PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Pakistan's Total Education Spending Surpasses its Defense Budget

Pakistan's public spending on education has more than doubled since 2010 to reach $8.6 billion a year in 2017, rivaling defense spending of $8.7 billion. Private spending on education by parents is even higher than the public spending with the total adding up to nearly 6% of GDP. Pakistan has 1.7 million teachers, nearly three times the number of soldiers currently serving in the country's armed forces. Unfortunately, the education outcomes do not yet reflect the big increases in spending. Why is it? Let's examine this in some detail.

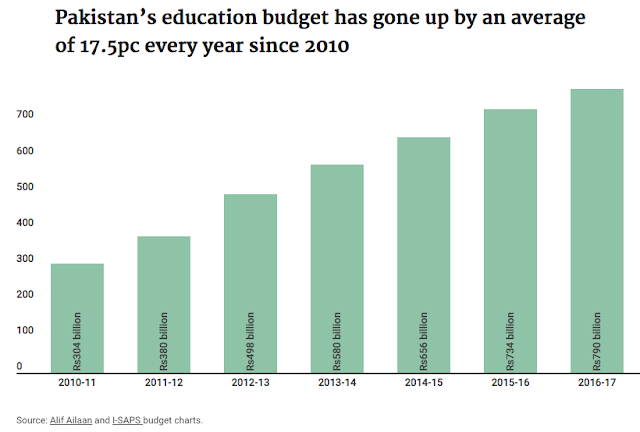

Pakistan Education Budget:

The total money budgeted for education by the governments at the federal and provincial levels has increased from Rs. 304 billion in 2010-11 to Rs. 790 billion in 2016-17, representing an average of 17.5% increase per year since 2010.

|

| Source: Dawn Newspaper |

Private Education Spending in Pakistan:

2012 Data from UNESCO and the World Bank shows that the private spending on education is about twice as much as the monies budgeted by federal and provincial governments in Pakistan.

Private/Public Spending on Education in Selected Countries. Source:... |

Education Outcomes:

UNESCO and World Bank data from 2013 shows that only 52% of Pakistani kids and 48% of Indian kids reached expected standard of reading after 4 years of school, according to the Economist Magazine. It also shows that 46% of Pakistani children dropped out of school before completing 4 years of education.

Reading Performance in Selected Countries. Source: Economist |

Education and Literacy Rates:

Pakistan's net primary enrollment rose from 42% in 2001-2002 to 57% in 2008-9 during Musharraf years. It has been essentially flat at 57% since 2009 under PPP and PML(N) governments.

Similarly, the literacy rate for Pakistan 10 years or older rose from 45% in 2001-2002 to 56% in 2007-2008 during Musharraf years. It has increased just 4% to 60% since 2009-2010 under PPP and PML(N) governments.

Pakistan's Human Development:

Human development index reports on Pakistan released by UNDP confirm the ESP 2015 human development trends.Pakistan’s HDI value for 2013 is 0.537— which is in the low human development category—positioning the country at 146 out of 187 countries and territories. Between 1980 and 2013, Pakistan’s HDI value increased from 0.356 to 0.537, an increase of 50.7 percent or an average annual increase of about 1.25.

Pakistan HDI Components Trend 1980-2013 Source: Human Development R... |

Overall, Pakistan's human development score rose by 18.9% during Musharraf years and increased just 3.4% under elected leadership since 2008. The news on the human development front got even worse in the last three years, with HDI growth slowing down as low as 0.59% — a paltry average annual increase of under 0.20 per cent.

Going further back to the decade of 1990s when the civilian leadership of the country alternated between PML (N) and PPP, the increase in Pakistan's HDI was 9.3% from 1990 to 2000, less than half of the HDI gain of 18.9% on Musharraf's watch from 2000 to 2007.

Bogus Teachers in Sindh:

In 2014, Sindh's provincial education minister Nisar Ahmed Khuhro said that "a large number of fake appointments were made in the education department during the previous tenure of the PPP government" when the ministry was headed by Khuhru's predecessor PPP's Peer Mazhar ul Haq. Khuhro was quoted by Dawn newspaper as saying that "a large number of bogus appointments of teaching and non-teaching staff had been made beyond the sanctioned strength" and without completing legal formalities as laid down in the recruitment rules by former directors of school education Karachi in connivance with district officers during 2012–13.

Ghost Schools in Balochistan:

In 2016, Balochistan province's education minister Abdur Rahim Ziaratwal was quoted by Express Tribune newspaper as telling his provincial legislature that “about 900 ghost schools have been detected with 300,000 fake registrations of students, and out of 60,000, 15,000 teachers’ records are unknown.”

Absentee Teachers in Punjab:

A 2013 study conducted in public schools in Bhawalnagar district of Punjab found that 27.5% of the teachers are absent from classrooms from 1 to 5 days a month while 3.75% are absent more than 10 days a month. The absentee rate in the district's private schools was significantly lower. Another study by an NGO Alif Ailan conducted in Gujaranwala and Narowal reported that "teacher absenteeism has been one of the key impediments to an effective and working education apparatus."

Political Patronage:

Pakistani civilian rule has been characterized by a system of political patronage that doles out money and jobs to political party supporters at the expense of the rest of the population. Public sector jobs, including those in education and health care sectors, are part of this patronage system that was described by Pakistani economist Dr. Mahbub ul Haq, the man credited with the development of United Nation's Human Development Index (HDI) as follows:

"...every time a new political government comes in they have to distribute huge amounts of state money and jobs as rewards to politicians who have supported them, and short term populist measures to try to convince the people that their election promises meant something, which leaves nothing for long-term development. As far as development is concerned, our system has all the worst features of oligarchy and democracy put together."

