PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and 3.5 million entrepreneurs in November alone. Many among the unemployed can no longer afford to buy food, causing a significant spike in hunger. The country's economy is finding it hard to recover from COVID waves and lockdowns, according to data from multiple sources. At the same time, the Indian government has reported an 8.4% jump in economic growth in the July-to-September period compared with a contraction of 7.4% for the same period a year earlier. This raises the following questions: Has India had jobless growth? Or its GDP figures are fudged? If the Indian economy fails to deliver for the common man, will Prime Minister Narendra Modi step up his anti-Pakistan and anti-Muslim rhetoric to maintain his popularity among Hindus?

|

| Labor Participation Rate in India. Source: CMIE |

Unemployment Crisis:

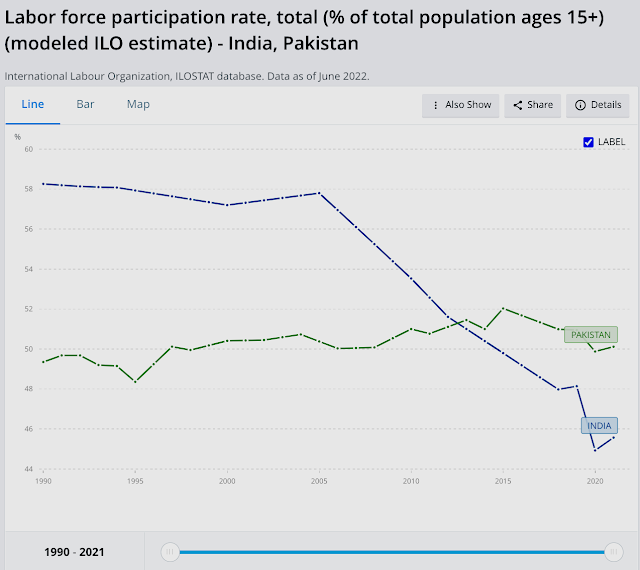

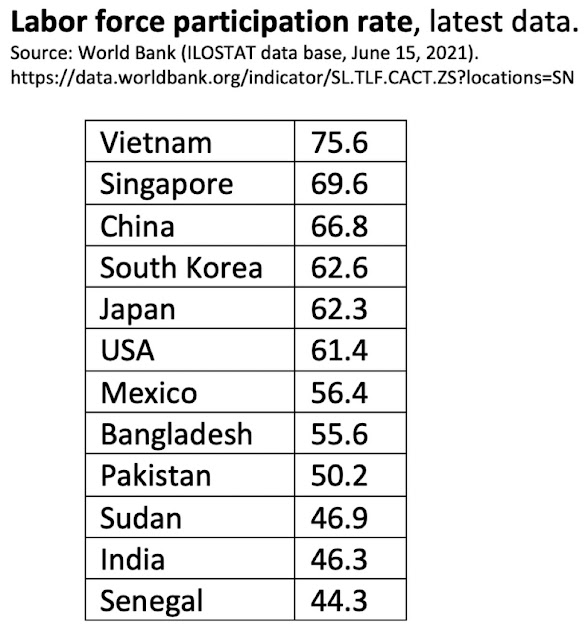

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and its labor participation rate (LPR) slipped from 40.41% to 40.15% in November, 2021, according to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). In addition to the loss of salaried jobs, the number of entrepreneurs in India declined by 3.5 million. India's labor participation rate of 40.15% is lower than Pakistan's 48%. Here's an except of the latest CMIE report:

"India’s LPR is much lower than global levels. According to the World Bank, the modelled ILO estimate for the world in 2020 was 58.6 per cent (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.ZS). The same model places India’s LPR at 46 per cent. India is a large country and its low LPR drags down the world LPR as well. Implicitly, most other countries have a much higher LPR than the world average. According to the World Bank’s modelled ILO estimates, there are only 17 countries worse than India on LPR. Most of these are middle-eastern countries. These are countries such as Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Syria, Senegal and Lebanon. Some of these countries are oil-rich and others are unfortunately mired in civil strife. India neither has the privileges of oil-rich countries nor the civil disturbances that could keep the LPR low. Yet, it suffers an LPR that is as low as seen in these countries".

|

| Labor Participation Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: World Bank/ILO |

|

| Labor Participation Rates for Selected Nations. Source: World Bank/ILO |

Youth unemployment for ages15-24 in India is 24.9%, the highest in South Asia region. It is 14.8% in Bangladesh 14.8% and 9.2% in Pakistan, according to the International Labor Organization and the World Bank.

|

| Youth Unemployment in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Source: ILO, WB |

In spite of the headline GDP growth figures highlighted by the Indian and world media, the fact is that it has been jobless growth. The labor participation rate (LPR) in India has been falling for more than a decade. The LPR in India has been below Pakistan's for several years, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

|

| Indian GDP Sectoral Contribution Trend. Source: Ashoka Mody |

|

| Indian Employment Trends By Sector. Source: CMIE Via Business Standard |

|

| World Hunger Rankings 2020. Source: World Hunger Index Report |

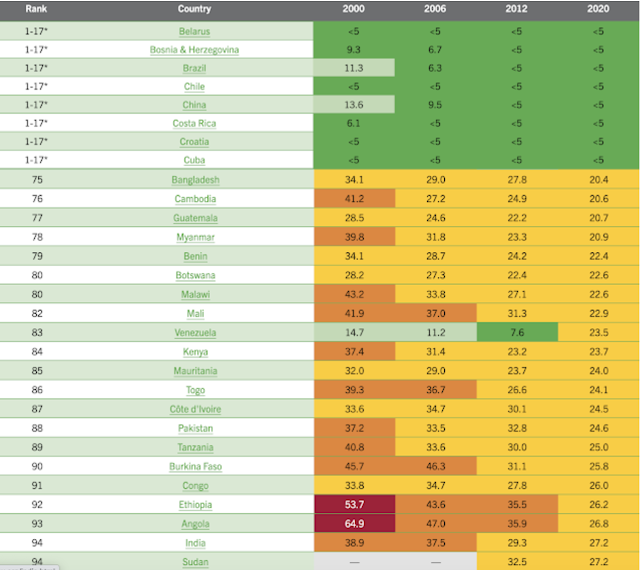

Hunger and malnutrition are worsening in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia because of the coronavirus pandemic, especially in low-income communities or those already stricken by continued conflict.

India has performed particularly poorly because of one of the world's strictest lockdowns imposed by Prime Minister Modi to contain the spread of the virus.

Hanke Annual Misery Index:

Pakistan's Real GDP:

Vehicles and home appliance ownership data analyzed by Dr. Jawaid Abdul Ghani of Karachi School of Business Leadership suggests that the officially reported GDP significantly understates Pakistan's actual GDP. Indeed, many economists believe that Pakistan’s economy is at least double the size that is officially reported in the government's Economic Surveys. The GDP has not been rebased in more than a decade. It was last rebased in 2005-6 while India’s was rebased in 2011 and Bangladesh’s in 2013. Just rebasing the Pakistani economy will result in at least 50% increase in official GDP. A research paper by economists Ali Kemal and Ahmad Waqar Qasim of PIDE (Pakistan Institute of Development Economics) estimated in 2012 that the Pakistani economy’s size then was around $400 billion. All they did was look at the consumption data to reach their conclusion. They used the data reported in regular PSLM (Pakistan Social and Living Standard Measurements) surveys on actual living standards. They found that a huge chunk of the country's economy is undocumented.

Pakistan's service sector which contributes more than 50% of the country's GDP is mostly cash-based and least documented. There is a lot of currency in circulation. According to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the currency in circulation has increased to Rs. 7.4 trillion by the end of the financial year 2020-21, up from Rs 6.7 trillion in the last financial year, a double-digit growth of 10.4% year-on-year. Currency in circulation (CIC), as percent of M2 money supply and currency-to-deposit ratio, has been increasing over the last few years. The CIC/M2 ratio is now close to 30%. The average CIC/M2 ratio in FY18-21 was measured at 28%, up from 22% in FY10-15. This 1.2 trillion rupee increase could have generated undocumented GDP of Rs 3.1 trillion at the historic velocity of 2.6, according to a report in The Business Recorder. In comparison to Bangladesh (CIC/M2 at 13%), Pakistan’s cash economy is double the size. Even a casual observer can see that the living standards in Pakistan are higher than those in Bangladesh and India.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Counterparts

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade Deficits

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Riaz Haq

#India #Electricity Crisis Worst Since Oct 2021: Many northern states suffered hours-long power outages in October, when a crippling #coal shortage caused the worst electricity deficit in nearly five years. #EnergyCrisis #BJP #Modi #economy #unemployment https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/indias-march-electricity-...

