PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

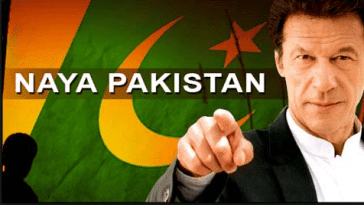

Pakistan Day: Will "Naya Pakistan" Be Truly Free?

Pakistan's Independence Day celebrations this year coincide with a momentous change in leadership. It has been brought about by the triumph of the insurgent Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf (PTI) over Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN) and Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), both regarded as dynastic political parties. PMLN and PPP are each controlled by a family. Pakistan's Prime Minister Elect Imran Khan is part of a generation that he says "grew up at a time when colonial hang up was at its peak." How will the acknowledgement of this upbringing affect Imran Khan's leadership of "Naya Pakistan"? Let's examine the answers to this question.

Colonial Era Education:

Imran Khan attended Aitchison College, an elite school established in Lahore by South Asia's colonial rulers to produce faithful civil servants during the British Raj. He then went on to graduate from Oxford University in England. Here's an excerpt of what he wrote in an article published by the Arab News on January 14, 2002:

"My generation grew up at a time when colonial hang up was at its peak. Our older generation had been slaves and had a huge inferiority complex of the British. The school I went to was similar to all elite schools in Pakistan. Despite gaining independent, they were, and still are, producing replicas of public schoolboys rather than Pakistanis.

I read Shakespeare, which was fine, but no Allama Iqbal — the national poet of Pakistan. The class on Islamic studies was not taken seriously, and when I left school I was considered among the elite of the country because I could speak English and wore Western clothes.

Despite periodically shouting ‘Pakistan Zindabad’ in school functions, I considered my own culture backward and religion outdated. Among our group if any one talked about religion, prayed or kept a beard he was immediately branded a Mullah.

Because of the power of the Western media, our heroes were Western movie stars or pop stars. When I went to Oxford already burdened with this hang up, things didn’t get any easier. At Oxford, not just Islam, but all religions were considered anachronism."

Colonized Minds:

It is refreshing to see Imran Khan's acknowledgement that Pakistan's elite schools are "producing replicas of public schoolboys rather than Pakistanis". Pakistan achieved independence from the British colonial rule 70 years ago. However, the minds of most of Pakistan's elites remain colonized to this day. This seems to be particularly true of the nation's western-educated "liberals" who dominate much of the intellectual discourse in the country. They continue to look at their fellow countrymen through the eyes of the Orientalists who served as tools for western colonization of Asia, Middle East and Africa. The work of these "native" Orientalists available in their books, op ed columns and other publications reflects their utter contempt for Pakistan and Pakistanis. Their colonized minds uncritically accept all things western. They often seem to think that the Pakistanis can do nothing right while the West can do no wrong. Far from being constructive, these colonized minds promote lack of confidence in the ability of their fellow "natives" to solve their own problems and contribute to hopelessness. The way out of it is to encourage more inquiry based learning and critical thinking.

Orientalism As Tool of Colonialism:

Dr. Edward Said (1935-2003), Palestine-born Columbia University professor and the author of "Orientalism", described it as the ethnocentric study of non-Europeans by Europeans. Dr. Said wrote that the Orientalists see the people of Asia, Africa and the Middle East as “gullible” and “devoid of energy and initiative.” European colonization led to the decline and destruction of the prosperity of every nation they ruled. India is a prime example of it. India was the world's largest economy producing over a quarter of the world's GDP when the British arrived. At the end of the British Raj, India's contribution was reduced to less than 2% of the world GDP.

Education to Colonize Minds:

In his "Prison Notebooks", Antonio Gramsci, an Italian Marxist theorist and politician, says that a class can exercise its power not merely by the use of force but by an institutionalized system of moral and intellectual leadership that promotes certain ideas and beliefs favorable to it. For Gramsci "cultural hegemony" is maintained through the consent of the dominated class which assures the intellectual and material supremacy of the dominant class.

In "Masks of Conquest", author Gauri Viswanathan says that the British curriculum was introduced in India to "mask" the economic exploitation of the colonized. Its main purpose was to colonize the minds of the natives to sustain colonial rule.

Cambridge Curriculum in Pakistan:

The colonial discourse of the superiority of English language and western education continues with a system of elite schools that uses Cambridge curriculum in Pakistan.

Over 270,000 Pakistani students from elite schools participated in Cambridge O-level and A-level International (CIE) exams in 2016, an increase of seven per cent over the prior year.

Cambridge IGCSE exams is also growing in popularity in Pakistan, with enrollment increasing by 16% from 10,364 in 2014-15 to 12,019 in 2015-16. Globally there has been 10% growth in entries across all Cambridge qualifications in 2016, including 11% growth in entries for Cambridge International A Levels and 8 per cent for Cambridge IGCSE, according to Express Tribune newspaper.

The United Kingdom remains the top source of international education for Pakistanis. 46,640 students, the largest number of Pakistani students receiving international education anywhere, are doing so at Pakistani universities in joint degree programs established with British universities, according to UK Council for International Student Affairs.