Summary:

Education spending in Pakistan has increased at an annual average rate of 17.5% since 2010. It has more than doubled since 2010 to reach $8.6 billion a year in 2017, rivaling defense spending of $8.7 billion. Private spending by parents is even higher than the public spending with the total adding up to nearly 6% of GDP. Pakistan has 1.7 million teachers, nearly three times the number of soldiers currently serving in the country's armed forces. However, the school enrollment and literacy rates have remained flat and the human development indices are stuck in neutral. This is in sharp contrast to the significant improvements in outcomes from increased education spending seen during Musharraf years in 2001-2008. An examination of the causes shows that the corrupt system of political patronage tops the list. This system jeopardizes the future of the country by producing ghost teacher, ghost schools and absentee staff to siphon off the money allocated for children's education. Pakistani leaders need to reflect on this fact and try and protect education from the corrosive system of political patronage networks.

Related Links:

History of Literacy in Pakistan

Reading and Math Performance in Pakistan vs India

Myths and Facts on Out-of-School Children

Who's Better For Pakistan's Human Development? Musharraf or Politic...

Corrosive Effects of Pakistan's System of Political Patronage

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 22, 2017 at 4:32pm

-

Should we double the education budget, or seek 100pc literacy?....Contd.

AHMAD ALI | NADIA NAVIWALAUPDATED JUN 07, 2017 01:47PM

Pakistan has doubled its budget in recent years, but enrollment has stagnated. As a result of the inefficient use of funds, access to quality education for children across the country stands compromised.https://www.dawn.com/news/1335342

In recent years, the federal and provincial governments have undertaken numerous reforms with varying levels of success. Despite their efforts, a lot remains to be done to get kids into school and improve learning in the classrooms.

To address these educational challenges, the efficient and effective use of the available budget for education is key.

Note: The defence budget does not include military pensions, the cost of the nuclear programme (estimated at $747 million by the Stimson Center), or military operations in FATA.

Since 2010, education has been a provincial responsibility. Hence, Pakistan's education budget is derived by summing up the federal and individual provincial budgets.

Provinces have allocated 17pc to 24pc of their budgets for education in 2016-17. (The provincial budgets for 2017-18 will be released in the coming weeks).

The ‘current budget’ is for salaries and operational costs (non-salary), whereas the ‘development budget’ is for the construction and rehabilitation of schools. Recent history suggests that provinces tend to under spend on development and non-salary budgets, but overspend on salaries, so that they end up utilising most of the education budget.

Unesco recommends that countries disburse 15pc to 20pc of their budgets on education. The global average is 14pc. Compared to its total national budget, Pakistan spends 13pc.

In Pakistan's case, this spending amounts to 2.83pc of the GDP on education. According to Alif Ailaan, an additional Rs400 billion on education is needed this year to increase spending to 4pc of GDP, bringing the education budget to Rs1.2 trillion.

Cutting a federal programme or collecting more taxes may help Pakistan towards that target. Cutting a federal programme or collecting more taxes may help Pakistan towards that target, but the dilemma of solving the education crisis will persist.

While Pakistan has doubled its budget and brought it closer to military spending, enrollment rates have stagnated.

Parents will send their kids to a private school, charging a few hundred rupees a month, if they can afford it. Nearly 40pc of students in Pakistan go to private schools. Their parents spend as much as the government does on education and tuition. If we add what Pakistani parents spend on education, Pakistan’s education spending exceeds 4pc of the GDP.

Children are out of school in Pakistan because they get so little out of going to school. Teachers are either absent, or present, but not teaching.

The 2015 report of the independent Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) finds that only 44pc of third graders in rural schools (public and private) can read a sentence in Urdu. Of those who stay in school through fifth grade, only 55pc can read a story in Urdu.

It is a similar story for science at a grade four level. In 2006, 67pc of students scored below average in the National Education Assessment System (NEAS) assessment of fourth grade science. The situation further deteriorated in 2014, when the most recent iteration of the NEAS assessment divulged that 79pc of students had scored below average.The majority of children aged five to nine in Pakistan are in school. That’s 17 out of 22 million kids, according to the National Education Management System. Improving literacy and numeracy rates for them is our best shot at convincing the parents of Pakistan’s five million out-of-school children aged five to nine that school is worth it.

Private school teachers are paid $25 to $50 per month. Government school teachers are paid $150 to $1,000 per month, according to a paper by SAHE and Alif Ailaan. Government school teachers have more education and training than private school teachers.

In light of the difference in teachers' salaries, private schools spend less than half of what the government does per child. However, according to LEAPS, children who go to private schools are one and a half to two grades ahead of those in government schools, depending on the subject.

The danger of increasing the budget without a plan is that it could all go into salaries for non-performing teachers, as has happened in Sindh.

Sindh’s budget has octupled (increased by a factor of 8x) since 2010.

Meanwhile the salary budget has gone up 12 times.

Pakistan is also inefficient at spending money set aside for building schools. The “development budget” that is allocated for this purpose goes unspent year after year.

Pakistan is under-performing even at its current budget levels. The solution is not dramatic budget increases, but making sure the budget we have is translating into schools where children are learning.

