PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and 3.5 million entrepreneurs in November alone. Many among the unemployed can no longer afford to buy food, causing a significant spike in hunger. The country's economy is finding it hard to recover from COVID waves and lockdowns, according to data from multiple sources. At the same time, the Indian government has reported an 8.4% jump in economic growth in the July-to-September period compared with a contraction of 7.4% for the same period a year earlier. This raises the following questions: Has India had jobless growth? Or its GDP figures are fudged? If the Indian economy fails to deliver for the common man, will Prime Minister Narendra Modi step up his anti-Pakistan and anti-Muslim rhetoric to maintain his popularity among Hindus?

|

| Labor Participation Rate in India. Source: CMIE |

Unemployment Crisis:

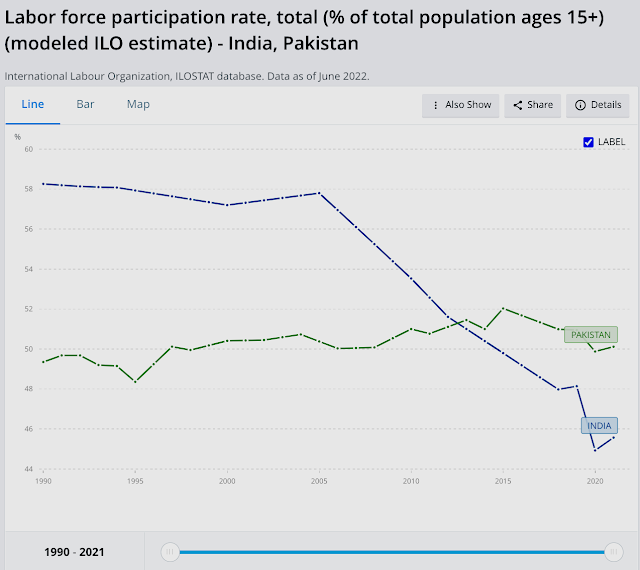

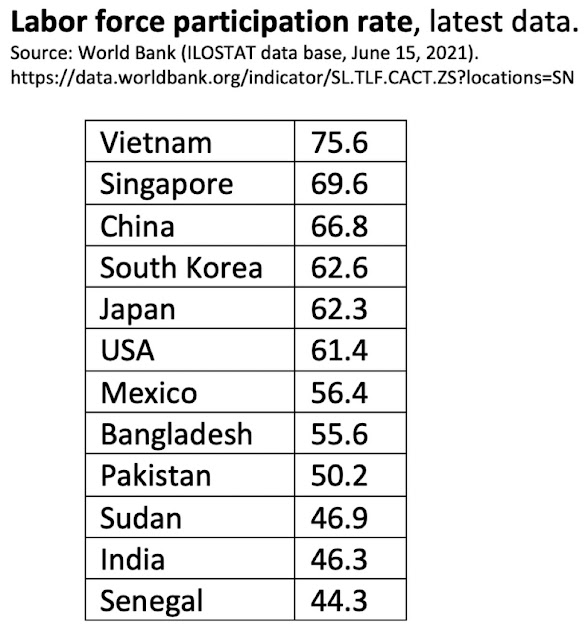

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and its labor participation rate (LPR) slipped from 40.41% to 40.15% in November, 2021, according to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). In addition to the loss of salaried jobs, the number of entrepreneurs in India declined by 3.5 million. India's labor participation rate of 40.15% is lower than Pakistan's 48%. Here's an except of the latest CMIE report:

"India’s LPR is much lower than global levels. According to the World Bank, the modelled ILO estimate for the world in 2020 was 58.6 per cent (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.ZS). The same model places India’s LPR at 46 per cent. India is a large country and its low LPR drags down the world LPR as well. Implicitly, most other countries have a much higher LPR than the world average. According to the World Bank’s modelled ILO estimates, there are only 17 countries worse than India on LPR. Most of these are middle-eastern countries. These are countries such as Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Syria, Senegal and Lebanon. Some of these countries are oil-rich and others are unfortunately mired in civil strife. India neither has the privileges of oil-rich countries nor the civil disturbances that could keep the LPR low. Yet, it suffers an LPR that is as low as seen in these countries".

|

| Labor Participation Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: World Bank/ILO |

|

| Labor Participation Rates for Selected Nations. Source: World Bank/ILO |

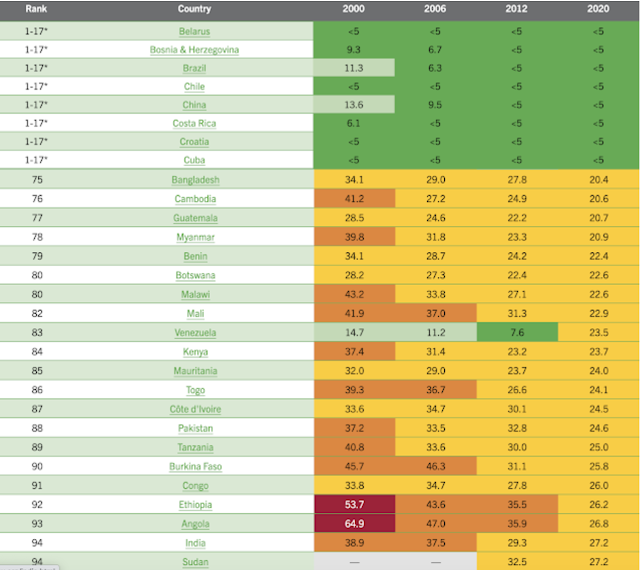

Youth unemployment for ages15-24 in India is 24.9%, the highest in South Asia region. It is 14.8% in Bangladesh 14.8% and 9.2% in Pakistan, according to the International Labor Organization and the World Bank.

|

| Youth Unemployment in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Source: ILO, WB |

In spite of the headline GDP growth figures highlighted by the Indian and world media, the fact is that it has been jobless growth. The labor participation rate (LPR) in India has been falling for more than a decade. The LPR in India has been below Pakistan's for several years, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

|

| Indian GDP Sectoral Contribution Trend. Source: Ashoka Mody |

|

| Indian Employment Trends By Sector. Source: CMIE Via Business Standard |

|

| World Hunger Rankings 2020. Source: World Hunger Index Report |

Hunger and malnutrition are worsening in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia because of the coronavirus pandemic, especially in low-income communities or those already stricken by continued conflict.

India has performed particularly poorly because of one of the world's strictest lockdowns imposed by Prime Minister Modi to contain the spread of the virus.

Hanke Annual Misery Index:

Pakistan's Real GDP:

Vehicles and home appliance ownership data analyzed by Dr. Jawaid Abdul Ghani of Karachi School of Business Leadership suggests that the officially reported GDP significantly understates Pakistan's actual GDP. Indeed, many economists believe that Pakistan’s economy is at least double the size that is officially reported in the government's Economic Surveys. The GDP has not been rebased in more than a decade. It was last rebased in 2005-6 while India’s was rebased in 2011 and Bangladesh’s in 2013. Just rebasing the Pakistani economy will result in at least 50% increase in official GDP. A research paper by economists Ali Kemal and Ahmad Waqar Qasim of PIDE (Pakistan Institute of Development Economics) estimated in 2012 that the Pakistani economy’s size then was around $400 billion. All they did was look at the consumption data to reach their conclusion. They used the data reported in regular PSLM (Pakistan Social and Living Standard Measurements) surveys on actual living standards. They found that a huge chunk of the country's economy is undocumented.