The western state of Gujarat, one of the country's most industrialized, has ordered a staggered shutdown of "non-continuous process" industries in key cities next week, according to a government note reviewed by Reuters.

India's electricity shortage from March 1 to March 30 was its worst since October, a Reuters analysis of government data shows.

A surge in power demand in March has forced India to cut coal supplies to the non-power sector and put on hold plans for some fuel auctions for utilities without supply deals due to a slump in inventories.

Many northern states suffered hours-long power outages in October, when a crippling coal shortage caused the worst electricity deficit in nearly five years.

Shortages in the eastern state of Jharkhand and Uttarakhand in the north surpassed those of October, the latest data showed.

The western state of Gujarat, one of the country's most industrialised, has ordered a staggered shutdown of "non-continuous process" industries in key cities next week, according to a government note reviewed by Reuters.

A Gujarat energy department official said the move was due to power shortages and to facilitate continuous power supply to farmers, adding a similar strategy was last used in 2010. He declined to comment on how long the staggered shutdown will be in place.

The official declined to be named as he was not authorised to speak to the media.

The southern state of Andhra Pradesh and the tourist resort state of Goa, which registered marginal shortages in October, suffered deficits several times larger in March.

The deficit in March was 574 million kilowatt-hours, a measure that multiplies power level by duration, a Reuters analysis of data from federal grid regulator POSOCO showed.

That amounted to 0.5% of overall demand for the period, or half the deficit of 1% in October.

The northern states of Haryana, Rajasthan and Punjab and the eastern state of Bihar, some parts of which suffered widespread outages in October, accounted for most of the deficit in March, but shortfalls were lower, the data showed.

Mar 31, 2022

Riaz Haq

#India more than doubles price of locally produced #gas.The price of gas from regulated fields of state-owned ONGC and Oil India Ltd will rise to a record $6.10 per million British thermal unit from the current $2.90. #Energy #Economy #BJP #Modi https://www.livemint.com/industry/energy/india-more-than-doubles-do...

The Central Government on Thursday more than doubled the price of domestically produced natural gas for the six months beginning tomorrow (1 April), reflecting a surge in global prices.

The Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell of the federal oil ministry announced the new prices today.

This will raise the prices of gas sold to households, the power sector, industries and fertiliser firms, adding to overall inflation.

As per a notification issued by the oil ministry's PPAC, the price of gas from regulated fields of state-owned Oil and Natural Gas Corp Ltd and Oil India Ltd will rise to a record $6.10 per million British thermal unit from the current $2.90.

The rate paid for difficult fields like deepwater will rise to $9.92 for April-September from $6.13 per mmBtu, the notification stated.

India links prices of locally produced gas from old fields to a formula tied to global benchmarks, including Henry Hub, Alberta gas, NBP and Russian gas.

High natural gas prices will boost earnings of producer ONGC, Oil India Ltd and Reliance Industries.

India's annual retail inflation exceeded 6% for the second consecutive month in February.

Mar 31, 2022

Riaz Haq

India's jobless rate falls to 7.6% in March from 8.1% a month earlier: CMIE

Unemployment rate in the country is decreasing with the economy slowly returning to normal, according to CMIE data.

https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/india-s-u...

Haryana's unemployment rate the highest in India, shows analysis

India's unemployment rate falls to 6.57%, lowest since March 2021: CMIE

Households have not recovered

Employment and the government

Unemployment falls in UP, on the rise in Punjab and Goa, shows data

Unemployment rate in the country is decreasing with the economy slowly returning to normal, according to CMIE data.

The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy's monthly time series data revealed that the overall unemployment rate in India was 8.10 per cent in February 2022, which fell to 7.6 per cent in March.

On April 2, the ratio further dropped to 7.5 per cent, with urban unemployment rate at 8.5 per cent and rural at 7.1 per cent.

Retired professor of economics at Indian Statistical Institute Abhirup Sarkar said that though the overall unemployment rate is falling, it is still high for a "poor" country like India.

The decrease in the ratio shows that the economy is getting back on track after being hit by COVID-19 for two years, he said.

"But still, this unemployment rate is high for India which is a poor country. Poor people, particularly in rural areas, cannot afford to remain unemployed, for which they are taking up any job which comes in their way," Sarkar said.

According to the data, Haryana recorded the highest unemployment rate in March at 26.7 per cent, followed by Rajasthan and Jammu and Kashmir at 25 per cent each, Bihar at 14.4 per cent, Tripura at 14.1 per cent and West Bengal at 5.6 per cent.

In April 2021, the overall unemployment rate was 7.97 per cent and shot up to 11.84 per cent in May last year.

Karnataka and Gujarat registered the least unemployment rate at 1.8.per cent each in March, 2022.

Apr 3, 2022

Riaz Haq

India's labour force shrinks by 3.8 million in March, lowest in eight months

SECTIONSIndia's labour force shrinks by 3.8 million in March, lowest in eight monthsBy Yogima Seth Sharma, ET BureauLast Updated: Apr 14, 2022, 06:18 PM IST

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/jobs/indias-labour-force-shrin...

India’s labour force shrunk by 3.8 million during March 2022 to 428 million, the lowest in eight months since July 2021 with both employment and unemployment falling last month which is the biggest sign of economic distress, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy said.

According to CMIE, employment shrunk by 1.4 million to 396 million in March 2022 while the count of the unemployed fell by 2.4 million in March 2022. This resulted in a decline in the employment rate from 36.7% in February 2022 to 36.5% in March while the unemployment rate fell to 7.6% from 8.1% in February.

Apr 15, 2022

Riaz Haq

The unemployment rate fell in March 2022 to 7.6 per cent from 8.1 per cent in February. The good news on the labour markets front in March 2022 stops here. All the other data point to worsening labour market conditions in March 2022.

https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2022041...

The labour participation rate (LPR) fell to 39.5 per cent in March 2022. This was lower than the 39.9 per cent participation rate recorded in February. It is also lower than during the second wave of Covid-19 in April-June 2021. The lowest the labour participation rate had fallen to in the second wave was in June 2021 when it fell to 39.6 per cent. The average LPR during April-June 2021 was 40 per cent. March 2022, with no Covid-19 wave and with much lesser restrictions on mobility, has reported a worse LPR of 39.5 per cent.

The labour force shrunk by 3.8 million during March 2022 to 428 million. This is the lowest labour force in eight months, i.e. since July 2021. Employment shrunk by 1.4 million to 396 million in March 2022, which was the lowest level since June 2021. The count of the unemployed fell by 2.4 million in March 2022. This is what caused the fall in the unemployment rate. But, the fall in the absolute count of unemployed or the unemployment rate is not because more people got employed. We have already noted that employment actually fell in March, by a substantial 1.4 million.

What the labour market statistics of March 2022 show is India’s biggest sign of economic distress. Millions left the labour markets they stopped even looking for employment, possibly too disappointed with their failure to get a job and under the belief that there were no jobs available.

This is not the first time that India has seen a fall in the labour force in a month wherein both its constituents the employed and the unemployed have fallen simultaneously. Some of this phenomenon occurring during a month could be a reflection of short-term labour market variations, or even sampling variations. What stands out this time is that the labour force and both its constituents shrunk during a larger period of the quarter of March 2022. This is for the first time in over three years, i.e. since the quarter of June 2018 that we have seen such a decline in the labour force.

The decline in the LPR reflects the inadequacy of the growth in employment opportunities. This is because LPR compares the labour force with the working age population. The working age population continues to grow and if job opportunities do not grow in tandem, then the LPR falls. But, a decline in the labour force in absolute terms reflects a shrinkage in employment opportunities in absolute terms.

