments crisis. The rupee devaluation sparked inflation, particularly food and energy inflation. Global food prices also soared by double digits amid the coronavirus pandemic, according to Bloomberg News. Bloomberg Agriculture Subindex, a measure of key farm goods futures contracts, is up almost 20% since June. It may in part be driven by speculators in the commodities markets. These rapid price rises have hit the people in Pakistan and the rest of the world hard. In spite of these hikes, Pakistan remains among the least expensive places for food, according to recent studies. It is important for Pakistan's federal and provincial governments to rise up to the challenge and relieve the pain inflicted on the average Pakistani consumer.

Pakistan's Real GDP:

Many economists believe that Pakistan’s economy is at least double the size that is officially reported in government's Economic Surveys. The GDP has not been rebased in more than a decade. It was last rebased in 2005-6 while India’s was rebased in 2011 and Bangladesh’s in 2013. Just rebasing the Pakistani economy will result in at least 50% increase in official GDP. A research paper by economists Ali Kemal and Ahmad Wasim of PIDE (Pakistan Institute of Development Economics) estimated in 2012 that the Pakistani economy’s size then was around $400 billion. All they did was look at the consumption data to reach their conclusion. They used the data reported in regular PSLM (Pakistan Social and Living Standard Measurements) surveys on actual living standards. They found that a huge chunk of the country's economy is undocumented.

Pakistan's service sector which contributes more than 50% of the country's GDP is mostly cash-based and least documented. There is a lot of currency in circulation. According to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the currency in circulation has increased to Rs. 7.4 trillion by the end of the financial year 2020-21, up from Rs 6.7 trillion in the last financial year, a double-digit growth of 10.4% year-on-year. Currency in circulation (CIC), as percent of M2 money supply and currency-to-deposit ratio, has been increasing over the last few years. The CIC/M2 ratio is now close to 30%. The average CIC/M2 ratio in FY18-21 was measured at 28%, up from 22% in FY10-15. This 1.2 trillion rupee increase could have generated undocumented GDP of Rs 3.1 trillion at the historic velocity of 2.6, according to a report in The Business Recorder. In comparison to Bangladesh (CIC/M2 at 13%), Pakistan’s cash economy is double the size. Even a casual observer can see that the living standards in Pakistan are higher than those in Bangladesh and India.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Pakistan's Pharma Industry Among World's Fastest Growing

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid1...

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Cou...

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

Democracy vs Dictatorship in Pakistan

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

Panama Leaks in Pakistan

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 1, 2021 at 10:35am

-

#Pakistan elected G77 chair, seeks #debt restructuring & allocation of more resources for developing nations to rejuvenate the post-#COVID global #economy. G77 plus #China is a loose alliance of developing countries established on June 15, 1964. https://www.dawn.com/news/1661335

Pakistan is a founding member and Tuesday’s election was held by acclamation.

Addressing the group's 45th annual meeting at the United Nation's headquarters in New York, Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi urged developing nations to promote a common development agenda to return to the path of sustained and sustainable growth.

As the new chair, "Pakistan hopes to collaborate with members of the group to promote a common development agenda for developing countries that includes debt restructuring, redistribution of the 650 billion new special drawing rights (SDR) to developing countries, and larger concessional financing,” Qureshi said.

SDRs are supplementary foreign exchange reserve assets defined and maintained by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The minister also called for the mobilisation of the $100 billion in annual climate finance by developed countries, ending the billions in illicit financial flows from developing countries and the return of their stolen assets.

Qureshi also underlined the need for creating an equitable and open trading system along with a fair international tax regime.

The primary goals of the G77 are to maintain the independence and sovereignty of all developing countries, to defend the economic interests of member states by insisting on equal standing with developed countries in the global marketplace.

It also seeks to establish a united front on issues of common concern, and to strengthen ties between member countries.

As a founding member, Pakistan has contributed consistently to the shared objectives and interests of the group and has had the distinct privilege to chair the group in New York on three occasions in the past.

Qureshi reminded the international community that the world was facing a triple challenge: the Covid-19 pandemic and its consequences, the realisation of sustainable development goals (SDGs) and climate change.

He pointed out that the pandemic and climate change have had a disproportionate impact on developing countries and reversed their progress towards achieving the SDGs by 2030.

