PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Top One Percent: Are Hindus the New Jews in America?

Hindu Americans have surpassed Jewish Americans in education and rival them in household incomes. How did immigrants from India, one of the world's poorest countries, join the ranks of the richest people in the United States? How did such a small minority of just 1% become so disproportionately represented in the highest income occupations ranging from top corporate executives and technology entrepreneurs to doctors, lawyers and investment bankers? Indian-American Professor Devesh Kapur, co-author of The Other One Percent: Indians in America, explains it in terms of educational achievement. He says that an Indian-American is at least 9 times more educated than an individual in India. He attributes it to what he calls a process of "triple selection".

Hindu American Household Income:

A 2016 Pew study reported that more than a third of Hindus (36%) and four-in-ten Jews (44%) live in households with incomes of at least $100,000. More recently, the US Census data shows that the median household income of Indian-Americans, vast majority of whom are Hindus, has reached $127,000, the highest among all ethnic groups in America.

Median income of Pakistani-American households is $87.51K, below $97.3K for Asian-Americans but significantly higher than $65.71K for overall population. Median income for Indian-American households $126.7K, the highest in the nation.

|

|

|

Hindu Americans Education:

Indian-Americans, vast majority of whom are Hindu, have the highest educational achievement among the religions in America. More than three-quarters (76%) of them have at least a bachelors's degree. This high achieving population of Indian-American includes very few of India’s most marginalized groups such as Adivasis, Dalits, and Muslims.

By comparison, sixty percent of Pakistani-Americans have at least a bachelor's degree, the second highest percentage among Asian-Americans. The average for Asian-Americans with at least a bachelor's degree is 56%.

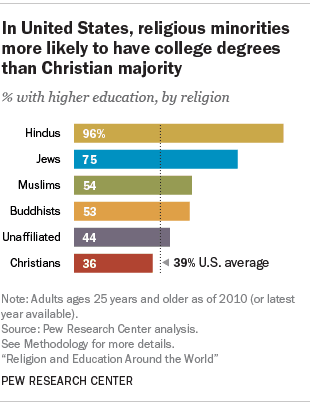

American Hindus are the most highly educated with 96% of them having college degrees, according to Pew Research. 75% of Jews and 54% of American Muslims have college degrees versus the US national average of 39% for all Americans. American Christians trail all other groups with just 36% of them having college degrees. 96% of Hindus and 80% of Muslims in the U.S. are either immigrants or the children of immigrants.

|

| US Educational Attainment By Religion Source: Pew Research |

Jews are the second-best educated in America with 59% of them having college degrees. Then come Buddhists (47%), Muslims (39%) and Christians (25%).

Triple Selection:

Devesh Kapur, a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania and co-author of The Other One Percent: Indians in America (Oxford University Press, 2017), explains the phenomenon of high-achieving Indian-Americans as follows: “What we learned in researching this book is that Indians in America did not resemble any other population anywhere; not the Indian population in India, nor the native population in the United States, nor any other immigrant group from any other nation.”

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Pakistani-Americans: Young, Well-educated and Prosperous

Hindus and Muslim Well-educated in America But Least Educated World...

What's Driving Islamophobia in America?

Pakistani-Americans Largest Foreign-Born Muslim Group in Silicon Va...

Caste Discrimination Among Indian-Americans in Silicon Valley

Islamophobia in America

Silicon Valley Pakistani-Americans

Pakistani-American Leads Silicon Valley's Top Incubator

Silicon Valley Pakistanis Enabling 2nd Machine Revolution

Karachi-born Triple Oscar Winning Graphics Artist

Pakistani-American Ashar Aziz's Fire-eye Goes Public

Two Pakistani-American Silicon Valley Techs Among Top 5 VC Deals

Pakistani-American's Game-Changing Vision

Minorities Are Majority in Silicon Valley

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 4, 2022 at 5:14pm

-

Neither Indian nor Pakistani universities make the top 100 world rankings.

All Indian-American CEOs here have studied in the US and earned advanced degrees in America without which they wouldn't advance.I bet these CEOs are a lot more rational than most of the Indian grads from IIT or anywhere else in India.These CEOs wouldn't make it to the top in America if they spewed the kind of hate and bigotry that is the norm in India.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 12, 2022 at 8:06am

-

Japan Needs Indian Tech Workers. But Do They Need Japan?