The matter gets worse when we dwell into the source of fall in employment.The composition of the 1.4 million fall in employment in March 2022 reveals a much bigger problem on the employment front. Non-agricultural jobs fell by a whopping 16.7 million. This was offset by a 15.3 million increase in employment in agriculture. Such a large increase in employment in agriculture is likely a seasonal demand for workers preparing for the rabi harvest. But, March is a tad too early for the rabi harvest. It is possible that a significant portion of the increase in employment in agriculture in March was disguised unemployment.

The fall in non-agricultural jobs in March is large and therefore worrisome.

Industrial jobs fell by 7.6 million in March 2022. The manufacturing sector shed 4.1 million jobs, the construction sector shed 2.9 million and mines shed 1.1 million jobs. Utilities saw a small increase. Manufacturing industries that reported a fall in jobs were the large organised sectors cement and metals.

The fall in manufacturing jobs is surprising. After a disastrous 2020-21, manufacturing jobs had been recovering through most of 2021-22. Except in July 2021 when employment in manufacturing was lower than it was in the year ago month, and that was by a whisker, employment in all other months till February 2022 was higher than in the corresponding year ago month. March was expected to maintain the momentum. The fall in March 2022 is therefore surprising. The March 2022 employment was a 12.5 per cent fall over February (which had lesser days) and it was a 4.3 per cent fall over March 2021, which was on the eve of the second wave of Covid-19. The fall in March is also surprising because traditionally March was seasonally a far busier month than other months of the year.

The construction sector has recovered from the lockdown shocks. But, it has stagnated at employing about 64 million. It is unable to get back to its 68-72 million levels of employment in 2018. In March 2022, employment in the construction industry was down to less than 62 million. Employment in retail trade is comparable to construction. The trade employed a record 70 million in February 2022. This fell to 65.6 million in March.

The 1.4 million fall in employment in March translates into a fall in the employment rate as well. The employment rate, or the proportion of the working-age population that is employed, is the most important labour market indicator. The employment rate fell from 36.7 per cent in February 2022 to 36.5 per cent in March.

Data for March 2022 has revealed once again that the unemployment rate is an unreliable indicator of economic conditions.

Apr 15, 2022

Riaz Haq

RSS stresses on 'Bharat-centric' job models to tackle unemployment

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has called for "Bharat-centric" models of employment generation to strengthen the economy and achieve sustainable and holistic development

https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/rss-stres...

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has called for "Bharat-centric" models of employment generation to strengthen the economy and achieve sustainable and holistic development.

In the wake of several youth in the country facing unemployment, the Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha (ABPS), the top decision-making body of the RSS, passed a resolution on Sunday to promote work opportunities to make the country self-reliant.

In the resolution, the ABPS said it wishes to emphasise that the entire society has to play a proactive role in harnessing work opportunities to mitigate the overall employment challenge.

"As we have experienced the impact of the recent COVID-19 pandemic on employment and livelihood, we have also witnessed opening up of new opportunities of which some sections of the society have taken benefit," it said.

The ABPS is of the opinion that thrust is to be given to "Bharatiya economic model" that is human-centric, labour intensive, eco-friendly and lays stress on decentralisation and equitable distribution of benefits and augments village economy, micro scale, small scale and agro-based industries, the resolution said.

"The ABPS calls upon citizens to work on Bharat-centric models of employment generation to strengthen the economy and achieve sustainable and holistic development," it said.

The three-day meeting of the ABPS concluded at Pirana on the outskirts of Ahmedabad on Sunday.

According to the resolution, the areas like rural employability, unorganised sector employment, jobs to women and their overall participation in the economy need to be boosted. Efforts are essential to adapt new technologies and soft skills appropriate to the societal conditions, it said.

"Our manufacturing sector, that has high employment potential, requires to be bolstered, which can also lessen our dependence on imports," it said.

The resolution also said that an environment conducive of encouraging entrepreneurship should be created by educating and counselling people, especially youth, so that they can come out of the mentality of seeking jobs only.

Similar entrepreneurial spirit also needs to be fostered among women, village folk and people from remote and tribal areas, it said.

"The ABPS feels that we, as a society, look for innovative ways to address the challenges of fast changing global economic and technological scenario. Opportunities of employment and entrepreneurship with emerging digital economy and export possibilities should be keenly explored," the RSS resolution said.

"We should engage ourselves in manpower training both pre and on job, research and technology innovations, motivation for start ups and green technology ventures," it said.

Apr 15, 2022

Riaz Haq

Medium Small and Micro Enterprises (SMEs) have always been the backbone of an economy in general and secondary sector in particular. For a capital scarce developing country like India, SMEs are considered as panacea for several economic woes like unemployment, poverty, income inequalities and regional imbalances.

https://www.mbarendezvous.com/more/msme-indian-economy/

The MSME Development act classifies manufacturing units into medium, small and micro enterprises depending upon the investment made in plant and machinery. Any enterprise with investment in plant and machinery of up to INR 50 million is considered as medium enterprise while those having investment between INR1.0 million to INR2.5 million is a small enterprise and one with less than INR1.0 million is a micro enterprise. In service sector, any enterprise with the investment limit of INR1.0 million, between INR 1.0-20 million and of upto INR 50 million is called as micro, small and medium enterprise respectively.

The MSMEs have played a great role in ensuring the socialistic goals like equality of income and balance regional development as envisaged by the planners soon after the independence. With the meagre investment in comparison to the various large scale private and public enterprises, the MSMEs are found to be more efficient providing more employment opportunities at relatively lower cost. The employment intensity of MSMEs is estimated to be four times greater than that of large enterprises. Currently, around 36 million SMEs are generating 80 million employment opportunities, contributing 8% of the GDP, 45% of total manufacturing output and 40% of the total exports from the country. MSMEs account for more than 80% of the total industrial enterprises in India creating more than 8000 value added products.

The most important contribution of SMEs in India is promoting the balanced economic development. The trickle down effects of large enterprises is very limited in contrast to small industries where fruits of percolation of economic growth are more visible. While the large enterprises largely created the islands of prosperity in the ocean of poverty, small enterprises have succeeded in fulfilling the socialistic goals of providing equitable growth. It had also helped in industrialization of rural and backward areas, thereby, reducing regional imbalances, assuring more equitable distribution of national income.Urban area with around 857,000 enterprises accounted for 54.77% of the total working enterprises in Registered MSME sector whereas in rural areas around 707,000 enterprises (45.23% of the working enterprises) are located. Small industries also help the large in industries by supplying them ancillary products.

Apr 17, 2022

Riaz Haq

#India Is Stalling the #WHO's Efforts to Make Global #Covid #Death Toll Public. Over a third of the additional 9 million deaths are estimated to have occurred in India, where the government of PM #Modi has stood by its own count of about 520,000. #BJP

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/16/health/global-covid-deaths-who-i...

An ambitious effort by the World Health Organization to calculate the global death toll from the coronavirus pandemic has found that vastly more people died than previously believed — a total of about 15 million by the end of 2021, more than double the official total of six million reported by countries individually.

But the release of the staggering estimate — the result of more than a year of research and analysis by experts around the world and the most comprehensive look at the lethality of the pandemic to date — has been delayed for months because of objections from India, which disputes the calculation of how many of its citizens died and has tried to keep it from becoming public.

More than a third of the additional nine million deaths are estimated to have occurred in India, where the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has stood by its own count of about 520,000. The W.H.O. will show the country’s toll is at least four million, according to people familiar with the numbers who were not authorized to disclose them, which would give India the highest tally in the world, they said. The Times was unable to learn the estimates for other countries.

The W.H.O. calculation combined national data on reported deaths with new information from localities and household surveys, and with statistical models that aim to account for deaths that were missed. Most of the difference in the new global estimate represents previously uncounted deaths, the bulk of which were directly from Covid; the new number also includes indirect deaths, like those of people unable to access care for other ailments because of the pandemic.

The delay in releasing the figures is significant because the global data is essential for understanding how the pandemic has played out and what steps could mitigate a similar crisis in the future. It has created turmoil in the normally staid world of health statistics — a feud cloaked in anodyne language is playing out at the United Nations Statistical Commission, the world body that gathers health data, spurred by India’s refusal to cooperate.