Instead of asking the government to double the budget, we should ask them to double the efforts for improving quality of learning for children who have been in school for years.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 26, 2017 at 5:41pm

-

#Pakistan's #Punjab province acts to improve #science content and correct #history in new revised school #textbooks. #education

by Pervez Hoodbhoy. https://www.dawn.com/news/1372660

The new books are cleanly printed on paper of decent quality, typographical errors are infrequent, and coloured cartoons show smiling girl children in class. Earlier textbooks typically showed docile boys facing grim-faced elderly teachers. My heart gladdened at suggested science experiments that are both interesting and doable. And, instead of beating the tired old drum of Muslim scientists from a thousand years ago, one now sees a genuine attempt to teach actual science — how plants grow and breathe, objects move, water makes droplets or freezes, etc.

On the history front one feels instant relief. Pakistan’s date of birth has thankfully been set at 1947 and away from 712 — the year Arab imperial conqueror Mohammed bin Qasim set foot in Sindh. Schoolbooks during Gen Ziaul Haq’s years contained this claim and no subsequent government dared to reset the clock. Astonishingly, one book frankly admits that Muslims had fought against other Muslims and ascribes the Mughal Empire’s downfall after Emperor Aurangzeb to his quarrelling sons rather than eternally scheming Hindu Rajputs.

But here’s the wonder of wonders: an Urdu translation of Quaid-i-Azam’s famous speech of Aug 11, 1947, has finally found its way into at least one social studies book! This declares that religion is a matter for the individual citizen and not of the state. The speech had hitherto been kept hidden for fear of polluting students’ minds and weakening the two-nation theory. Whether it will actually be covered in Matric examinations is difficult to say; if not then students and their teachers won’t take it seriously.

The older curriculum helped create a militant, intolerant mindset. A generation later, Pakistan saw jihad-obsessed youngsters emerging even from mainstream schools. Willing to kill and be killed, they are now everywhere and have to be crushed with Islamic-sounding operations like Zarb-i-Azb and Raddul Fasaad (for which great credit is claimed). Terrorist networks of students and teachers that target policemen, soldiers, and ordinary citizens have been discovered within many colleges and universities.

The eventual revamping of Punjab’s school textbooks owes to a belated realisation that thousands of Pakistani lives were needlessly lost to militancy fuelled by hate materials in textbooks. Many years will be needed for the new books to produce a more enlightened, less xenophobic generation. This welcome step needed to be taken sooner rather than later. I have no knowledge of the blacked-out province of Balochistan but Punjab’s bold move has not been matched by other provinces.

Sindh remains frozen. Its education ministry and the Sindh Textbook Board have long set the highest standards of laziness, depravity and stupidity. An earlier analysis of STB’s science books was published in this newspaper two years ago. It has had zero effect; matters are just as grim there today as then.

Those who rule Sindh continue to stifle education. Sindh could have outraced Punjab by taking advantage of the 18th Constitutional Amendment which frees the provinces from the federal diktat. Instead, secretaries of education in Sindh who worked to improve things were defeated and shunted out. Sindh’s misfortune has been the ideology-free money-grabbing PPP which oversees a system based upon patronage and unlimited corruption.

With KP’s cleaner administration one expected better. The earlier ANP government had considerably softened textbooks in KP. But after Imran Khan’s PTI entered into an alliance with the Jamaat-i-Islami (and now possibly with arch-conservative Maulana Samiul Haq), there was drastic backpedaling....

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 15, 2017 at 6:23pm

-

Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) ranks first among eight Pakistani territories with respect to the provision of quality education, according to the Pakistan District Education Rankings 2017 released by Alif Ailaan, an education campaign, on Thursday.

AJK is followed by Islamabad Capital Territory, Punjab and Gilgit-Baltistan. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) ranks fifth on the list. Sindh and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) have fallen to seventh and eighth positions, respectively, as Balochistan jumped two places from last year's rankings to sixth position.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1376593

According to Alif Ailaan, the education index covers retention from primary to middle and middle to high schools, learning among students and gender parity.

"The 2017 rankings show that while certain parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab have made marked improvements in school infrastructure, the pace of progress in Sindh, Balochistan and Fata remains a concern," the report noted.

It also highlighted that "authorities continue to prioritise school infrastructure at the expense of what happens in classrooms."

Soon after the report was released, Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) Chairman Imran Khan tweeted: "Alif Ailaan has put out these amazing figures on District Education Rankings for 2017. Nine of the 10 top districts are from KP; only 1 from Punjab. In same survey for 2016, nine of top 10 were from Punjab; none from KP. A great achievement by PTI govt in KP in critical field of education."

However, seemingly validating the concern raised by Alif Ailaan, Khan chose to highlight the "primary school infrastructure scores" instead of overall education scores. Under the latter measure, only one KP district, Haripur — which is placed at the top of the rankings — is among the top 10. Five AJK districts and four districts from Punjab make up the remaining list.

According to the rankings, Faisalabad is Punjab's best performing district for the year while Karachi West (ranked 14 in the country) is the top-ranked district in Sindh.

In Balochistan, the provincial capital is top-ranked (ranked 45 in Pakistan) while Awaran is the worst performing district for the year. Awaran is also ranked at 137 in the country, two places above Sindh's lowest-ranked district for the metric, Sujawal.

"Strides to improve primary school infrastructure in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province are demonstrated by the fact that their lowest ranked district is Shangla at 62," the report highlighted.