Recruiters call the push a crucial test of whether the world’s third-largest economy can compete with the U.S. and Europe for global talent.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/12/business/japan-indian-tech-worke...

Mr. Puranik said fellow Indians often called him for help with emergencies or conflicts — the wandering father with dementia who ends up in police custody, the daughter mistakenly stopped by border agents at the airport. He once even fielded a call from a worker who wanted to sue his Japanese boss for kicking him.

His own son, he said, was bullied in a Japanese school — by the teacher. Mr. Puranik said he repeatedly talked to the teacher, to no avail. “She would always try to make him a criminal,” he said, adding that some teachers “feel challenged if the kid is doing anything differently.”

A similar dynamic can sometimes be found in the workplace.

Many Indian tech workers in Japan say they encounter ironclad corporate hierarchies and resistance to change, a paradox in an industry that thrives on innovation and risk-taking.

“They want things in a particular order; they want case studies and past experience,” Mr. Puranik said of some Japanese managers. “IT doesn’t work like that. There is no past experience. We have to reinvent ourselves every day.”

---------

As it rapidly ages, Japan desperately needs more workers to fuel the world’s third-largest economy and plug gaps in everything from farming and factory work to elder care and nursing. Bending to this reality, the country has eased strict limits on immigration in hopes of attracting hundreds of thousands of foreign workers, most notably through a landmark expansion of work visa rules approved in 2018.

The need for international talent is perhaps no greater than in the tech sector, where the government estimates that the shortfall in workers will reach nearly 800,000 in the coming years as the country pursues a long-overdue national digitization effort.

The pandemic, by pushing work, education and many other aspects of daily life onto online platforms, has magnified the technological shortcomings of a country once seen as a leader in high tech.

Japanese companies, particularly smaller ones, have struggled to wean themselves from physical paperwork and adopt digital tools. Government reports and independent analyses show Japanese companies’ use of cloud technologies is nearly a decade behind those in the United States.

“As it happens to anyone who comes to Japan, you fall in love,” said Shailesh Date, 50, who first went to the country in 1996 and is now the head of technology for the American financial services company Franklin Templeton Japan in Tokyo. “It’s the most beautiful country to live in.”

Yet the Indian newcomers mostly admire Japan from across a divide. Many of Japan’s 36,000 Indians are concentrated in the Edogawa section of eastern Tokyo, where they have their own vegetarian restaurants, places of worship and specialty grocery stores. The area has two major Indian schools where children study in English and follow Indian curricular standards.

Nirmal Jain, an Indian educator, said she founded the Indian International School in Japan in 2004 for children who would not thrive in Japan’s one-size-fits-all public education system. The school now has 1,400 students on two campuses and is building a new, larger facility in Tokyo.

Ms. Jain said that separate schools were appropriate in a place like Japan, where people tend to keep their distance from outsiders.

“I mean, they are nice people, everything is perfect, but when it comes to person-to-person relationships, it’s kind of not there,” she said.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 13, 2023 at 10:34am

-

How India’s caste system limits diversity in science — in six charts

https://www.nature.com/immersive/d41586-023-00015-2/index.html

Data show how privileged groups still dominate many of the country’s elite research institutes.

This article is part of a Nature series examining data on ethnic or racial diversity in science in different countries. See also: How UK science is failing Black researchers — in nine stark charts.

Samadhan is an outlier in his home village in western India. Last year, he became the first person from there to start a science PhD. Samadhan, a student in Maharashtra state, is an Adivasi or indigenous person — a member of one of the most marginalized and poorest communities in India.

For that reason, he doesn’t want to publicize his last name or institution, partly because he fears that doing so would bring his social status to the attention of a wider group of Indian scientists. “They’d know that I am from a lower category and will think that I have progressed because of [the] quota,” he says.