Qureshi noted that rich nations had injected over $26 trillion to stimulate their economies and recover from the Covid-19 crisis but “the developing countries have been unable to mobilise even a fraction of the $3-4 trillion they need for economic recovery”.

Noting that the developing world was home to 80 per cent of the world's population, he warned that the disruption of supply chains, and the revived demand in developed economies, had triggered global inflation, compounded the plight of the poor and complicated the debt and liquidity problems of the developing countries.

“Unless the challenges confronting developing countries are addressed and overcome, the world economy will not be able to return to the path of sustained and sustainable growth,” he said. “Islands of prosperity cannot co-exist within an ocean of poverty.”

"The world economy will not succeed in overcoming these challenges, unless developing countries generate adequate financial support to address their debt," Qureshi said, calling for an equitable financial and trade architecture.

“Developing countries need to promote a common development agenda to return to the path of sustained and sustainable growth,” he said.

“Pakistan believes that notwithstanding their current challenges, the greatest potential for economic growth is in the developing world but first it must set out the parameters for equitable global growth and development and realise the promise of a more equal and inclusive world,” he said.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 1, 2021 at 11:09am

-

India reported 8.4% growth in July-to-September up from -7.4% last year. #India’s #MiddleClass Anxious & Frugal. #COVID19 has robbed the country of more than a year of badly needed economic growth. That’s lost ground that cannot be regained quickly. #BJP https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/30/business/india-economy-gdp.html?...

India’s vaccination campaign has helped put the economy back on track. Ms. Kishore forecast growth of 7.8 percent next year, about 2.5 percentage points higher than what it was in 2019. Still, that would leave 2022 output 9 percent lower than she had forecast before the pandemic struck.

-----------

NEW DELHI — India’s economy is limping back to life, and its wealthy consumers are finally returning to its malls and stores.

But at Electronics Desire, where the aisles are empty and the sales are slow, the lingering fears of India’s middle class — and the millions who aspire to join them someday — are on full display.

An appliances shop in Ramphal Chowk, a middle-class neighborhood in the New Delhi suburb of Dwarka, Electronics Desire is struggling through its weakest sales in months. Even last year, when a coronavirus lockdown at one point brought the economy to a virtual standstill, sales were better, said Tejendar Singh, the manager.

“Around this time last year we sold 15 to 20 dishwashers,” said Mr. Singh, explaining how customers bought the appliances to keep their maids, and potential Covid-19 infections, out of their homes. “This time, we couldn’t even sell two units.”

On Tuesday, India on paper reported a big jump in growth, of 8.4 percent, in the July-to-September period compared with a contraction of 7.4 percent for the same period a year earlier. But that heady number conceals lingering damage from Covid-19 to an economy that needs to generate a steady number of jobs to keep its young, vast population content. The country’s two waves since early last year have killed hundreds of thousands of people, pushed millions into poverty and robbed the country of more than a year of badly needed growth.

Compared with two years ago, before the coronavirus struck, economic output was 4 percentage points higher, according to the Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation. Even that figure reflects pent-up demand rather than a healthy rise in gross domestic product, said Priyanka Kishore, the head of India and Southeast Asia for Oxford Economics, a research firm.

“If we talk about the structural hits and the G.D.P. level compared to pre-Covid baselines, it’s still 10 percent or so lower,” she said.

The weak and uneven recovery is putting pressure on Prime Minister Narendra Modi to do something about growth. It is also putting renewed focus on longer-term problems that were weighing down India’s economy even before the pandemic: slowing demand, a manufacturing sector struggling to take off and shrinking labor participation.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 2, 2021 at 4:16pm

-

India’s population will start to shrink sooner than expected

For the first time, Indian fertility has fallen below replacement level

https://www.economist.com/asia/2021/12/02/indias-population-will-st...

When something happens earlier than expected, Indians say it has been “preponed”. On November 24th India’s health ministry revealed that a resolution to one of its oldest and greatest preoccupations will indeed be preponed. Some years ahead of un predictions, and its own government targets, India’s total fertility rate—the average number of children that an Indian woman can expect to bear in her lifetime—has fallen below 2.1, which is to say below the “replacement” level at which births balance deaths. In fact it dropped to just 2.0 overall, and to 1.6 in India’s cities, says the National Family Health Survey (nfhs-5), a country-wide health check. That is a 10% drop from the previous survey, just five years ago.