Punjab and KP also dominate the "middle school infrastructure scores", with two top districts for the metric being Malakand and Swabi, while the next eight are from Punjab.

The rankings also reveal that a lot of school-going children are out of schools because of a lack of schools above the primary level, confirming previous concerns by the campaign on education.

"For every four primary schools in Pakistan, there is only one school above primary level. This means that most children who pass Class 5 do not have schools to continue their education. The large out of school population of the country is a direct product of this failure."

The report said that the disparities between districts within a province reflect the "failure of programming at the provincial level."

In a stark reminder about the gender gap prevalent in the country, the report revealed "there are more than 55 districts in Pakistan where the total number of girls enrolled in high schools is less than one thousand."

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 4, 2018 at 10:44am

-

Pakistan’s lessons in school reform

What the world’s sixth most populous state can teach other developing countries

https://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21734000-what-worlds-sixth-m...Pakistan has long been home to a flourishing market of low-cost private schools, as parents have given up on a dysfunctional state sector and opted instead to pay for a better alternative. In the province of Punjab alone the number of these schools has risen from 32,000 in 1990 to 60,000 by 2016. (England has just 24,000 schools, albeit much bigger ones.)

More recently, Pakistani policymakers have begun to use these private schools to provide state education. Today Pakistan has one of the largest school-voucher schemes in the world. It has outsourced the running of more government-funded schools than any other developing country. By the end of this year Punjab aims to have placed 10,000 public schools—about the number in all of California—in the hands of entrepreneurs or charities. Although other provinces cannot match the scope and pace of reforms in Punjab, which is home to 53% of Pakistanis, Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are implementing some similar changes on a smaller scale.

The results are promising—and they hold lessons for reformers in other countries. One is that “public-private partnerships” can improve children’s results while costing the state less than running schools itself. A paper published in August by the World Bank found that a scheme to subsidise local entrepreneurs to open schools in 199 villages increased enrolment of six- to ten-year-olds by 30 percentage points and boosted test scores. Better schools also led parents to encourage their sons to become doctors not security guards, and their daughters to become teachers rather than housewives.

Other new research suggests that policymakers can also take simple steps to fix failures in the market for low-cost private schools. For example, providing better information for parents through standardised report cards, and making it easier for entrepreneurs to obtain loans to expand schools, have both been found to lead to a higher quality of education.

Another, related lesson is that simply spending more public money is not going to transform classrooms in poor countries. The bulk of spending on public education goes on teachers’ salaries, and if they cannot teach, the money is wasted. A revealing recent study looked at what happened between 2003 and 2007, when Punjab hired teachers on temporary contracts at 35% less pay. It found that the lower wages had no discernible impact on how well teachers taught.

Such results reflect what happens when teachers are hired corruptly, rather than for their teaching skills. Yet the final and most important lesson from Pakistan is that politicians can break the link between political patronage and the classroom. Under Shahbaz Sharif, Punjab’s chief minister, the province has hired new teachers on merit, not an official’s say-so. It uses data on enrolment and test scores to hold local officials to account at regular high-stakes meetings.

Shifting from “the politics of patronage” to “the politics of performance”, in the words of Sir Michael Barber, a former adviser to the British government who now works with the Punjabis, would transform public services in poor countries. Pakistan’s reforms have a long way to go. But they already have many lessons to teach the world.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 4, 2018 at 6:58pm

-

Pakistan is home to the most frenetic education reforms in the world

Reformers are trying to make up for generations of neglect

https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21733978-reformers-are-tryi...EVERY three months, Shahbaz Sharif, the chief minister of Punjab, gathers education officials around a large rectangular table. The biggest of Pakistan’s four provinces, larger in terms of population (110m) than all but 11 countries, Punjab is reforming its schools at a pace rarely seen anywhere in the world. In April 2016, as part of its latest scheme, private providers took over the running of 1,000 of the government’s primary schools. Today the number is 4,300. By the end of this year, Mr Sharif has decreed, it will be 10,000. The quarterly “stocktakes” are his chance to hear what progress is being made towards this and other targets—and whether the radical overhaul is having any effect.

For officials it can be a tough ride. Leaders of struggling districts are called to Lahore for what Allah Bakhsh Malik, Punjab’s education secretary, calls a “pep talk”. Asked what that entails, he responds: “Four words: F-I-R-E. It is survival of the fittest.” About 30% of district heads have been sacked for poor results in the past nine months, says Mr Malik. “We are working at Punjabi speed.”

Pakistani education has long been atrocious. A government-run school on the outskirts of Karachi, in the province of Sindh, is perhaps the bleakest your correspondent has ever seen. A little more than a dozen children aged six or seven sit behind desks in a cobwebbed classroom. Not one is wearing a uniform; most have no schoolbags; some have no shoes. There is not a teacher in sight.