The quota Samadhan refers to is also known as a reservation policy: a form of affirmative action that was written into India’s constitution in 1950. Reservation policies aimed to uplift marginalized communities by allocating quotas for them in public-sector jobs and in education. Mirroring India’s caste system of social hierarchy, the most privileged castes dominated white-collar professions, including roles in science and technology. After many years, the Indian government settled on a 7.5% quota for Adivasis (referred to as ‘Scheduled Tribes’ in official records) and a 15% quota for another marginalized group, the Dalits (referred to in government records as ‘Scheduled Castes’, and formerly known by the dehumanizing term ‘untouchables’). These quotas — which apply to almost all Indian research institutes — roughly correspond to these communities’ representation in the population, according to the most recent census of 2011.

But the historically privileged castes — the ‘General’ category in government records — still dominate many of India’s elite research institutions. Above the level of PhD students, the representation of Adivasis and Dalits falls off a cliff. Less than 1% of professors come from these communities at the top-ranked institutes among the 23 that together are known as the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), according to data provided to Nature under right-to-information requests (see ‘Diversity at top Indian institutions’; the figures are for 2020, the latest available at time of collection).

“This is deliberate” on the part of institutes that “don’t want us to succeed”, says Ramesh Chandra, a Dalit, who retired as a senior professor at the University of Delhi last June. Researchers blame institute heads for not following the reservation policies, and the government for letting them off the hook.

Diversity gaps are common in science in many countries but they take different forms in each nation. The situation in India highlights how its caste system limits scientific opportunities for certain groups in a nation striving to become a global research leader.

India’s government publishes summary student data, but its figures for academic levels beyond this don’t allow analyses of scientists by caste and academic position, and most universities do not publish these data. In the past few years, however, journalists, student groups and researchers have been gathering diversity data using public-information laws, and arguing for change. Nature has used some of these figures, and its own information requests, to examine the diversity picture. Together, these data show that there are major gaps in diversity in Indian science institutions.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 16, 2023 at 12:47pm

-

Indians are top earners in the US, even ahead of Americans; China, Pakistan miles behind

https://www.firstpost.com/world/indians-are-top-earners-in-the-us-e...

According to an American Community Survey, Indian-Americans (USD 100,500) have the highest median household income in the US. They are ahead of people from countries like Sri Lanka, Japan, China and Pakistan

Top American lawmaker Rich McCormick, while addressing the US House of Representatives, recently said that the Indian-Americans constitute about one per cent of the US population and pay about six per cent of the taxes.

What’s more interesting to know is the fact that Indians are the highest earning ethnic group in the US — ahead of people from countries like Pakistan, China and Japan.

According to US Census Bureau, 2013-15 American Community Survey, Indian-Americans (USD 100,500) have the highest median household income in the Joe Biden-led country. They are ahead of people from countries like Sri Lanka, Japan, China and Pakistan.

The data also highlights that 70 per cent of the Indian-American population in America holds a Bachelor’s degree, while the national average is just 28 per cent.

While this data is from an old survey, a more recent numbers also indicate the same thing.

According to an August 2021 report of Press Trust of India, Indians in the US, with an average household earning of USD 123,700 and 79 per cent of college graduates, have surpassed the overall American population in terms of wealth and college education.

As per the latest census data in the US, the number of people who identify as Asian in the United States nearly tripled in the past three decades, and Asians are now the fastest-growing of the nation’s four largest racial and ethnic groups, the PTI report stated.

Why Indians have highest median household income in the US?

Harsh Goenka, chairman of RPG Enterprises, took to Twitter to share a chart that shows Indian Americans having the highest median household income in the US. He asserted that Indians shine in the US because “we value good education and are the most educated ethnic group.”

“We work very hard along with being frugal in our habits… We are smart… We are in IT, engineering and medicine- the highest paying jobs,” he added.

How Median Household Income is calculated?

Household income usually refers to the combined gross income of all members of a household above a specified age, according to Investopedia.

The median is the middle number in a group. For example, if there are three incomes in one household of Rs 10,000, Rs 15,000 and Rs 20,000, in this case median income is Rs 15,000.

Domination of Indian-Americans in the US

In his first speech in the US House of Representatives, Rich McCormick urged for a streamlined immigration process. “I rise to this occasion to just appreciate my constituents, especially those who have immigrated from India. We have a very large portion of my community that’s made up of almost 100,000 People who have immigrated directly from India. One out of every five doctors in my community is from India. They represent some of the best citizens we have in America, we should make sure that we streamline the immigration process for those who come here to obey the law and pay their taxes.”

