PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

If you read Pakistan media headlines and donation-seeking NGOs and activists' reports these days, you'd conclude that the social sector situation is entirely hopeless. However, if you look at children's education and health trend lines based on data from credible international sources, you would feel a sense of optimism. This exercise gives new meaning to what former US President Bill Clinton has said: Follow the trend lines, not the headlines. Unlike the alarming headlines, the trend lines in Pakistan show rising school enrollment rates and declining infant mortality rates.

Key Social Indicators:

The quickest way to assess Pakistan's social sector progress is to look at two key indicators: School enrollment rates and infant mortality. These basic social indicators capture the state of schooling, nutrition and health care. Pakistan is continuing to make slow but steady progress on both of these indicators. Anything that can be done to accelerate the pace will help Pakistan move up to higher levels as proposed by Dr. Hans Rosling and adopted by the United Nations.

|

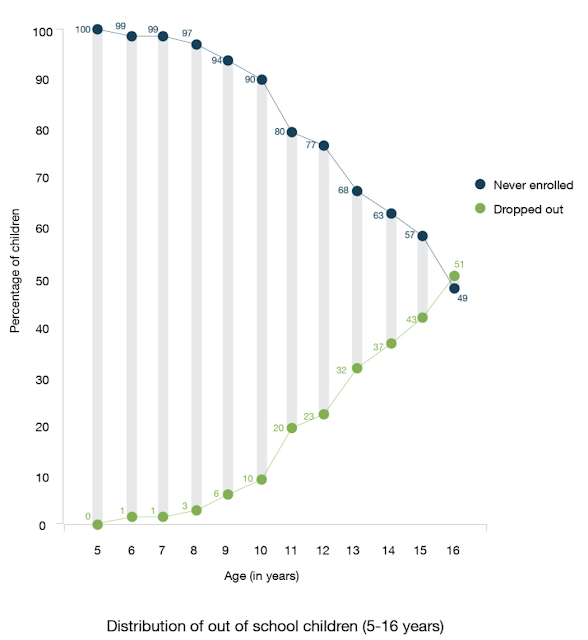

| Pakistan Children 5-16 In-Out of School. Source: Pak Alliance For Math & Science |

Rising Primary Enrollment:

Gross enrollment in Pakistani primary schools exceeded 97% in 2016, up from 92% ten years ago. Gross enrollment rate (GER) is different from net enrollment rate (NER). The former refers to primary enrollment of all students of all ages while the latter counts enrolled students as percentage of students in the official primary age bracket. The primary NER in Pakistan is significantly lower but the higher GER indicates many of these kids eventually enroll in primary schools albeit at older ages.

|

| Source: World Bank Education Statistics |

Declining Infant Mortality Rate:

The infant mortality rate (IMR), defined as the number of deaths in children under 1 year of age per 1000 live births in the same year, is universally regarded as a highly sensitive (proxy) measure of population health. A declining rate is an indication of improving health. IMR in Pakistan has declined from 86 in 1990-91 to 74 in 2012-13 and 62 in the latest survey in 2017-18.

During the 5 years immediately preceding the survey, the infant mortality rate (IMR) was 62 deaths per 1,000 live births. The child mortality rate was 13 deaths per 1,000 children surviving to age 12 months, while the overall under-5 mortality rate was 74 deaths per 1,000 live births. Eighty-four percent of all deaths among children under age 5 in Pakistan take place before a child’s first birthday, with 57% occurring during the first month of life (42 deaths per 1,000 live births).

Human Development Ranking:

It appears that improvements in education and health care indicators in Pakistan are slower than other countries in South Asia region. Pakistan's human development ranking plunged to 150 in 2018, down from 149 in 2017.

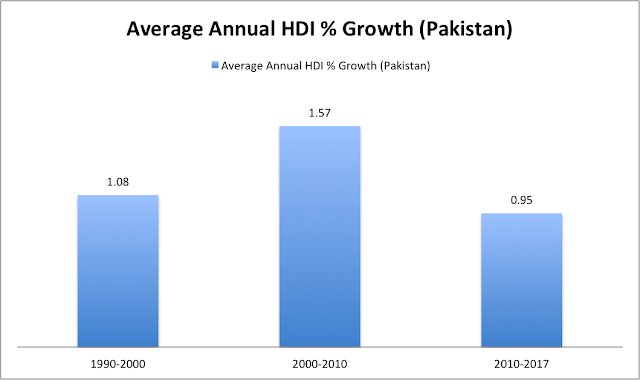

There was a noticeable acceleration of human development in #Pakistan during Musharraf years. Pakistan HDI rose faster in 2000-2008 than in periods before and after. Pakistanis' income, education and life expectancy also rose faster than Bangladeshis' and Indians' in 2000-2008.

