PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

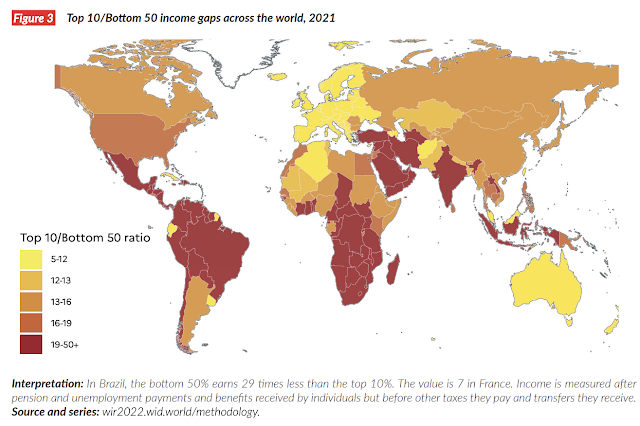

India Is Among The World's Most Unequal Countries

India is one of the most unequal countries in the world, according to the World Inequality Report 2022. There is rising poverty and hunger. Nearly 230 million middle class Indians have slipped below the poverty line, constituting a 15 to 20% increase in poverty. India ranks 94th among 107 nations ranked by World Hunger Index in 2020. Other South Asians have fared better: Pakistan (88), Nepal (73), Bangladesh (75), Sri Lanka (64) and Myanmar (78) – and only Afghanistan has fared worse at 99th place. Meanwhile, the wealth of Indian billionaires jumped by 35% during the pandemic.

|

| Income Inequality Map. Source: World Inequality Report 2022 |

Unemployment Crisis:

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and 3.5 million entrepreneurs in November alone. Many among the unemployed can no longer afford to buy food, causing a significant spike in hunger. The country's economy is finding it hard to recover from COVID waves and lockdowns, according to data from multiple sources. At the same time, the Indian government has reported an 8.4% jump in economic growth in the July-to-September period compared with a contraction of 7.4% for the same period a year earlier.

|

| Income Inequality By Regions. Source: World Inequality Report 2022 |

|

| Income & Wealth Inequality. Source: World Inequality Report 2022 |

Rising Poverty:

Nearly 230 million middle class Indians have slipped below the poverty line, constituting a 15 to 20% increase in poverty since Covid-19 struck last year, according to Pew Research. Middle class consumption has been a key driver of economic growth in India. Erosion of the middle class will likely have a significant long-term impact on the country's economy. “India, at the end of the day, is a consumption story,” says Tanvee Gupta Jain, UBS chief India economist, according to Financial Times. “If you never recovered from the 2020 wave and then you go into the 2021 wave, then it’s a concern.”

Increasing Hunger:

A United Nations report on inequality in Pakistan published in April 2021 revealed that the richest 1% Pakistanis take 9% of the national income. A quick comparison with other South Asian nations shows that the 9% income share for the top 1% in Pakistan is lower than 15.8% in Bangladesh and 21.4% in India. These inequalities result mainly from a phenomenon known as "elite capture" that allows a privileged few to take away a disproportionately large slice of public resources such as public funds and land for their benefit.

|

| Income Distribution by Quintiles in Pakistan. Source: UNDP |

Elite Capture:

Elite capture, a global phenomenon, is a form of corruption. It describes how public resources are exploited by a few privileged individuals and groups to the detriment of the larger population.

A recently published report by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has found that the elite capture in Pakistan adds up to an estimated $17.4 billion - roughly 6% of the country's economy.

Pakistan's most privileged groups include the corporate sector, feudal landlords, politicians and the military. The UN Development Program's NHDR for Pakistan, released last week, focused on issues of inequality in the country of 220 million people.

Ms. Kanni Wignaraja, assistant secretary-general and regional chief of the UNDP, told Aljazeera that Pakistani leaders have taken the findings of the report “right on” and pledged to focus on prescriptive action. “My hope is that there is strong intent to review things like the current tax and subsidy policies, to look at land and capital access", she added.

| Inequality in Pakistan. Source: UNDP |

Income Inequality:

The richest 1% of Pakistanis take 9% of the national income, according to the UNDP report titled "The three Ps of inequality: Power, People, and Policy". It was released on April 6, 2021. Comparison of income inequality in South Asia reveals that the richest 1% in Bangladesh and India claim 15.8% and 21.4% of national income respectively.