Pakistan's service sector which contributes more than 50% of the country's GDP is mostly cash-based and least documented. There is a lot of currency in circulation. According to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the currency in circulation has increased to Rs. 7.4 trillion by the end of the financial year 2020-21, up from Rs 6.7 trillion in the last financial year, a double-digit growth of 10.4% year-on-year. Currency in circulation (CIC), as percent of M2 money supply and currency-to-deposit ratio, has been increasing over the last few years. The CIC/M2 ratio is now close to 30%. The average CIC/M2 ratio in FY18-21 was measured at 28%, up from 22% in FY10-15. This 1.2 trillion rupee increase could have generated undocumented GDP of Rs 3.1 trillion at the historic velocity of 2.6, according to a report in The Business Recorder. In comparison to Bangladesh (CIC/M2 at 13%), Pakistan’s cash economy is double the size. Even a casual observer can see that the living standards in Pakistan are higher than those in Bangladesh and India.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Counterparts

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade Deficits

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Riaz Haq

#India's #Jobs #crisis: urban unemployment at 9.1%, highest in 4 months. 29.3% Haryana tops in #unemployment, followed by #Kashmir 21.4%, #Rajasthan 20.4%, #Bihar 14.8%, Himachal Pradesh 13.6%, Tripura 13.4%, Goa 12.7% & Jharkhand 11.2%. #Modi #economy https://www.dailypioneer.com:443/2021/india/urban-unemployment-9-1-...

The urban unemployment rate stood at 9.1 per cent as on December 18 which is the highest since August. The all India unemployment rate recorded 7.6 per cent as on December 17 which is also high as compared to 7 per cent in November. The rural unemployment rate stood at 6.9 per cent as compared to 6.44 per cent in November. Unemployment is going to be a major poll issue in the upcoming assembly polls in five states.

The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), which tracks the labour market with proprietary tools, showed that with 29.3 per cent Haryana is in the top among the states and union territories in unemployment, followed by Jammu and Kashmir with 21.4 per cent and Rajasthan with 20.4 per cent. Bihar ( 14.8 per cent), Himachal Pradesh ( 13.6 per cent), Tripura ( 13.4 per cent), Goa ( 12.7 per cent) and Jharkhand ( 11.2 per cent) are among those states having double digit unemployment in December. The unemployment rate in Delhi is recorded at 9.3 per cent.

The data showed the unemployment rate declined from 7.8 per cent in October to 7 per cent in November; the employment rate rose by a whisker from 37.28 per cent to 37.34 per cent. This translated into employment increasing by 1.4 million, from 400.8 million to 402.1 million in November 2021.

India's unemployment rate at the national level stood at 7.75 per cent in October, 6.86 per cent in September, 8.32 per cent in August, 6.96 per cent in July, 9.17 per cent in June and 11.84 per cent in May. The Urban unemployment rate stood at 7.38 per cent in October, 8.62 per cent in September, 9.78 per cent in August, 8.32 per cent in July, 10.08 per cent in June and 14.72 per cent in May. The rural unemployment rate stood at 7.91 per cent in October, 6.06 per cent in September, 7.64 per cent in August, 6.34 per cent in July, 8.75 per cent in June and 10.55 per cent in May.

According to the CMIE, the data in November showed the labour participation rate (LPR) has slipped. It fell from 40.41 per cent in October to 40.15 per cent in November. This is the second consecutive month of a fall in the LPR. Cumulatively, the LPR has fallen by 0.51 percentage points over October and November 2021. This makes it a significant fall in the LPR compared to average changes seen in other months if we exclude the months of economic shock such as the lockdown.

As per the CMIE, the creation of additional jobs pushed up India’s employment rate to 37.87% in September as compared to 37.15% in August. Further, the employment rate in rural India jumped by 0.85 percentage points to 39.53% in September as against 38.68% in August while that in urban India grew to 34.62% compared with 34.15% in August. Of the 8.5 million additional people employed in September, 6.5 million or 76.5% of the total employment generation was in rural India,” CMIE stated in its weekly labour market analysis early this month.

Dec 22, 2021

Riaz Haq

World #Inequality report 2022 says #India is one of the world' most unequal countries, with rising #poverty & an affluent elite. Govt policies have had a negative impact on the #poor while making the #rich even richer. #Modi #BJP #Islamophobia #Hindutva https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/12/23/1065267029/a-c...

If growth had been distributed more equally since the 1990s, there would be less poverty today and more middle-class families, says Chancel. In order to generate prosperity for the bottom 50% of the population, public investments are key — equal access to basic services such as quality education, transport and health, says Chancel. "This is still lacking in India."

--------------

According to the World Food Program, a quarter of the world's undernourished people live in India. And despite steady economic growth and per capita income having tripled in recent years, the WFP notes that minimum dietary intake fell.

-----------

It's almost as if there are two countries in India: a very small, very rich country (the country of prosperous Indian urban centers) and a very large, poor country, says Lucas Chancel, lead author of the report and co-director of the World Inequality Lab. "For a long time, it has been said that the richer the rich part of the country, the better for the rest," he says.

The coconut seller Pachavarnam hasn't felt that, though. And experts like Chancel acknowledge that this is an outlook that's left many families vulnerable.

A coconut vendor says she's 'terrified of the future'

Panchavarnam, who goes by one name, has sold tender coconuts on the streets of Madurai for the last 40 years and remembers a time when the bustling residential neighborhood where she now sells her wares used to be a forest. Today, it's filled with signs of development. There's a highway close by. Busy streets brim over with traffic. In the last decade, apartment complexes, department stores and schools have sprung up around her.

For the 50-year-old, however, little has changed.

She still works 12 hours a day. It's a job she's been doing since the age of 9 helping her dad. That's when she first learned how to hold a sickle to slice into the thick, fibrous coconut. She and her husband begin their workday at 5 a.m., when she buys the coconuts from a wholesale market to fill their rented cart.

She may sell her coconuts at a higher price than she did ten years ago, but her family's daily living expenses and rental for her cart have increased too. Inflation has skyrocketed. But even though her profit may be wafer thin, she's grateful she can at least work.

"During the lockdown, we suffered a lot," she says. "It struck me then how little we had saved. For the first time, I was terrified of the future. What would happen to me and my family if we could no longer work?"

Panchavarnam is one of India's many informal workers, an estimated 485 million people — which according to a 2014 survey by the government of India's Labour Bureau is roughly 50% of the national workforce. Some reports estimate that their numbers are far higher — almost 80% of the workforce. While Panchavarnam is self-employed, other informal workers are hired by companies. But their situation isn't necessarily any easier.

A female construction worker's dusty burden

Selvi, 37, is a construction worker in Chennai, a city in Southern India, who earns Rs 350 ($4.60) a day, carrying heavy loads of cement, bricks and gravel. She winds a thick cloth turban style over her head and places her loads directly on it.

https://wir2022.wid.world/www-site/uploads/2021/12/Summary_WorldIne...

Dec 23, 2021

Riaz Haq

India’s Stalled Rise

How the State Has Stifled Growth

By Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman

January/February 2022

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2021-12-14/indias-sta...

As growth slowed, other indicators of social and economic progress deteriorated. Continuing a long-term decline, female participation in the labor force reached its lowest level since Indian independence in 1948. The country’s already small manufacturing sector shrank to just 13 percent of overall GDP. After decades of improvement, progress on child health goals, such as reducing stunting, diarrhea, and acute respiratory illnesses, stalled.

And then came COVID-19, bringing with it extraordinary economic and human devastation. As the pandemic spread in 2020, the economy withered, shrinking by more than seven percent, the worst performance among major developing countries. Reversing a long-term downward trend, poverty increased substantially. And although large enterprises weathered the shock, small and medium-sized businesses were ravaged, adding to difficulties they already faced following the government’s 2016 demonetization, when 86 percent of the currency was declared invalid overnight, and the 2017 introduction of a complex goods and services tax, or GST, a value-added tax that has hit smaller companies especially hard. Perhaps the most telling statistic, for an economy with an aspiring, upwardly mobile middle class, came from the automobile industry: the number of cars sold in 2020 was the same as in 2012.

--------

Adding to a decade of stagnation, the ravages of COVID-19 have had a severe effect on Indians’ economic outlook. In June 2021, the central bank’s consumer confidence index fell to a record low, with 75 percent of those surveyed saying they believed that economic conditions had deteriorated, the worst assessment in the history of the survey.

Dec 24, 2021

Riaz Haq

India’s Stalled Rise

How the State Has Stifled Growth

By Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman

January/February 2022

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2021-12-14/indias-sta...

For the Indian economy to achieve its potential, however, the government will need a sweeping new approach to policy—a reboot of the country’s software. Its industrial policy must be reoriented toward lower trade barriers and greater integration into global supply chains. The national champions strategy should be abandoned in favor of an approach that treats all firms equally. Above all, the policymaking process itself needs to be improved, so that the government can establish and maintain a stable economic environment in which manufacturing and exports can flourish.

