PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

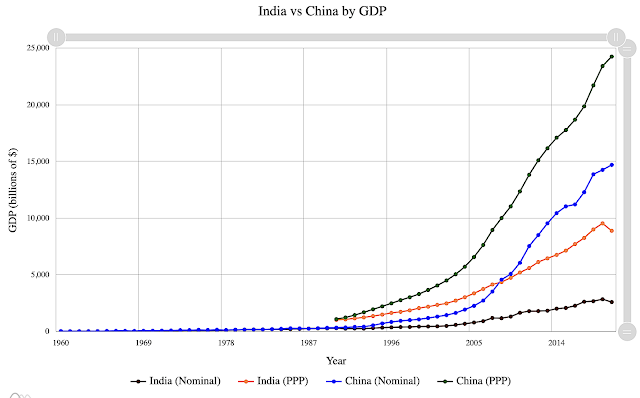

Why Does India Lag So Far Behind China?

Indian mainstream media headlines suggest that Pakistan's current troubles are becoming a cause for celebration and smugness across the border. Hindu Nationalists, in particular, are singing the praises of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and some Pakistani analysts have joined this chorus. This display of triumphalism and effusive praise of India beg the following questions: Why are Indians so obsessed with Pakistan? Why do Indians choose to compare themselves with much smaller Pakistan rather than to their peer China? Why does India lag so far behind China when the two countries are equal in terms of population and number of consumers, the main draw for investors worldwide? Obviously, comparison with China does not reflect well on Hindu Nationalists because it deflates their bubble.

|

| Comparing China and India GDPs. Source: Statistics Times |

|

| Top Patent Filing Nations in 2021. Source: WIPO.Int |

|

| India's Weighting in MSCI EM Index Smaller Than Taiwan's. Source: N... |

The US Commerce Department is actively promoting India Inc to become an alternative to China in the West's global supply chain. US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo recently told Jim Cramer on CNBC’s “Mad Money” that she will visit India in March with a handful of U.S. CEOs to discuss an alliance between the two nations on manufacturing semiconductor chips. “It’s a large population. (A) lot of workers, skilled workers, English speakers, a democratic country, rule of law,” she said.

India's unsettled land border with China will most likely continue to be a source of growing tension that could easily escalate into a broader, more intense war, as New Delhi is seen by Beijing as aligning itself with Washington.

In a recent Op Ed in Global Times, considered a mouthpiece of the Beijing government, Professor Guo Bingyun has warned New Delhi that India "will be the biggest victim" of the US proxy war against China. Below is a quote from it:

"Inducing some countries to become US' proxies has been Washington's tactic to maintain its world hegemony since the end of WWII. It does not care about the gains and losses of these proxies. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is a proxy war instigated by the US. The US ignores Ukraine's ultimate fate, but by doing so, the US can realize the expansion of NATO, further control the EU, erode the strategic advantages of Western European countries in climate politics and safeguard the interests of US energy groups. It is killing four birds with one stone......If another armed conflict between China and India over the border issue breaks out, the US and its allies will be the biggest beneficiaries, while India will be the biggest victim. Since the Cold War, proxies have always been the biggest victims in the end".

Related Links:

Do Indian Aircraft Carriers Pose a Threat to Pakistan's Security?

Can Washington Trust Modi as a Key Ally Against China?

Ukraine Resists Russia Alone: A Tale of West's Broken Promises

Ukraine's Lesson For Pakistan: Never Give Up Nuclear Weapons

AUKUS: An Anglo Alliance Against China?

Russia Sanction: India Profiting From Selling Russian Oil

Indian Diplomat on Pakistan's "Resilience", "Strategic CPEC"

Vast Majority of Indians Believe Nuclear War Against Pakistan is "W...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 6, 2023 at 10:04am

-

Will India Surpass China to Become the Next Superpower?