At the higher education level, the number of students enrolled in British-Pakistani joint degree programs in Pakistan (46,640) makes it the fourth largest effort behind Malaysia (78,850), China (64,560) and Singapore (49,970).

Teach Critical Thinking:

Pakistani educators need to see the western colonial influences and their detrimental effects on the minds of youngsters. They need to improve learning by helping students learn to think for themselves critically. Such reforms will require students to ask more questions and to find answers for themselves through their own research rather than taking the words of their textbook authors and teachers as the ultimate truth.

Summary:

It is refreshing to see Imran Khan's acknowledgement that Pakistan's elite schools are "producing replicas of public schoolboys rather than Pakistanis". The minds of most of Pakistan's elite remain colonized 70 years after the British rule of Pakistan ended in 1947. They uncritically accept all things western. A quick scan of Pakistan's English media shows the disdain the nation's western educated elites have for their fellow countryman. Far from being constructive, they promote lack of confidence in their fellow "natives" ability to solve their own problems and contribute to hopelessness. Their colonized minds uncritically accept all things western. They often seem to think that the Pakistanis can do nothing right while the West can do no wrong. Unless these colonized minds are freed, it will be difficult for the people of Pakistan to believe in themselves, have the confidence in their capabilities and develop the national pride to lay the foundation of a bright future. The best way to help free these colonized minds is through curriculum reform that helps build real critical thinking.

Here's an interesting discussion of the legacy of the British Raj in India as seen by writer-diplomat Shashi Tharoor:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dN2Owcwq6_M

Related Links:

PTI's Triumph Over Dynastic Political Parties

How Can Pakistan Avoid Recurring BoP Crises?

Dr. Ata ur Rehman Defends Higher Education Reform

Pakistan's Rising College Enrollment Rates

Pakistan Beat BRICs in Highly Cited Research Papers

Launch of "Eating Grass: Pakistan's Nuclear Program"

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on February 10, 2019 at 7:45pm

-

Military Might: Pakistan’s Continued Struggle with Democracy

Zahra Chaudhry February 10, 2019

http://thepolitic.org/military-might-pakistans-continued-struggle-w...Syeda Munnaza lives in Pakistan, in the bustling Lahore locality of Iqbal Town. There, she runs the Mehmod Hamid Welfare Memorial Society, a nonprofit that provides skills based employment training to locals, especially women and girls.

Munnaza’s house is divided on the political front: her three children, ranging in age from fifteen to twenty five, are huge fans of the new prime minister, Imran Khan. Munnaza herself is a loyal supporter of the former premier, Nawaz Sharif, and his party, the Pakistan Muslim League-N (PMLN). Ask her about the July 2018 election, and she’ll tell you it was entirely rigged in favor of Khan.

Nawaz Sharif’s career has been a tumultuous one since he first appeared on Pakistan’s political scene in the 1990s; he has served as prime minister three times without ever completing a full term. Most recently, in July 2017, Sharif resigned from his post after being declared unfit for office by the Supreme Court due to corruption scandals. Subsequently, the country voted overwhelmingly for the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) party, and PTI’s Chairman, Imran Khan, became Prime Minister. Khan ran on anti-establishment and vehemently anti-corruption rhetoric.

Sarah Khan, a postgraduate associate at the Yale Macmillan Center and researcher on gender and politics in South Asia, told The Politic, “The demographic pool of PTI supporters tends to be more educated, more on the higher end of the income spectrum, and also younger…but what we’ve seen in 2018 is a broader support for the PTI.”

Fahd Humayun, a PhD candidate at Yale, studies political behavior and regimes. He says this broader national support stemmed from Khan’s ability to portray himself as “an anti-status quo force—someone to be reckoned with”—while also focusing on the same issues that Sharif “had traditionally focused on.”

Humayun added, “Imran Khan’s not a new addition on Pakistan’s political landscape. He’s been around since the 1990s.” What made him an appealing “outsider,” however, is that he was a viable third option to a public increasingly weary with the country’s two other major political parties, the PMLN and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP).

While many are hopeful that Prime Minister Khan will follow through on his pledge to deliver a “New Pakistan,” one with welfare programs, a thriving economy, and an improved reputation on the international stage, others remain skeptical.

In an interview with The Politic, Munnaza said, in Urdu, that her kids “find establishment politicians to be foolish, uneducated, [and] problematic.”

She remains unconvinced by their argument, saying she voted for the PMLN because of “all the work” Sharif has “done for the people” in Lahore; she cited renovations and technological upgrades at government hospitals and improvements to the city’s education system. Munnaza isn’t alone in feeling indebted to Sharif and his party; the PMLN won 61 in the National Assembly, out of a total 272—corruption scandals and all. They came in second to the PTI.

“[I] would never say that I am going to stick with Nawaz Sharif and his party no matter what. If Imran Khan…wanted to do anything [for us], or if he was capable of it, then we would welcome change. But the way by which he came to power was extremely wrong,” Munnaza said.