But there is little indication that any of this will occur. More likely, as India continues to make steady improvements in its hardware—its physical and digital infrastructure, its New Welfarism—it will be held back by the defects in its software. And the software is likely to prove decisive. Unless the government can fundamentally improve its economic management and instill confidence in its policymaking process, domestic entrepreneurs and foreign firms will be reluctant to make the bold investments necessary to alter the country’s economic course.

There are further risks. The government’s growing recourse to majoritarian and illiberal policies could affect social stability and peace, as well as the integrity of institutions such as the judiciary, the media, and regulatory agencies. By undermining democratic norms and practices, such tendencies could have economic costs, too, eroding the trust of citizens and investors in the government and creating new tensions between the federal administration and the states. And India’s security challenges on both its eastern and its western border have been dramatically heightened by China’s expansionist activity in the Himalayas and the takeover of Afghanistan by the Pakistani-supported Taliban.

If these dynamics come to dominate, the Indian economy could experience another disappointing decade. Of course, there would still be modest growth, with some sectors and some segments of the population doing particularly well. But a broader boom that transforms and improves the lives of millions of Indians and convinces the world that India is back would be out of reach. In that case, the current government’s aspirations to global economic leadership may prove as elusive as those of its predecessors.

Dec 24, 2021

Riaz Haq

Manufacturing employment nearly half of what it was five years ago

Manufacturing accounts for nearly 17% of India's GDP, but the sector has seen employment decline sharply in last 5 years - from employing 51 million Indians in 2016-17 to reach 27.3 million in 2020-21

https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/ceda-cmie-...

With the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic battering India at present, the Indian economic outlook looks bleak for the second year in a row. In 2020-21, India’s real GDP growth is estimated to be minus 8 per cent. This would also put pressure on India’s employment numbers. In previous bulletins, we have analysed the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on employment, individual and household incomes and expenditures in 2020.

In this CEDA-CMIE Bulletin, we try to take a longer-term view of sector-wise employment in India. We base this on CMIE’s monthly time-series of employment by industry going back to the year 2016. For this bulletin, we have focused on seven sectors – agriculture, mines, manufacturing, real estate and construction, financial services, non-financial services, and public administrative services. These sectors make up for 99 per cent of total employment in the country.

In figure 2 and 3 (below), we look at four sectors. These are agriculture, financial services, non-financial services, and public administrative services. Non-financial services exclude public administrative services and defense services. Together, these accounted for 69 per cent of total employment in 2016-17 and 78 per cent in 2020-21.

The agriculture sector employed 145.6 million people in 2016-17. This increased by 4 per cent to reach 151.8 million in 2020-21. While it constituted 36 per cent of all employment in 2016-17, the figure rose to 40 per cent in 2020-21, underlining the sector’s importance for the Indian economy. Employment in agriculture has been on the rise over the last two years with year-on-year (YoY) growth rates of 1.7 per cent in 2019-20 and 4.1 per cent in 2020-21.

119.7 million Indians were employed in the non-financial services in 2016-17 (excluding those in public administrative services and defense services) (Figure 3). This number rose by 6.7 per cent to reach 127.7 million in 2020-21. The financial services sector employed 5.3 million people in 2016-17 and this grew by 9 per cent to 5.8 million in 2020-21.

Public administrative services employed 9.8 million people in 2016-17 but it decreased by 19 per cent to 7.9 million in 2020-21.

In figure 4, we look at employment in manufacturing, real estate & construction, and mining sectors. Together these sectors accounted for 30 per cent of all employment in 2016-17 which came down to 21 per cent in 2020-21.

Manufacturing accounts for nearly 17 per cent of India’s GDP but the sector has seen employment decline sharply in the last 5 years. From employing 51 million Indians in 2016-17, employment in the sector declined by 46 per cent to reach 27.3 million in 2020-21. This indicates the severity of the employment crisis in India predating the pandemic.

On a YoY basis, it employed 32 per cent fewer people in 2020-21 over 2019-20. It had seen a growth of 1 per cent (YoY) in 2019-20. This has happened despite the Indian government’s push to improve manufacturing in the country with the ‘Make in India’ project. Under the project, India sought to create an additional 100 million manufacturing jobs in India by 2022 and to increase manufacturing’s contribution to GDP to 20 per cent by 2025.

Instead of increasing employment in the sector, we have seen a sharp decline over the last 5 years. When we look closely at industries that make the manufacturing sector, we find that this is a secular decline in employment across all sub-sectors, except chemical industries.

All sub-sectors within manufacturing registered a longer-term decline.

Dec 25, 2021

Riaz Haq

Riaz Haq has left a new comment on your post "India in Crisis: Unemployment and Hunger Persist After Waves of COVID":

Kaushik Basu

@kaushikcbasu

Latest cross-country labor force participation data. How did India get here? It has some of the world's best entrepreneurs, talented administrators & skilled workers. It is important not to be in data denial. Policy needs to be corrected & re-directed to the commoner's welfare.

https://twitter.com/kaushikcbasu/status/1474938472867766280?s=20

----------------

Labor Force Participation Rates:

India 46%

Pakistan 50%

Bangladesh 56%

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sl.tlf.cact.zs

Dec 25, 2021

Riaz Haq

India has spent a decade wasting the potential of its young #population. Once considered a formidable asset, #India’s #demographic bulge turned toxic due to the country’s lost economic decade! #unemployment #Modi #BJP #Hindutva https://qz.com/india/2104191/india-has-wasted-the-potential-of-its-...

For the better part of the past decade, India was touted as the next big economic growth story after China because of its relatively younger population. “Demographic dividend”—the potential resulting from a country’s working-age population being larger than its non-working-age population—was the key phrase.

Come 2022, the median age in India will be 28, well below 37 in China and the US.

Dec 26, 2021

Riaz Haq

The NMP is hardly the panacea for growth in India

https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-nmp-is-hardly-the-panace...

As the Government has also shown, there are out-of-the-box policy initiatives to revamp public sector businesses

The National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) envisages an aggregate monetisation potential of ₹6-lakh crore through the leasing of core assets of the Central government in sectors such as roads, railways, power, oil and gas pipelines, telecom, civil aviation, shipping ports and waterways, mining, food and public distribution, coal, housing and urban affairs, and stadiums and sports complexes, to name some sectors, over a four-year period (FY2022 to FY2025). But the point is that it only underscores the need for policy makers to investigate the key reasons and processes which led to once profit-making public sector assets becoming inefficient and sick businesses.

------------------

Congress leader Sachin Pilot on Wednesday slammed the Central government over National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) by saying that the new scheme will create monopoly and duopoly in the economy.

https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/nmp-will-...

Addressing a press conference in Bengaluru, Pilot questioned the government's decision to "lease core strategic assets of the country to private entities".

"The government said that NMP will get revenue of Rs 6 lakh crores for the next four years. The money that they will raise, will it go to fulfil the Rs 5.5 lakh crores deficit that we are running today or is it there to boost revenue," he stated.

"There is already a problem of unemployment in our country. When private entities take over the assets like railways, telecom and aviation, they will certainly lay off more people to make profits, which means more unemployment," he added.

Pilot further said that handing over important assets of the country to a handful of people will create a monopoly and duopoly in the economy.

The Congress MLA asserted that the NMP poses serious questions on the country's integrity and security. "I want to ask what stops the international funds to make an investment and take a stake in these important assets," he stated.

"There are many countries that forbid Chinese entities to bid for telecom tower or fibre optical cable. I want to question the government what safeguards have been placed in NMP to stop inappropriate entities from bidding for our core strategic assets," he added.

Pilot called the government's decision regarding NMP as 'unilateral' that happened without any discussion with trade unions, stakeholders or the Opposition. He further questioned the transparency of the whole process and how it is going to benefit people.

"Will the money raised be used to double farmers' income or to give Rs 15 lakhs to every Indian citizen as promised by the government? Or will it be used to make a building complex or in some vanity project," he questioned.