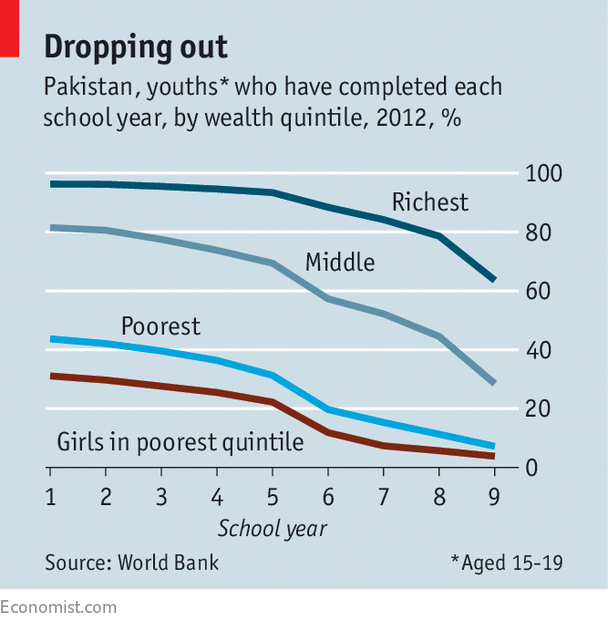

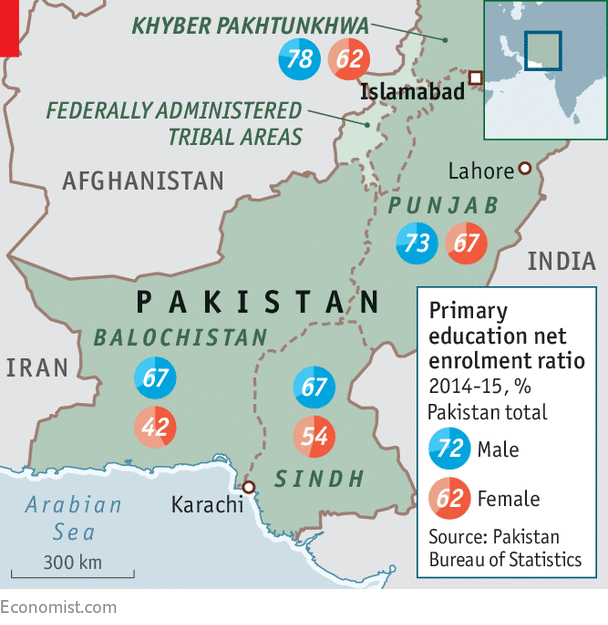

Most Pakistani children who start school drop out by the age of nine; just 3% of those starting public school graduate from 12th grade, the final year. Girls from poor families are least likely to attend (see chart); Pakistan’s gap between girls’ and boys’ enrolment is, after Afghanistan’s, the widest in South Asia. Those in school learn little. Only about half of Pakistanis who complete five years of primary school are literate. In rural Pakistan just over two-fifths of third-grade students, typically aged 8 or 9, have enough grasp of arithmetic to subtract 25 from 54. Unsurprisingly, many parents have turned away from the system. There are roughly 68,000 private schools in Pakistan (about one-third of all schools), up from 49,000 in 2007. Private money currently pays for more of Pakistan’s education than the government does.

It is in part the spread of private options that has spurred politicians like Mr Sharif into action. The outsourcing of schools to entrepreneurs and charities is on the rise across the country. It is too early to judge the results of this massive shake up, but it seems better than the lamentable status quo. If this wholesale reform makes real inroads into the problems of enrolment, quality and discrimination against girls that bedevil Pakistan, it may prove a template for other countries similarly afflicted.

There are many reasons for the old system’s failure. From 2007-15 there were 867 attacks by Islamist terrorists on educational institutions, according to the Global Terrorism Database run by the University of Maryland. When it controlled the Swat river valley in the north of the country, the Pakistani Taliban closed hundreds of girls’ schools. When the army retook the area it occupied dozens of them itself.

Poverty also holds children back. Faced with a choice between having a child help in the fields or learn nothing at school, many parents rationally pick the former. The difference in enrolment between children of the richest and poorest fifth of households is greater in Pakistan than in all but two of the 96 developing countries recently analysed by the World Bank.

Yet poverty is not the decisive factor. Teaching is. Research by Jishnu Das of the World Bank and colleagues has found that the school a child in rural Pakistan attends is many times more important in explaining test scores than either the parents’ income or their level of literacy. In a paper published in 2016, Mr Das and Natalie Bau of the University of Toronto studied the performance of teachers in Punjab between 2003 and 2007 who were hired on temporary contracts. It turned out that their pupils did no worse than those taught by regular ones, despite the temporary teachers often being comparatively inexperienced and paid 35% less.

Teachers’ salaries account for at least 87% of the education budget in Pakistan’s provinces. A lot of that money is completely wasted. Pakistan’s political parties hand out teaching jobs as a way of recruiting election workers and rewarding allies. Some teachers pay for the job: 500,000 rupees ($4,500) was once the going rate in Sindh. At the peak of the problem a few years ago, an estimated 40% of teachers in the province were “ghosts”, pocketing a salary and not turning up.

“Pupils’ learning outcomes are not politically important in Pakistan,” says the leader of a large education organisation. Graft is not the only problem. Politicians have treated schools with a mix of neglect and capriciousness. Private schools have been nationalised (1972) and denationalised (1979); Islam has been inserted and removed as the main part of the curriculum. The language of instruction has varied, too; Punjab changed from Urdu to English, only to revert to Urdu. Sindh, where teachers who are often Sindhi speakers may struggle to teach Urdu, announced in 2011 that Mandarin would be compulsory in secondary schools.

Getting schooled

It is against this background that organisations like The Citizens Foundation (TCF) have developed. The charity runs perhaps the largest network of independently run schools in the world, educating 204,000 pupils at not-for-profit schools. It is also Pakistan’s largest single employer of women outside the public sector; in an effort to make girls feel safer in class, all of TCF’s 12,000 teachers are female. At its Shirin Sultan Dossa branch near a slum on the outskirts of Karachi, one girl is more than holding her own. At break-time on the makeshift cricket pitch she is knocking boys’ spin-bowling out of the playground.