Four inconvenient truths make this scenario unlikely.https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/06/24/india-china-biden-modi-summit-...

by Prof Graham Allison, Harvard's Kennedy School of Government

when assessing a nation’s power, what matters more than the number of its citizens is the quality of its workforce. China’s workforce is more productive than India’s. The international community has rightly celebrated China’s “anti-poverty miracle” that has essentially eliminated abject poverty. In contrast, India continues to have high levels of poverty and malnutrition. In 1980, 90 percent of China’s 1 billion citizens had incomes below the World Bank’s threshold for abject poverty. Today, that number is approximately zero. Yet more than 10 percent of India’s population of 1.4 billion continue to live below the World Bank extreme poverty line of $2.15 per day. Meanwhile, 16.3 percent of India’s population was undernourished in 2019-21, compared with less than 2.5 percent of China’s population, according to the most recent United Nations State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report. India also has one of the worst rates of child malnutrition in the world.Fortunately, the future does not always resemble the past. But as a sign in the Pentagon warns: Hope is not a plan. While doing whatever it can to help Modi’s India realize a better future, Washington should also reflect on the assessment of Asia’s most insightful strategist. The founding father and long-time leader of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, had great respect for Indians. Lee worked with successive Indian prime ministers, including Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi, hoping to help them make India strong enough to be a serious check on China (and thus provide the space required for his small city-state to survive and thrive).

But as Lee explained in a series of interviews published in 2014, the year before his death, he reluctantly concluded that this was not likely to happen. In his analysis, the combination of India’s deep-rooted caste system that was an enemy of meritocracy, its massive bureaucracy, and its elites’ unwillingness to address the competing claims of its multiple ethnic and religious groups led him to conclude that it would never be more than “the country of the future”—with that future never arriving. Thus, when I asked him a decade ago specifically whether India could become the next China, he answered directly: “Do not talk about India and China in the same breath.”

Since Lee offered this judgment, India has embarked on an ambitious infrastructure and development agenda under a new leader and demonstrated that it can achieve considerable economic growth. Yet while we can remain hopeful that this time could be different, I, for one, suspect Lee wouldn’t bet on it.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 6, 2023 at 10:36am

-

Remembering Lee Kuan Yew and What He Had to Say About India

https://www.thequint.com/news/world/what-lee-kuan-yew-had-to-say-ab...

I belong to that generation of Asian nationalists who looked up to India’s freedom struggle and its leaders Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru.

The words of Singapore’s ‘founding father’ Lee Kuan Yew who transformed Singapore from just another nondescript colonial outpost and sea port to a global financial power centre. The Economist’s Where-to-be-born Index in 2013, ranked Singapore 6 out of 111 countries.

Until his death at the age of 91, Lee remained a highly-revered figure in Singapore. He was the island city-state’s first and longest-serving Prime Minister having served for over three decades till 1990.

Lee looked up to India’s Nehru, but it was China’s Deng Xiaoping whom he seemed to have inspired.

Lee’s views on India ranged from admiration to friendly nudges to strong disdain.

“How Will Lee Yuan Kew Govern India?”

In 2013, an IAS officer asked Lee if he could do to India what he did to Singapore.

Lee responded, “No single person can change India”, putting it down to the complexity created by its diverse culture and nature. India, Lee continued, “is diverse and therefore it has to work at its own speed.”

“As I grew up there are many different Indias and that stays true today. If you make the whole of India like a Bombay, then you get a different India,” Lee suggested pointing towards Mumbai’s ability to assimilate from across different backgrounds.

Lee even had a mantra for Indian politicians on good governance, “Integrity - absence of corruption, meritocracy - best people for the best job and a fair level playing field for everybody.”

“Unfulfilled Greatness”

Lee spoke of India’s potential and its long overdue “tryst with destiny”. In the second volume of his memoirs, published in 2000, he wrote,

India is a nation of unfulfilled greatness. Its potential has lain fallow, under used.

“Not a Real Country”

When Nehru was in charge, I thought India showed promise of becoming a thriving society and a great power,” but it has not “because of its stifling bureaucracy” and its “rigid caste system.” Being deliberately provocative, Lee says: “India is not a real country. Instead it is thirty-two separate nations that happen to be arrayed along the British rail line.