“It’s important for global accounting and the moral obligation to those who have died, but also important very practically. If there are subsequent waves, then really understanding the death total is key to knowing if vaccination campaigns are working,” said Dr. Prabhat Jha, director of the Centre for Global Health Research in Toronto and a member of the expert working group supporting the W.H.O.’s excess death calculation. “And it’s important for accountability.”

To try to take the true measure of the pandemic’s impact, the W.H.O. assembled a collection of specialists including demographers, public health experts, statisticians and data scientists. The Technical Advisory Group, as it is known, has been collaborating across countries to try to piece together the most complete accounting of the pandemic dead.

The Times spoke with more than 10 people familiar with the data. The W.H.O. had planned to make the numbers public in January but the release has continually been pushed back.

Recently, a few members of the group warned the W.H.O. that if the organization did not release the figures, the experts would do so themselves, three people familiar with the matter said.

Apr 17, 2022

Riaz Haq

Bulk of India’s unemployed population is in the middle-income households that earn between Rs 2 lakh and Rs 5 lakh a year despite the fact that they have the highest labour participation rate among non-rich household groups, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy said.

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/jobs/middle-income-households-...

Citing its Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS) data, CMIE said the middle class households accounted for half of the total households and also half of the unemployed and the largest number of unemployed people while the average labour participation rate (LPR) of this group was 43% compared to the overall average LPR was 40.8%. Also, it experiences an elevated unemployment rate of over 9%.

“India’s biggest challenge on the employment front is to provide jobs that yield about Rs 2,00,000 a year to about 16 million unemployed in the middle class households,” CMIE said in its weekly labour market analysis.

CMIE has divided households into five income classes. At the bottom of the income pyramid are households that earn less than Rs 100,000 a year. The next group earns between Rs 100,000 and Rs.200,000 a year and is called the lower middle class. The third group of households earns between Rs 200,000 and Rs 500,000 a year and belong to the middle income class. The fourth earns between Rs 500,000 and Rs 1 million a year and could be classified as the upper middle class and the richest group of house earn more than Rs 1 million in a year.

Further, a little over a third of the unemployed reside in the lower middle income households that earn between Rs 1 lakh and Rs 2 lakh. These households accounted for about 45 per cent of all households and the share of this class in the total unemployed increased from 33% during September-December 2019 to 39.5% during May-August 2021 as a significant portion of this income group migrated to lower income groups during 2021-22.

According to CMIE, the poorest households accounted for 9.8% of all the households and only 3.2% of all the unemployed before the pandemic in 2019-20. However, in 2020-21 and the first half of 2021-22 they accounted for 16.6% of all households but still accounted for only 3.5% of all the unemployed.

The richer households, however, suffer the least pain of unemployment. They account for about 0.5% of all households and contain a similar proportion of all unemployed. Their average LPR at 46.3% is the highest among all income groups.

As per CMIE, their unemployment rate had shot up the most among all income groups but has since declined. It was over 15% during the first wave of the pandemic. But, in 2021, the rate averaged at 5.2%. The employment rate has been mostly over 40% but shot up to 45% during September-December 2021.

“However, even India’s best case employment rate at 45% is much worse than the world average of 54%,” it concluded.

Apr 18, 2022

Riaz Haq

India’s auto market at a decade low; 6 red signals, from high fuel prices to chip shortage, stall the road to recovery this year

https://auto.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/industry/indias-auto...

HIGHLIGHTS

Over 40% idle capacity in auto industry

Tractor sales down for 7 consecutive months

Motorcycle and entry-level car demand under pressure

Implementation of OBD to increase 2W price by 6%-7%

No major indicator for rural market revival

Commodity prices soar by up to 200%

Fuel prices hover above INR 100/litre

PV exports at a decade low

Increase in booking cancellations

New Delhi: India’s automobile sales in the domestic market nosedived to 17.51 million in 2021-22, lowest since 2012-13 when the total wholesales were at 17.82 million, says the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM).

Two-wheelers, the worst-hit segment, declined to a decade low in 2021-2022 to 13,466,000 units. It was in 2011-2012 that the two-wheeler sales were close to this number at 13,409,00. In the peak year FY19, the nation's two-wheeler market was at over 21 million units.

The deficit in the ICE two-wheeler is incredibly wide even after adding the electric two-wheelers, including low-speed and high speed, which were at about 3 lakh units. ICE three-wheelers volume also remained at 260,000 units, less than 50% of the peak volumes, while the total installed capacity is over a million units. The electric vehicles are catching up the fastest in this segment with almost 35% penetration.

Apr 25, 2022

Riaz Haq

Majority of #India’s 900 Million #Workforce Stop Looking for Jobs. #Labor participation rate dropped from 46% to 40% in 5 years. Only 9% of #Indian #women are employed or looking for jobs. #unemployment #BJP #Modi #economy #Hindutva #IslamophobiaInIndia https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-24/majority-of-indi...

By Vrishti Beniwal

April 24, 2022, 4:31 PM PDT

India’s job creation problem is morphing into a greater threat: a growing number of people are no longer even looking for work.

Frustrated at not being able to find the right kind of job, millions of Indians, particularly women, are exiting the labor force entirely, according to new data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt, a private research firm in Mumbai.

Apr 26, 2022

Riaz Haq

#India NITI Aayog’s first “SDG India - Index & Dashboard 2019-20” report showed that of 28 states/UTs it mapped, #poverty went up in 22, #hunger in 24 and #income #inequality in 25 of those states/UTs. #unemployment #economy #COVID19 #BJP #Modi #Hindutva https://www.fortuneindia.com/opinion/how-many-are-poor-in-india/107883

First, the IMF’s estimation.

The IMF used (i) the HCES of 2011-12 (the fiscal year 2011 for the IMF) as the base and estimated consumption distribution for all the years until 2020-21 (IMF’s 2020) “via the use of estimates based on average per capita nominal PFCE growth” and (ii) also took into consideration “the average rupee food subsidy transfer to each individual” for the years of 2004-05 to 2020-21.

The second factor – taking the money value of subsidised and free ration for 2020-21 – was considered because it said without this any exercise of poverty estimation “solely on the basis of reported consumption expenditures will lead to an overestimation of poverty levels”.

Several questions arise out of this methodology. The first is its extensive use of HCES of 2011-12 while being dismissive of the HCES of 2017-18 (which showed poverty growing). The second is, PFCE maps the consumption expenditure of all Indians, rich or poor, except government consumption (GFCE), and doesn’t tell which segment (income level) of society spends how much – making it impossible to know the status of households, which can be considered for poverty estimation.

The third is about the IMF’s assumption that the subsidised and free ration (which started during the pandemic under the PMGKY) reached two-thirds of the population and that the free ration will continue forever (eliminating extreme poverty). The IMF report cheers the Aadhaar-linked ration cards. None of these assumptions can be taken at face value.

The CAG report tabled in Parliament earlier this month highlighted several flaws in the Aadhaar’s functioning, including 73% of faulty biometrics that people paid to correct, duplications and verification failures. Besides, one year after the mass exodus began in 2020, migrant workers had not received subsidised ration, forcing the Supreme Court to lambast the central government (for its failure to operationalise the App being developed for the purpose and work-in-progress “one-nation-one-ration card” system) and direct state governments to ensure ration to migrants.

And what happens when the free ration is discontinued after September 2022? The decline in extreme poverty would return, wouldn’t it? So, does the IMF believe this amounts to poverty elimination?

On the other hand, the WB report seeks to marry the NSSO’s 2011-12 HCES to private sector data, the CMIE’s Consumer Pyramid Household Survey (CPHS), to inform its poverty estimation.

This is when the WB report admits that (i) the CMIE’s CPHS data is not comparable with the NSSO’s and that (ii) it “reweighed CPHS to construct NSSO-compatible measures of poverty and inequality for the years 2015 to 2019”. It said the CPHS data needed to be transformed into “a nationally representative dataset”.

As for the CPHS data, an elaborate debate about its ability to capture poverty took place last year. Several economists, including Jean Dreze, pointed out “a troubling pattern of poverty underestimation in CPHS, vis-à-vis other national surveys”. Several others accused the CPHS of a pronounced bias in favour of the “well-off”, which the CMIE admitted and promised to look into.

Another question arises from the use of the CPHS.