Dec 27, 2021

Riaz Haq

By Abhijit Banerjee, Nobel Laureate Economist

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/23/opinion/culture/holiday-feasting...

There’s a long tradition among social thinkers and policymakers of treating workers as walking, talking machines that turn calories into work and work into commodities that get sold on the market. Under capitalism, food is important because it provides fuel to the work force. In this line of thinking, enjoyment of food is at best a distraction and often a dangerous invitation to indolence.

The scolding American lawmakers who want to forbid the use of food stamps to purchase junk food are part of a long lineage that goes back to the Victorian workhouses, which made sure that the food was never inviting enough to encourage sloth. It is the continuing obsession with treating working-class people as efficient machines for turning nutrients into output that explains why so many governments insist on giving bags of grain to the poor instead of money that they might waste. This infantilizes the poor and, except in very special circumstances, it does nothing to improve nutrition.

The pleasure of eating, to say nothing of cooking, has no place in this narrative. And the idea that if working people knew what was good for them, they’d simply seek out more food as fuel is a woefully limited view of the eating experience of most of the world. As anybody who has been poor or has spent time with poor people knows, eating something special is a source of great excitement.

As it is for everyone. Standing at the end of this very dark and disappointing year, almost two years into a pandemic, we all need the joy of a feast — whether actual or metaphorical.

Every village has its feast days and its special festal foods. Somewhere goats will be slaughtered, somewhere ceremonial coconuts cracked. Perhaps fresh dates will be piled on special plates that come out once a year. Maybe mothers will pop sweetened balls of rice into the mouths of their children.

Friends and relatives will come over to help roast an entire camel for Eid; to share scoops of feijoada, that wonderful Brazilian stew of beans simmered with off-cuts, from pig’s ears to cow’s tongue; to pinch the dumplings for the Lunar New Year; to fold the delicate edges of sweet coconut-stuffed Maharashtrian karanji, to be fried under the watchful eye of the matriarch. The feast’s inspiration might be religious, but it could as well be a wedding, a birth, a funeral or a harvest.

-------

This feasting season, that momentary joy is likely to feel especially essential. Most of us have had reasons to worry — about ourselves, about our children and parents, about where the world is headed. This year many lost friends and relatives, jobs and businesses. Many spent months working in Zoom-land, languishing even as they counted themselves lucky to be employed.

Dec 27, 2021

Riaz Haq

#India's #economy growing fast but problems remain: November inflation 14.23%. #Fuel and #energy prices rose nearly 40% last month. Urban #unemployment – most of the better-paying jobs are in cities – has been moving up since September and is now above 9%. https://aje.io/ytyan4

That will not be easy, say experts. The pandemic has devastated India’s micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), which contribute 30 percent of the nation’s GDP as well as half of the country’s exports and represent 95 percent of its manufacturing units.

The government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi told Parliament in December that a survey it had conducted suggested that 9 percent of all MSMEs had shut down because of COVID-19. And that might be just the tip of the iceberg. In May, another survey of more than 6,000 MSMEs and startups found that 59 percent were planning to shut shop, scale down or sell before the end of 2021.

----------

Baldev Kumar threw his head back and laughed at the mention of India’s resurgent GDP growth. The country’s economy clocked an 8.4-percent uptick between July and September compared with the same period last year. India’s Home Minister Amit Shah has boasted that the country might emerge as the world’s fastest-growing economy in 2022.

Kumar could not care less.

As far as he was concerned, the crumpled receipt in his hand told a different story: The tomatoes, onions and okra he had just bought cost nearly twice as much as they did in early November. The 47-year-old mechanic had lost his job at the start of the pandemic. The auto parts store he then joined shut shop earlier this year. Now working at a car showroom in the Bengaluru neighbourhood of Domlur, he is worried he might soon be laid off as auto sales remain low across India.

He has put plans for his daughter’s wedding on hold, unsure whether he can foot the bill. He used to take a bus to work. Now he walks the five-kilometre (three-mile) distance to save a few rupees. “I don’t know which India that’s in,” he said, referring to the GDP figures. “The India I live in is struggling.”

Kumar wasn’t exaggerating – even if Shah’s prognosis turns out to be correct.

Asia’s third-largest economy is indeed growing again, and faster than most major nations. Its stock market indices, such as the Sensex and Nifty, are at levels that are significantly higher than at the start of 2021 – despite a stumble in recent weeks. But many economists are warning that these indicators, while welcome, mask a worrying challenge – some describe it as a crisis – that India confronts as it enters 2022.

November saw inflation rise by 14.23 percent, building on a pattern of double-digit increases that have hit India for several months now. Fuel and energy prices rose nearly 40 percent last month. Urban unemployment – most of the better-paying jobs are in cities – has been moving up since September and is now above 9 percent, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, an independent think-tank. “Inflation hits the poor the most,” said Jayati Ghosh, a leading development economist at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

All of this is impacting demand: Government data shows that private consumption between April and September of 2021 was 7.7 percent lower than in 2019-2020. The economic recovery from the pandemic has so far been driven by demand from well-to-do sections of Indian society, said Sabyasachi Kar, who holds the RBI Chair at the Institute of Economic Growth. “The real challenge will start in 2022,” he told Al Jazeera. “We’ll need demand from poorer sections of society to also pick up in order to sustain growth.”

Dec 28, 2021

Riaz Haq

Long #DoctorStrike over understaffing sparks chaos at #NewDelhi hospitals. While #India’s overall case count remains low, daily infections in the capital region have risen by more than 300% over the past two weeks. #OmicronInIndia #Omicron #Modi #COVID19 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/28/world/new-delhi-doctor-strike.ht...

Protests continued across the country and outside major hospitals in New Delhi on Tuesday, a day after police officers in the capital detained more than 2,500 protesting doctors who were walking toward the residence of India’s health minister.

--------

Medical students from across India have joined the protests, which intensified two weeks ago and have grown angrier after police officers were seen beating junior doctors during a march on Monday.

The New Delhi government has expressed concern over a rising number of coronavirus cases and announced new measures, including a nighttime curfew, to slow the spread of the virus. While the country’s overall case count remains low, daily infections in the capital region have risen by more than 300 percent over the past two weeks, according to the Our World in Data Project at the University of Oxford. It is unclear how many of the new cases are of the Omicron variant.

As the doctors’ strike has stretched on, drawing in recent graduates and tens of thousands of the more than 70,000 doctors who work at government medical facilities nationwide, emergency health services have been the worst hit.

Videos from major state-run hospitals in New Delhi have shown patients on stretchers lying unattended outside emergency rooms. Many Indians rely on state medical facilities for care because of the high cost of treatment at private hospitals.

The protests were triggered by delays in placing medical school graduates in jobs at government health facilities, as India’s Supreme Court considers an affirmative action policy aimed at increasing the share of positions reserved for underrepresented communities. Protesting doctors say they are not against the quotas, but want the court to expedite its decision so that graduates can begin their jobs.

During India’s catastrophic coronavirus wave earlier this year, doctors and other medical personnel found themselves short-handed and underfunded as they battled an outbreak that at its height was causing 4,000 deaths a day. Doctors associations say that more 1,500 doctors have died from Covid since the pandemic began.

Dec 28, 2021

Riaz Haq

#India was slow to identify and publicize the emergence of #DeltaVariant, setting off deadly global resurgence of #COVID19 that took millions of lives. #Modi #BJP #Hindutva #Islamophobia https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-12-29/how-delta-varian...

Unknown at the time, Amravati’s flare-ups were the first visible warning that the SARS-CoV-2 variant now known as delta had started along its devastating path. Within weeks, thousands of people flooded Amravati’s underfunded healthcare network as the city turned into Ground Zero for what would become the most confounding version of the pathogen first identified in Wuhan, China a year earlier.

Amravati was a precursor to the horrors that would grip all of India, and spread globally. As January drew to a close, Bhushan was already sensing that the city of more than 600,000 residents was becoming a petri-dish for a form of Covid-19 his team hadn’t treated before. Earlier, patients’ symptoms improved in under two weeks, but now they were battling the virus for “almost 20 to 25 days,” he said. “It was a nightmarish situation.”

