PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and 3.5 million entrepreneurs in November alone. Many among the unemployed can no longer afford to buy food, causing a significant spike in hunger. The country's economy is finding it hard to recover from COVID waves and lockdowns, according to data from multiple sources. At the same time, the Indian government has reported an 8.4% jump in economic growth in the July-to-September period compared with a contraction of 7.4% for the same period a year earlier. This raises the following questions: Has India had jobless growth? Or its GDP figures are fudged? If the Indian economy fails to deliver for the common man, will Prime Minister Narendra Modi step up his anti-Pakistan and anti-Muslim rhetoric to maintain his popularity among Hindus?

|

| Labor Participation Rate in India. Source: CMIE |

Unemployment Crisis:

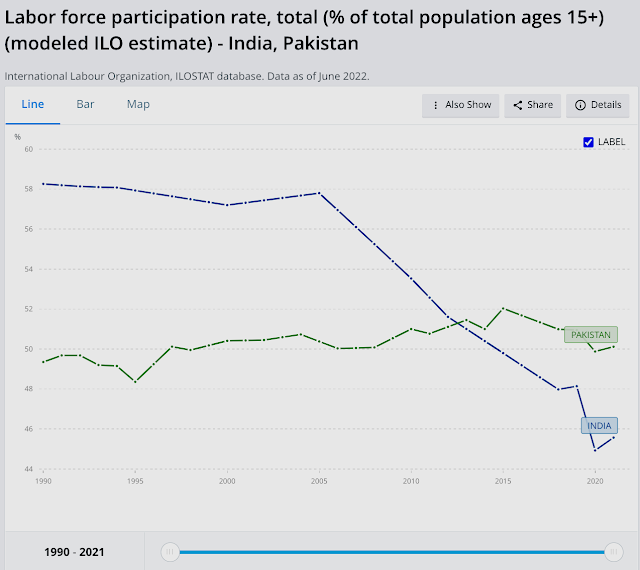

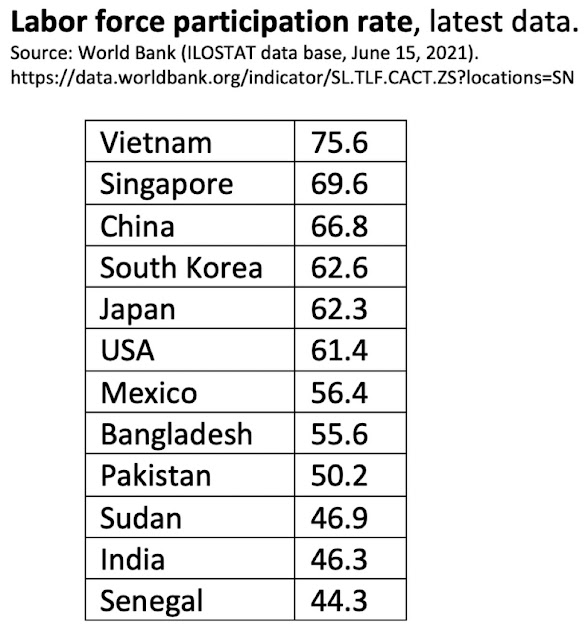

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and its labor participation rate (LPR) slipped from 40.41% to 40.15% in November, 2021, according to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). In addition to the loss of salaried jobs, the number of entrepreneurs in India declined by 3.5 million. India's labor participation rate of 40.15% is lower than Pakistan's 48%. Here's an except of the latest CMIE report:

"India’s LPR is much lower than global levels. According to the World Bank, the modelled ILO estimate for the world in 2020 was 58.6 per cent (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.ZS). The same model places India’s LPR at 46 per cent. India is a large country and its low LPR drags down the world LPR as well. Implicitly, most other countries have a much higher LPR than the world average. According to the World Bank’s modelled ILO estimates, there are only 17 countries worse than India on LPR. Most of these are middle-eastern countries. These are countries such as Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Syria, Senegal and Lebanon. Some of these countries are oil-rich and others are unfortunately mired in civil strife. India neither has the privileges of oil-rich countries nor the civil disturbances that could keep the LPR low. Yet, it suffers an LPR that is as low as seen in these countries".