Now Pakistan is worse than Bangladesh at 136, India at 130 and Nepal at 149. The decade of democracy under Pakistan People's Party and Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) has produced the slowest annual human development growth rate in the last 30 years. The fastest growth in Pakistan human development was seen in 2000-2010, a decade dominated by President Musharraf's rule, according to the latest Human Development Report 2018.

UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI) represents human progress in one indicator that combines information on people’s health, education and income.

Pakistan saw average annual HDI (Human Development Index) growth rate of 1.08% in 1990-2000, 1.57% in 2000-2010 and 0.95% in 2010-2017, according to Human Development Indices and Indicators 2018 Statistical Update. The fastest growth in Pakistan human development was seen in 2000-2010, a decade dominated by President Musharraf's rule, according to the latest Human Development Report 2018.

Pakistan@100: Shaping the Future:

Pakistani leaders should heed the recommendations of a recent report by the World Bank titled "Pakistan@100: Shaping the Future" regarding investments in the people. Here's a key excerpt of the World Bank report:

"Pakistan’s greatest asset is its people – a young population of 208 million. This large population can transform into a demographic dividend that drives economic growth. To achieve that, Pakistan must act fast and strategically to: i) manage population growth and improve maternal health, ii) improve early childhood development, focusing on nutrition and health, and iii) boost spending on education and skills for all, according to the report".

|

| Pakistan Child Mortality Rates. Source: PDHS 2017-18 |

During the 5 years immediately preceding the survey, the infant mortality rate (IMR) was 62 deaths per 1,000 live births. The child mortality rate was 13 deaths per 1,000 children surviving to age 12 months, while the overall under-5 mortality rate was 74 deaths per 1,000 live births. Eighty-four percent of all deaths among children under age 5 in Pakistan take place before a child’s first birthday, with 57% occurring during the first month of life (42 deaths per 1,000 live births).

|

| Pakistan Human Development Trajectory 1990-2018.Source: Pakistan HDR 2019 |

Human Development Ranking:

It appears that improvements in education and health care indicators in Pakistan are slower than other countries in South Asia region. Pakistan's human development ranking plunged to 150 in 2018, down from 149 in 2017.

| Expected Years of Schooling in Pakistan by Province |

There was a noticeable acceleration of human development in #Pakistan during Musharraf years. Pakistan HDI rose faster in 2000-2008 than in periods before and after. Pakistanis' income, education and life expectancy also rose faster than Bangladeshis' and Indians' in 2000-2008.

Now Pakistan is worse than Bangladesh at 136, India at 130 and Nepal at 149. The decade of democracy under Pakistan People's Party and Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) has produced the slowest annual human development growth rate in the last 30 years. The fastest growth in Pakistan human development was seen in 2000-2010, a decade dominated by President Musharraf's rule, according to the latest Human Development Report 2018.

UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI) represents human progress in one indicator that combines information on people’s health, education and income.

|

| Pakistan's Human Development Growth Rate By Decades. Source: HDR 2018 |

Pakistan saw average annual HDI (Human Development Index) growth rate of 1.08% in 1990-2000, 1.57% in 2000-2010 and 0.95% in 2010-2017, according to Human Development Indices and Indicators 2018 Statistical Update. The fastest growth in Pakistan human development was seen in 2000-2010, a decade dominated by President Musharraf's rule, according to the latest Human Development Report 2018.

|

| Pakistan Human Development Growth 1990-2018. Source: Pakistan HDR 2019 |

Pakistan@100: Shaping the Future:

Pakistani leaders should heed the recommendations of a recent report by the World Bank titled "Pakistan@100: Shaping the Future" regarding investments in the people. Here's a key excerpt of the World Bank report:

"Pakistan’s greatest asset is its people – a young population of 208 million. This large population can transform into a demographic dividend that drives economic growth. To achieve that, Pakistan must act fast and strategically to: i) manage population growth and improve maternal health, ii) improve early childhood development, focusing on nutrition and health, and iii) boost spending on education and skills for all, according to the report".

|

| Pakistani Children 5-16 Currently Enrolled. Source: Pak Alliance For Math & Science |

Summary:

The state of Pakistan's social sector is not as dire as the headlines suggest. There's reason for optimism. Key indicators show that education and health care in Pakistan are improving but such improvements are slower than in other countries in South Asia region. Pakistan's human development ranking plunged to 150 in 2018, down from 149 in 2017. It is worse than Bangladesh at 136, India at 130 and Nepal at 149. The decade of democracy under Pakistan People's Party and Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) has produced the slowest annual human development growth rate in the last 30 years. The fastest growth in Pakistan human development was seen in 2000-2010, a decade dominated by President Musharraf's rule, according to the latest Human Development Report 2018. One of the biggest challenges facing the PTI government led by Prime Minister Imran Khan is to significantly accelerate human development rates in Pakistan.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan's Expected Demographic Dividend

Can Imran Khan Lead Pakistan to the Next Level?

Democracy vs Dictatorship in Pakistan

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

Panama Leaks in Pakistan

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan's Expected Demographic Dividend

Can Imran Khan Lead Pakistan to the Next Level?

Democracy vs Dictatorship in Pakistan

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

Panama Leaks in Pakistan

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Riaz Haq

Pakistan Labor Force Survey (LFS) 2020-21

https://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/labour_force/publication...

Literacy rate goes up (62.4%, 62.8%) more in case of males (73.0%, 73.4%) than females

(51.5%, 51.9%). Area-wise rates suggest increase in rural (53.7%, 54.0%) and in urban

(76.1%, 77.3%). Male-female disparity seems to be narrowing down with the time span.

Literacy rate goes up in all provinces: KP (52.4%, 55.1%), Sindh (61.6%, 61.8%), Balochistan

(53.9%, 54.5%) and in Punjab (66.1%, 66.3%) during the comparative periods

-----------------

an average monthly wages of overall paid employees is of Rs.24028

per month while the median monthly wages is Rs. 18000 per month. . However, gender

disparities were obvious in the mean monthly wages gap between males and females of Rs.

4526 in favour of males. Based on median monthly wages, the gap, still in favour of males, is

Rs. 6,900. The above table also shows that irrespective of occupation both mean and median

monthly wages of males are higher than those of females

----------

4.20 Major Industry Divisions: Occupational Safety and Health

Mainly, the sufferers belong to agriculture (29.3%), construction (19.7%), manufacturing

(19.1%), wholesale & retail trade (13.7%) and transport/storage & communication (10.2%).

Female injuries in agriculture sectors are more than twice (61.7%) than that of male injuries

(26.3%). In manufacturing, female injuries (24.7%) and Community, social and personal services

(8.9%) are more than male injuries (18.6%) and (6.5%) respectively. Contrarily, males are

more vulnerable in the remaining groups. Comparative risk profiles run down for major

industries grouping while gain stream for manufacturing, transport, storage & communication

and community, social & personnel services.

May 30, 2022

Riaz Haq

World Bank approves $258m to support healthcare in Pakistan

https://www.dawn.com/news/1693770/world-bank-approves-258m-to-suppo...

The World Bank has approved $258 million to strengthen primary health care systems and accelerate national efforts towards universal health coverage in Pakistan, a press release issued by the international financial institution said on Wednesday.

The National Health Support Programme "complements ongoing investments in human capital and builds on health reforms that aim to improve quality and equitable access to healthcare services, especially in communities lagging behind national and regional-level health outcomes".

It identified three areas of focus for healthcare reforms under the initiative: healthcare coverage and quality of essential services, governance and accountability and healthcare financing.

Elaborating on these areas, the statement said the programme focused on healthcare coverage and quality of essential services to ensure availability of adequate staffing, supplies and medicines and to enhance patient referral systems for expediting emergency and higher-level care.

Similarly, the focus on governance and accountability was intended to strengthen oversight and management of primary healthcare services through real-time monitoring of available supplies and essential medicines.

The statement further explained that initiatives in this area included setting up a central information platform for provincial authorities to assess gaps in service delivery across public and private healthcare facilities.