Despite those first, ominous signs, what followed goes some ways toward explaining why two years into this pandemic, the world remains on the brink of economy-shattering shutdowns, with another new variant emerging out of vulnerable, under-vaccinated populations. But while South Africa acted swiftly last month to decode the heavily mutated omicron and publicize its existence, India’s experience perhaps better reflects the reality faced by most developing countries – and the risks they potentially pose.

India’s hampered response was characterized by months of inertia from the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and a startling lack of resources, according to interviews with two dozen scientists, officials, diplomats and health workers. Many asked not to be identified because they aren’t authorized to speak to the media or were concerned about talking publicly about India’s missteps.

The actions India did — and didn’t take — as delta emerged, ultimately saddled its people and the world with a ruthlessly virulent incarnation of the coronavirus, one that challenged vaccines and containment regimes like none before it. Delta upended even the most successful pandemic strategies, snaking into countries like Australia and China with stringent “Covid Zero” curbs in place and effectively closed borders. It’s been the most dominant form of Covid for much of this year, when more than 3.5 million people died of the virus — almost double the toll during the first year of the pandemic.

Multiple scientists interviewed by Bloomberg News said that the way India handled the early days of delta fueled its rise. The variant’s identification was delayed because the country’s laboratories were flying blind for much of 2020 and early 2021, partly because Modi’s government had restricted imports of vital genetic sequencing compounds under a nationalistic agenda to drive self sufficiency, they said. There were repeated efforts to warn the administration about the new strain in early February, the scientists said, yet India went public with details of the more transmissible variant only at the end of March.

Dec 29, 2021

Riaz Haq

#India's staggering COVID-19 death toll could be 6 million, by far the highest #COVID19 death toll in the world -- greater than the #US at more than 811,000. #Modi #BJP #pandemic #Delta #OmicronVariant - ABC News - https://abcn.ws/30UZSLO via @ABC

Even though omicron is quickly becoming the more dominant form of Covid in the U.S. and elsewhere, quick action has bought time for scientists to decode the extent of its transmissibility and severity. South Africa identified and broadcast details of the new variant just weeks after seeing a spike in cases in one province.

By contrast, for much of 2020, India’s efforts tracking the virus were sparse, meaning the exact origin of delta still remains murky. To date, the country has only sequenced and shared 0.3% of its total official infections to the GISAID database.

India has been held back by the fact that only a handful of government laboratories and states were making consistent efforts in the first year of the pandemic to map the virus, even as millions were being infected in the country’s first wave, according to people familiar with the matter. Bhramar Mukherjee, an epidemiologist and biostatistics chair at the University of Michigan's School of Public Health, said India’s sequencing efforts were hurt by “bureaucracy, politics and a sense of exceptionalism that we have conquered Covid and there is no need to worry about variants.”

“The need to share data and samples is so key,” she said. “When South Africa started collaborating and sharing with the rest of the world, progress also increased like a process of contagion: exponentially. India is always protective of its own data.”

Inside India’s scientific agencies a lack of institutional dynamism, along with a culture of subservience to Modi’s government — highly sensitive to commentary on its handling of the virus — had taken hold, said one former official. That meant critical questions weren’t being aired by experts out of fear they’d derail their careers, the person said. In many cases, India’s health ministry simply wasn’t listening to or making decisions based on advice coming from those expert bodies, according to this official.

Attempts to ramp up sequencing in India were also critically curtailed by an inadvertent ban in May 2020 on the import of reagents, the chemical needed to fuel sequencer machines. The `Make in India’ campaign, Modi’s drive to ensure the country is less reliant on places like China, meant publicly-financed labs weren’t able to import items worth less than 2 billion rupees ($26.5 million) for months. India mostly uses sequencers manufactured by San Diego-based Illumina Inc. and the U.K.’s Oxford Nanopore Technologies Plc, which run on patented reagents that can’t be substituted locally.

Scientists in India and abroad now provide varying dates for when delta began circulating there. Samples retrospectively added to GISAID show at least one delta-linked lineage in India as far back as September last year, while the World Health Organization places its first discovery there in October.

Current and former Indian government scientists say there are often errors when manually uploading information to the database and those datelines are likely to be wrong. December 2020 is when delta was initially sequenced in India, they say. Certainly, the first person to decode the mutations wouldn’t have known its full enormity at the time since not all changes in a virus are significant. Only when you begin to see spiraling outbreaks marked by similar characteristics do you realize that a variant of concern is at play, they said. But Amravati offered the clues needed to make that connection as early as January this year.

Dec 29, 2021

Riaz Haq

#India's year 2021 ended with worse #unemployment rate than it began. The year 2021 is closing with an unemployment rate of 8.01% in Dec vs 6.52% in January, according to @_CMIE. It's worsened even before #COVID19 #OmicronVarient appeared. #Modi #BJP https://www.thenorthlines.com/year-ends-with-worse-unemployment-rat...

The year 2021 is closing with an unemployment rate of 8.01 per cent in India as against 6.52 per cent in January. It is a great cause of frustration. In January, unemployment rate in the urban area was 8.09 per cent which was up on December 30 at 9.26 per cent, and for rural areas it was up at 7.44 per cent as against only 5.81 per cent. It all indicates a great labour market distortion despite a trend in the economic recovery in both urban and rural areas.

Unemployment has worsened at a time when a new Omicron variant of COVID-19 is spreading like wildfire both in India and several other countries, enforcing lockdowns and containment measures. There is great uncertainty in the labour market, and nobody knows what will happen next, chiefly because Omicron overrides immunity from vaccination. The year 2022 is thus opening with a gloom scenario, as against 2021 which had begun with a hope after a miraculous development of vaccines and rollout from January 16. It was hoped that market conditions would improve enabling unemployed to get employment.

Unemployment rate in December 2020 was 9.06 per cent. For urban areas it was even higher at 9.15 per cent. At that time the urban unemployment rate was 8.84. All India unemployment rate then began improving with the opening of almost all sectors of economy. By March it fell to 6.50 per cent which is the lowest for this year, with urban unemployment at 7.27 per cent and rural unemployment at 6.15 per cent. However, it was worse than the unemployment rate of 6.1 per cent in the beginning of 2018, which was at 45 years high for the country.

The situation had started worsening sharply from November 2016 after Modi’s demonetisation order which forced cores of business and industrial establishments, especially MSMEs to close. Millions others struggled to survive due to shortage of cash, and millions more cut their production up to 75 per cent. Crores of people lost their jobs and by the beginning of 2018, unemployment in India was 45 year high. Unemployed were thus hit hardest in the Modi rule, which the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic made even worse. Lockdown order of March 24, 2020 put brake on the whole economy to a grinding halt, which began to open from June 1, 2020 in phased manner.

The country was hit by the second wave of COVID-19 in April, which necessitated further lockdowns and containment measures. Labour market suddenly deteriorated and the gains of the last three months were reversed. Unemployment rate rose to 7.97 per cent from 6.50 per cent just a month ago. Both the urban and rural areas were adversely affected and the unemployment rate rose to 9.78 and 7.13 per cent respectively.

May proved to be worst with the rise in the ferocity of the second wave. Markets were shut down and millions of establishments closed. Unemployment rate shot up to 11.84 per cent which is highest for the current year. Unemployment in the urban areas became even worse at 14.72 per cent while in the urban areas it was 10.55 per cent.

Jan 1, 2022

Riaz Haq

#India reports first death linked to #Omicron #coronavirus variant.the western state of #Rajasthan. Omicron cases in the country have now risen to 2,135, #Indian #health official told a small group of reporters in #NewDelhi. #Pandemic #BJP #Modi #Covid_19 https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-reports-first-death-linke...

India on Wednesday reported its first COVID-19 death linked to the fast-spreading Omicron variant in the western state of Rajasthan, a federal health ministry official said.

Omicron cases in the country have now risen to 2,135, the official told a small group of reporters in New Delhi.

Jan 5, 2022

Riaz Haq

India will likely get old before it gets rich

By Mihir Sharma

https://www.livemint.com/economy/india-seems-likely-to-grow-old-bef...