|

| Labor Participation Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: World Bank/ILO |

|

| Labor Participation Rates for Selected Nations. Source: World Bank/ILO |

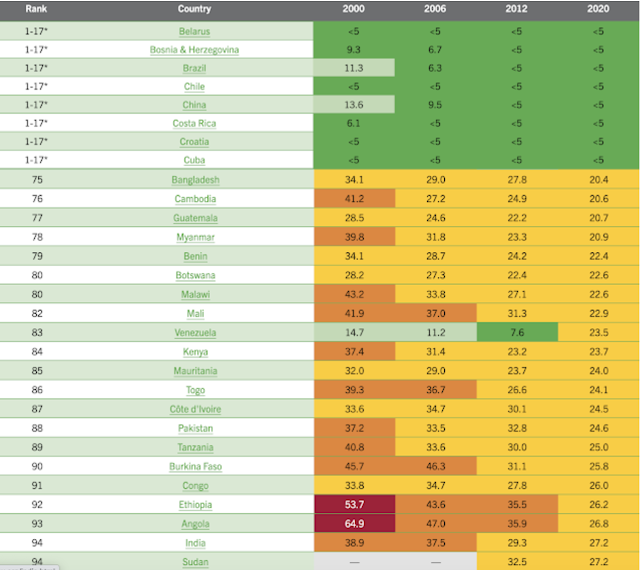

Youth unemployment for ages15-24 in India is 24.9%, the highest in South Asia region. It is 14.8% in Bangladesh 14.8% and 9.2% in Pakistan, according to the International Labor Organization and the World Bank.

|

| Youth Unemployment in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Source: ILO, WB |

In spite of the headline GDP growth figures highlighted by the Indian and world media, the fact is that it has been jobless growth. The labor participation rate (LPR) in India has been falling for more than a decade. The LPR in India has been below Pakistan's for several years, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

|

| Indian GDP Sectoral Contribution Trend. Source: Ashoka Mody |

|

| Indian Employment Trends By Sector. Source: CMIE Via Business Standard |

|

| World Hunger Rankings 2020. Source: World Hunger Index Report |

Hunger and malnutrition are worsening in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia because of the coronavirus pandemic, especially in low-income communities or those already stricken by continued conflict.

India has performed particularly poorly because of one of the world's strictest lockdowns imposed by Prime Minister Modi to contain the spread of the virus.

Hanke Annual Misery Index:

Pakistan's Real GDP:

Vehicles and home appliance ownership data analyzed by Dr. Jawaid Abdul Ghani of Karachi School of Business Leadership suggests that the officially reported GDP significantly understates Pakistan's actual GDP. Indeed, many economists believe that Pakistan’s economy is at least double the size that is officially reported in the government's Economic Surveys. The GDP has not been rebased in more than a decade. It was last rebased in 2005-6 while India’s was rebased in 2011 and Bangladesh’s in 2013. Just rebasing the Pakistani economy will result in at least 50% increase in official GDP. A research paper by economists Ali Kemal and Ahmad Waqar Qasim of PIDE (Pakistan Institute of Development Economics) estimated in 2012 that the Pakistani economy’s size then was around $400 billion. All they did was look at the consumption data to reach their conclusion. They used the data reported in regular PSLM (Pakistan Social and Living Standard Measurements) surveys on actual living standards. They found that a huge chunk of the country's economy is undocumented.

Pakistan's service sector which contributes more than 50% of the country's GDP is mostly cash-based and least documented. There is a lot of currency in circulation. According to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the currency in circulation has increased to Rs. 7.4 trillion by the end of the financial year 2020-21, up from Rs 6.7 trillion in the last financial year, a double-digit growth of 10.4% year-on-year. Currency in circulation (CIC), as percent of M2 money supply and currency-to-deposit ratio, has been increasing over the last few years. The CIC/M2 ratio is now close to 30%. The average CIC/M2 ratio in FY18-21 was measured at 28%, up from 22% in FY10-15. This 1.2 trillion rupee increase could have generated undocumented GDP of Rs 3.1 trillion at the historic velocity of 2.6, according to a report in The Business Recorder. In comparison to Bangladesh (CIC/M2 at 13%), Pakistan’s cash economy is double the size. Even a casual observer can see that the living standards in Pakistan are higher than those in Bangladesh and India.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Counterparts

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade Deficits

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Riaz Haq

World Inequality Report: Over 85% Of Indian Billionaires From Upper Castes, None From Scheduled Tribes

https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/world-inequality-report-over-85-of-...