She says that in a country like Pakistan, where corruption is a widespread problem, she doesn’t understand why Sharif’s particular case was pursued so rigorously.

In 2017, Sharif was disqualified from office by the Supreme Court after the Panama Papers showed his family’s ties to undisclosed properties abroad and offshore accounts. Sharif and his daughter were convicted on corruption related charges and received lengthy prison sentences just weeks before the 2018 elections.

Munnaza is doubtful that democratic institutions alone were responsible for the corruption crackdown and suspects election interference.

Niloufer Siddiqui GRD ‘17 is an assistant professor of political science at the State University of New York-Albany and a researcher in political violence in Pakistan. Siddiqui said, “People will ask whether or not elections are free and fair in Pakistan. Polling day rigging is very unlikely. Nobody is changing people’s votes at the booth.” But “pre-poll rigging” is an issue.

Sarah Khan explains that pre-poll rigging is when the military engages in “controlling the environment and distribution of information that allows voters to make informed decisions.”

Siddiqui told The Politic, “All the cases that churned out against Nawaz Sharif are likely to have been influenced by the military. In fact, the tribunal that found him guilty had two military members [on it]…”

She added, “… a series of steps were taken that ensured that he would no longer be a key player. All of this happened within weeks of the election.”

Khan and his supporters have celebrated Sharif’s ousting and arrest as an indication of the start of a new era in Pakistani politics where powerful people will be held accountable.

The consensus among sources who spoke to The Politic is that Sharif lost favor with the military establishment by taking control over foreign policy. In 2013, he told an audience at the US Institute of Peace that trying to improve Pakistan’s relationship with India was one of his “favorite subjects.” In December 2015, Indian Prime Minister Modi visited Sharif’s private residence in Raiwind. This was the first time an Indian premier had visited Pakistan in more than a decade.

Siddiqui told The Politic that because foreign policy had historically been “under the military sphere of influence,” they felt Sharif had “overstepped.”

It is less clear, however, why the military chose to support Khan. His campaign centered around radically transforming most every aspect of governance–including Pakistan’s international relations. In December 2018, Prime Minister Khan told The Washington Post that Pakistan would not be the United States’ “hired gun” anymore.

Sarah Khan told The Politic, “It is…a bit of a puzzle as to why they would support Imran Khan, who is known to be perhaps stubborn or volatile…” On the other hand, she believes it makes sense that the military tried to support the “party that was already electorally viable,” something the PTI “very much was.”

Military intervention took on a few different forms, including restricting freedom of the press. For years, there has been pressure for Pakistani journalists to self-censor to please the military establishment.

During the 2018 campaign, Humayun says Khan received more TV time and more coverage by major national newspapers like Dawn News. In June 2018, Gul Bukhari, a columnist for The Nation and a prominent critic of the military, was abducted and held for four hours in a military cantonment in Lahore. She credits the public outcry on social media for her relatively prompt release.

Matiullah Jan, another critic of the military apparatus and former anchor on Waqt News, had his car’s windshield pelted with large rocks by motorcyclists in 2017. Jan called it a “pre-planned attack.”

Some also allege that the military called on popular politicians—or “electables”—from other parties to run under the PTI ticket. Lobbying for electables is a common strategic move in Pakistan to win in constituencies where voters show more loyalty to an individual than a party.

Siddiqui told The Politic, “My interviews with people that I know…seem to suggest that a lot of people were getting phone calls, again from the powers that be, to switch their support to the PTI.”

During the general elections, 46 electable candidates ran under the PTI ticket and 23 of them won their seats; most of the winners represent areas within the PMLN stronghold of Punjab. Khan said candidates joined the PTI because the other parties had failed to deliver.

It’s important to remember that Khan enjoyed a great deal of popular support from people like Munnaza’s children, who were inspired by his message of reform and progress.

Since 2013, his party has governed the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPK) through a coalition with religious parties. In 2018, the PTI won a historic re-election and majority in the province, where incumbents are generally voted out. Siddiqui believes this “kind of indicates the PTI is doing something right.”

Now, as Prime Minister, Khan has to turn Pakistan into an “Islamic welfare state,” as he said he would, while dealing with the country’s perilous economic crisis. The crisis is driven by a national account deficit in the billions, making it virtually impossible for Khan to run the government without foreign loans from sources like Saudi Arabia and China. He has yet to reach a bailout deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Munnaza wants to see economic relief and political progress, even though she doubts Khan’s ability to enact real change; “The poor people here aren’t constructing homes, or driving cars, or sending their kids to prestigious schools; they are working hard just to buy their flour and sugar.”

Munnaza believes, at the end of the day, Sharif and Khan don’t matter. What matters is helping the country’s poor afford a dignified life. For the good of the people she works with, she’s praying for Khan’s success

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 6, 2019 at 4:34pm

-

The Enlightenment’s Dark Side

How the Enlightenment created modern race thinking, and why we should confront it.

By JAMELLE BOUIE

https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2018/06/taking-the-enlightenmen...