In addition to income inequality, the UNDP report describes the inequality of opportunity in terms of access to services, work with dignity and accessibility. It is based on exhaustive statistical analysis at national and provincial levels, and includes new inequality indices for child development, youth, labor and gender. Qualitative research, through focus groups with marginalized communities, has also been undertaken, and the NHDR 2020 Inequality Perception Survey conducted. The NHDR 2020 has been guided by a diverse panel of Advisory Council members, including policy makers, development practitioners, academics, and UN representatives.

Summary:

Neoliberal policies in emerging markets like India have spurred economic growth in last few decades. However, the gains from this rapid growth have been heavily skewed in favor of the rich. The rich have gotten richer while the poor have languished. The average per capita income in India has tripled in recent decades but the minimum dietary intake has fallen. According to the World Food Program, a quarter of the world's undernourished people live in India. The COVID19 pandemic has further widened the gap between the rich and poor.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid1...

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Cou...

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan's Sehat Card Health Insurance Program

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade De...

India's Unemployment and Hunger Crises"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 24, 2021 at 8:35am

-

Faseeh Mangi

@FaseehMangi

Pakistan's subsidized house finance scheme data

-260b rupees ($1.5 billion) requested by people

-109b rupees ($600 million) approved for small houses

- 32b rupees disbursedhttps://twitter.com/FaseehMangi/status/1474358251068313601?s=20

-------------------

Prime Minister Imran Khan on Wednesday formally launched the Naya Pakistan Card initiative, bringing mega welfare programmes of the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) government covering health, education, food and agriculture sectors under one umbrella.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1662707

With the launch of Naya Pakistan Card, which covers Ehsaas Ration Programme based on a food subsidy package for low-income families, Kisan Card, Sehat Card and scholarships for students, beneficiaries of various initiatives can avail all services on the same card.Addressing the ceremony held at the Governor House, Prime Minister Khan said that Kamyab Pakistan scheme was also in the pipeline under which two million eligible families would receive Rs400,000 interest-free loans for self-employment, free technical education to one member of each registered family, Rs2.7 million loan for house construction and free health insurance.

He said the proposed Kamyab Pakistan programme to be launched in the KP province would be extended to other provinces later.

Says a project promising interest-free loan for 2m eligible families is on the anvilBesides, the government was awarding 6.3m scholarships to students to encourage them to pursue higher education as Rs47bn had been allocated in this regard, he said.

In order to ensure award of scholarships on merit, a special cell was being set up at the PM secretariat to collect students’ data, he announced

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 24, 2021 at 7:09pm

-

India’s Stalled Rise

How the State Has Stifled Growth

By Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman

January/February 2022

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2021-12-14/indias-sta...

As growth slowed, other indicators of social and economic progress deteriorated. Continuing a long-term decline, female participation in the labor force reached its lowest level since Indian independence in 1948. The country’s already small manufacturing sector shrank to just 13 percent of overall GDP. After decades of improvement, progress on child health goals, such as reducing stunting, diarrhea, and acute respiratory illnesses, stalled.

And then came COVID-19, bringing with it extraordinary economic and human devastation. As the pandemic spread in 2020, the economy withered, shrinking by more than seven percent, the worst performance among major developing countries. Reversing a long-term downward trend, poverty increased substantially. And although large enterprises weathered the shock, small and medium-sized businesses were ravaged, adding to difficulties they already faced following the government’s 2016 demonetization, when 86 percent of the currency was declared invalid overnight, and the 2017 introduction of a complex goods and services tax, or GST, a value-added tax that has hit smaller companies especially hard. Perhaps the most telling statistic, for an economy with an aspiring, upwardly mobile middle class, came from the automobile industry: the number of cars sold in 2020 was the same as in 2012.

--------

Adding to a decade of stagnation, the ravages of COVID-19 have had a severe effect on Indians’ economic outlook. In June 2021, the central bank’s consumer confidence index fell to a record low, with 75 percent of those surveyed saying they believed that economic conditions had deteriorated, the worst assessment in the history of the survey.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 24, 2021 at 8:46pm

-

India’s Stalled Rise

How the State Has Stifled Growth

By Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman

January/February 2022

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2021-12-14/indias-sta...

For the Indian economy to achieve its potential, however, the government will need a sweeping new approach to policy—a reboot of the country’s software. Its industrial policy must be reoriented toward lower trade barriers and greater integration into global supply chains. The national champions strategy should be abandoned in favor of an approach that treats all firms equally. Above all, the policymaking process itself needs to be improved, so that the government can establish and maintain a stable economic environment in which manufacturing and exports can flourish.