India's income and wealth inequality, which declined post-independence, began to rise in the 1980s and has soared since the 2000s. Between 2014-15 and 2022-23, the increase in top-end inequality has been particularly striking in terms of wealth concentration. The top 1 per cent of income and wealth shares are now at their highest historical levels. Specifically, the top 1 per cent control over 40 per cent of total wealth in India, up from 12.5 per cent in 1980, and they earn 22.6 per cent of total pre-tax income, up from 7.3 per cent in 1980

This dramatic rise in inequality has made the "Billionaire Raj," dominated by India's modern bourgeoisie, more unequal than the British Raj. It places India among the most unequal countries globally. Current estimates indicate that it takes just ₹ 2.9 lakhs per year to be in the top 10 per cent of income earners and₹ 20.7 lakhs to join the top 1 per cent . In stark contrast, the median adult earns only about ₹ 1 lakh, while the poorest have virtually no income. The bottom 50 per cent of the population earns only 15 per cent of the total national income.

To fully grasp the skewed income distribution, one would have to be close to the 90th percentile to earn the average income. In terms of wealth, an adult needs ₹ 21 lakhs to be in the wealthiest 10 per cent and ₹ 82 lakhs to enter the top 1 per cent . The median adult holds approximately ₹ 4.3 lakhs in wealth, with a significant portion owning almost no wealth. The bottom 50 per cent holds only 6.4 per cent of the total wealth, while the top 1 per cent owns 40.1 per cent , and the top 0.001 per cent alone controls 17 per cent . This means fewer than 10,000 individuals in the top 0.001 per cent hold nearly three times the total wealth of the entire bottom 50 per cent (46 crore individuals).

Jun 29

Riaz Haq

1.6 Crore Jobs Lost Due To Note Ban, GST, Covid: India Ratings & Research Study

https://trak.in/stories/1-6-crore-jobs-lost-due-to-note-ban-gst-cov...

India’s informal sector has faced a series of macroeconomic shocks since 2016, leading to substantial economic losses. According to India Ratings and Research, the cumulative impact of these shocks, including demonetisation, the rollout of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), and the COVID-19 pandemic, has resulted in an estimated economic loss of ₹11.3 lakh crore or 4.3% of India’s GDP in 2022-23. This blog explores the severe impact on the informal sector, job losses, and the implications for India’s economy.

Impact of Macroeconomic Shocks

Demonetisation, GST, and COVID-19

The informal sector has been severely impacted by demonetisation, the GST rollout, and the COVID-19 pandemic. These shocks have disrupted the functioning of informal enterprises, leading to a decline in economic activity and job losses. Sunil Kumar Sinha, principal economist at India Ratings, noted that 63 lakh informal enterprises shut down between 2015-16 and 2022-23, resulting in the loss of about 1.6 crore jobs.

Decline in Economic Contribution

The Gross-Value Added (GVA) by unincorporated enterprises in the economy in 2022-23 was still 1.6% below the 2015-16 levels. Their compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) fell from 7.4% between 2010-11 and 2015-16 to a 0.2% contraction since then. The real GVA of unincorporated firms in manufacturing, trade, and other services (MTO) dropped significantly, with their share in India’s real MTO GVA falling from 25.7% in 2015-16 to 18.2% in 2022-23.

Employment Challenges

Job Losses and Sector Shrinkage

The informal sector has seen a significant decline in employment. The number of workers employed in the non-agricultural sector increased to 10.96 crore in 2022-23 from 9.79 crore in 2021-22. However, this was lower than the 11.13 crore people employed in the sector in the ‘pre-shock period’ of 2015-16. The manufacturing sector witnessed a notable decline in jobs, with employment dropping from 3.6 crore in 2015-16 to 3.06 crore in 2022-23.