The Enlightenment is having a renaissance, of sorts. A handful of centrist and conservative writers have reclaimed the 17th- and 18th-century intellectual movement as a response to nationalism and ethnic prejudice on the right and relativism and “identity politics” on the left. Among them are Jordan Peterson, the Canadian psychologist who sees himself as a bulwark against the forces of “chaos” and “postmodernism”; Steven Pinker, the Harvard cognitive psychologist who argues, in Enlightenment Now, for optimism and human progress against those “who despise the Enlightenment ideals of reason, science, humanism, and progress”; and conservative pundit Jonah Goldberg, who, in Suicide of the West, argues in defense of capitalism and Enlightenment liberalism, twin forces he calls “the Miracle” for creating Western prosperity.

In their telling, the Enlightenment is a straightforward story of progress, with major currents like race and colonialism cast aside, if they are acknowledged at all. Divorced from its cultural and historical context, this “Enlightenment” acts as an ideological talisman, less to do with contesting ideas or understanding history, and more to do with identity. It’s a standard, meant to distinguish its holders for their commitment to “rationalism” and “classical liberalism.”

But even as they venerate the Enlightenment, these writers actually underestimate its influence on the modern world. At its heart, the movement contained a paradox: Ideas of human freedom and individual rights took root in nations that held other human beings in bondage and were then in the process of exterminating native populations. Colonial domination and expropriation marched hand in hand with the spread of “liberty,” and liberalism arose alongside our modern notions of race and racism.

It took the scientific thought of the Enlightenment to create an enduring racial taxonomy and the “color-coded, white-over-black” ideology with which we are familiar.

These weren’t incidental developments or the mere remnants of earlier prejudice. Race as we understand it—a biological taxonomy that turns physical difference into relations of domination—is a product of the Enlightenment. Racism as we understand it now, as a socio-political order based on the permanent hierarchy of particular groups, developed as an attempt to resolve the fundamental contradiction between professing liberty and upholding slavery. Those who claim the Enlightenment’s mantle now should grapple with that legacy and what it means for our understanding of the modern world.

To say that “race” and “racism” are products of the Enlightenment is not to say that humans never held slaves or otherwise classified each other prior to the 18th century. Recent scholarship shows how proto- and early forms of modern race thinking (you could call them racialism) existed in medieval Europe, with near-modern forms taking shape in the 15th and 16th centuries. In Spain, for example, we see the turn from anti-Judaism to anti-Semitism, where Jewish ancestry itself was grounds for suspicion, versus Jewish practice. And as historian George Fredrickson notes in Racism: A Short History, “the prejudice and discrimination directed at the Irish on one side of Europe and certain Slavic peoples on the other foreshadowed the dichotomy between civilization and savagery that would characterize imperial expansion beyond the European continent.” One can find nascent forms of all of these ideas in antiquity—indeed, early modern thinkers drew from all of these sources to build our notion of race.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 6, 2020 at 10:02pm

-

#WhiteSupremacists: "White people are the best thing that ever happened to the world... How dare historically oppressed minorities in this country (#UnitedStates) recall the transgressions of their oppressors?" #BlackLivesMattters #MuslimLivesMatter https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/05/opinion/trump-monuments.html?smi...As Donald Trump gave his race-baiting speeches over the Fourth of July weekend, hoping to rile his base and jump-start his flagging campaign for re-election, I was forced to recall the ranting of a Columbia University sophomore that caught the nation’s attention in 2018.In the video, a student named Julian von Abele exclaims, “We built the modern world!” When someone asks who, he responds, “Europeans.”Von Abele goes on:“We invented science and industry, and you want to tell us to stop because oh my God, we’re so baaad. We invented the modern world. We saved billions of people from starvation. We built modern civilization. White people are the best thing that ever happened to the world. We are so amazing! I love myself! And I love white people!”He concludes: “I don’t hate other people. I just love white men.”Von Abele later apologized for “going over the top,” saying, “I emphasize that my reaction was not one of hate” and arguing that his remarks were taken “out of context.” But the sentiments like the one this young man expressed — that white men must be venerated, regardless of their sins, in spite of their sins, because they used maps, Bibles and guns to change the world, and thereby lifted it and saved it — aren’t limited to one college student’s regrettable video. They are at the root of patriarchal white supremacist ideology.To people who believe in this, white men are the heroes in the history of the world. They conquered those who could be conquered. They enslaved those who could be enslaved. And their religion and philosophy, and sometimes even their pseudoscience, provided the rationale for their actions.It was hard not to hear the voice of von Abele when Trump stood at the base of Mount Rushmore and said, “Seventeen seventy-six represented the culmination of thousands of years of Western civilization and the triumph not only of spirit, but of wisdom, philosophy and reason.” He continued later, “Our nation is witnessing a merciless campaign to wipe out our history, defame our heroes, erase our values and indoctrinate our children.”Refer your friends to The Times.They’ll enjoy our special rate of $1 a week.To be clear, the “our” in that passage is white people, specifically white men. Trump is telling white men that they are their ancestors, and that they’re now being attacked for that which they should be thanked.The ingratitude of it all.How dare historically oppressed minorities in this country recall the transgressions of their oppressors? How dare they demand that the whole truth be told? How dare they withhold their adoration of the abominable?At another point, Trump said of recent protests:“This left-wing cultural revolution is designed to overthrow the American Revolution. In so doing, they would destroy the very civilization that rescued billions from poverty, disease, violence and hunger, and that lifted humanity to new heights of achievement, discovery and progress.In fact, many of the protesters are simply pointing out the hypocrisy of these men, including many of the founders, who fought for freedom and liberty from the British while simultaneously enslaving Africans and slaughtering the Indigenous.But, Trump, like white supremacy itself, rejects the inclusion of this context. As Trump put it:“Against every law of society and nature, our children are taught in school to hate their own country, and to believe that the men and women who built it were not heroes, but that were villains. The radical view of American history is a web of lies — all perspective is removed, every virtue is obscured, every motive is twisted, every fact is distorted, and every flaw is magnified until the history is purged and the record is disfigured beyond all recognition.”In fact, the record is not being disfigured but corrected.According to Trump: “This movement is openly attacking the legacies of every person on Mount Rushmore. They defile the memory of Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln and Roosevelt.”Is it a defilement to point out that George Washington was an enslaver who signed a fugitive slave act and only freed his slaves in his will, after he was dead and no longer had earthly use for them?Is it a defilement to point out that Thomas Jefferson enslaved over 600 human beings during his life, many when he wrote the Declaration of Independence, and that he had sex with a child whom he enslaved — I call it rape — and even enslaved the children she bore for him?Is it a defilement to recall that during the Lincoln-Douglas debates Abraham Lincoln said:“I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the Black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which in my judgment will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong, having the superior position.”Is it defilement to recall that Theodore Roosevelt was a white supremacist, supporter of eugenics and an imperialist? As Gary Gerstle, a professor of American history at the University of Cambridge, once put it, “He would have had no patience with the Indigenous and original inhabitants of a sacred American space interfering with his conception of the American sublime.”