------------

Slowing growth will reduce long-term pressure on some resources that are relatively scarce in India, such as land and water. The news may have other benefits, too. Politicians have often used fear of population growth to rally votes, typically by accusing “a particular community”—a circumlocution referring to India’s 15% Muslim minority—of having too many babies. Narendra Modi, the prime minister, has warned of a looming population explosion. Members of his Bharatiya Janata Party (bjp) have even called for limits to family size. In July legislators in bjp-controlled Uttar Pradesh proposed a law that would deny government services to families with more than two children.

------------

The Indian government’s new numbers may curtail these execrable suggestions. Fertility among Indian Muslims is generally higher than among Hindus. This is in part because so many are poor. But the difference has steadily narrowed; between 2005 and 2015 the fertility rate among Indian Muslims dropped from 3.4 to 2.6. Data on religion have yet to be parsed from the latest survey, but the fertility rates it shows for India’s only two Muslim-majority territories, the Lakshadweep Islands and Jammu & Kashmir, are far below replacement level and among the lowest in India, at 1.4.

While a declining fertility rate is broadly a sign that India is richer and better educated than before, it will also bring worries. Economists have long heralded the “demographic dividend”, when productivity rises because a bigger slice of the population pyramid is of working age. This window will now be narrower, and India will have to contend sooner with a fast-growing proportion of elderly people to care for.

Stark discrepancies in fertility rates between states also carry dangers. In future more Indians from the crowded north will seek jobs in the richer and less fecund south. Politicians will also face the hot issue of how to allot parliamentary constituencies. Back in 1971 Mrs Gandhi froze the distribution of seats among states. The result is that whereas an mp from Kerala now represents some 1.8m constituents, one from Uttar Pradesh represents nearly 3m. When the freeze on redistricting lifts some time in the next decade, these disparities will spawn a big fight.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 4, 2021 at 7:12am

-

Advisor to Minister on Finance and Revenue Shaukat Tarin moved to pacify the public, saying that the country’s economy is moving in the right direction and the widening trade gap would narrow in the coming months, a statement that comes after Pakistan reported a historic high import bill in November.

https://pakobserver.net/tarin-for-patience-as-economy-moving-in-rig...

Speaking to the media on Friday alongside Adviser to Prime Minister on Commerce Abdul Razak Dawood, Tarin said the public needs to be patient, adding that there is hope that international commodity prices will come down, which would reduce the import bill.

“Economic indicators are moving in the right direction,” said Tarin.

Talking about fundamentals, the advisor said that the tax revenue has increased by 36% year-on-year, a development, he said points to a growing economy.

“The revenue is growing, electricity consumption has increased, and agricultural output has also improved,” he said.

“What we need to see is that all the economic indicators are moving in the right direction. This is a temporary phenomenon (spike in global prices), which is prevalent across the globe including India, US, and UK. We too, will get out of it.”

Referring to the Pakistan Stock Exchange’s (PSX) sell-off the previous day, the advisor said that the media gives “more coverage to negative developments”. “We need to be a little patient, commodity prices in the international market will decline soon.”

Tarin asks provinces to ensure availability of flour in market Meanwhile, talking about inflation that hit a 21-month high at 11.5% in November, Tarin called it ‘imported inflation’.

Tarin said that the positive development is that Pakistan’s exports are increasing, and “hopefully, our remittances and exports together would shrink our trade gap”.

Speaking on the hike in commodity prices, the advisor said that the government is seeing a return of stability in coal and oil prices.

Dawood, the advisor on commerce, said Pakistan’s high import bill was mainly on account of energy and raw-materials.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 4, 2021 at 7:43am

-

Kaushik Basu (Professor of Economics, Cornell University, and former Chief Economist of the World Bank)

@kaushikcbasu

India's growth of 8.4% over Jul-Sep is welcome news. But it'll be injustice to India if we don't recognize, when this happens after -7.4% growth, it means an annual growth of 0.2% over 2 years. This is way below India's potential. India has fundamental strength to do much better.https://twitter.com/kaushikcbasu/status/1466619562435170304?s=20

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 12, 2021 at 2:08pm

-

ExplainSpeaking: How policymakers in UP, rest of India are underestimating the unemployment crisis

Merely looking at the traditional metric of the unemployment rate is misleading. Here’s why policymakers should look at ‘employment rate’ if they want to accurately assess the scale of joblessness

https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/uttar-pradesh-jobs-indi...