He added, “Although they make up about 1 per cent of American society, they pay about 6 per cent of the taxes. They are amongst the top producers, and they do not cause problems. They follow laws. They don’t have the problems that we see other people have when they come to the emergency room for overdoses and depression anxiety because they’re the most productive, most family oriented and the best of what represents American citizens. God bless my Indian constituents”.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on February 27, 2023 at 8:21am

-

#Indian-#Americans Rapidly Climbing in #US Politics. The relative wealth of Indian #immigrants and high #education levels have propelled a rapid #political ascent for 2nd & 3rd generations. #KamalaHarris #NikkiHaley #Hindu #SiliconValley #Tech #Pakistan https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/27/us/politics/indian-american-poli...

In 2013, the House of Representatives had a single Indian American member. Fewer than 10 Indian Americans were serving in state legislatures. None had been elected to the Senate. None had run for president. Despite being one of the largest immigrant groups in the United States, Americans of Indian descent were barely represented in politics.

Ten years later, the Congress sworn in last month includes five Indian Americans. Nearly 50 are in state legislatures. The vice president is Indian American. Nikki Haley’s campaign announcement this month makes 2024 the third consecutive cycle in which an Indian American has run for president, and Vivek Ramaswamy’s newly announced candidacy makes it the first cycle with two.

In parts of the government, “we’ve gone literally from having no one to getting close to parity,” said Neil Makhija, the executive director of Impact, an Indian American advocacy group.

Most Indian American voters are Democrats, and it is an open question how much of their support Ms. Haley might muster. In the past, when Indian Americans have run as Republicans, they have rarely talked much about their family histories, but Ms. Haley is emphasizing her background.

Activists, analysts and current and former elected officials, including four of the five Indian Americans in Congress, described an array of forces that have bolstered the political influence of Indian Americans.

------

Indians did not begin moving to the United States in large numbers until after a landmark 1965 immigration law. But a number of factors, such as the relative wealth of Indian immigrants and high education levels, have propelled a rapid political ascent for the second and third generations.

Advocacy groups — including Impact and the AAPI Victory Fund — have mobilized to recruit and support them, and to direct politicians’ attention to the electoral heft of Indian Americans, whose populations in states including Georgia, Pennsylvania and Texas are large enough to help sway local, state and federal races.

“It’s really all working in tandem,” said Raj Goyle, a former state lawmaker in Kansas who co-founded Impact. “There’s a natural trend, society is more accepting, and there is deliberate political strategy to make it happen.”

------

In retrospect, the watershed appears to have been 2016, just after then-Gov. Bobby Jindal of Louisiana became the first Indian American to run for president.

That was also the year (2016) Representatives Pramila Jayapal of Washington, Ro Khanna of California and Raja Krishnamoorthi of Illinois were elected, bringing the number of Indian Americans in the House from one — Representative Ami Bera of California, elected in 2012 — to four. It was also the year Kamala Harris became the first Indian American elected to the Senate.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 18, 2023 at 6:33pm

-

I won a birth lottery on caste, but learned fortune need not mean cruelty

Shree Paradkar

By Shree ParadkarSocial & Racial Justice Columnist

https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2023/04/15/i-won-a-birth-lotter...

I come from a Brahmin family. This means I won a birth lottery. It means that while other identities may pose barriers, caste is never one. In fact, in certain situations, it is the secret handshake that opens doors, sometimes literally.

Caste privilege looks like — among many things — never hesitating to say your last name, being considered to come from a “good family,” having a higher chance of a sheltered upbringing (innocence is prized but not granted to all women) and being treated with deference in public spaces.

Brahmins around me insist they are not casteist. They say they don’t even think about caste let alone know the names of various castes, yet their social circles are almost entirely made up of fellow Brahmins. They say that caste oppression is now reversed and that Brahmins are now the real victims, sidelined in the caste system.

These are debates without empirical data, backed up by an anecdote or two about an undeserving “lower caste” person getting this job or that. (For a Brahmin, everybody else is “lower caste.”) By various counts, Brahmins, who form about four to five per cent of the Hindu population, comprise half of Indian media decision-makers and at least a third of bureaucrats and judges. Meanwhile, according to Oxfam, Dalits’ life expectancy can be up to 15 years less than other groups.