But there is little indication that any of this will occur. More likely, as India continues to make steady improvements in its hardware—its physical and digital infrastructure, its New Welfarism—it will be held back by the defects in its software. And the software is likely to prove decisive. Unless the government can fundamentally improve its economic management and instill confidence in its policymaking process, domestic entrepreneurs and foreign firms will be reluctant to make the bold investments necessary to alter the country’s economic course.

There are further risks. The government’s growing recourse to majoritarian and illiberal policies could affect social stability and peace, as well as the integrity of institutions such as the judiciary, the media, and regulatory agencies. By undermining democratic norms and practices, such tendencies could have economic costs, too, eroding the trust of citizens and investors in the government and creating new tensions between the federal administration and the states. And India’s security challenges on both its eastern and its western border have been dramatically heightened by China’s expansionist activity in the Himalayas and the takeover of Afghanistan by the Pakistani-supported Taliban.

If these dynamics come to dominate, the Indian economy could experience another disappointing decade. Of course, there would still be modest growth, with some sectors and some segments of the population doing particularly well. But a broader boom that transforms and improves the lives of millions of Indians and convinces the world that India is back would be out of reach. In that case, the current government’s aspirations to global economic leadership may prove as elusive as those of its predecessors.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 25, 2021 at 8:41am

-

#India Facing a #Population Implosion. Urban India's fertility rate is1.6, below replacement. India has "a baby factory in the north (#Bihar, #UP, #MP, #Rajasthan) and a jobs factory in the south (#TN, #Kerala, #Andhra, #Karnataka) " @dhume https://www.wsj.com/articles/india-may-face-a-population-implosion-... via @WSJOpinion

After it gained independence in 1947, India’s soaring population—made possible by advances in medicine and disease control—seemed to doom it to poverty and hunger. Droughts in the mid-1960s raised the specter of famine. In 1966 the U.S. shipped one-fourth of its wheat output to India to avert mass starvation. Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 best-seller, “The Population Bomb,” predicted that hundreds of millions would starve and that by 1977 India could fall apart “into a large number of starving, warring minor states.”

----------

As in many countries, urbanization, rising income and female literacy, and increased contraception have led to plummeting fertility. But the biggest reason for the decline, according to Mr. Eberstadt, is hard to measure: Indian women want fewer babies.

In 1960 the average Indian woman would bear six children during her lifetime. By 2005 this had fallen to three. Urban India now has a fertility rate of 1.6, comparable to the European Union. And unlike China, whose government enforced a draconian one-child policy, India has achieved this largely without coercion. A harsh sterilization drive by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in the mid-1970s led to her crushing electoral defeat in 1977. No Indian government tried to force the matter again.

Though India may have dodged mass famine, its massive population still poses challenges. Optimists claim the country’s skew toward youth provides a demographic dividend: a large working-age cohort to support relatively few retirees.

But such sunny prognostications present only half the picture. Thanks to uneven development, in the coming decades India will house an unprecedented experiment: hundreds of millions of college graduates living among hundreds of millions of illiterates. “The education gap in India could generate an income distribution that will make Manhattan look like Sweden,” says Mr. Eberstadt.

Regional disparities complicate things further. The relatively well-educated coastal states of the south already have fertility rates well below replacement levels. Birthrates in the poor and populous Hindi heartland have fallen too, but not nearly as sharply. Three of them—Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand—remain above replacement levels.

“To oversimplify, you have a baby factory in the north and a jobs factory in the south,” says Mr. Eberstadt. “But there’s a mismatch in educational attainment between a rising cohort in the north and the needs of the economy emerging in the south.” Kerala, in the south, has a literacy rate of 96%. Bihar, in the north, is 71%.

Then there’s the most sensitive question: political representation. In the relative weight of its states, India’s Parliament has remained frozen since the 1971 census. The average parliamentarian from Uttar Pradesh represents three million people, while a counterpart from Tamil Nadu represents 1.8 million. A 2019 report by Carnegie Endowment scholars Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson calculated that if Parliament were reapportioned according to the likely population in 2026, the five southern states would send 26 fewer representatives to the 545-seat Parliament. The four most populous Hindi heartland states would add 31 seats.

If India is lucky, it will defuse these problems as successfully as it dealt with food shortages a generation ago. But though the population bomb failed to explode, it doesn’t mean India is safe from other ticking time bombs.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 25, 2021 at 12:29pm

-

Indian middle class is not growing.