By the middle of this century, India will have 1.6 billion people. That’s when the country’s population will finally start to decline, ending up at perhaps a billion by 2100. While that is still around 250 million more people than China will have then, every time India’s population is projected, its peak seems to come earlier and crest lower. While India will be a young country for decades yet, it is ageing faster than expected. The latest round of India’s massive National Family Health Survey (NFHS) underscores the point. The average Indian woman is now likely to have only two children. That’s below the “replacement rate" of 2.1, at which the population would exactly replace itself over generations.

A few decades ago, this would have been considered miraculous in a country dismissed as a Malthusian nightmare. As modern health care became increasingly available after independence in 1947, population growth exploded—rising from 1.26% annually in the 1940s to 2% in the 1960s. Twenty years after independence, the demographer Sripati Chandrashekhar became India’s health minister and warned that “the greatest obstacle in the path of overall economic development is the alarming rate of population growth." The India in which I grew up was plastered with the inverted red triangle of the government’s family planning campaign.

As it turned out, increasing prosperity, decreases in infant mortality and—crucially—female education and empowerment achieved more than government propaganda ever could. In urban India, the fertility rate is now 1.6, according to the NFHS, equivalent to that of the US.

This is good news. But unalloyed good news is rare in India and this is no exception. The unexpected speed of the demographic transition has forced India to confront a new problem.

China-watchers have long debated whether that country will grow old before it gets rich. India now has to answer that same question, with far fewer resources at its disposal.

Draconian though China’s one-child policy was, those born under it received unprecedented attention from their families: Average education levels rose sharply, as did the quality of their nutrition. In India, by contrast, the NFHS shows that not only is child malnutrition high, it is not improving fast enough. In fact, in the five years after 2015-16, acute undernourishment actually worsened for children in most parts of India.

Meanwhile, India’s education system is clearly failing. Indian companies are already reporting a shortage of skilled manpower. That isn’t because schools aren’t turning out enough graduates. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy reports the unemployment rate for college graduates is 19.3%, almost three times higher than the national average. Universities just aren’t producing the kind of workers that companies feel they can employ. In some large-scale surveys, employers have said that less than half the college graduates entering the workforce have the cutting-edge skills they need or the ability to pick them up in the workplace.

Moreover, too few of these young people are trying to get into the workplace at all. Two-thirds of working-age Chinese are currently either employed or looking for a job, according to the International Labour Organization; at the beginning of the country’s high-growth spurt in the early 2000s, this labour force participation rate hit 80%. (The global average is close to 60%.) In India, by contrast, CMIE estimates that the country’s LPR stands at a mere 43% and that the pandemic has “lowered the LPR structurally" to 40%. One big reason: Just one in five Indian women work, which the World Bank has argued is linked to the social stigma of holding jobs outside the home.

Jan 6, 2022

Riaz Haq

‘It’s a total disaster’: #Omicron lays waste to #India’s huge #weddingseason. Distraught couples face prospect of cutting guest lists from more than 600 people down to just 20 after #coronavirus variant took hold. #COVID19 #pandemic #economy https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/18/its-a-total-disaster-...

India has enjoyed a halcyon period since June. As late as November, the capital of 20 million people was recording a mere 35-45 fresh infections a day. But with Omicron fuelling a sudden surge the government has re-imposed restrictions. India is recording around 258,000 cases daily nationally, with New Delhi recording 18,286 cases on Sunday.

Sahiba Puri, of XO Catering by Design in Delhi, understands the need for the restrictions but has no idea what to do with the cooks who have flown in from different parts of India for a pre-wedding function at the weekend.

“The bride’s family wanted to treat guests to all kinds of regional cuisines so these cooks have come and have bought so many of the ingredients. Where do they go? They are paying rent for where they are staying and other expenses,” says Puri.

With the industry staring at yet another disaster, Mishra and others plan to ask the government to relax the 20-guest rule. The Confederation of All India Traders has also written to the government asking for a relaxation.

However, given the current explosion in cases, any relaxation is unlikely. Wedding card printer Arnav Gupta says: “Everyone is so haunted by the brutal second wave that no politician is going to take any chances.”

Vashisht has decided she cannot uninvite 630 guests. She has no choice but to postpone, but planning a later date is proving impossible too. “Who knows when this wave will end? It’s only just got going. Do I tentatively look at a date in March? April? May? I mean, who knows? This limbo is killing me.”

Jan 17, 2022

Riaz Haq

Has India lost its demographic sweet spot?

N Madhavan| Updated On: Jan 20, 2022

https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/has-india-lost-its-dem...

Acclaimed author and investor Ruchir Sharma, while delivering the 40th Palkhivala Memorial Lecture earlier this week, called upon Indian economists to shed their “anchoring bias” and stop talking about 8-9 per cent GDP growth which is difficult to achieve.

He blamed four trends for his view. India, he said, has lost its demographic sweet spot. The country’s working age population growth rate which was more than 2 per cent till 2010 has dropped to 1.5 per cent. He quoted his research to say that 75 per cent of the countries with economic growth of 6 per cent or more had a working age population growth in excess of 2 per cent. Most developed nations slowed down as their working age population dropped. The current population growth rate in India is not conducive for high economic growth, he warned.

Pandemic and indebtedness

The challenges created by declining demography is further accentuated by declining productivity (these two factors are the major drivers of economic growth). He argues that all the recent technological innovations have been more on the consumer experience side and they have not resulted in increasing productivity. The pandemic, he added, has pushed nations deeper into debt.

The amount of debt in the world today is 4X the size of the global economy with 25 countries having a debt/GDP ratio in excess of 300 per cent. India’s level of debt (170 per cent of GDP), while lower compared to other nations, is high when one considers its per capita income. High debt cuts productivity and smothers growth, he said.

The final trend that forced him to come out with this stark prognosis for the Indian economy is de-globalisation. Post world War-II, there was intense globalisation where flow of trade, people and capital exploded. Countries that were growing their economy in excess of 6 per cent registered exports growth of 20 per cent or more. After the global financial crisis, protectionism has increased. This has caused trade in goods and services to plateau. Capital flows have also dropped. Without strong exports, high growth rates are not possible for any country, including India.

Growth reset

He concluded by saying that for India any economic growth in excess of 5 per cent should be a great achievement. If what he says comes true, India’s ambition of becoming a higher middle income country like China (for that it needs to grow its per capita income at 8.8 per cent for the next 10 years) or a developed nation like US (it needs to grow at a rapid pace for many decades) will not happen.

The country will not be able to pull its poor out of poverty and significantly increase its per capita income which is currently a little less than $2,000 (China’s, in comparison, is in excess of $12,000).

But has Ruchir Sharma extrapolated what a slowing population growth did to developed nations to India without considering its uniqueness? That appears to be the case. While it is true that India’s total fertility rate fell to 2.0 per cent -- below the replacement rate of 2.1 per cent -- in the recent National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), the population (according to a paper prepared by C Rangarajan, former RBI Governor, and JK Satia, Prof Emeritus, Indian Institute of Public Health) will continue to grow and will peak at 165 crore only around 2050.

The paper attributes this to population momentum arising out of a larger number of people entering reproductive age group of 15-49 compared to those leaving it. So reduction in working age population is not going to be sharp and immediate.

Jan 21, 2022

Riaz Haq

No labour shortage

Also, India is not a labour scarce country. The US saw its labour rates rise rather sharply when population growth slowed. It was forced to outsource production to China to remain competitive. While there is a mis-match between availability of labour and nature of the available jobs, India is not short of hands. This problem can be resolved, in the short run, through re-skilling programmes and in the long run through adequate investment in the education sector.

Unlike developed economies, India also has a large headroom for improvement -– be it labour participation (a large proportion of women are still outside the labour force), labour productivity (existing people can be pushed to produce a lot more), infrastructure efficiency and adoption of technology.

At the same time, the government should not ignore what Sharma is saying. It should act now and doing so will help the country to be better prepared to tackle the challenges demographic changes will bring about tomorrow.

Need for skills upgrade

There is an urgent need to map skill requirements of the future and ensure that the education system is tuned to deliver them. Mere large scale investment in education, though needed, will not be enough. Similarly, a conscious strategy needs to be devised on use of technology in a manner that it adds value and improves productivity without causing significant job losses.