If a private firm like the CMIE can carry out household surveys every month or every quarter (for example, its employment-unemployment data is monthly) why can’t the government with decades of institutional knowledge and experience and huge human and financial resources?

Apr 27, 2022

Riaz Haq

Latest CMIE data: Indian labor force participation has dropped from 46% in 2017 to 40%. This "discouraged worker effect" shows people are giving up looking for work. India is growing. Job creation must be core policy to ensure all growth is not at the top.

https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/india-s-jo...

India’s job creation problem is morphing into a greater threat: a growing number of people are no longer even looking for work.

Frustrated at not being able to find the right kind of job, millions of Indians, particularly women, are exiting the labor force entirely, according to new data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt, a private research firm in Mumbai.

With India betting on young workers to drive growth in one of the world’s fastest-expanding economies, the latest numbers are an ominous harbinger. Between 2017 and 2022, the overall labor participation rate dropped from 46% to 40%. Among women, the data is even starker. About 21 million disappeared from the workforce, leaving only 9% of the eligible population employed or looking for positions.

Now, more than half of the 900 million Indians of legal working age -- roughly the population of the U.S. and Russia combined -- don’t want a job, according to the CMIE.

“The large share of discouraged workers suggests that India is unlikely to reap the dividend that its young population has to offer,” said Kunal Kundu, an economist with Societe Generale GSC Pvt in Bengaluru. “India will likely remain in a middle-income trap, with the K-shaped growth path further fueling inequality.”

India’s challenges around job creation are well-documented. With about two-thirds of the population between the ages of 15 and 64, competition for anything beyond menial labor is fierce. Stable positions in the government routinely draw millions of applications and entrance to top engineering schools is practically a crapshoot.

Though Prime Minister Narendra Modi has prioritized jobs, pressing India to strive for “amrit kaal,” or a golden era of growth, his administration has made limited progress in solving impossible demographic math. To keep pace with a youth bulge, India needs to create at least 90 million new non-farm jobs by 2030, according to a 2020 report by McKinsey Global Institute. That would require an annual GDP growth of 8% to 8.5%.

“I’m dependent on others for every penny,” said Shivani Thakur, 25, who recently left a hotel job because the hours were so irregular.

Failing to put young people to work could push India off the road to developed-country status.

Though the nation has made great strides in liberalizing its economy, drawing in the likes of Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc, India’s dependency ratio will start rising soon. Economists worry that the country may miss the window to reap a demographic dividend. In other words, Indians may become older, but not richer.

A decline in labor predates the pandemic. In 2016, after the government banned most currency notes in an attempt to stamp out black money, the economy sputtered. The roll-out of a nationwide sales tax around the same time posed another challenge. India has struggled to adapt to the transition from an informal to formal economy.

Explanations for the drop in workforce participation vary. Unemployed Indians are often students or homemakers. Many of them survive on rental income, the pensions of elderly household members or government transfers. In a world of rapid technological change, others are simply falling behind in having marketable skill-sets.

For women, the reasons sometimes relate to safety or time-consuming responsibilities at home. Though they represent 49% of India’s population, women contribute only 18% of its economic output, about half the global average.

Apr 27, 2022

Riaz Haq

#India’s extreme #heatwave is thwarting #Modi’s plan to “feed the world”. India is experiencing relentless heat waves for the 2nd month in a row. This has now begun to wilt the country’s #agriculture sector, especially #wheat production. #ClimateEmergency https://qz.com/india/2160187/indias-heat-wave-will-impact-modis-whe...

India has been experiencing relentless heat waves for the second month in a row. This has now begun to wilt the country’s agriculture sector, especially wheat production.

A low yield, coupled with rising food inflation, would force the government to prioritise domestic consumption over exports, potentially tripping up prime minister Narendra Modi’s recent offer to help feed the world.

Apr 28, 2022

Riaz Haq

CMIE: #India's #unemployment rate jumped to 7.83% in April from 7.60% in March. #Urban #jobless rate soared to 9.22% from 8.28% in March. #Modi #BJP #economy #Hindutva #Islamophobia https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/india-s-un...

The unemployment rate in the country grew to 7.83 per cent in April from 7.60 per cent in March, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) data.

The unemployment rate in urban areas was higher at 9.22 per cent compared to 8.28 per cent in March, the data released on Monday showed.

In the rural area, the unemployment rate was at 7.18 per cent in April compared to 7.29 per cent in the previous month.

Unemployment rate was the highest in Haryana at 34.5 per cent followed by Rajasthan at 28.8 per cent, Bihar 21.1 per cent and Jammu and Kashmir 15.6 per cent, the data showed.

CMIE managing director Mahesh Vyas told PTI that it is important to note that the labour force participation rate and the employment rate also increased in April.

"This is a good development," Vyas said.

The employment rate rose from 36.46 per cent to 37.05 per cent in April, he added.

May 3, 2022

Riaz Haq

Can #Indian #economy survive a global downturn? #India's currency #INR is at an all-time low, #unemployment is high. #Food, #energy prices are rising. #COVID19 , #UkraineWar and the #Shanghai lockdown could derail the world economic recovery. #inflation https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/can-the-indian-economy...

Everyone was hoping this would be the year of recovery when the global economy climbed off its Covid-19 sickbed and took the first tentative steps towards normalcy. As we recovered from Omicron, there were faint hopes we might have put the illness behind us. That brief spurt of optimism now seems premature.

The grim truth is the world couldn’t be in a worse shape. For a start, Covid-19 hasn’t gone away. Then, there’s the Russia-Ukraine war, now stretching into its 77th day with no end in sight. If all that isn’t enough, Shanghai, China’s biggest industrial city, is still undergoing a prolonged lockdown and supply disruptions could throw the global economy out of gear.

-------------

Inflation has become a global phenomenon, and the Reserve Bank of India and other central banks are all hiking interest rates with more tightening to come. Throw in the falling rupee and that will push up the prices of all imports starting with oil, coal, steel and cement and other commodities. Inevitably, prices of everyday necessities to luxury goods will rise. The Indonesians have already banned edible oil exports which we need in large quantities and prices of pulses are also rising, driven in part by the Russia-Ukraine war. And as consumers abandon discretionary spending, this lowers tax revenues and leaves the government in a tighter-than-ever squeeze with less to spend on key projects.

---------------

Mercedes Benz’s India CEO has gone on record to say he doesn’t have enough vehicles to meet strong demand. On a different level, companies like Maruti and Hero are saying there’s insufficient demand for their lower-end vehicles, suggesting buyers in those categories are stalling on purchases due to financial worries. Throw in sliding stock markets for the more well-heeled and it’s clear discretionary spending will suffer.

Outsourcing to China where manufacturing was cheaper seemed like a great idea until now when the perils of putting all your production eggs in one basket are becoming clear. Over the last 30 years, China has become the world’s factory and there’s nothing left in the West. Take shipbuilding for instance. The world’s 10 top shipyards are in South Korea and China.

Now, with China in lockdown, it’s disrupting global supply lines and creating shortages globally. It’s unclear when Shanghai will get Xi’s all-clear to open up. We’ve seen from our own experience a two-to-three week lockdown doesn’t stamp out Covid-19 totally and Omicron is especially fast-spreading.

Can India escape the effects of a global slowdown? We emerged relatively unscathed in 1999 and also 2008. But now we’re more interlocked with the world and it’s tough to see us escaping the multiple blows that are striking different corners of the globe.

May 10, 2022

Riaz Haq

The Indian economy is being rewired. The opportunity is immense And so are the stakes

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2022/05/13/the-indian-economy-is-...

Who deserves the credit? Chance has played a big role: India did not create the Sino-American split or the cloud, but benefits from both. So has the steady accumulation of piecemeal reform over many governments. The digital-identity scheme and new national tax system were dreamed up a decade or more ago.

Mr Modi’s government has also got a lot right. It has backed the tech stack and direct welfare, and persevered with the painful task of shrinking the informal economy. It has found pragmatic fixes. Central-government purchases of solar power have kick-started renewables. Financial reforms have made it easier to float young firms and bankrupt bad ones. Mr Modi’s electoral prowess provides economic continuity. Even the opposition expects him to be in power well after the election in 2024.