- In a series of interviews to Harvard Kennedy School’s Graham Allison and former US Ambassador to India, Robert D. Blackwill, published in 2013.

“No Longer a Wounded Civilisation”

India is an intrinsic part of this unfolding new world order. India can no longer be dismissed as a “wounded civilisation”, in the hurtful phrase of a westernised non resident Indian author (V.S. Naipal). Instead, the western media, market analysts, and the International Financial Institutions now show-case India as a success story and the next big opportunity.

- At the 37th Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Lecture on 21st Nov 2005 in New Delhi.

“Not Going to be Everybody’s Lackey”

There will be the U.S., there will be China, the Indians are going to be themselves, they’re not going to be everybody’s lackey. They may not be as big as China in GDP.

- In an interview to veteran journalist Charlie Rose.

On India and China

If India were as well-organized as China, it will go at a different speed, but it’s going at the speed it is because it is India. It’s not one nation. It’s many nations. It has 320 different languages and 32 official languages.

https://youtu.be/5vELNwtQO1E

Jul 25, 2013

"If someone were to give you India today, can you do to India what you did to Singapore over the last three decades?" Former Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew gives his take.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 17, 2023 at 4:34pm

-

India needs to grow at 7.6% a year for 25 yrs to be a developed nation -central bank bulletin

https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-needs-grow-76-year-25-yrs...

MUMBAI, July 17 (Reuters) - India will need to grow at a rate of 7.6% annually for the next 25 years to become a developed nation, according to a research paper published by the central bank in its monthly bulletin on Monday.

India's per capita income is currently estimated at $2,500, while it must be more than $21,664 by 2047, as per World Bank standards, to be classified as a high-income country.

"To achieve this target, the required real GDP compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) for India works out to be 7.6% during 2023-24 to 2047-48," according to the study by the Reserve Bank of India's economic research department.

In nominal terms, which includes the impact of inflation, the economy would need to clock a CAGR of 10.6%, said the study, which does not represent the RBI's official view.

"It may, however, be mentioned that the best (nominal growth) India achieved over a period of consecutive 25 years in the past is a CAGR of 8.1% during 1993-94 to 2017-18."

To reach that level of sustained growth, India requires investment in physical capital and reforms across sectors covering education, infrastructure, healthcare and technology, the study said.

The country's industrial and services sector would need to grow at over 13% annually for these 25 years for India to achieve developed economy status, it said.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 19, 2023 at 5:24pm

-

India will soon become third largest economy. Does it matter?Given the depreciating USD, India’s $5tn GDP goal of 2019-20 equals $5.74tn in 2022-23, and at further 3 per cent depreciation, it would need to be $6.65tn in 2027-28. Subhash Chandra Garg

Read more at: https://www.deccanherald.com/opinion/india-will-soon-become-third-l...

"When I first visited the US as a Prime Minister, India was the 10th largest economy in the world. Today, India is the 5th largest, and we will be the third largest soon," Prime Minister Narendra Modi said, with pride, in his address to the US Congress on June 23

Read more at: https://www.deccanherald.com/opinion/india-will-soon-become-third-l...

India, with GDP of $1.86 trillion, was the ninth largest economy in 2013-14, with Brazil ($2.21 trillion), China ($9.57 trillion), France ($2.81 trillion), Germany ($3.7 trillion), the United Kingdom ($2.79 trillion), Italy ($2.14 trillion), Japan ($5.21 trillion), and the United States ($17.55 trillion) ahead.

It was quite a fortuitous coincidence that the GDP of next four countries — Brazil, Italy, France, and the UK in 2013 — was in a $2-3 trillion band, with India quite close behind. Moreover, except Brazil, all the three European countries had attained very high per capita incomes of $42,603 (France), $43,449 (the UK), and $35,560 (Italy) respectively. Brazil’s lower per capita income of $12,259 was also nearly 10 times India’s per capita income of $1,438.