The government should also eschew protectionist tendencies that has gripped the world. It should be flexible and strike preferential trade deals that are overall beneficial to India. Exports may not be as critical for India as it is for countries like China or Japan and it is unlikely to become so in the future as its economy will continue to be powered by domestic consumption. Still, exports have their benefits. It contributes to economic growth, funds imports, improves efficiency and helps to keep the current account deficit in check. Strong exports growth is a pre-requisite for a fast paced economic growth.

There is also a need for a single-minded focus on economic growth. The government should avoid all distractions, domestic or foreign, in order to achieve this. China did just that till its economy reached a significant size. It is different story that it is throwing its weight around in geo-politics today.

A growth focussed prudent economic policy will ensure that India’s investment rate which has fallen significantly since 2007-08 will bounce back. Once that happens, high growth rate will return and India will be in a position to take advantage of the demographic dividend before it is too late.

Jan 21, 2022

Riaz Haq

India's economy has some bright spots, a number of very dark stains: Raghuram RajanRajan said that one way to expand budgetary resources is through asset sales, including parts of government enterprises and surplus government land

Read more at: https://www.deccanherald.com/national/indias-economy-has-some-brigh...

The Indian economy has "some bright spots and a number of very dark stains" and the government should target its spending "carefully" so that there are no huge deficits, noted economist and former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan said on Sunday. Known for his frank views, Rajan also said the government needs to do more to prevent a K-shaped recovery of the economy hit by the coronavirus pandemic. Generally, a K-shaped recovery will reflect a situation where technology and large capital firms recover at a far faster rate than small businesses and industries that have been significantly impacted by the pandemic. "My greater worry about the economy is the scarring to the middle class, the small and medium sector, and our children's minds, all of which will come into play after an initial rebound due to pent up demand. One symptom of all this is weak consumption growth, especially for mass consumption goods," Rajan told PTI in an e-mail interview.

Rajan, currently a Professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, noted that as always, the economy has some bright spots and a number of very dark stains. "The bright spots are the health of large firms, the roaring business the IT and IT-enabled sectors are doing, including the emergence of unicorns in a number of areas, and the strength of some parts of the financial sector," he said. On the other hand, "dark stains" are the extent of unemployment and low buying power, especially amongst the lower middle-class, the financial stress small and medium-sized firms are experiencing, "including the very tepid credit growth, and the tragic state of our schooling". Rajan opined that Omicron is a setback, both medically and in terms of economic activity but cautioned the government on the possibility of a K-shaped economic recovery. "We need to do more to prevent a K shaped recovery, as well as a possible lowering of our medium-term growth potential," he said.

--------

Regarding the rising inflationary trends, Rajan said inflation is a concern in every country, and it would be hard for India to be an exception. According to him, announcing a credible target for the country's consolidated debt over the next five years coupled with the setting up of an independent fiscal council to opine on the quality of the budget would be very useful steps. "If these moves are seen as credible, the debt markets may be willing to accept a higher temporary deficit," he said.

Jan 23, 2022

Riaz Haq

#Modi’s #India: #Income of the poorest 20% #Indians plunged 53% in 5 yrs while the richest 20% saw their annual household income grow 39%. #Inequality #BJP #Hindutva #Covid | India News,The Indian Express

https://indianexpress.com/article/india/income-of-poorest-fifth-plu...

In a trend unprecedented since economic liberalisation, the annual income of the poorest 20% of Indian households, constantly rising since 1995, plunged 53% in the pandemic year 2020-21 from their levels in 2015-16. In the same five-year period, the richest 20% saw their annual household income grow 39% reflecting the sharp contrast Covid’s economic impact has had on the bottom of the pyramid and the top.

This stark K-shaped recovery emerges in the latest round of ICE360 Survey 2021, conducted by People’s Research on India’s Consumer Economy (PRICE), a Mumbai- based think-tank.

The survey, between April and October 2021, covered 200,000 households in the first round and 42,000 households in the second round. It was spread over 120 towns and 800 villages across 100 districts.

While the pandemic brought economic activity to a standstill for at least two quarters in 2020-21 and resulted in a 7.3% contraction in GDP in 2020-21, the survey shows that the pandemic hit the urban poor most and eroded their household income.

Splitting the population across five categories based on income, the survey shows that while the poorest 20% (first quintile) witnessed the biggest erosion of 53%, the second lowest quintile (lower middle category), too, witnessed a decline in their household income of 32% in the same period. While the quantum of erosion reduced to 9% for those in the middle income category, the top two quintiles — upper middle (20%) and richest (20%)— saw their household income rise by 7% and 39% respectively.

The survey shows that the richest 20% of households have, on average, added more income per household and more pooled income as a group in the past five years than in any five-year period earlier since liberalisation. Exactly the opposite has happened for the poorest 20% of households — on average, they have never actually seen a decrease in household income since 1995. Yet, in 2021, in a huge knockout punch caused by Covid, they earned half as much as they did in 2016.

How disruptive this distress has been for those at the bottom of the pyramid is reinforced by the fact that in the previous 11-year period between 2005 and 2016, while the household income of the richest 20% grew by 34%, the poorest 20% saw their household income surge by 183% at an average annual growth rate of 9.9%.

Coming in the run-up to the Budget, the task for the Government is cut out.

“As the Finance Minister is finalising her budget proposals for 2022-23 to give shape to the roadmap for economic revival of the country,” said Rajesh Shukla, MD and CEO, PRICE, “we need a K-shaped policy too that addresses the two ends of the spectrum and a lot more thinking on how to build the bridge between the two.”

This couldn’t be more timely. Said PRICE founder and one of the authors of the survey Rama Bijapurkar. “Or else, we are back to a tale of two Indias, a narrative we thought we were rapidly getting rid of. The good news is that we have built a far more efficient welfare state for the disbursal of benefit be it DBT or vaccination for all.”

The survey showed that while the richest 20% accounted for 50.2% of the total household income in 1995, their share has jumped to 56.3% in 2021. On the other hand, the share of the poorest 20% dropped from 5.9% to 3.3% in the same period.

As for India Inc, it has been in a better position to weather the disruption. The pandemic accelerated further formalisation of the economy with large companies benefitting at the cost of smaller ones. The survey also shows that while job losses were quite evident among Small and Medium Enterprises in the casual labour segment, large companies did not witness much of that.

Jan 23, 2022

Riaz Haq

#Modi’s #India: #Income of the poorest 20% #Indians plunged 53% in 5 yrs while the richest 20% saw their annual household income grow 39%. #Inequality #BJP #Hindutva #Covid | India News,The Indian Express

https://indianexpress.com/article/india/income-of-poorest-fifth-plu...

Even among the poorest 20 per cent, those in urban areas got more impacted than their rural counterparts as the first wave of Covid and the lockdown led to stringent curbs on economic activity in urban areas. This resulted in job losses and loss of income for the casual labour, petty traders household workers.

Data shows that there has been a rise in the share of poor in cities. While 90 per cent of the poorest 20 per cent in 2016, lived in rural India, that number had dropped to 70 per cent in 2021. On the other hand the share of poorest 20 per cent in urban areas has gone up from around 10 per cent to 30 per cent now.

“The data reflects that the casual labour, petty trader, household workers among others in Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities got hit most by the pandemic. During the survey we also noticed that while in rural areas people in lower middle income category (Q2) have moved to middle income category (Q3), in the urban areas the shift has been downwards from Q3 to Q2. In fact, the rise in poverty level of urban poor has pulled down the household income of the entire category down,” said Shukla.

“The elephant in the room is investment,” said Bijapurkar. “Inspiring confidence through long-term policy stability and improving ease of doing business should make the tide rise again and sweep small business and individuals up along with it. Most big companies are doing well and don’t need more help but we need to work the economy for the bottom half.”

Jan 23, 2022

Riaz Haq

#India's #jobs crisis exasperates its youth. #Economic growth is producing fewer jobs than it used to, and disheartened jobseekers instead take menial roles or look to move overseas. #BJP #economy #Modi #unemployment https://news.yahoo.com/off-canada-indias-jobs-crisis-052922928.html... via @YahooNews

RAJPURA, India (Reuters) - Srijan Upadhyay supplied fried snacks to small eateries and roadside stalls in the poor eastern Indian state of Bihar before COVID-19 lockdowns forced most of his customers to close down, many without paying what they owed him.