Car sales in 2010 2.5 million

Car sales in 2021 2.7 million

Motorcycle sales 2010 12 million

Motorcycle sales 2021 15 million

Pakistan car sales grew from 137,000 in 2010 to 198,000 in 2021Pakistan motorcycle sales grew from 700,000 in 2010 to 2.4 million in 2021

Pakistan car sales grew from 137,000 in 2010 to 198,000 in 2021

Pakistan motorcycle sales grew from 700,000 in 2010 to 2.4 million in 2021

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 25, 2021 at 1:21pm

-

Manufacturing employment nearly half of what it was five years ago

Manufacturing accounts for nearly 17% of India's GDP, but the sector has seen employment decline sharply in last 5 years - from employing 51 million Indians in 2016-17 to reach 27.3 million in 2020-21

https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/ceda-cmie-...

With the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic battering India at present, the Indian economic outlook looks bleak for the second year in a row. In 2020-21, India’s real GDP growth is estimated to be minus 8 per cent. This would also put pressure on India’s employment numbers. In previous bulletins, we have analysed the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on employment, individual and household incomes and expenditures in 2020.

In this CEDA-CMIE Bulletin, we try to take a longer-term view of sector-wise employment in India. We base this on CMIE’s monthly time-series of employment by industry going back to the year 2016. For this bulletin, we have focused on seven sectors – agriculture, mines, manufacturing, real estate and construction, financial services, non-financial services, and public administrative services. These sectors make up for 99 per cent of total employment in the country.

In figure 2 and 3 (below), we look at four sectors. These are agriculture, financial services, non-financial services, and public administrative services. Non-financial services exclude public administrative services and defense services. Together, these accounted for 69 per cent of total employment in 2016-17 and 78 per cent in 2020-21.

The agriculture sector employed 145.6 million people in 2016-17. This increased by 4 per cent to reach 151.8 million in 2020-21. While it constituted 36 per cent of all employment in 2016-17, the figure rose to 40 per cent in 2020-21, underlining the sector’s importance for the Indian economy. Employment in agriculture has been on the rise over the last two years with year-on-year (YoY) growth rates of 1.7 per cent in 2019-20 and 4.1 per cent in 2020-21.

119.7 million Indians were employed in the non-financial services in 2016-17 (excluding those in public administrative services and defense services) (Figure 3). This number rose by 6.7 per cent to reach 127.7 million in 2020-21. The financial services sector employed 5.3 million people in 2016-17 and this grew by 9 per cent to 5.8 million in 2020-21.

Public administrative services employed 9.8 million people in 2016-17 but it decreased by 19 per cent to 7.9 million in 2020-21.

In figure 4, we look at employment in manufacturing, real estate & construction, and mining sectors. Together these sectors accounted for 30 per cent of all employment in 2016-17 which came down to 21 per cent in 2020-21.

Manufacturing accounts for nearly 17 per cent of India’s GDP but the sector has seen employment decline sharply in the last 5 years. From employing 51 million Indians in 2016-17, employment in the sector declined by 46 per cent to reach 27.3 million in 2020-21. This indicates the severity of the employment crisis in India predating the pandemic.

On a YoY basis, it employed 32 per cent fewer people in 2020-21 over 2019-20. It had seen a growth of 1 per cent (YoY) in 2019-20. This has happened despite the Indian government’s push to improve manufacturing in the country with the ‘Make in India’ project. Under the project, India sought to create an additional 100 million manufacturing jobs in India by 2022 and to increase manufacturing’s contribution to GDP to 20 per cent by 2025.

Instead of increasing employment in the sector, we have seen a sharp decline over the last 5 years. When we look closely at industries that make the manufacturing sector, we find that this is a secular decline in employment across all sub-sectors, except chemical industries.

All sub-sectors within manufacturing registered a longer-term decline.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 26, 2021 at 2:27pm

-

India has spent a decade wasting the potential of its young #population. Once considered a formidable asset, #India’s #demographic bulge turned toxic due to the country’s lost economic decade! #unemployment #Modi #BJP #Hindutva https://qz.com/india/2104191/india-has-wasted-the-potential-of-its-...

For the better part of the past decade, India was touted as the next big economic growth story after China because of its relatively younger population. “Demographic dividend”—the potential resulting from a country’s working-age population being larger than its non-working-age population—was the key phrase.Come 2022, the median age in India will be 28, well below 37 in China and the US.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 27, 2021 at 9:46am

-

The NMP is hardly the panacea for growth in India

https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-nmp-is-hardly-the-panace...