The danger is that over the next decade this dominance hardens into autocracy. One risk is the bjp’s abhorrent hostility towards Muslims, which it uses to rally its political base. Companies tend to shrug this off, judging that Mr Modi can keep tensions under control and that capital flight will be limited. Yet violence and deteriorating human rights could lead to stigma that impairs India’s access to Western markets. The bjp’s desire for religious and linguistic conformity in a huge, diverse country could be destabilising. Were the party to impose Hindi as the national language, secessionist pressures would grow in some wealthy states that pay much of the taxes.

The quality of decision-making could also deteriorate. Prickly and vindictive, the government has co-opted the bureaucracy to bully the press and the courts. A botched decision to abolish bank notes in 2016 showed Mr Modi’s impulsive side. A strongman lacking checks and balances can eventually endanger not just demo cracy, but also the economy: think of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, whose bizarre views on inflation have caused a currency crisis. And, given the bjp’s ambivalence towards foreign capital, the campaign for national renewal risks regressing into protectionism. The party loves blank cheques from Silicon Valley but is wary of foreign firms competing in India. Today’s targeted subsidies could degenerate into autarky and cronyism—the tendencies that have long held India back.

Seizing the moment

For India to grow at 7% or 8% for years to come would be momentous. It would lift huge numbers of people out of poverty. It would generate a vast new market and manufacturing base for global business, and it would change the global balance of power by creating a bigger counterweight to China in Asia. Fate, inheritance and pragmatic decisions have created a new opportunity in the next decade. It is India’s and Mr Modi’s to squander. ■

May 12, 2022

Riaz Haq

Rajeev Matta

@RajeevMatta

India’s total debt in March 2014 was 53 lac crores. In March 2023 it will be 153 lac crores. He has added 100 lac crore in 8 years.

India’s debt to GDP ratio was 73.95% in Dec 20.

(1/n)

https://twitter.com/RajeevMatta/status/1525346057122885632?s=20&...

--------

Rajeev Matta

@RajeevMatta

Foreign reserves are under 600 billion dollars. The trade deficit in March 22 alone was 18.51 billion when we exported the most (an increase of 19.76%); the import too that month increased by 24.21% (they don’t highlight that).

(2/n)

------------

Rajeev Matta

@RajeevMatta

Besides paying for the trade deficit, the foreign reserves need to provide for 256 billion dollars of debt repayment by Sept 22. Imagine, with imports getting costlier where we will be then.

(3/n)

-------------

Rajeev Matta

@RajeevMatta

Indian banks, specially the govt ones are making merry. In FY 21, they wrote off loans worth Rs 2.02 lac crore and since 2014, a whopping 10.7 lac crores. 75% of this is by public sector banks. We all know who all borrowed and scooted or not paying back.

(4/n)

-------------

Rajeev Matta

@RajeevMatta

Finally, the GDP. We were going well at 8.26% in March '16 after which he punctured the tyres of the running car. Remember demonetization? We came down to 6.80 in 17; 6.53 in 18; 4.04 in 19 & -7.96 in 20. Who says pandemic and world economy are responsible for our halt?

(n/n)

May 14, 2022

Riaz Haq

Research article

Open Access

Published: 29 May 2020

A comparison of the Indian diet with the EAT-Lancet reference diet

Manika Sharma, Avinash Kishore, Devesh Roy & Kuhu Joshi

https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-0...

The average calorie intake/person/day in both rural (2214 kcal) and urban (2169 kcal) India is less than the reference diet (Table 1). In both rural and urban areas, people in rich households (top deciles of monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE)) consume more than 3000 kcal/day i.e. 20% more than the reference diet. Their calorie intake/person/day is almost twice as high as their poorest counterparts (households in the bottom MPCE deciles) who consume only 1645 kcals/person/day (Table 1).

-------

The average daily calorie consumption in India is below the recommended 2503 kcal/capita/day across all groups compared, except for the richest 5% of the population. Calorie share of whole grains is significantly higher than the EAT-Lancet recommendations while those of fruits, vegetables, legumes, meat, fish and eggs are significantly lower. The share of calories from protein sources is only 6–8% in India compared to 29% in the reference diet. The imbalance is highest for the households in the lowest decile of consumption expenditure, but even the richest households in India do not consume adequate amounts of fruits, vegetables and non-cereal proteins in their diets. An average Indian household consumes more calories from processed foods than fruits.

------------------

The EAT-Lancet reference diet is made up of 8 food groups - whole grains, tubers and starchy vegetables, fruits, other vegetables, dairy foods, protein sources, added fats, and added sugars. Caloric intake (kcal/day) limits for each food group are given and add up to a 2500 kcal daily diet [7]. We compare the proportional calorie (daily per capita) shares of the food groups in the reference diet with similar food groups in Indian Diets.

May 21, 2022

Riaz Haq

Our total consumption of wheat and atta is about 125kg per capita per year. Our per person per day calorie intake has risen from about 2,078 in 1949-50 to 2,400 in 2001-02 and 2,580 in 2020-21

By Riaz Riazuddin former deputy governor of the State Bank of Pakistan.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1659441/consumption-habits-inflation

As households move to upper-income brackets, the share of spending on food consumption falls. This is known as Engel’s law. Empirical proof of this relationship is visible in the falling share of food from about 48pc in 2001-02 for the average household. This is an obvious indication that the real incomes of households have risen steadily since then, and inflation has not eaten up the entire rise in nominal incomes. Inflation seldom outpaces the rise in nominal incomes.

Coming back to eating habits, our main food spending is on milk. Of the total spending on food, about 25pc was spent on milk (fresh, packed and dry) in 2018-19, up from nearly 17pc in 2001-01. This is a good sign as milk is the most nourishing of all food items. This behaviour (largest spending on milk) holds worldwide. The direct consumption of milk by our households was about seven kilograms per month, or 84kg per year. Total milk consumption per capita is much higher because we also eat ice cream, halwa, jalebi, gulab jamun and whatnot bought from the market. The milk used in them is consumed indirectly. Our total per person per year consumption of milk was 168kg in 2018-19. This has risen from about 150kg in 2000-01. It was 107kg in 1949-50 showing considerable improvement since then.

Since milk is the single largest contributor in expenditure, its contribution to inflation should be very high. Thanks to milk price behaviour, it is seldom in the news as opposed to sugar and wheat, whose price trend, besides hurting the poor is also exploited for gaining political mileage. According to PBS, milk prices have risen from Rs82.50 per litre in October 2018 to Rs104.32 in October 2021. This is a three-year rise of 26.4pc, or per annum rise of 8.1pc. Another blessing related to milk is that the year-to-year variation in its prices is much lower than that of other food items. The three-year rise in CPI is about 30pc, or an average of 9.7pc per year till last month. Clearly, milk prices have contributed to containing inflation to a single digit during this period.

Next to milk is wheat and atta which constitute about 11.2pc of the monthly food expenditure — less than half of milk. Wheat and atta are our staple food and their direct consumption by the average household is 7kg per capita (84kg per capita per year). As we also eat naan from the tandoors, bread from bakeries etc, our indirect consumption of wheat and atta is 41kg per capita. Our total consumption of wheat and atta is about 125kg per capita per year. Our per person per day calorie intake has risen from about 2,078 in 1949-50 to 2,400 in 2001-02 and 2,580 in 2020-21. The per capita per day protein intake in grams increased from 63 to 67 to about 75 during these years. Does this indicate better health? To answer this, let us look at how we devour ghee and sugar. Also remember that each person requires a minimum of 2,100 calories and 60g of protein per day.

Undoubtedly, ghee, cooking oil and sugar have a special place in our culture. We are familiar with Urdu idioms mentioning ghee and shakkar. Two relate to our eating habits. We greet good news by saying ‘Aap kay munh may ghee shakkar’, which literally means that may your mouth be filled with ghee and sugar. We envy the fortune of others by saying ‘Panchon oonglian ghee mei’ (all five fingers immersed in ghee, or having the best of both worlds). These sayings reflect not only our eating trends, but also the inflation burden of the rising prices of these three items — ghee, cooking oil and sugar. Recall any wedding dinner. Ghee is floating in our plates.

May 21, 2022

Riaz Haq

Comparative performance: Global Hunger Index

https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/persistence-food-insecurity-ma...