With his business crippled, the 31-year-old IT undergraduate this month travelled to Rajpura town in Punjab state to meet with consultants who promised him a work visa for Canada. He brought along his neighbour who also wants a Canadian visa because his commerce degree has not helped him get a job.

"There are not enough jobs for us here, and whenever government vacancies come up, we hear of cheating, leaking of test papers," Upadhyay said, waiting in the lounge of Blue Line consultants. "I am sure we will get a job in Canada, whatever it is initially."

India's unemployment is estimated to have exceeded the global rate in five of the last six years, data from Mumbai-based the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) and International Labour Organization show, due to an economic slowdown that was exacerbated by the pandemic.

Having peaked at 23.5% in April 2020, India's joblessness rate dropped to 7.9% last month, according to CMIE.

The rate in Canada fell to a multi-month-low of 5.9% in December, while the OECD group of mostly rich countries reported a sixth straight month of decline in October, with countries including the United States suffering labour shortages as economic activity picks up.

Graphic: Unemployment Rate- https://graphics.reuters.com/INDIA-UNEMPLOYMENT/INDIA/zjvqknbzxvx/c...

What's worse for India, its economic growth is producing fewer jobs than it used to, and as disheartened jobseekers instead take menial roles or look to move overseas, the country's already low rate of workforce participation - those aged 15 and above in work or looking for it - is falling.

"The situation is worse than what the unemployment rate shows," CMIE Managing Director Mahesh Vyas told Reuters. "The unemployment rate only measures the proportion who do not find jobs of those who are actively seeking jobs. The problem is the proportion seeking jobs itself is shrinking."

Graphic: Labour participation rate (LPR)- https://graphics.reuters.com/INDIA-UNEMPLOYMENT/INDIA-UNEMPLOYMENT/...

Critics say such hopelessness among India's youth is one of the biggest failures of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who first came to power in 2014 with his as yet unfulfilled promise of creating millions of jobs.

It also risks India wasting its demographic advantage of having more than two-thirds of its 1.35 billion people of working age https://data.oecd.org/pop/working-age-population.htm.

The ministries of labour and finance did not respond to requests for comment. The labour ministry's career website had more than 13 million active jobseekers as of last month, with only 220,000 vacancies.

The ministry told parliament in December that "employment generation coupled with improving employability is the priority of the government", highlighting its focus on small businesses.

Modi's rivals are now trying to tap into the crisis ahead of elections in five states, including Punjab and most populous Uttar Pradesh, in February and March.

"Because of a lack of employment opportunities here, every kid looks at Canada. Parents hope to somehow send their kids to Canada," Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, whose Aam Admi Party is a front-runner in Punjab elections, told a recent public function there.

Jan 25, 2022

Riaz Haq

#India #Jobs Crisis: At least 10 million applicants were hoping to get the roughly 40,000 jobs. Jobless mob set fire to #Indian #Railway trains. #RailwaysProtest #BJP #Modi #Bihar #UP #Hindutva #Islamophobia #unemployed #Unemployment https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/protests-over-railway-job...

The protests over problems with recruitment for railway jobs in the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, may well be India’s first large-scale unemployment riots. The protests have taken place across a large number of places in these two states. News reports suggest that at least 10 million applicants were hoping to get the roughly 40,000 jobs which were on offer. The politics on the protests notwithstanding – opposition parties have attacked the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) over both the issue and police’s handling of it – they ought to be treated as a bellwether for the socio-economic unrest which India’s job markets can generate. Here are four charts which put this in perspective.

India has among the worst labour market outcomes for young people

An international comparison of some of India’s peers and neighbours using World Bank data shows that India has among the worst labour market outcomes for the young (the 15-24-year-old population). This can be seen in persistence of high youth unemployment rates despite a very low labour force participation rate (LPFR) among this cohort. LPFR is defined as the share of economically active population – either working or looking for a job – in the given age group. This number was just 27.1% for the 15-24-year-old population in India, which is significantly lower than other countries. Despite such a low LFPR, youth unemployment rate is among the highest in India. Unemployment rate is defined as the share of unemployed persons in the labour force. A time-series analysis shows that things have become worse on this front in India in the last 15 years.

Jan 28, 2022

Riaz Haq

Millions of #Indian workers fled to villages amid #COVID #pandemic. Number of people working in #manufacturing fell by half over 4 years ending in March 2021. Around 75 million people in #India slipped into extreme #poverty. #Modi #unemployment https://www.wsj.com/articles/indias-economy-hinges-on-the-return-of... via @WSJ

The nationwide lockdown in 2020 set off the biggest wave of migration since India gained independence in 1947. In the first months of the pandemic, workers traveled hundreds of miles by train, bus, bicycle and even on foot.

While some returned to the cities at various points during the pandemic, another deadly Covid-19 surge last spring, and the most recent spike, have caused further uncertainty among workers about the costs of urban life.

Economists calculate that around 32 million people took up agricultural work in the year that ended on June 30, 2020, an estimate based on government data. That continued last year, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt., CMIE, an independent think tank in Mumbai. The share of agriculture in total employment in the year ended June 30, 2021, rose 1.4 percentage point from a year earlier, according to its data.

Some economists believe workers will return en masse after the pandemic subsides. “Agriculture can’t support so many people for so long,” said Sachchidanand Shukla, chief economist at the Mahindra Group, a conglomerate that includes businesses in information technology and vehicle manufacturing.

Mr. Nayal, the former call-center worker, isn’t sure of that. He lives in Satbunga, a village of about 1,400 people who live and work on land spread across mountain slopes.

The village head, Priyanka Bisht, estimated about 250 mostly men left for jobs in the city over the past five years. Most have returned, she said, bringing new skills and experience that benefit Satbunga. Ms. Bisht said she believed most prefer to stay, but added, “Let’s wait and watch how it turns out.”

---------

The number of people working in manufacturing has fallen by half over the four years that ended in March 2021, according to an analysis by Ashoka University’s Centre for Economic Data and Analysis based on CMIE data. “The decade that just went by, it can be called a decade of job loss,” said Kunal Kumar Kundu, an India economist at French bank Société Générale SA . “That is disastrous for an economy.”

India’s Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said a recently announced government program to boost domestic manufacturing will create millions of jobs.

About half of India’s working-age population is employed or seeking work, one of the world’s lowest labor-force participation rates, according to the ILO. Adding to the job squeeze, an estimated four million-plus young people join the workforce each year.

Feb 13, 2022

Riaz Haq

State of

Global Hiring

Report 2021

https://f.hubspotusercontent30.net/hubfs/19498232/State%20of%20hiri...

Salaries are rising fastest in Mexico (57%), Canada (38%), Pakistan (27%), and Argentina (21%) for jobs in marketing, sales, and product.

India 8%, Philippines 7% & Russia 4%

----------------

Top three countries where people hired through Deel were located:

1.Philippines 2. India 3. Pakistan

---------------

Top 3 roles hired through deel:

1. Software engineer 2. Virtual assistant 3. Custom Support Executive

------

State of Global Hiring

Report 2021

Global hiring has never been more popular

between pandemic-related office closures,

fierce talent competition, and a bevy of online

tools enabling collaboration and reducing

hiring complications. But where is it popular,

and for what roles? What countries are hiring

more than ever, and from where? What’s

happening to wages as demand increases?

Using data pulled from more than 100,000 work contracts from

over 150 countries, along with 500,000 third-party data points,

a new report from global hiring and payroll company Deel gives a

breakdown of what’s happening within the global job landscape.

Trends are tracked over six months—from July 2021 through December 2021.

Feb 15, 2022

Riaz Haq

#Unemployment Crisis in #Modi's #India: This burning train is a symbol of the anger of India's out-of-work youth. #Indian #economy has slowed down since 2010. Consequently, the pace of #job creation has been on a steady decline since 2011. #BJP #Hindutva https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2022/03/16/1084139074/thi...