As the Government has also shown, there are out-of-the-box policy initiatives to revamp public sector businesses

The National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) envisages an aggregate monetisation potential of ₹6-lakh crore through the leasing of core assets of the Central government in sectors such as roads, railways, power, oil and gas pipelines, telecom, civil aviation, shipping ports and waterways, mining, food and public distribution, coal, housing and urban affairs, and stadiums and sports complexes, to name some sectors, over a four-year period (FY2022 to FY2025). But the point is that it only underscores the need for policy makers to investigate the key reasons and processes which led to once profit-making public sector assets becoming inefficient and sick businesses.

------------------

Congress leader Sachin Pilot on Wednesday slammed the Central government over National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) by saying that the new scheme will create monopoly and duopoly in the economy.

https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/nmp-will-...

Addressing a press conference in Bengaluru, Pilot questioned the government's decision to "lease core strategic assets of the country to private entities".

"The government said that NMP will get revenue of Rs 6 lakh crores for the next four years. The money that they will raise, will it go to fulfil the Rs 5.5 lakh crores deficit that we are running today or is it there to boost revenue," he stated.

"There is already a problem of unemployment in our country. When private entities take over the assets like railways, telecom and aviation, they will certainly lay off more people to make profits, which means more unemployment," he added.

Pilot further said that handing over important assets of the country to a handful of people will create a monopoly and duopoly in the economy.

The Congress MLA asserted that the NMP poses serious questions on the country's integrity and security. "I want to ask what stops the international funds to make an investment and take a stake in these important assets," he stated.

"There are many countries that forbid Chinese entities to bid for telecom tower or fibre optical cable. I want to question the government what safeguards have been placed in NMP to stop inappropriate entities from bidding for our core strategic assets," he added.

Pilot called the government's decision regarding NMP as 'unilateral' that happened without any discussion with trade unions, stakeholders or the Opposition. He further questioned the transparency of the whole process and how it is going to benefit people.

"Will the money raised be used to double farmers' income or to give Rs 15 lakhs to every Indian citizen as promised by the government? Or will it be used to make a building complex or in some vanity project," he questioned.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 27, 2021 at 2:28pm

-

By Abhijit Banerjee, Nobel Laureate Economist

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/23/opinion/culture/holiday-feasting...

There’s a long tradition among social thinkers and policymakers of treating workers as walking, talking machines that turn calories into work and work into commodities that get sold on the market. Under capitalism, food is important because it provides fuel to the work force. In this line of thinking, enjoyment of food is at best a distraction and often a dangerous invitation to indolence.

The scolding American lawmakers who want to forbid the use of food stamps to purchase junk food are part of a long lineage that goes back to the Victorian workhouses, which made sure that the food was never inviting enough to encourage sloth. It is the continuing obsession with treating working-class people as efficient machines for turning nutrients into output that explains why so many governments insist on giving bags of grain to the poor instead of money that they might waste. This infantilizes the poor and, except in very special circumstances, it does nothing to improve nutrition.

The pleasure of eating, to say nothing of cooking, has no place in this narrative. And the idea that if working people knew what was good for them, they’d simply seek out more food as fuel is a woefully limited view of the eating experience of most of the world. As anybody who has been poor or has spent time with poor people knows, eating something special is a source of great excitement.

As it is for everyone. Standing at the end of this very dark and disappointing year, almost two years into a pandemic, we all need the joy of a feast — whether actual or metaphorical.

Every village has its feast days and its special festal foods. Somewhere goats will be slaughtered, somewhere ceremonial coconuts cracked. Perhaps fresh dates will be piled on special plates that come out once a year. Maybe mothers will pop sweetened balls of rice into the mouths of their children.

Friends and relatives will come over to help roast an entire camel for Eid; to share scoops of feijoada, that wonderful Brazilian stew of beans simmered with off-cuts, from pig’s ears to cow’s tongue; to pinch the dumplings for the Lunar New Year; to fold the delicate edges of sweet coconut-stuffed Maharashtrian karanji, to be fried under the watchful eye of the matriarch. The feast’s inspiration might be religious, but it could as well be a wedding, a birth, a funeral or a harvest.