India has been performing poorly in global rankings of hunger. It ranks 101st out of 116 countries on the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2021......

The Global Hunger Report 2021 gives comparable GHI scores for four separate years between 2000 and 2021. 2 Table 1 compares the GHI for India with four countries: all ranking better than India currently but with GHI scores close to or worse than India’s in 2000. This shows the relatively slow improvement in India. Cambodia which in 2000 had a GHI of 41.1, higher than India’s 38.8, managed by 2021 to reduce its score to 17, while India could lower it to only 27.5. During this period Cambodia moved from the ‘Alarming’ to the ‘Moderate’ category, while India moved from ‘Alarming’ to ‘Serious’.

When the GHI was released a few months back, India put out an official press note claiming that the index used flawed methodology and was not a true reflection of hunger in the country. The main official objections were two-fold. First, that the GHI was based on a phone survey conducted on a small sample and therefore not representative of the true picture in the country. This was not true. The authors of the report clarified that anyone who read the report could see that the data used were not from any phone survey, but, rather, based on official indicators from government or UN sources.

The second objection, which representatives of the NITI Ayog and others have written about, is that while the GHI is called a ‘hunger’ index, it actually measures malnutrition. This is nothing but engaging in semantics while trying to distract attention from the more substantial issues. As explained by the Global Hunger Report, “Hunger is usually understood to refer to the distress associated with a lack of sufficient calories. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines food deprivation, or undernourishment, as the consumption of too few calories to provide the minimum amount of dietary energy that each individual requires to live a healthy and productive life, given that person’s sex, age, stature, and physical activity level.” The GHI includes measures of population undernourishment, childhood stunting, childhood wasting and child mortality and tries to capture it in a broader sense of food insecurity and malnutrition.

Hunger in India

Measuring hunger has been deeply controversial in India and globally, but the most common way in which it is done is by looking at adequacy of food consumption in calorie terms. Some analysis based on the data from the 2017–18 NSS consumption expenditure survey, as available in a leaked report (and analysed in the The India Forum), showed that mean consumption expenditure, as well as the mean consumption expenditure on food, declined between 2011–12 and 2017–18. These declines in average per capita consumption expenditures on food most likely reflect an increase in hunger amongst the poor (Subramanian, 2019). A decline in real food consumption expenditure also indicates an increase in poverty.

----

As can be seen in Figure 2, while the undernourishment in India showed a secular decline from around 2005 onwards, the last few years have shown a reversal of this trend. Both as a proportion and in absolute numbers, there has been an increase in the prevalence of undernutrition after 2016. The prevalence of undernutrition, taken as a three-year moving average, was 13.8% for 2016–18, going up to 14% in 2017–19, and 15.3% in 2018–20. This data does not take into account the pandemic years, which based on all indications can be expected to have been worse.

May 24, 2022

Riaz Haq

‘Diet of Average Indian Lacks Protein, Fruit, Vegetables’

On average, the Indian total calorie intake is approximately 2,200 kcals per person per day, 12 per cent lower than the EAT-Lancet reference diet's recommended level.

https://www.india.com/lifestyle/diet-of-average-indian-lacks-protei...

Compared to an influential diet for promoting human and planetary health, the diets of average Indians are considered unhealthy comprising excess consumption of cereals, but not enough consumption of proteins, fruits and vegetables, said a new study.Also Read - Autistic Pride Day 2020: Diet Rules For Kids With Autism

The findings by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and CGIAR research program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH) broadly apply across all states and income levels, underlining the challenges many Indians face in obtaining healthy diets. Also Read - Vitamin K Rich Food: Include These Items in Your Daily Diet to Avoid Uncontrolled Bleeding

“The EAT-Lancet diet is not a silver bullet for the myriad nutrition and environmental challenges food systems currently present, but it does provide a useful guide for evaluating how healthy and sustainable Indian diets are,” said the lead author of the research article, A4NH Program Manager Manika Sharma. Also Read - Experiencing Hair Fall? Include These Super-foods in Your Daily Diet ASAP

“At least on the nutrition front we find Indian diets to be well below optimal.”

The EAT-Lancet reference diet, published by the EAT-Lancet Commission on Food, Planet, and Health, implies that transforming eating habits, improving food production and reducing food wastage is critical to feed a future population of 10 billion a healthy diet within planetary boundaries.

While the EAT-Lancet reference diet recommends eating large shares of plant-based foods and little to no processed meat and starchy vegetables, the research demonstrates that incomes and preferences in India are driving drastically different patterns of consumption.

May 24, 2022

Riaz Haq

Why is India's economy looking so bleak?

https://qz.com/india/2170008/why-is-indias-economy-looking-so-bleak/

https://vigourtimes.com/why-is-indias-economy-looking-so-bleak-quar...

There's an apocalyptic nature to the way things feel and look right now.

Overnight news of a crash and slide for the Dow and Nasdaq bring fears every morning of another stock market rout in India. The rupee is in completely new and scary territory now slip- sliding towards the 80-mark to the dollar. Crude has shown no inclination to ease back from the triple digits it now trades in.

All this is what grabs headlines and eyeballs. But to call a spade a spade, the stock market represents and holds only a minuscule fraction of India's population and investing community within it. It is undoubtedly called the barometer of sentiment but whose sentiment does it reflect and is it only now that things have turned bad?

Go back a few years to the red-letter demonetisation day on Nov. 8, 2016. On the face of it, both the country and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party government emerged intact from a dangerous experiment. What went unnoticed—or certainly, unreported by mainstream media—was the devastation it wreaked on small and medium businesses. That devastation has turned into a slow but fatal grind, pulverising business after business.

What sucking out cash from the system did in 2016, was followed up by a patchwork rollout of the Goods and Services Tax in 2017. More pressure. The final nail in the coffin has been the insidious rise and rise of inflation. In April this year, inflation at the retail level surged to an eight-year high of 7.79%. The wholesale price index hit a record high of 15.1%, the outcome of rising prices of vegetables, fruits, milk, manufacturing, fuel, and power.

Lest we begin to blame it all on the war in Ukraine, inflation has remained in double digits for 13 months in a row now. A red flag that was waving in the air for many months, and now seems to have the Reserve Bank of India's full attention.

Biting the bullet

Large businesses have responded. Consumer goods companies have decided to bite the cost bullet. Prices of goods have been…

-------------

Key lessons

But it leaves important lessons to think about. What did I learn from this, was I truly looking at investing when I picked up the small cap stock? Do I know enough to be trading in the futures and options market, sharp as a knife and fast as a bullet? A young India that was bedazzled by the cryptocurrency market will also have to collect its broken earnings and dreams. India has been one of the world’s fastest-growing cryptocurrency markets, increasing by 641% between July 2020 and June 2021. Much of that was India’s young population, from the B and C cities. In the crash burn we have seen this year, many young traders have been left singed.

The ultimate lesson, I believe, is this. When there is a cancer in the system, it will spread. For all those who believed the market, or one segment of the economy, would continue to grow even as the broader market and population was crumbling under the pressure of the last few years, it has not worked that way.

May 25, 2022

Riaz Haq

Why is India's economy looking so bleak?

https://qz.com/india/2170008/why-is-indias-economy-looking-so-bleak/

https://vigourtimes.com/why-is-indias-economy-looking-so-bleak-quar...

Biting the bullet

Large businesses have responded. Consumer goods companies have decided to bite the cost bullet. Prices of goods have been increased, package sizes will get smaller, and downtrading—switching from expensive products to cheaper alternatives—is the new reality for daily household purchases. The construction of homes will get more expensive as the prices of cement, transportation, materials all climb higher.

Do small businesses have the same luxury and leeway? Not really. In an interview to the Business Standard, Jitubhai Vakharia, the president of the South Gujarat Textile Processors’ Association in Surat, explained how the input cost of coal has almost doubled. The cost of dyes and chemicals have increased by 25% to 40% and the price of some chemicals like sodium hydrosulphite of soda or discharging agent like safolite have increased by 140% to 150%. Input costs have increased he says.

So can they raise costs? Increasing prices is difficult he admitted, as demand is already low in the market.

What that means is, more business could be forced to close, more jobs are lost, and more households are left wondering how they will get by. The government’s own data shows that 5,907 businesses registered as micro, small, and medium enterprises were shut during financial years 2020-’21 and 2021-’22. In the 2021 financial year, 330 MSMEs were shut down.