In 2016 TCF opened its first “college” for 17- and 18-year-olds at this campus in an attempt to keep smart poor pupils in school longer. Every day it buses 400 college pupils in from around the city. It builds schools using a standard template, typically raising about $250,000 for each of them from donors; it recruits and trains teachers; and it writes its own curriculums.

Since 2015 TCF has taken over the running of more than 250 government schools in Punjab, Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It gets a subsidy of around 715 rupees per month per child, which it tops up with donations. So far it has increased average enrolment at schools from 47 to 101 pupils, and test results have improved.

The outsourcing of state schools to TCF is just one part of the Sindh government’s recent reforms. “Three years ago we hit rock bottom,” says a senior bureaucrat, noting that 14,000 teaching jobs had been doled out in one year to supporters of the ruling Pakistan Peoples Party. Since then it has used a biometric attendance register to cut 6,000 ghost teachers from the payrolls, and merged 4,000 sparsely attended schools into 1,350. Through the Sindh Education Foundation, an arms-length government body, it is funding “public-private partnerships” covering 2,414 schools and 653,265 pupils. As well as the outsourcing programme, schemes subsidise poor children to attend cheap private schools and pay entrepreneurs to set up new ones in underserved areas.

This policy was evaluated in a paper by Felipe Barrera-Osorio of Harvard University and colleagues published last August. The researchers found that in villages assigned to the scheme, enrolment increased by 30% and test scores improved. Parents raised their aspirations—they started wanting daughters to become teachers, rather than housewives. These results were achieved at a per-pupil cost comparable to that of government schools. “Pakistan’s education challenge is not underspending. It is misspending,” says Nadia Naviwala of the Wilson Centre, a think-tank.

While Sindh has pioneered many policies, Punjab has taken them furthest. The Punjab Education Foundation (PEF), another quasi-independent body, oversees some of the largest school-privatisation and school-voucher programmes in the world. It has a seat with the ministers and administrators at Mr Sharif’s quarterly meetings. The Punjab government no longer opens new schools; all growth is via these privately operated schools. Schools overseen by PEF now teach more than 3m children (an additional 11m or so remain in ordinary government-run schools).

This use of the private sector is coupled with the command-and-control of Mr Sharif, who is backed by Britain’s Department for International Development, which helps pay for support from McKinsey, a consultancy, and Sir Michael Barber, who ran British prime minister Tony Blair’s “Delivery unit”. The latest stocktake claimed an “unprecedented” 10% increase in primary-school enrolment since September 2016, an extra 68,000 teachers selected “on merit”, and a steady increase in the share of correct answers on a biannual test of literacy and numeracy.

Some are concerned about the stress on meeting targets in this “deliverology” model. For one thing, independent assessment of the system’s claimed success is hard. Mr Das argues that there is no evidence from public sources that support Punjab’s claims of improved enrolment since 2010. Nor is the fear provoked by Mr Sharif always conducive to frank self-appraisal: some officials may fudge the numbers. Ms Naviwala points out that two of the worst-performing districts in spring 2015 somehow became the highest performers a few months later. She suggests that similar data-driven reforms in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa may have a better chance of success, since they are less dependent on the whims of a single minister. For their part Punjab and its international backers insist that the data are accurate, and that the other publicly available data are out of date.

No one thinks that everything is fixed. Around the corner from that parlous primary school on the outskirts of Karachi is another, privately run school hand-picked for your correspondent’s visit by civil servants. In maths classes pupils’ workbooks have no entries for the past fortnight. What sums there are show no working; answers were simply copied. The head teacher seems to care most about his new audiovisual room, the screen in which is not for pupils, but for him: a bootleg Panopticon, with six CCTV feeds displayed on a wall-mounted screen. This is an effective way of dealing with ghosts. But as the head explains how great his teachers are, one of them strolls up to a boy in the front of her class and smacks him over the head.

Even if there is bluster aplenty and a long way to go, though, the fact that politicians are burnishing their reputations through public services, rather than patronage alone, is a step forward. And if there is a little Punjabi hype to go with the Punjabi speed, then that may be a price worth paying. For too long Pakistani children have suffered because politicians have treated schools as political tools. They deserve much better.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on February 17, 2018 at 4:14pm

-

#Pakistan #Children #Literature Festival #CFL in #Lahore Makes #Education a Fun Activity

https://www.truthdig.com/articles/pakistani-festival-makes-educatio...In January 2018, Lahore, the seat of government of Pakistan’s largest province, Punjab, played host to the Children’s Literature Festival (CFL), a unique experiment in making education a fun activity. Thousands of children gathered on the scenic lawns of the historic Lahore Fort to hear stories, listen to music and songs, and watch plays and dances.

But this was not an entertainment event alone. It was more like a gigantic, unconventional school, and in many cases the children were their own teachers.

January’s festival was not entirely new for the people of Lahore. In 2011 a similar event—albeit one a bit more serious—was held on the Punjab Public Library grounds. In 2014 Lahore again played host to the CLF.

The CLF has come a long way over the course of its six-year journey. The session in January was the 45th held in Pakistan since 2011. So far, the CLF has reached a million children. It is now a registered company with six directors and a secretariat at the Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi (“Center for Education and Consciousness,” or ITA), the parent organization under which CLF was originally conceived. ITA provides secretarial and technical support to CLF so that the latter remains a lean organization with minimal overheads and maximum outreach. The CLF has gone all over Pakistan, from big cities to small towns. Over the years it has evolved and has crept into neighboring cities in India and Nepal as well.