--------------------

In India, as the virus abates, a hunger crisis persists

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/12/06/india-hunger-corona...

“The hunger crisis is, in fact, fundamentally reflective of the livelihood crisis,” said Jayati Ghosh, a development economist. People do not have money to buy food, she said, and “that’s both our employment and food systems failing.”

The unemployment rate in April to June of 2020, at the height of the first lockdown, was nearly 21 percent in urban areas, according to government figures. Even as the economy showed signs of revival this year, 15 million jobs were lost in May when a devastating second wave killed hundreds of thousands and brought the health-care system to near collapse.

Nearly 80 percent of India’s workforce makes a living in the informal sector, which economists say was the worst hit. The problem is more pronounced in urban areas like Mumbai, where such workers subsist on their daily income for survival and lack networks or resources such as agricultural land in their home villages.

Sonawane’s work and life came to a sudden halt with the two lockdowns. The five jobs she worked — cleaning and cooking at upscale homes in the high-rise buildings visible from her cramped shanty — disappeared immediately.

Her husband, who worked as a delivery person for a gas company, stayed home. So did her three children, including her youngest son, 7, who would repeatedly ask her in the early days when school would reopen. Now, she said, he has forgotten much of what he had learned, as primary schools in the city have remained shut since the initial closures in March 2020.

After the lockdowns were lifted, Sonawane went back to work. But the world outside had changed.

Two of the families she worked for had left the city, and another told her not to return over coronavirus concerns. Her pre-pandemic income of $160 a month shrank by half. Her husband’s company laid him off.

“We never had food shortages at home” before this, Sonawane said. “We always earned enough to feed the family.”

Right to food

India’s food security law aims to provide free or subsidized food grains to two-thirds of the country’s population, making it the largest safety net in the country. But experts say gaps, its reliance on biometric authentication and a narrow scope have hindered its efficacy.

During the lockdown, the government expanded benefits by providing an extra five kilograms (about 11 pounds) of rice or wheat every month to those eligible, a program that was recently extended to March 2022.

But economists say the law’s coverage needs to account for the increase in population over the past decade, which could bring an additional 100 million people under its purview.

Not far from Chembur, where Sonawane lives, is the working-class neighborhood of Govandi, framed by the country’s largest landfill. In one of the narrow streets is the home of 31-year-old Farhan Ahmad, a father of two, who worked as a driver and is one of the millions of migrants who have fallen through the cracks in the food law.

The five years before the pandemic had been good for Ahmad, who had moved to Mumbai from his village hoping to make a life in the city.

Ahmad signed up to drive with Ola, an Indian multinational ride-hailing company, when a friend lent him a car if he agreed to pay back the loan on it. By the time the coronavirus arrived, he had a small sum set aside in savings. He and his wife debated buying a refrigerator.

“Forget about affording a fridge now,” said Ahmad. “On most days I can’t buy enough food.”

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 13, 2021 at 6:07pm

-

Center for Monitoring Indian Employment (CMIE)

Indian Employment data disappoints in November 2021

https://unemploymentinindia.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=wtabnav...

Headline data on employment in November 2021 is mildly encouraging but the details underlying these are quite disappointing. The encouraging signs are that the unemployment rate declined from 7.8 per cent in October to 7 per cent in November; the employment rate rose by a whisker from 37.28 per cent to 37.34 per cent. This translated into employment increasing by 1.4 million, from 400.8 million to 402.1 million in November 2021.

The first disappointment in the November data is that the labour participation rate (LPR) has slipped. It fell from 40.41 per cent in October to 40.15 per cent in November. This is the second consecutive month of a fall in the LPR. Cumulatively, the LPR has fallen by 0.51 percentage points over October and November 2021. This makes it a significant fall in the LPR compared to average changes seen in other months if we exclude the months of economic shock such as the lockdown.