It is perhaps with an eye to this simmering discontent around price rise and seeing the neighbouring country of Sri Lanka quite literally go up in flames over spiralling inflation, that finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced on Saturday an excise cut in petrol and diesel taxes and a 200 rupees ($2.58) subsidy for those buying cooking gas cylinders, along with some customs duty cuts. While the move is being criticised as an optical illusion, the Narendra Modi government has clearly sensed dissatisfaction around the way costs have risen and moved to do some damage control.

The latest State of Inequality in India Report by the economic advisory council to the prime minister had these observations to share. The income of the top 1% shows a growing trend, while that of the bottom 10% is shrinking—the top 1% of income earners in India cumulatively earn more than three times of what is earned by the bottom 10%. Within that, a person who earns an average of Rs25,000 per month is now part of the top 10% of the total wages earned bracket. What does that mean for the others, what are people earning and how are they getting by in an environment of continuous cost rise?

This economic strife also begets the question, why doesn’t it translate into protests, electoral punishment? Why aren’t people voting out governments when they feel the pressure of rising costs, no jobs, and less and less ability to spend?

May 25, 2022

Riaz Haq

Why is India's economy looking so bleak?

https://qz.com/india/2170008/why-is-indias-economy-looking-so-bleak/

https://vigourtimes.com/why-is-indias-economy-looking-so-bleak-quar...

This economic strife also begets the question, why doesn’t it translate into protests, electoral punishment? Why aren’t people voting out governments when they feel the pressure of rising costs, no jobs, and less and less ability to spend?

Difficult conditions

One, this does not have a singular unified impact. In the run-up to the Uttar Pradesh elections, many roving reporters thrust their mikes into the faces of people. What do you worry about, what is a concern, they were asked? “Mehengai,” the rising cost of living, the interviewees would respond. Prices of cooking oils like mustard oil and sunflower oil had risen, gas cylinder prices were up, jobs were scarce and running a household was an uphill struggle. India’s overall unemployment rate rose to 7.83% in April, up from 7.6% in March.

Yet, it did not impact voting choices and the ruling state government was elected back with a clear majority. It is because my inflation is not your inflation. My household cost pressures are not yours. I have a job, but you don’t. Cost rise is too fluid and wide a challenge to cement together an entire population into making a political choice borne of it.

There is also the insulation that welfare schemes have created for the very poor. Food schemes, cash transfers, and some workdays through the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee, which assures rural families of 100 days of work a year. The slice left vulnerable and besieged is India’s large and diverse middle class that is now feeling the pain. Households that own a motorcycle and dream of a small car, households that want to move from their one-bedroom rented accommodation, to a two-bedroom home of their own.

The rise of political marketing

Two, we now have a changed polity. With close to 500 million users, India has the most WhatsApp users. All of whom have been nursed with consistent messaging around political agenda. If the last 10 years have seen economic missteps, they have equally been marked by the rise of marketing in politics. More than Rs6,500 crore was spent on elections by 18 political parties between 2015 and 2020. Of this, political parties spent more than Rs3,400 crore or 52.3% on publicity alone.

The Bharatiya Janata Party spent 56% (over Rs3,600 crore) of the total election outlay by all 18 parties in the five years and Congress spent 21.41% (over Rs1,400 crore). In the last five years, the BJP has spent 54.87% (over Rs2,000 crore) of their total election expenditure on “advertisements and publicity” compared to 7.2% (Rs260 crore) on marches, rallies, and other campaigns. The Congress, in the five-year period, has spent 40.08% (Rs 560 crore) of the total election expenditure on election-related publicity.

Does all this matter? Higher public expenditure on publicity and advertising in an election year is a major factor for a state government to retain power, In a May 2021 State Bank of India report titled “State Elections: How Women are Shaping India’s Destiny,” Soumya Kanti Ghosh. the Group Chief Economic Adviser, writes that in most of the states, on an average in order to be re-elected, incumbent governments make huge spends in an election year.

May 25, 2022

Riaz Haq

Why is India's economy looking so bleak?

https://qz.com/india/2170008/why-is-indias-economy-looking-so-bleak/

https://vigourtimes.com/why-is-indias-economy-looking-so-bleak-quar...

Does all this matter? Higher public expenditure on publicity and advertising in an election year is a major factor for a state government to retain power, In a May 2021 State Bank of India report titled “State Elections: How Women are Shaping India’s Destiny,” Soumya Kanti Ghosh. the Group Chief Economic Adviser, writes that in most of the states, on an average in order to be re-elected, incumbent governments make huge spends in an election year.

In a few states where publicity expenditure was low in election year, the incumbent government mostly lost the election. It may be fair to say then that this marketing blitz can mould voter opinion, whether it is to highlight the benefits of a regime—or to demonise a section of the population.

What does all this have to do with the stock market that’s battling its own losses and the fear of a prolonged bear trading patch? It is an ugly situation for markets, there’s no denying. Selling in the equity universe will come in waves and lashes, this purging of stocks, prices, and holdings. However, this too shall pass. It may leave the markets in a dull trading range for many months where things move neither higher nor lower. Or it may bounce back faster than expected, egged on by better global news and the return of the prodigal foreign institutional investors.

Key lessons

But it leaves important lessons to think about. What did I learn from this, was I truly looking at investing when I picked up the small cap stock? Do I know enough to be trading in the futures and options market, sharp as a knife and fast as a bullet? A young India that was bedazzled by the cryptocurrency market will also have to collect its broken earnings and dreams. India has been one of the world’s fastest-growing cryptocurrency markets, increasing by 641% between July 2020 and June 2021. Much of that was India’s young population, from the B and C cities. In the crash burn we have seen this year, many young traders have been left singed.

The ultimate lesson, I believe, is this. When there is a cancer in the system, it will spread. For all those who believed the market, or one segment of the economy, would continue to grow even as the broader market and population was crumbling under the pressure of the last few years, it has not worked that way.

It is also true that we still remain a nation of great potential, a large working force, a diverse geography, a huge market size. But will India continue to walk into the future with only a rich few, or will we take all our people with us? As James Baldwin wrote, “Neither love nor terror makes one blind; indifference makes one blind.”

This article first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.

May 25, 2022

Riaz Haq

As the wealthy converge on Davos to discuss the world’s problems, a case for taxing the rich

Harsh Mander and Prabhat Patnaik discuss funding universal social and economic rights, not just a universal basic income, in a time of widening inequalities.

https://scroll.in/article/1024582/as-the-wealthy-converge-on-davos-...

For instance, you look at per capita food intake. The proportion of people [consuming] below 2,200 calories per day in rural India, which is supposed to be the benchmark for poverty, in 1993-’94 was about 58%. You look at 2011, it was 68%. In urban India, corresponding, it was 57% and 65%.

What has happened now is that education and healthcare are much more expensive, none of which gets captured in the consumer price index. As a result, people are forced to spend so much on these that they actually skimp on buying food.

-------

Mander: I was struck by the latest World Development Report. It is perhaps the first major admission by the Bretton Woods set of institutions [World Bank and International Monetary Fund] that we may not be able to produce jobs, that jobless growth is actually not an aberration, but is almost written into the nature of [the] neoliberal model. But the solution that they want to give is universal basic income.

Prabhat Patnaik: Exactly. However, suppose everybody gets a certain amount of money, but with no school or government hospital within their radius. In that case, the idea of simply handing you money just does not help. It is very important that actual essential services and commodities must be made available to everybody, including work opportunities. And this is what the welfare state actually promised you.

Harsh Mander: Suppose I have a child with disabilities, I have many more economic needs than someone who does not. So a basic income and top-up idea is also blind to those questions.

My next question is with the conversation about universal social rights, which rights are we speaking about?

Prabhat Patnaik: Well, you can think in terms of a very wide range of rights. In my writings, I have essentially been talking about five economic rights. But I am not sticking to just those five, and neither am I saying that these five should take priority over other kinds of rights.

Harsh Mander: And these five are: employment, healthcare, school education, pensions, and food and nutrition.

Prabhat Patnaik: That’s right. So I am talking about just these five because I made some calculations based on them.