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 8, 2020 at 7:12am

-

VS Naipaul: Colonialism in fact, fiction, and the flesh

Naipaul personified what European colonialism, racist to the very core of its logic, had done to his and to our world.

https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/naipaul-colonialism-fact-...

VS Naipaul has died. VS Naipaul was a cruel man. The cruelty of colonialism was written all over him - body and soul.

VS Naipaul was a scarred man. He was the darkest dungeons of colonialism incarnate: self-punishing, self-loathing, world-loathing, full of nastiness and fury. Derek Walcott famously said of Naipaul that he commanded a beautiful prose "scarred by scrofula". That scrofula was colonialism.

Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul had abbreviated his history to palatable capitalised initials the British could pronounce. He was born in rural Trinidad in 1932, where the British had ruled since 1797, adding Tobago to it in 1814. By 1889 the two colonies were combined and Indian labourers - of whom Naipaul was a descendant - were brought in to toil on sugar plantations. He was born to this colonial history and all its postcolonial consequences.

By 1950 Naipaul was at Oxford on a government scholarship, just as the supreme racist Sir Winston Churchill was to start his second term as prime minister. Can you fathom an 18-year old Indian boy from Trinidad at Oxford in Churchill's England? You might as well be a Muslim Mexican bellboy at Trump Tower.

In a famous passage the late Edward Said wrote of Naipaul: "The most attractive and immoral move, however, has been Naipaul's, who has allowed himself quite consciously to be turned into a witness for the Western prosecution." This alas was far worse than mere careerism. Naipaul was, at his best and his worst, a witness for the Western prosecution. He did not fake it. He was the make of it.

Naipaul personified what European colonialism, racist to the very core of its logic, had done to his and to our world. He basked in what the rest of us loathe and defy. He made of his obsequious submission to colonialism a towering writing career. He was Aime Cesaire, Frantz Fanon, James Baldwin, CLR James and Edward Said gone bad. In them we see defiance of the cruel colonial fate. In him we see someone bathing naked in that history. In them we see the beauty of revolt, in him the ugliness of impersonating colonial cruelty.

Naipaul saw the world through the pernicious vision British colonialism had invested and impersonated in him. He became a ventriloquist for the nastiest cliches European colonialism had devised to rule the world with arrogance and confidence. He proved them right. He wrote, as CLR James rightly said, "what the whites want to say but dare not". This of course was before Donald Trump's America and Boris Johnson's England - where the racist whites are fully out of their sheets and hoods carrying their torches, burning their crosses, and looking for their letterboxes in the streets of Charlottesville and London.

--------------

In both his brilliance and in his banality, in his mastery of the English prose and cruelty of the vision he saw through it, VS Naipaul was a witness, as Edward Said rightly wrote. But under what Said saw as "witness for the Western prosecution" dwelled a much nastier truth. Naipaul was the walking embodiment of European colonialism - in fact, fiction, and flesh. He was a product of that world - in his fiction he mapped its global spectrum, and in his person, he thrived and made a long lucrative career proving all its bigoted banalities right.