All high-income countries get into low GDP growth orbit thanks to having attained economic prosperity and falling population, whereas developing countries record higher GDP growth. Unsurprisingly, India, a poor developing country, despite not so impressive growth of about 7 per cent, in current dollars during 2013-2022, moved past these four countries to become the fifth largest. Germany and Japan are also high per capita income countries with declining population.

Germany’s per capita income is $48,438 in 2022, whereas India’s is $2,389. Japan’s case is bizarre. Japan’s GDP was $5.76 trillion in 2010 and only $4.32 trillion in 2022. The IMF projects Germany and Japan’s GDP to be $4.95 trillion and $5.08 trillion respectively in 2027. The IMF projects India’s growth, somewhat optimistically, at 8.72 per cent until 2027-28. If it gets realised, India will move past Germany and Japan that year.

Read more at: https://www.deccanherald.com/opinion/india-will-soon-become-third-l...

Excluding small island economies, India’s per capita income of $1,438 in 2013-14 has increased to $2,389 in 2022-23, at a compounded annual growth rate of 5.8 per cent. India’s rank, in terms of per capita income, was the 147th (out of 189) in 2013-14..we have moved to the 141st rank. Since 2014, India has moved ahead of Nicaragua, Uzbekistan, Mauritania, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, and Lao PDR. On the other hand, Bangladesh — India’s ‘poor’ neighbour — has overtaken us. Per capita income of Brazil, Italy, France, and the UK, whose GDP India has overtaken, and Germany and Japan, which we will cross, remain far higher for us to even think of achieving. The conclusion is clear. India will prosper and develop when the per capita income of average Indian will grow to reach higher middle-income levels, if not the high-income level — and not when its GDP becomes the third largest.

(Subhash Chandra Garg is former Finance & Economic Affairs Secretary, and author of ‘The Ten Trillion Dream’ and ‘Explanation and Commentary on Budget 2023-24’.)

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 24, 2023 at 6:35pm

-

Riaz Haq has left a new comment on your post "Declining Enrollment of Indian Muslims in Colleges and Universities ":

One metric of note is gross enrollment ratio (GER), which measures total enrollment in education as a percentage of the eligible school-aged population. India’s GER of 27.1 percent in 2019–20 seems poised to fall below the Ministry of Education’s target of achieving 32 percent by 2022.

https://www.nafsa.org/ie-magazine/2022/4/12/indias-higher-education....

India’s higher education landscape is a mix of progress and challenges. Its scope is vast: 1,043 universities, 42,343 colleges, and 11,779 stand-alone institutions make it one of the largest higher education sectors in the world, according to the latest (2019–20) All India Survey of Higher Education Report (AISHE 2019–20).

The number of institutions has expanded by more than 400 percent since 2001, with much of the growth taking place in the private education sector, according to a major 2019 report from the Brookings Institution, Reviving Higher Education in India. This growth continued through 2019–20, according to the 2019–20 AISHE report.

Capacity is growing rapidly to serve India’s large youth population and burgeoning college-aged cohort. One metric of note is gross enrollment ratio (GER), which measures total enrollment in education as a percentage of the eligible school-aged population. India’s GER of 27.1 percent in 2019–20 seems poised to fall below the Ministry of Education’s target of achieving 32 percent by 2022. It is also significantly behind China’s 51 percent and much of Europe and North America, where 80 percent or more of young people enroll in higher education, according to Philip Altbach, a research professor at Boston College and founding director of the Center for International Higher Education.

The number of institutions has expanded by more than 400 percent since 2001. ...Capacity is growing rapidly to serve India’s large youth population and burgeoning college-aged cohort.

India has produced many noteworthy higher education institutions, including those specializing in sciences and business, though none of them take the top spots in global rankings. Its highest-ranked institution, the Indian Institute of Science, was in the 301–350 range among institutions worldwide in 2022, according to the Times Higher Education 2022 World University Rankings. China, by contrast, has 16 institutions in the top 350, including six ranked in the top 100 and two in the top 20. However, much is different about India—its central government is less efficient and empowered, there’s enormous variation between India’s 36 states and territories, there’s less affluence, and the country has a democratic political system.