Children participate in a puppet-making workshop at the Children’s Literature Festival. (Zubeida Mustafa)

How did it all begin? The United Nations recognizes education as a child’s right. Yet UNESCO estimates that 263 million children are out of school worldwide. Since education is linked closely to development and progress, the U.N. attached much importance to education when creating its Millennium Development Goals (2000-2015) and Sustainable Development Goals (2015-2030). The first blueprint sought universal primary education by 2015. The second has set the goal of quality education up to secondary level for all children by 2030. Pakistan never achieved the first. For that country, the second also appears to be beyond reach.

At present, almost 23 million children are believed to be out of school in Pakistan. It is not just lack of access that is a problem—the poor quality of education nullifies whatever small advantage is achieved in terms of enrollment. Both issues need to be addressed if the universalization of education is to be meaningful.

Of course, not all Pakistani children enrolled in school learn the basic literacy and numeracy skills needed to promote lifelong learning. Some of the statistics released from time to time are dismal in the extreme.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 12, 2018 at 2:10pm

-

Out-of-school children to get non-formal education

https://dailytimes.com.pk/213850/out-of-school-children-to-get-non-...

National Commission for Human Development (NCHD) will put millions of out of school children in non-formal schools to help them catch up with studies through accelerated learning in short span of three years, said the commission’s deputy director.

In this regard, NCHD has inked a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with ARC for a period of three-years under Education Above All Foundation’s programme Educate-A-Child (EAC). NCHD Director General Samina Waqar and ARC Deputy Chief of Party Daud Saqlain signed the agreement.

Over the next three years, ARC will work to provide quality primary education to 1,050,000 marginalised Out-Of-School-Children (OOSC) in Pakistan. This project is being supported by Qatar Foundation. The purpose of this memorandum of understanding is to outline the respective roles, responsibilities and liabilities of ARC (American Refugee Committee) and NCHD in the implementation of “provision of access to OOSC ” in 12 districts of Punjab and Balochistan.

Earlier chairing a meeting, Samina Waqar said NCHD was looking for technical partnerships for development of curriculum for non-formal education. The second meeting of Technical Committee for Development of Teaching- Learning Resources for Accelerated Learning Programme (ALP) was held to finalise a list of potential writers for developing the accelerated learning courses for children of who did not get an opportunity to get enrolled in school.

Technical partnership for challenging task of development of Teaching Learning Resources for Non-Formal Education is prime concern of NCHD, this was observed by the experts in the second meeting of Technical Committee for development of Teaching- Learning Resources for Accelerated Learning Programme (ALP), at NCHD head quarter, the other day.

Experts of Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Allama Iqbal Open University (AIOU) and NCHD were trying to strategise a detailed course of action for development and review of draft ALP Teaching Learning Resource and to finalise a list of potential writers for developing the accelerated learning courses in light of their expertise.

The courses are being designed with an idea to impart, character building and social learning along with literacy skills for out of school children of nine years and above, who have missed school and did not get an opportunity to enrolled in school.

The NCHD DG said there were still 22.8 million children of 5-16 years of age who were out of school. Among these children there are 6.4 million of 10 to16 years, those who cannot be enrolled in government primary schools due to their age factor. She said NCHD was devising a three-year plan to enrol all these children in non-formal schools.

This Teaching Learning Resource which will be prepared by the joint efforts of National Training Institute of NCHD, AQAL-JICA and AIOU would be helpful to impart non-formal education to these 6.4 million children enabling them to catch up with studies in a limited span of time, as they would be able to pass primary exam, Samina said.

NCHD always welcomed the idea of joint ventures in gearing up with other stakeholders for eradicating illiteracy in the country, she added.

NCHD had remained very successful in these joint ventures and served the purpose effectively and efficiently as well, she said. “ARC and NCHD cooperation and collaboration in the field of education under Educate-A-Child is another milestone for us, I hope that we will succeed in this venture as well,” she further added.

JICA country representative Chiho Ohashi and Daud Saqlain appreciated the expertise and professional ability of NCHD experts.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 28, 2018 at 10:06am

-

Pakistan’s literacy rate stands at 58pc

https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/309542-pakistan-s-literacy-rate-st...

Pakistan’s overall literacy rate remains static at 58 percent with literacy rate of males 70 percent and 48 percent of females, as due to the Population and Housing Census, the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement was not carried out for 2017-18.

Therefore, the Pakistan Economic Survey says that the figures for 2015-2016 should be considered for the current year as well.

According to the Pakistan Economic Survey, 2017-2018, the literacy rate for entire Pakistan, includes ten years old and above is 58 percent. The national net enrollment for primary level for overall Pakistanstood at 54 percent while Punjab leading the rest with 59 percent, followed by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa with 53, Sindh by 48 percent and Balochistan 33 percent.

Similarly, the gross enrollment rate for Pakistan is 87 percent and again Punjab in the lead with 93 percent, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 88 percent, Sindh 78 percent and Balochistan 60 percent. The gross enrollment for males is 94 percent and 78 percent for females.

Public expenditure on education as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) is estimated to be 2.2 percent in financial year 2017 as compared to 2.3 percent of GDP in financial year 2016.