The fall of October and November seems to suggest that the recovery in the LPR from its recent drop to 39.6 per cent in June 2021 following the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic has run out of steam. And, a secular decline may set in again. This is what had happened after the recovery from the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. LPR crashed from nearly 43 per cent before the first wave of Covid-19 to about 36 per cent. It recovered quickly to 41 per cent and then lost steam. Then, it started sliding slowly to hover just above 40 per cent before the second wave dragged it below 40 per cent during the quarter ended June 2021. The LPR recovered steadily in the second quarter of the fiscal to reach 40.7 per cent by September 2021. But then it slid back to 40.4 per cent in October and then to 40.2 per cent in November.

The two pandemic shocks have lowered the LPR structurally. And, the declining trend has continued at the lowered levels. India now has an LPR which is close to 40 per cent compared to about 43 per cent before the pandemic.

India’s LPR is much lower than global levels. According to the World Bank, the modelled ILO estimate for the world in 2020 was 58.6 per cent

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 13, 2021 at 6:13pm

-

Center for Monitoring Indian Employment (CMIE)

Indian Employment data disappoints in November 2021

https://unemploymentinindia.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=wtabnav...

India’s LPR is much lower than global levels. According to the World Bank, the modelled ILO estimate for the world in 2020 was 58.6 per cent (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.ZS). The same model places India’s LPR at 46 per cent. India is a large country and its low LPR drags down the world LPR as well. Implicitly, most other countries have a much higher LPR than the world average. According to the World Bank’s modelled ILO estimates, there are only 17 countries worse than India on LPR. Most of these are middle-eastern countries. These are countries such as Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Syria, Senegal and Lebanon. Some of these countries are oil-rich and others are unfortunately mired in civil strife. India neither has the privileges of oil-rich countries nor the civil disturbances that could keep the LPR low. Yet, it suffers an LPR that is as low as seen in these countries.

CMIE’s definition of employment and therefore of LPR is more stringent than what is recommended by the ILO. This definition informs that the LPR in India is much worse than what the international comparisons tell us. It is therefore a matter of greater concern than illustrated by an international comparison. Worse still, the LPR has been falling. The data for October and November tell us that it continues to fall even after the recent shocks that shaved off several percentage points off the LPR.

The second disappointment in the November data is also related to a structural damage in the trend seen in the employment data. Employment is falling in urban areas at a faster pace than in rural areas. As a result, the share of urban employment has been falling. During 2016-17 through 2018-19, urban employment accounted for 32 per cent of total employment in India. In 2019-20, the year just before the pandemic struck India, the share of urban employment dropped to 31.6 per cent. In 2020-21, it fell to 31.3 per cent. In November 2021, its share fell further to 31.2 per cent. In the first half of 2021-22, the share of urban employment was down to 31 per cent. There was an improvement in October to 31.5 per cent, but the rate has slid back to 31.2 per cent in November 2021, indicating continuing weakness in urban jobs.

Urban jobs arguably provide better wages and have a greater share of what are called the organised sectors. Their decline implies a decline in the overall quality of jobs in India.

In November 2021, while India generated 1.4 million additional jobs, its urban regions saw employment fall by 0.9 million. This was compensated by a 2.3 million increase in rural jobs.

A third and related disappointment in the November employment data is the fall in salaried jobs and a fall in the count of entrepreneurs. Salaried jobs fell by 6.8 million. Entrepreneurs declined by 3.5 million. These were compensated by an 11.2 million increase in employment among daily wage labourers and small traders. This again points to deterioration in the quality of employment. Salaried jobs, at 77.2 million, were 9.7 per cent lower in November 2021 than they were in November 2019.

Of all the disappointments in the employment data, the continuing fall in the LPR should be considered as the most worrisome.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 14, 2021 at 2:01pm

-

Budget 2021-22: Minimum wage increased from Rs17,500 to Rs20,000

Salaries and pensions increased by 10%

https://www.samaa.tv/money/2021/06/budget-2021-22-minimum-wage-incr...

The government has increased the minimum wage from Rs17,500 per month to Rs. 20,000.

Federal Finance Minister Shaukat Tarin on Friday presented the budget for the next financial year 2021-22.

Introducing the budget, the Finance Minister said that low-income earners have been affected more by inflation. In order to reduce the burden of inflation, the minimum wage has been increased from Rs. 17,500 to Rs20,000 per month.