Across India, there is an enormous variation in quality institutions between states. For instance, according to the National Institutional Ranking Framework of India 2021, the best colleges in the country are concentrated in 9 of India’s 28 states: Delhi, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and West Bengal. The colleges in these states are all in the ranking’s top 100 institutions, notes Eldho Mathews, deputy advisor at the National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration. In states with fewer resources, offering quality education is more of a challenge.

Other difficulties that hobble the sector include lack of sufficient funding at both the national and state levels; inefficient structure; massive bureaucracy; and corruption. An additional, formidable hurdle is to bridge the gap between graduates and jobs, as many employers have doubts about the quality of Indian graduates’ skills. In a recent survey by Wheelbox, Taggd, and the Confederation of Indian Industry, respondents rated graduates of higher education institutions below a 50 percent employability level, according to the resulting Indian Skills Report.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 18, 2023 at 6:55pm

-

Forget world domination, India won’t catch up with China any time soon

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

Even the most India-positive forecasts expect it to spend half a century to overtake the US economically, to take second place behind China

India’s policymakers should focus instead on opening up their economy and recognising that it can still be a huge driver in the global economy

Last year, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi celebrated 75 years of India’s independence from British rule, he called on the nation to “dominate the world”. Earlier this week, once again at the Red Fort, he evoked “Amrit Kaal” – a crucial era when the gates of opportunity open.

His “reform, perform, transform” mantra involves dreaming big. He was possibly dreaming of those halcyon days up to 1870 when India and China counted as the world’s two largest and most powerful economies.

But a dream does not make a plan. And in the nine years since Modi came to power, his plans to propel India to the top table of the world’s most powerful economies remain largely that – plans.

Harvard University’s Graham Allison reminded us in a recent Foreign Policy report that about a decade ago, the late Singapore leader Lee Kwan Yew had said India would never catch up with China and would always remain “the country of the future”. Lee said: “Do not talk about India and China in the same breath” – throwing the gauntlet down to those who see India biting at China’s heels and cheer India on in hopes of hobbling China’s ascent.

To be fair to Modi, his government’s economic performance is respectable after decades of stagnation and disappointment. India’s gross domestic product has grown by about 6 per cent every year on average since 2014, reaching an all-time high of 9.1 per cent last year – impressive in light of the upheavals of the Covid-19 pandemic and recession in many parts of the world.

But a wide range of structural reforms are needed if India is to escape the shackles of its economic past. These include the grip of caste, bureaucratic friction, impenetrable tax rules, still-chronic protection of local business magnates and import tariffs that are among the world’s highest.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 18, 2023 at 6:56pm

-

Forget world domination, India won’t catch up with China any time soon

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, speaking at the Independence Day ceremony at Red Fort in New Delhi on August 15. Photo: Bloomberg

Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, speaking at the Independence Day ceremony at Red Fort in New Delhi on August 15. Photo: Bloomberg

Last year, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi celebrated 75 years of India’s independence from British rule, he called on the nation to “dominate the world”. Earlier this week, once again at the Red Fort, he evoked “Amrit Kaal” – a crucial era when the gates of opportunity open.

His “reform, perform, transform” mantra involves dreaming big. He was possibly dreaming of those halcyon days up to 1870 when India and China counted as the world’s two largest and most powerful economies.

But a dream does not make a plan. And in the nine years since Modi came to power, his plans to propel India to the top table of the world’s most powerful economies remain largely that – plans.

Harvard University’s Graham Allison reminded us in a recent Foreign Policy report that about a decade ago, the late Singapore leader Lee Kwan Yew had said India would never catch up with China and would always remain “the country of the future”. Lee said: “Do not talk about India and China in the same breath” – throwing the gauntlet down to those who see India biting at China’s heels and cheer India on in hopes of hobbling China’s ascent.

To be fair to Modi, his government’s economic performance is respectable after decades of stagnation and disappointment. India’s gross domestic product has grown by about 6 per cent every year on average since 2014, reaching an all-time high of 9.1 per cent last year – impressive in light of the upheavals of the Covid-19 pandemic and recession in many parts of the world.