Likewise, the Economic Survey says that the education-related expenditure increased by 5.4 percent to Rs699.2 billion in financial year 2017 from Rs663.4 billion financial year 2016. It noted that the provincial governments also are spending sizeable amount of their annual development plans on education.

A total of 5.1 thousand higher secondary schools/inter colleges with 120.3 thousand teachers were functional in 2016-17. A decrease of 6.1 percent in higher secondary enrolment has been observed as it dropped to 1,594.9 thousand in 2016-17 against 1,698.0 thousand in 2015-16. It is estimated to increase by 9.8 percent i.e. from 1,594.9 thousand to 1750.6 thousand in 2017-18.

The overall education condition is based on key performance indicators such as enrolment rates, number of institutes and teachers which have experienced minor improvement. The total number of enrolments at national level during 2016-17 stood at 48.062 million as compared to 46.223 million during 2015-16. This shows a growth of 3.97 percent and it is estimated to further rise to 50.426 million during 2017-18.

The total number of institutes stood at 260.8 thousands during 2016-17 as compared to 252.8 thousands during last year and the number of institutes are estimated to increase to 267.7 thousands during 2017-18.

The total number of teachers during 2016-17 were 1.726 million compared to 1.630 million during last year showing an increase of 5.9 percent. This number of teachers is estimated to rise further to 1.808 million during the year 2017-18.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 29, 2018 at 7:11pm

-

#Pakistan ‘Street #Schools’ Open to Poor Kids, Parents. "The program is called Street to School. Organizers launched it in the Pakistani city of #Karachi in 2014" #education

https://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/pakistan-street-schools-open-...

A different kind of school in Pakistan is giving poor children, and sometimes their mothers too, a new chance to get an education.

The program is called Street to School. Organizers launched it in the Pakistani city of Karachi in 2014. The idea was to create a school for children who played on the streets every day while their parents worked. Some parents chose not to send their children to school, while others did not have enough money to do so.

The founder of Street to School is Mohammad Hassan. He says children who spend all day on the streets are at risk for a number of reasons. They are in danger of catching dangerous diseases and can also be caught up in crime and drug use. Others are forced to work.

Street to School is a way to keep these children off the streets, while providing them with a basic education and useful life skills.

Hassan says the preschool education program centers on reading, writing and mathematics. Students are also taught English as well as the local language, Urdu. In addition, Street to School includes sports activities and provides students with information on how to stay healthy and take care of themselves.

Hassan says Street to School has been successful in getting children off the streets and on a new path toward an education in traditional schools. But running the school also taught him about another great need in the community.

“We started this project for kids. But we found out very quickly the kids would bring their homework diaries without parents’ signatures. That meant kids were not getting the needed help at home to do their homework. So, we decided to create a special course for these parents so that they can have basic literacy to help their kids.”

Uzma is a wife and mother who decided for herself she wanted to join Street to School.

“I talked to my husband. He gave me his permission, which is a huge deal. So many women don't get this opportunity. This is why I am here today. I come here, and I study with God's blessing. I have learned enough now that I don't feel dependent on anyone.”

--------

Karachi has other educational programs for street children. One of them is called The Street School. Two teenagers, Hasan and Shireen Zafar, started the program. It aims to bring education to the streets for groups of needy children around the city.

The founders told Pakistan’s Dunya News television they decided to launch the school after a girl came up to them and asked an unusual question. Instead of asking for money, the girl asked, “Will you teach me?”

The program started out with just two students, but grew to more than 200. The Zafars told Dunya News one of their main goals is to prevent people from abusing children as laborers.

The Street School also has begun to teach some adults, most of whom are parents of children involved in the program.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 20, 2018 at 4:28pm

-

If you score more than 33% on Hans Rosling's basic facts quiz about the state of health and wealth in the world today, you know more about the world than a chimp

Read more at: https://inews.co.uk/news/long-reads/hans-rosling-factfulness-statis...

Excerpt of Factfulness by Hans RoslingPage 201

This is risky but I am going to argue it anyway. I strongly believe that liberal democracy is the best way to run a country. People like me, who believe this, are often tempted to argue that democracy leads to, or its even a requirement for, other good things, like peace, social progress, health improvement, and economic growth. But here's the thing, and it is hard to accept: the evidence does not support this stance.Most countries that make great economic and social progress are not democracies. South Korea moved from Level 1 to Level 3 (Rosling divides countries into 4 levels in terms of development, not the usual two categories of developed and developing) faster than any other country had ever done (without finding oil), al the time as a military dictatorship. Of the ten countries with the fastest economic growth, nine of them score low on democracy.Anyone who claims that democracy is a necessity for economic growth and health improvements will risk getting contradicted by reality. It's better to argue for democracy as a goal in itself instead of as a superior means to other goals we like.

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Pakistani Student Enrollment in US Universities Hits All Time High

Pakistani student enrollment in America's institutions of higher learning rose 16% last year, outpacing the record 12% growth in the number of international students hosted by the country. This puts Pakistan among eight sources in the top 20 countries with the largest increases in US enrollment. India saw the biggest increase at 35%, followed by Ghana 32%, Bangladesh and…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on April 1, 2024 at 5:00pm

Agriculture, Caste, Religion and Happiness in South Asia

Pakistan's agriculture sector GDP grew at a rate of 5.2% in the October-December 2023 quarter, according to the government figures. This is a rare bright spot in the overall national economy that showed just 1% growth during the quarter. Strong performance of the farm sector gives the much needed boost for about …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on March 29, 2024 at 8:00pm

© 2024 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network