We may never see the likes of VS Naipaul again. May we never see the likes of VS Naipaul again.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 8, 2020 at 7:28am

-

Epithets for VS Naipaul:

https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/naipaul-colonialism-fact-...

self-punishing, self-loathing, world-loathing

In a famous passage the late Edward Said wrote of Naipaul: "The most attractive and immoral move, however, has been Naipaul's, who has allowed himself quite consciously to be turned into a witness for the Western prosecution." This alas was far worse than mere careerism. Naipaul was, at his best and his worst, a witness for the Western prosecution. He did not fake it. He was the make of it.

ventriloquist for the nastiest cliches European colonialism had devised to rule the world with arrogance and confidence

He proved them right. He wrote, as CLR James rightly said, "what the whites want to say but dare not". This of course was before Donald Trump's America and Boris Johnson's England - where the racist whites are fully out of their sheets and hoods carrying their torches, burning their crosses, and looking for their letterboxes in the streets of Charlottesville and London.

He indeed wrote the English prose masterfully, but of the slavery of a mind suspicious of triumphant resistance. James Baldwin also wrote English prose beautifully, as did Edward Said, but reading them ennobles our souls, reading Naipaul is an exercise in self-flagellation.

Naipaul was an Indian Uncle Tom catapulted to the Trinidad corner of British colonialism - exuding the racist stereotypes and prejudices his British masters had taught him to believe about himself and his people.

Yes he was a racist bigot - the finest specimen of racism and bigotry definitive to the British colonialism that crafted his prose, praised his poise and knighted him at one and the same time.

He was a misogynist for that was what the British liberal imperialism had taught him he was. He acted the role to perfection. He crafted a dark soul in himself to prove his racist masters right. When he wrote of our criminalities his masters loved it, "you see he is one of them but he writes our language so well", and when he acted like a brute his masters sniggered and said, "you see still the Indian from Trinidad". For them he was win-win, for us, lose-lose.

Naipaul loathed Trinidad and he detested England - he wanted to hide where came from and destroy the place where he could not call his. He belonged to nothing and to nowhere. He sought refuge at his writing desk. In his first three books - The Mystic Masseur (1957), The Suffrage of Elvira (1958) and Miguel Street (1959) he retrieved what was left of his Caribbean childhood. In A House for Mr Biswas (1961) he sought to project his relations with his own father in what his admirers consider his masterpiece. In his published correspondences with his father, Between Father and Son: Family Letters (1999), he crafted and killed his parentage in one literary move.Throughout his travels - in Africa he saw darkness, in India banality and destitution, in Muslim lands fanaticism and stupidity. The world, wherever he went, was the extension of his Trinidad, the darkened shadows of his own brutally colonised soul.

I read his Among the Believers (1981) cover to cover when I was writing my book on Iranian resolution - shaking with disgust at his steady course of stupidity, ignorance, and flagrant racism. He knew next to nothing about Iran or any other Muslim country he visited. In all of them he was a vicious Alice in a whacky wonderland of his own making. How dare he, I remember thinking, writing with such wanton ignorance about nations and their brutalised destines, their noble struggles, their small but lasting triumphs!

In both his brilliance and in his banality, in his mastery of the English prose and cruelty of the vision he saw through it, VS Naipaul was a witness, as Edward Said rightly wrote. But under what Said saw as "witness for the Western prosecution" dwelled a much nastier truth. Naipaul was the walking embodiment of European colonialism - in fact, fiction, and flesh. He was a product of that world - in his fiction he mapped its global spectrum, and in his person, he thrived and made a long lucrative career proving all its bigoted banalities right.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 8, 2020 at 10:03am

-

Literature after the British Empire: V.S. Naipaul’s story

https://www.uncomfortableoxford.co.uk/post/literature-after-the-bri...

When we think of colonialism, we often envision images of sailing ships, bloody wars, and trading networks. Yet British settlers brought more than weapons, chains, and markets to foreign lands. They also brought their own cultural beliefs. When Britain formed colonies, it taught its language, its religion, and its literature to the peoples it colonized. These imposed education systems raise many questions. What influence did learning about British culture or reading British literature have on the students of the colonies? How does this education relate to the physical process of colonization? How were education systems in former colonies reformed after they gained independence?

The story of one Oxford alumnus who won the 2001 Nobel Prize in Literature, V.S. Naipaul, provides a few insights. Of Indian heritage, Naipaul grew up in the (then) British colony Trinidad and Tobago in the mid-1900s. He earned a government scholarship and attended Oxford to read English Literature before pursuing a career as a writer. Cultural tensions haunt his works.

In his Nobel lecture, Naipaul reflects on his cultural identity. He describes growing up feeling disconnected from Indian traditions and the Hindi language. In his colonial schooling, he recalls learning abstract facts about foreign lands and developing an identity filled with “areas of darkness”. He remembers having very few cultural models during his early writing career, for most of the authors he had studied in high school and at Oxford were European.