If forced to discuss caste, Brahmins will often claim the orginal varna system was fluid at its founding thousands of years ago, again with no evidence that Dalits could ever have educated themselves enough to then be considered Brahmin. As Indian social justice advocate Dilip Mandal noted recently on Twitter Spaces, a discussion on caste is neither theological nor historical nor abstract. It’s about lived experiences today.

Being ignorant of caste is a marker of privilege. I, too, only learned of the details of the caste system thanks to the tireless advocacy of Equality Labs in the U.S. Understanding anti-Black racism awoke me to caste-based brutality. Of course, learning that one’s gloried background is the carrier of such cruelty causes harsh cognitive dissonance. Reckoning with this reality is painful, but that discomfort pales in comparison to the generations of trauma inflicted on the marginalized. There is also little point in guilt or self-hatred; both emotions, while wrenching, simply continue to centre on the self.

None of us are born with a ready-made analysis of oppression. None of us choose to be born into the identities we inherit. The least the holders of power can do is to sit quietly, listen, reflect — not “Am I complicit” but “In what ways am I complicit” — learn, make space. And then they should let go of the reins.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 23, 2023 at 4:31pm

-

'Hindutva Is Nothing But Brahminism'

https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/hindutva-is-nothing-but-...

The author (Kancha Ilaiah) of Why I Am Not A Hindu on his view that 'Dalitisation' alone can effectively challenge the threat of Brahminical fascism parading in the garb of Hindutva.

How would you characterise contemporary Hindutva? What is the relationship between Hindutva and the Dalit-Bahujans?

As Dr.Ambedkar says, Hindutva is nothing but Brahminism. And whether you call it Hindutva or Arya Dharma or Sanatana Dharma or Hindusim, Brahminism has no organic link with Dalit-Bahujan life, world-views, rituals and even politics. To give you just one example, in my childhood many of us had not even heard of the Hindu gods, and it was only when we went to school that we learnt about Ram and Vishnu for the very first time. We had our own goddesses, such as Pochamma and Elamma, and our own caste god, Virappa. They and their festivals played a central role in our lives, not the Hindu gods. At the festivals of our deities, we would sing and dance--men, women and all-- and would sacrifice animals and drink liquor, all of which the Hindus consider 'polluting'.

Our relations with our deities were transactional and they were rooted in the production process. For instance, our goddess Kattamma Maisa. Her responsibility is to fill the tanks with water. If she does it well, a large number of animals are sacrificed to her. If in one year the tanks dry up, she gets no animals. You see, between her and her Dalit-Bahujan devotees there is this production relation which is central.

----

In fact, many Dalit communities preserve traditions of the Hindu gods being their enemies. In Andhra, the Madigas enact a drama which sometimes goes on for five days. This drama revolves around Jambavanta, the Madiga hero, and Brahma, the representative of the Brahmins. The two meet and have a long dialogue. The central argument in this dialogue is about the creation of humankind. Brahma claims superiority for the Brahmins over everybody else, but Jambavanta says, 'No, you are our enemy'. Brahma then says that he created the Brahmins from his mouth, the Kshatriyas from his hands, the Vaishyas from his thighs, the Shudras from his feet to be slaves for the Brahmins, and of course the Dalits, who fall out of the caste system, have no place here. This is the Vedic story.

What you are perhaps suggesting is that Dalit-Bahujan religion can be used to effectively counter the politics of Brahminism or Hindutva. But Brahminism has this knack of co-opting all revolt against it, by absorbing it within the system.

It is true that although Dalit-Bahujan religious formations historically operated autonomously from Hindu forms, they have never been centralised or codified. Their local gods and goddesses have not been projected into universality, nor has their religion been given an all-India name. This is because these local deities and religious forms were organically linked to local communities, and were linked to local productive processes, such as the case of Virappa and Katamma Maisa whom I talked about earlier. But Brahminism has consistently sought to subvert these religious forms by injecting notions of 'purity' and 'pollution', hierarchy and untouchability even among the Dalit-Bahujans themselves, while at the same time discounting our religious traditions by condemning them as 'polluting' or by Brahminising them.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 9, 2023 at 7:57am

-

A third of India's most sought after engineering graduates leave the country

https://qz.com/a-third-of-indias-iit-graduates-leave-the-country-18...

https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31308/w31308.pdf

Banaras Hindu University saw a 540% spike in immigration among graduates after it was turned as an IIT in 2012

One-third of those graduating from the country’s prestigious engineering schools, particularly the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), migrate abroad.