Structural Shift Needed

India’s over 400 million informal labour market requires a structural shift to address the challenges posed by these macroeconomic shocks. The rise in the formalisation of the economy has led to robust tax collections, but the reduced unorganised sector footprint has implications for employment generation. The informal sector’s share in various sectors has decreased sharply, highlighting the need for measures to support and revitalise this critical part of the economy.

Future Prospects and Recommendations

Addressing the Decline

To mitigate the impact of these shocks and support the informal sector, India needs targeted policies and interventions. The government should focus on providing financial assistance, improving access to credit, and enhancing the business environment for informal enterprises. Additionally, measures to ensure job security and create new employment opportunities are crucial to addressing the challenges faced by the informal labour market.

Enhancing Economic Resilience

Strengthening the resilience of the informal sector is essential for sustained economic growth. Promoting digital literacy, enhancing skill development programs, and providing incentives for formalisation can help informal enterprises adapt to changing economic conditions. Ensuring social security and welfare measures for informal workers will also contribute to building a more inclusive and resilient economy.

Conclusion

India’s informal sector has borne the brunt of multiple macroeconomic shocks, resulting in significant economic losses and job reductions. Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive approach that supports informal enterprises, enhances economic resilience, and promotes inclusive growth. By implementing targeted policies and interventions, India can mitigate the impact of these shocks and ensure the sustained growth of its informal sector.

Jul 12

Riaz Haq

India ‘clearly has a problem’ finding new drivers for economic growth, JPMorgan’s Jahangir Aziz says

https://www.cnbc.com/2024/07/24/india-clearly-has-a-problem-finding...

India “clearly has a problem” figuring out new drivers for its economic growth even as its economy expands at a fast clip, JPMorgan’s Jahangir Aziz said, following the country’s union budget.

India’s chief economic advisor V Anantha Nageswaran said Monday that the economy is expected to grow at 6.5% to 7% in financial year 2025, lower than the Reserve Bank of India’s 7.2% growth forecast.

India “clearly has a problem” figuring out new drivers for its economic growth even as its economy expands at a fast pace, JPMorgan’s Jahangir Aziz said, following the country’s union budget.

“If you look at India over the last two years post the pandemic, recorded growth has been strong. But if you look at the drivers of growth, it’s essentially these two: Public infrastructure and services export,” Aziz, chief emerging markets economist at JPM, told CNBC’s “Street Signs Asia” on Tuesday.

The country’s finance minister on Tuesday said capital expenditure for fiscal year 2025 will be 11.11 trillion Indian rupees ($133.9 billion) — or 3.4% of GDP — backing India’s ambitions to enhance its physical and digital infrastructure as it strives to become a developed nation by 2047.

According to estimates by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, India’s services exports will likely hit $30.3 billion in June, compared with $27.8 billion in the same month last year.

“Services export is sort of stabilizing at a high level, it isn’t growing as fast as it was a couple years back,” Aziz said, adding that the government should focus on increasing private investments and boosting consumption.

“It is going to be very difficult for India to keep sustaining the 6% to 7% growth rate just on public infrastructure and on services export … The question is, can India broaden its growth drivers to consumption, but more importantly private investment? We haven’t seen that happen in a long, long time.”

India’s chief economic advisor V Anantha Nageswaran said Monday that the economy is expected to grow at 6.5% to 7% in financial year 2025, lower than the Reserve Bank of India’s 7.2% growth forecast.

According to the International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook, the country’s growth is predicted to decline to 6.5% in 2025.

Although India’s large youth population is steering the country toward becoming the world’s third largest consumer market by 2027, consumption is unlikely to increase if high unemployment stands in the way, warned Raghuram Rajan, professor at the University of Chicago Booth School and former governor of the Reserve Bank of India.

The country’s unemployment rate climbed to 9.2% in June, from 7% the month before, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

“You’ve seen consumption growth relatively tepid over the last few quarters, and unless people feel more confident that they have jobs, that they are well paying jobs, you are going to see that be a drag on growth,” Rajan said.

He questioned the employment initiatives such as pledging to train 2 million young people over five years, and providing a month’s worth of wages of about 15,000 rupees ($179) to first-time employees entering the workforce, announced in Tuesday’s budget.

“Are they of the magnitude that India requires given the enormous concerns about joblessness?”

Jul 25