-------

This feasting season, that momentary joy is likely to feel especially essential. Most of us have had reasons to worry — about ourselves, about our children and parents, about where the world is headed. This year many lost friends and relatives, jobs and businesses. Many spent months working in Zoom-land, languishing even as they counted themselves lucky to be employed.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 28, 2021 at 7:31am

-

#India #Unemployment: Modi gov't said in December that 9% of all MSMEs had shut down because of #COVID19. In May, another survey of over 6,000 MSMEs and startups found that 59% were planning to shut shop, scale down or sell before the end of 2021. #economy https://aje.io/ytyan4

Baldev Kumar threw his head back and laughed at the mention of India’s resurgent GDP growth. The country’s economy clocked an 8.4-percent uptick between July and September compared with the same period last year. India’s Home Minister Amit Shah has boasted that the country might emerge as the world’s fastest-growing economy in 2022.

Kumar could not care less.

As far as he was concerned, the crumpled receipt in his hand told a different story: The tomatoes, onions and okra he had just bought cost nearly twice as much as they did in early November. The 47-year-old mechanic had lost his job at the start of the pandemic. The auto parts store he then joined shut shop earlier this year. Now working at a car showroom in the Bengaluru neighbourhood of Domlur, he is worried he might soon be laid off as auto sales remain low across India.

He has put plans for his daughter’s wedding on hold, unsure whether he can foot the bill. He used to take a bus to work. Now he walks the five-kilometre (three-mile) distance to save a few rupees. “I don’t know which India that’s in,” he said, referring to the GDP figures. “The India I live in is struggling.”

Kumar wasn’t exaggerating – even if Shah’s prognosis turns out to be correct.

Asia’s third-largest economy is indeed growing again, and faster than most major nations. Its stock market indices, such as the Sensex and Nifty, are at levels that are significantly higher than at the start of 2021 – despite a stumble in recent weeks. But many economists are warning that these indicators, while welcome, mask a worrying challenge – some describe it as a crisis – that India confronts as it enters 2022.

November saw inflation rise by 14.23 percent, building on a pattern of double-digit increases that have hit India for several months now. Fuel and energy prices rose nearly 40 percent last month. Urban unemployment – most of the better-paying jobs are in cities – has been moving up since September and is now above 9 percent, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, an independent think-tank. “Inflation hits the poor the most,” said Jayati Ghosh, a leading development economist at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

All of this is impacting demand: Government data shows that private consumption between April and September of 2021 was 7.7 percent lower than in 2019-2020. The economic recovery from the pandemic has so far been driven by demand from well-to-do sections of Indian society, said Sabyasachi Kar, who holds the RBI Chair at the Institute of Economic Growth. “The real challenge will start in 2022,” he told Al Jazeera. “We’ll need demand from poorer sections of society to also pick up in order to sustain growth.”

-------------

“The decimation of MSMEs is why we’re seeing core inflation, and we should be very worried,” said economist Pronab Sen, former chief statistician of India, referring to an inflation measure that leaves out food and energy because of their volatile price shifts. India’s core inflation stood at more than 6 percent in October. The level of competition in the market has also dramatically shrunk, he said. “Pricing power has shifted to a small number of large companies,” Sen told Al Jazeera. “And it is their exercise of this power that is leading to core inflation.”

When fuel prices rise globally – and subsequently in India – some inflation is unavoidable. But a competitive market usually forces companies to absorb much of that burden in their margins. Without that competition, Sen said, it is easier for firms to pass more of the increased costs on to consumers.

MSMEs have long been the backbone of the Indian labour market, employing 110 million people. Their struggles are a key reason for India’s failure to reduce unemployment rates, Sen added.

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Clean Energy Revolution: Soaring Solar Energy Battery Storage in Pakistan

Pakistan imported an estimated 1.25 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of lithium-ion battery packs in 2024 and another 400 megawatt-hours (MWh) in the first two months of 2025, according to a research report by the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). The report projects these imports to reach 8.75 gigawatt-hours (GWh) by 2030. Using …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on June 14, 2025 at 10:30am

Builder.AI: Yet Another Global Indian Scam?

A London-based startup builder.ai, founded by an Indian named Sachin Dev Duggal, recently filed for bankruptcy after its ‘neural network’ was discovered to be 700 Indians coding in India. The company promoted its "code-building AI" to be as easy as "ordering pizza". It was backed by nearly half a billion dollar investment by top tech investors including Microsoft. The company was valued at $1.5 billion. This is the latest among a series of global scams originating in India. …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on June 8, 2025 at 4:30pm — 9 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network