Such highly-skilled persons account for 65% of the migrants heading to the US alone, a working paper (pdf) of the US-based National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) has concluded.

Nine out of 10 top scorers in the annual joint entrance examination held nationally for admission to the IITs and other reputed engineering colleges have migrated. Up to 36% of the top 1,000 scorers, too, have taken this path, according to the paper published this month.

In the US, there is a long list of IIT graduates now leading executives and CEOs. However, most immigrants move to the US as students and eventually join the US workforce. The NBER paper found that 83% of such immigrants pursue a Master’s degree or a doctorate.

“...through a combination of signaling and network effects, elite universities in source countries play a key role in shaping migration outcomes, both in terms of the overall propensity and the particular migration destination,” the report said.

India has 23 IITs across the country. The acceptance rates at most these hallowed institutions are lower than those of Ivy League colleges, especially at the most sought-after IITs at Kharagpur, Mumbai, Kanpur, Chennai, and Delhi. In 2023 alone, 189,744 candidates registered for the JEE, competing for only 16,598 seats.

Global economies are keen on highly skilled Indians

The US graduate program is a key pathway for migration, to recruit the “best and brightest,” the NBER report said.

Similarly, the UK’s High Potential Individual visa route lets graduates from the world’s top 50 non-UK universities, including the IITs, stay and work in the country for at least two years. For doctoral qualification, the work visa is for at least three years.

Fresh IIT graduates looking to move abroad are helped by a network of successful alumni and faculty already settled abroad, the report said. Some even provide access to particular programs where they have influence over admissions or hiring decisions.

The interesting case of Banaras Hindu University

In 2012, the century-old Banaras Hindu University (BHU), also India’s first central university, was accorded IIT status. The institute located in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, was elevated without any changes to its staff, curriculum, or admission system.

The NBER report studied 1,956 BHU students who graduated between 2005-2015 with a BTech, BPharm, MTech, or integrated dual degrees. It found a 540% increase in the probability of migration among graduates after the grant of the IIT status.

“...the quality of education/human capital acquired by the students in the cohorts before and after the change remained constant, while only the name of the university on the degree received differed,” the report said.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 13, 2023 at 1:06pm

-

India’s diaspora is bigger and more influential than any in history

Adobe, Britain and Chanel are all run by people with Indian roots

https://www.economist.com/international/2023/06/12/indias-diaspora-...

The Indian government, by contrast, has been—at least until Mr Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (bjp) took over—filled with people whose view of the world had been at least partly shaped by an education in the West. India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, studied at Cambridge. Mr Modi’s predecessor, Manmohan Singh, studied at both Oxford and Cambridge.

India’s claims to be a democratic country steeped in liberal values help its diaspora integrate more readily in the West. The diaspora then binds India to the West in turn. The most stunning example of this emerged in 2008, when America signed an agreement that, in effect, recognised India as a nuclear power, despite its never having signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (along with Pakistan and Israel). Lobbying and fundraising by Indian-Americans helped push the deal through America’s Congress.

The Indian diaspora gets involved in politics back in India, too. Ahead of the 2014 general election, when Mr Modi first swept to power, one estimate suggests more than 8,000 overseas Indians from Britain and America flew to India to join his campaign. Many more used text messages and social media to turn out bjp votes from afar. They contributed unknown sums of money to the campaign.

Under Mr Modi, India’s ties to the West have been tested. In a bid to reassert its status as a non-aligned power, India has refused to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and stocked up on cheap Russian gas and fertiliser. Government officials spew nationalist rhetoric that pleases right-wing Hindu hotheads. And liberal freedoms are under attack. In March Rahul Gandhi, leader of the opposition Congress party, was disqualified from parliament on a spurious defamation charge after an Indian court convicted him of criminal defamation. Meanwhile journalists are harassed and their offices raided by the authorities.