But a wide range of structural reforms are needed if India is to escape the shackles of its economic past. These include the grip of caste, bureaucratic friction, impenetrable tax rules, still-chronic protection of local business magnates and import tariffs that are among the world’s highest.

A woman carries water in a slum on Independence Day in Hyderabad, India, on August 15. Modi said India’s economy would be among the top three in the world within five years, as he marked 76 years of independence from British rule. Photo: AP

A woman carries water in a slum on Independence Day in Hyderabad, India, on August 15. Modi said India’s economy would be among the top three in the world within five years, as he marked 76 years of independence from British rule. Photo: AP

Any country rising from such a low base must recognise that it will take many decades to achieve anything the late Lee would regard as parity with China – and that this is nothing to be ashamed of. Goldman Sachs predicted last month that by 2075, China would become the world’s largest economy (US$57 trillion), with India (at US$52.5 trillion) overtaking the US (at US$51.5 trillion).

Columbia University’s Arvind Panagariya has similar projections, calculating recently in Time magazine that if India’s real GDP grew at 8 per cent a year into the 2040s and 5 per cent after that, and if the US continues to grow on average by 2 per cent a year, India would overtake the US in 2073.

These are big “ifs”, even for those brave enough to make forecasts a half-century away. And huge bodies of data point India towards a more humdrum trajectory. According to Allison in Foreign Policy, back in 2000, China and India had economies worth less than US$2 trillion each. It took China five years to pass the mark and India 14 years. Last year, India’s economy was worth US$3.4 trillion – a fraction of China’s US$18.3 trillion.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 18, 2023 at 6:57pm

-

Forget world domination, India won’t catch up with China any time soon

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

It will take many years of stellar economic growth for India to begin matching China in economic importance, and no amount of miraculous thinking or “China plus one” investment is likely to accelerate that.

Also, many other important economic indicators remain problematic. India accounted for about 1 per cent of global manufacturing in 2000, compared with 7 per cent for China. By last year, India’s share had grown to 3 per cent against China’s 31 per cent. In 2000, India accounted for just 1 per cent of the world’s exports, and China 2 per cent. By last year, China accounted for 15 per cent of global exports against India’s share of 2 per cent.

India enthusiasts celebrate the youthfulness of India’s population, but ignore the reality that this is a problem rather than an advantage when they are poorly educated or even illiterate. To accommodate them, India must produce an estimated 90 million new jobs before 2030.

Allison reminds us that China produces twice as many STEM-qualified (in science, technology, engineering and mathematics) graduates as India, spends almost three times the percentage of its GDP on research and development, and produces 65 per cent of the world’s artificial intelligence patents (vs India’s 3 per cent).

As Bloomberg noted in April: “India is far behind China in key aspects important for manufacturing that include infrastructure, bureaucracy, attention to detail and even a sense of urgency.”

Supporters of India in search of a “hobble China” narrative have been encouraged by companies such as Apple and its main Taiwanese manufacturer Foxconn, which have made tentative steps to build investments in India, but ignore the challenges they have faced, and the reality that China remains their main manufacturing base.

They have ignored the withdrawals of companies like the Royal Bank of Scotland, Harley-Davidson and Citibank, and the many other companies with plans on hold. They have tended to celebrate the deliberate obstacles to prospective investment in China, even where China is a natural partner and the benefit of collaboration is huge.

Rather than harbouring dreams of dominating the world, India’s policymakers would benefit us all by opening up their economy and recognising that even if India does not surpass China, it can still be a huge driver in the global economy. China and India together account for one third of the world’s population, one third of the global consumer class, and a quarter of all consumer spending in purchasing power parity terms.

The 21st century may not be India’s century, but it is almost certainly Asia’s. Washington needs to come to terms with that, and perhaps New Delhi does too.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 19, 2023 at 4:54pm

-

Ritesh Kumar Singh

@RiteshEconomist

Replacing a supplier from China with one in a friendly country would seem to make a supply chain more resilient to a potential China-US conflict; but it may create a false sense of security, considering that many friendly suppliers still rely on China for key inputs

@Kanthan2030

https://twitter.com/RiteshEconomist/status/1692848048144335220?s=20

------------

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/populist-economic-poli...