Naipaul’s experience is similar to those of many students growing up in colonies. In his influential essay, “Decolonising the Mind,” Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o describes how Britain developed as the cultural center of its empire through imposing English language and literature in the colonies’ education system. In Kenyan schools during the twentieth century, for instance, schools beat and ridiculed children for speaking Gĩkũyũ instead of English. English, as he notes, “became the measure of intelligence and ability in the arts, the science, and all the other branches of learning.”

This language and culture issue is a major topic of exploration in the works of authors from colonized societies in the 20th century, many of whom wrote in English. These works are termed Postcolonial Literature, which is an encompassing term referring to literature from nations shaped in any number of ways by colonialism.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o summarizes this issue succinctly: “The domination of a people’s language by the languages of the colonising nations was crucial to the domination of the mental universe of the colonized.” For the author, the solution is simple: write in one’s own native language. For others, such as the Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, the solution is to adapt English for their own culture’s nuances.

For Naipaul, there appeared to be no solution. After his studies at Oxford, he later travelled to his homeland India, and around the Caribbean region where he grew up, to gain a clearer sense of his historical roots. He also spent time researching these countries' histories. These experiences inspired him to delve into racial and social complexities in his creative writing, illuminating areas of darkness and giving him insight into his heritage: aspects that his colonial education had severed him from. When reflecting on his writing career, Naipaul said that “the aim has always been to fill out my world picture, and the purpose comes from my childhood: to make me more at ease with myself.” His characters, however, never seem to feel culturally at ease. Yet, the author also cautioned against comparing an author’s biographical details with his literary creativity.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 8, 2020 at 10:03am

-

Literature after the British Empire: V.S. Naipaul’s story

https://www.uncomfortableoxford.co.uk/post/literature-after-the-bri...

His novel Mimic Men (1967) explores a colonial politician’s life: it compiles snapshots of his education in London, his earlier childhood in the Caribbean, and his failed political career. A key theme in Naipaul’s work is the inauthenticity of his Caribbean characters, who are cut-off from their heritage. They lack cultural identities and mimic the condition of being human, for they are neither a part of their lost native cultures nor a part of European society. They constantly strive for the impossible aim of being political equals with their former colonizers, developing a loathing for other colonized people and a deep rage arising from powerlessness.

Another of Naipaul’s novels that addresses the colonized’s attempt to construct an authentic identity independent of British culture is his later work, A Bend in the River (1979). This tale follows the disillusionment of a businessman of Indian heritage living in an African nation. Many of his characters in this story similarly mimic the tastes and habits of their colonizers, including Indar, who heads to London for his education and idealizes British culture. Yet corruption lies at the heart of many colonized characters and of the new nation’s government. Though the independent nation attempts to distinguish itself from Europe, it remains a shadow. Naipaul’s characters appear never to escape colonial influences.

In “Decolonising the mind,” Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o describes this sense of hopelessness and disillusionment as an inevitable consequence of writing in English and valuing British culture at the expense of one’s own. Yet the link between English literature and England’s colonial legacy continues to spark debate. Some, like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, claim that literature is both a reflection of and a shaping force for a society’s cultural and political landscape. Others argue that literature and politics are distinct fields.

The Bodleian Library, Oxford

As the leading university in England during the country’s colonial period from the 17th to 20th centuries, Oxford was a hotspot for literary discussions and future writers. This prominent educational institution helped to define a collection of important English fiction called the “canon”. The literary canon represented the best literature of English culture, which was taught in the colonies. The institution’s prestige also drew and continues to draw ambitious students from (former) colonies, like Naipaul.

Today at Oxford, the field of Postcolonial Literature is a growing area of research that is drawing increasingly more attention. This rise in attention is in line with the ongoing process of global decolonization. Initiatives like the “Decolonising the English Faculty Open Letter” at the University of Cambridge in 2017 continue to advocate for a more nuanced appreciation of how language and literature shape politics.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 11, 2022 at 5:45pm

-

This year over four million Pakistani kids will turn 18. Of these, less than 25pc will graduate from the intermediate stream and about 30,000 will graduate from the O- and A-level stream. Over 3m kids, or 75pc, will not have finished 12 years of schooling. (Half of all kids in Pakistan are out of school.) These 30,000 kids from A-levels will dominate our top universities, many will study abroad and go on to become leaders. That’s less than 1pc of all 18-year-olds. These are the only Pakistanis for whom Pakistan works. But it gets worse.

by Miftah Ismail

https://www.dawn.com/news/1720082

---------

IN a Tedx talk I gave last year, I argued that Pakistan shouldn’t be called the Islamic Republic but rather the One Per Cent Republic. Opportunities, power and wealth here are limited to the top one per cent of the people. The rest are not provided opportunities to succeed.

Pakistan’s economy thus only relies on whatever a small elite can achieve. It remains underdeveloped as it ignores the talent of most in the country.

Suppose we had decided to select our cricket team only from players born in the second week of November. That would always have produced a weak team as it would only be selecting from 2pc of the population. Our teams wouldn’t have benefited from the talents of many of the greats we have had over the years. This is the same unfair and irrational way we choose our top people. And just as our team would have kept losing, so we as a nation keep losing.