The finance minister said that the salaries of government employees are being increased by 10% and the pensions of retired employees will be increased by 10% from July 1.

--------------

In purchasing power parity terms, one PPP US$ is equal to about PKR 40.

So Rs 20,000 per month minimum wage translates to $500 in PPP terms.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 24, 2021 at 7:22pm

-

India’s Stalled Rise: As the #COVID19 #pandemic spread in 2020, #India's #economy withered, shrinking by more than seven percent, the worst performance among major developing countries. Reversing a long-term downward trend, #poverty increased substantially https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2021-12-14/indias-sta...

INDIA’S LOST DECADE

To answer the question of whether India is back, it is important to first understand when and why India went away. The answer lies in plans that went badly wrong. During the boom years after the turn of the millennium, Indian firms invested heavily, on the assumption of continued rapid growth. So when the financial crisis brought the boom to an end, causing interest rates to soar and exchange rates to collapse, many large companies found it difficult to repay their debts. As companies began to default, banks were saddled with nonperforming loans, exceeding ten percent of their assets.

In response, successive governments launched initiative after initiative to address this “twin balance sheet” problem, initially asking banks to postpone repayments, later encouraging banks and firms to resolve their problems through an improved bankruptcy system. These measures gradually alleviated the debt problem, but they still left many firms too financially feeble to invest and banks reluctant to lend. And with lackluster investment and exports, the economy was unable to recover its former dynamism.

-------

As growth slowed, other indicators of social and economic progress deteriorated. Continuing a long-term decline, female participation in the labor force reached its lowest level since Indian independence in 1948. The country’s already small manufacturing sector shrank to just 13 percent of overall GDP. After decades of improvement, progress on child health goals, such as reducing stunting, diarrhea, and acute respiratory illnesses, stalled.

And then came COVID-19, bringing with it extraordinary economic and human devastation. As the pandemic spread in 2020, the economy withered, shrinking by more than seven percent, the worst performance among major developing countries. Reversing a long-term downward trend, poverty increased substantially. And although large enterprises weathered the shock, small and medium-sized businesses were ravaged, adding to difficulties they already faced following the government’s 2016 demonetization, when 86 percent of the currency was declared invalid overnight, and the 2017 introduction of a complex goods and services tax, or GST, a value-added tax that has hit smaller companies especially hard. Perhaps the most telling statistic, for an economy with an aspiring, upwardly mobile middle class, came from the automobile industry: the number of cars sold in 2020 was the same as in 2012.

--------

Adding to a decade of stagnation, the ravages of COVID-19 have had a severe effect on Indians’ economic outlook. In June 2021, the central bank’s consumer confidence index fell to a record low, with 75 percent of those surveyed saying they believed that economic conditions had deteriorated, the worst assessment in the history of the survey.

----------

Disaffection is also manifest in politics. The national government in New Delhi has been bickering with the country’s state governments for more than a year over the sharing of revenue from the GST. Several states have imposed new residency requirements on job seekers over the past two years, thus directly challenging the principle of a common national labor market. There has also been a revival of the policy of “reservation,” India’s version of affirmative action, in which some jobs are reserved for people from traditionally disadvantaged social groups.

Comment

- ‹ Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- Next ›

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

US-India Ties: Does Trump Have a Grand Strategy?

Since the dawn of the 21st century, the US strategy has been to woo India and to build it up as a counterweight to rising China in the Indo-Pacific region. Most beltway analysts agree with this policy. However, the current Trump administration has taken significant actions, such as the imposition of 50% tariffs on India's exports to the US, that appear to defy this conventional wisdom widely shared in the West. Does President Trump have a grand strategy guiding these actions? George…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on August 31, 2025 at 6:30pm — 5 Comments

Humbled Modi Reaches Out to China After Trump Turns Hostile

Prime Minister Narendra Modi appears to be shedding his Hindutva arrogance. He is reaching out to China after President Donald Trump and several top US administration officials have openly and repeatedly targeted India for harsh criticism over the purchase of Russian oil. Top American officials have accused India, particularly the billionaire friends of Mr. Modi, of “profiteering” from the Russian…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on August 24, 2025 at 9:00am — 7 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network