Overseas Indians help ensure that neither India nor the West gives up on the other. Mr Modi knows he cannot afford to lose their support and that forcing hyphenated Indians to pick sides is out of the question. At a time when China and its friends want to face down a world order set by its rivals, it is vital for the West to keep India on side. Despite its backsliding, India remains invaluable—much like its migrants.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 14, 2023 at 10:50am

-

TOP TALENT, ELITE COLLEGES, AND MIGRATION:

EVIDENCE FROM THE INDIAN INSTITUTES OF TECHNOLOGY

Prithwiraj Choudhury

Ina Ganguli

Patrick Gaulé

https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31308/w31308.pdf

We study migration in the right tail of the talent distribution using a novel dataset of Indian high

school students taking the Joint Entrance Exam (JEE), a college entrance exam used for

admission to the prestigious Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT). We find a high incidence of

migration after students complete college: among the top 1,000 scorers on the exam, 36% have

migrated abroad, rising to 62%for the top 100 scorers. We next document that students who

attended the original “Top 5” Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) were 5 percentage points

more likely to migrate for graduate school compared to equally talented students who studied in

other institutions. We explore two mechanisms for these patterns: signaling, for which we study

migration after one university suddenly gained the IIT designation; and alumni networks, using

information on the location of IIT alumni in U.S. computer science departments.

------

Highly skilled immigrants make important contributions to innovation and technology in

the United States. Often, they study in elite universities in their home countries before getting

advanced degrees abroad. For example, many successful Indian immigrants in the technology

industry—including Sundar Pichai, the CEO of Alphabet Inc./Google, and Arvind Krishna, the

CEO of IBM—are undergraduate alumni of the selective Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs).

Similarly, Chinese students in U.S. Ph.D. programs overwhelmingly come from a set of highly

selective Chinese universities (Gaulé and Piacentini, 2013).

In this paper, we study migration in the very right tail of the talent distribution for high

school students in India, focusing on the extent to which elite universities in their home country

facilitate migration. We focus on the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs). The IITs are

prestigious and highly selective technical universities with lower acceptance rates than Ivy League

colleges, particularly for the original five IIT Campuses.

1 Admission to the IITs is solely through

the Joint Entrance Exam (JEE), where nearly one million exam takers compete for less than ten

thousand spots. Desai, Kapur, McHale, and Rogers (2009) document anecdotal evidence related

to the role of elite institutions in India, such as the IITs and the All India Institute of Medical

Sciences, in facilitating skilled migration to the United States. IIT students have even been

described as “America’s most valuable import from India” (Leung, 2003).

Emigration is often difficult to observe from administrative datasets, and few surveys have

been conducted with a focus on top talent that are not selected on future success or mobility.

2 We

were able to overcome these challenges by leveraging the unanticipated public release of the names

and scores of JEE exam takers in 2010, combined with an intensive manual collection effort on

exam takers’ outcomes. The result is a novel dataset of high school students who took the JEE

exam, linked to college attended and later career, education, and migration outcomes. The data

provides individuals’ scores received on the exam and their national ranking. An important feature

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Pakistan's Rising Arms Sales to Developing Nations

Pakistan is emerging as a major arms supplier to developing countries in Asia and Africa. Azerbaijan, Myanmar, Nigeria and Sudan have all made significant arms purchases from Pakistan in recent years. Azerbaijan expanded its order for JF-17 Thunder Block III multi-role fighter jets from Pakistan from 16 to 40 aircraft. The recent order extends a 2024 contract worth $1.6 billion to modernize Baku’s airborne combat fleet to $4.6 billion. This makes Azerbaijan the largest export customer of…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on October 29, 2025 at 10:30am

Improved US-Pakistan Ties: F-1 Visas For Pakistani Students Soaring

The F-1 visas for Pakistani students are soaring amid a global decline, according to the US government data. The US visas granted to Pakistani students climbed 44.3% in the first half of Fiscal Year 2025 (October 2024 to March 2025) with warming relations between the governments of the two countries. The number of visas granted to Indian students declined 44.5%, compared to 20% fewer US visas given to students globally in this period. The number of US visas granted to Pakistani…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on October 19, 2025 at 10:00am — 1 Comment

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network