--------------

There are around 400,000 schools in Pakistan. Yet in some years half of our Supreme Court judges and members of the federal cabinet come from just one school: Aitchison College in Lahore. Karachi Grammar School provides an inordinate number of our top professionals and richest businessmen. If we add the three American schools, Cadet College Hasanabdal and a few expensive private schools, maybe graduating 10,000 kids in total, we can be sure that these few kids will be at the top of most fields in Pakistan in the future, just as their fathers are at the very top today.

Five decades ago, Dr Mahbub ul Haq identified 22 families who controlled two-thirds of listed manufacturing and four-fifths of banking assets in Pakistan, showing an inordinate concentration of wealth. Today too we can identify as many families who control a high proportion of national wealth.

Concentration of wealth is not unique to Pakistan: this happens globally, especially in the developing world. Trouble is that five decades after Dr Haq’s identification, it’s many of the same families who control the wealth.

A successful economy keeps giving rise to new entrepreneurs, representing newly emerging industries and technologies, becoming its richest people. But not here in Pakistan where wealth, power and opportunities are strictly limited to an unchanging elite.

Look at the top businessmen in America like Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, etc, none of whom owe their position to family wealth. The richest people of the earlier eras — the Carnegies, Rockefellers — don’t still dominate commerce. Among recent former US presidents, Ronald Reagan’s father was a salesman, Bill Clinton’s father was an alcoholic and Barack Obama was raised by a single mother. Here almost every successful Pakistani owes his success to his father’s position.

In Pakistan, doctors’ children go on to become doctors, lawyers’ children become lawyers, ulema’s children become ulema, etc. Even singers have gharanas. There are business, political, army and bureaucrat families where several generations have produced seths, politicians, generals and high-ranking officers. In such a society, a driver’s son is constrained to become a driver, a jamadaar’s son is destined to become a jamadaar, and a maid’s daughter ends up becoming a maid.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on November 11, 2022 at 5:45pm

-

The ‘One Per Cent Republic’

Miftah Ismail Published November 10, 2022

https://www.dawn.com/news/1720082

Top corporate and other professionals only come from the urban English-educated elites, especially from the two schools I mentioned above. The only influential professions where non-elites can enter —bureaucracy and the military — are also set up such that once their people enter the highest echelons, their lifestyle, like their elite peers from other fields, becomes similar to the colonial-era gora sahibs, materially removed from the lives of the brown masses composed of batmen, naib qasids and maids.

Political power too is concentrated not in parties but in personalities. Except for one religio-political party, there isn’t a party where the head is ever replaced. Politics is based on personalities down to the local level, where politicians come from families of ‘electables’, where fathers and grandfathers were previously elected.

Is it any wonder why Pakistanis don’t win Nobel Prizes? We properly educate less than 1pc of our kids. Of course, we have smart, talented people. But most of our brilliant kids never finish school and end up working as maids and dhobis and not as physicists and economists they could’ve been. Pakistan is a graveyard for the talent and aspirations of our people.

According to Unicef, 40pc of Pakistani children under the age of five are stunted (indicating persistent undernutrition); another 18pc are wasted (indicating recent severe weight loss due to undernutrition) and 28pc are underweight. This means 86pc of our kids go to sleep hungry most nights and have the highest likelihood in South Asia of dying before their fifth birthday. This is our reality.

Pakistan works superbly for members of social and golf clubs. But it doesn’t work if you’re a hungry child, landless hari, a madressah student, a daily-wager father or an ayah raising other people’s children. Pakistan doesn’t work well for most of our middle-class families. This is why disaffection prevails and centrifugal forces find traction.

The real predictor of success is a person’s father’s status. Intelligence, ability and work ethic are not relevant. Of course, some manage to become part of the elite: but those are the exceptions that prove the rule.

Pakistan’s elite compact allows wealth and power to perpetuate over generations and keeps everyone else out. This is what’s keeping Pakistanis poor and why it’s necessary to unravel the elite compact. We need a new social contract to unite and progress as a nation.

Comment

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Indian Military Begins to Accept Its Losses in "Operation Sindoor" Against Pakistan

The Indian military leadership is finally beginning to slowly accept its losses in its unprovoked attack on Pakistan that it called "Operation Sindoor". It began with the May 31 Bloomberg interview of the Indian Chief of Defense Staff General Anil Chauhan in Singapore where he admitted losing Indian fighter aircraft to Pakistan in an aerial battle on May 7, 2025. General Chauhan further revealed that the Indian Air Force was grounded for two days after this loss. …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on July 5, 2025 at 10:30am

Trump Administration Seeks Pakistan's Help For Promoting “Durable Peace Between Israel and Iran”

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio called Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif to discuss promoting “a durable peace between Israel and Iran,” the State Department said in a statement, according to Reuters. Both leaders "agreed to continue working together to strengthen Pakistan-US relations, particularly to increase trade", said a statement released by the Pakistan government.…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on June 27, 2025 at 8:30pm — 5 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network