Aug 18, 2023

RAGHURAM G. RAJAN

Since the 2008 global financial crisis discredited the old liberal orthodoxy, the door has been open for simplistic policies, in part because most people tend to focus only on a policy’s first-order effects. Unfortunately, everyone will have to learn the hard way why such policies fell out of favor in the first place.

CHICAGO – Even in the best of times, policymakers find it difficult to explain complex issues to the public. But when they have the public’s trust, the ordinary citizen will say, “I know broadly what you are trying to do, so you don’t need to explain every last detail to me.” This was the case in many advanced economies before the global financial crisis, when there was a broad consensus on the direction of economic policy. While the United States placed greater emphasis on deregulation, openness, and expanding trade, the European Union was more concerned with market integration. In general, though, the liberal (in the classical British sense) orthodoxy prevailed.

So pervasive was this consensus that one of my younger colleagues at the International Monetary Fund found it hard to get a good job in academia, despite holding a PhD from MIT’s prestigious economics department, probably because her work showed that trade liberalization had slowed the rate of poverty reduction in rural India. While theoretical papers showing that freer trade could have such adverse effects were acceptable, studies that demonstrated the phenomenon empirically were met with skepticism.

The global financial crisis shattered both the prevailing consensus and the public’s trust. Clearly, the liberal orthodoxy had not worked for everyone in the US. Now-acceptable studies showed that middle-class manufacturing workers exposed to Chinese competition had been hit especially hard. “Obviously,” the accusation went, “the policymaking elites, whose friends and family were in protected service jobs, benefited from cheap imported goods and could not be trusted on trade.” In Europe, the free movement of goods, capital, services, and people within the single market were seen as serving the interests of the EU’s unelected bureaucrats in Brussels more than anyone else.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 31, 2023 at 8:48pm

-

Unlike China, which has developed its end-to-end supply chain solutions over the last four decades, India’s manufacturing sector has been small relative to its agricultural sector. India has yet to develop its capability to produce electronic parts domestically. India imported $12 billion worth of China-manufactured electronic parts in a five-month span last year, making up more than a quarter of its China imports. Netherlands-based Philips said in October that, despite the call to derisk from China, it will continue to source Chinese components including nuts, bolts, plastics, electronics, monitors, and other semi-finished goods for its operations around the world.

https://www.barrons.com/articles/india-bureaucracy-will-hold-back-e...

To develop a connected national market, the Indian government is building motorways, airports, and railroads to stimulate material and people movements between states. However, even when this new infrastructure is put in place, there will be wide gaps between states. GDP per person in Uttar Pradesh is around $4,000, compared to $10,000 in Kerala.

Besides the income gap, there is a cultural gap. Unlike China, where 92% of the population belongs to the Mandarin-speaking Han ethnic group, India has a very diverse population that speaks many languages. Cultural differences, language problems, and state-specific business regulations make expanding a business from one state to another a challenge.

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Improved US-Pakistan Ties: F-1 Visas For Pakistani Students Soaring

The F-1 visas for Pakistani students are soaring amid a global decline, according to the US government data. The US visas granted to Pakistani students climbed 44.3% in the first half of Fiscal Year 2025 (October 2024 to March 2025) with warming relations between the governments of the two countries. The number of visas granted to Indian students declined 44.5%, compared to 20% fewer US visas given to students globally in this period. The number of US visas granted to Pakistani…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on October 19, 2025 at 10:00am — 1 Comment

Major Hindu American Group Distances Itself From Modi's India

"We are not proxies for India in the US", wrote Suhag Shukla, co-founder and executive director of the Hindu American Foundation (HAF) in a recent article for The Print, an Indian media outlet. This was written in response to Indian diplomat-politician Shashi Tharoor's criticism that the Indian-American diaspora was largely silent on the Trump administration policies hurting India. …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on October 11, 2025 at 2:00pm

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network