Moreover, the focus on healthcare financing was to improve the financial management of primary healthcare centres for better expenditure tracking and budget forecasting to sustain quality healthcare services and delivery.

"The programme will benefit all communities through improvements to provincial primary healthcare systems, particularly [those] in approximately 20 districts that suffer from having the least access to health and nutrition services," the press release read.

According to the press release, the NHSP is co-financed by the International Development Association ($258 million) and two grants ($82 million) from the Global Financing Facility (GEF) for Women, Children and Adolescents (GFF), including a $40 million grant for protecting essential health services amid multiple global crises.

“The partnership between the GFF and the government of Pakistan focuses on building sustainable health systems while ensuring that all women, children and adolescents, especially in the most vulnerable communities can access the services they need amid multiple crises,” the statement quoted Monique Vledder, head of secretariat at GFF as saying.

"By investing in primary health care, strengthening the health workforce and equipping community health centres to both respond to emergencies and deliver quality services, Pakistan can drive a more equitable and resilient recovery,” she added.

World Bank Country Director for Pakistan, Najy Benhassine explained that “by strengthening provincial health systems, this programme is foundational to building the country’s human capital and improving health and nutrition outcomes for its citizens".

“Pakistan continues to make strides in health reforms toward ensuring access to primary healthcare services, especially for children and women during pregnancy and childbirth,” he said.

Hnin Hnin Pyne, task team leader for the programme, said: “NHSP creates a national forum for the federal and provincial governments to exchange lessons and collaborate on achieving sustainable health financing and high quality and coverage of essential services. It also helps strengthen engagement between public and private facilities and better coordination among development partners on future investments in health.”

Jun 8, 2022

Riaz Haq

KP Achieves Highest Literacy Rate Growth Among All Provinces

By Haroon Hayder

https://propakistani.pk/2022/06/09/kp-achieves-highest-literacy-rat...

The federal government has launched the Pakistan Economic Survey (PES) 2021-22, detailing how the national economy performed in the current fiscal year that will end on 30 June 2022.

Education Completion Rate

According to PES 2021-22, the Primary Education Completion Rate stood at 67%, Lower Education Completion Rate stood at 47%, and Upper Secondary Education Completion Rate stood at 23%. This shows that more students have completed their education till the primary level.

Literacy Parity Index stood at 0.71, Youth Literacy Parity Index stood at 0.82, Primary Parity Index stood at 0.88, and Secondary Parity Index stood at 0.89.

Pre-Primary Education

The participation rate in organized learning—one year before attaining the official age of entry to primary education— stood at 19%. This number, unfortunately, shows that little consideration is given to pre-primary education.

The percentage population in a given age group achieving at least a specific level of proficiency in functional, literacy, and numeracy skills stood at 60%.

Literacy Rate

In FY2020-21, the literacy rate stood at 62.8%; It was 62.4% in FY 2018-19.

Gender-wise

Gender-wise breakdown shows that the literacy rate among males increased to 73.4% in FY2020-21 from 73% in FY2018-19. The literacy rate among females increased slightly to 51.9% in FY2020-21 from 51.5% in FY 2018-19.

Area-wise

Area-wise analysis suggests that literacy rates in both rural and urban areas have increased. The literacy rate in rural areas increased from 53.7% in FY2018-19 to 54% in FY2020-21. The literacy rate in urban areas increased from 76.1% in FY 2018-19 to 77.3% in FY 2020-21.

Province-wise

Province-wise analysis shows literacy rates in all provinces have increased.

Punjab

The literacy rate in Punjab increased from 66.1% in FY2018-2019 to 66.3% in FY2020-21.

Sindh

The literacy rate in Sindh increased from 61.6% in FY2018-2019 to 61.8% in FY2020-21.

KP

The literacy rate in KP increased from 52.4% in FY2018-2019 to 55.1% in FY2020-21.

Balochistan

The literacy rate in Balochistan increased from 53.9% in FY2018-2019 to 54.5% in FY2020-21.

Initiatives to Improve Education Quality

During FY 2021-22, the federal and provincial governments launched various initiatives to raise the standards of education in line with Goal 4 of the UN SDGs.

These initiatives are:

Enhancing access to education by establishing new schools

Upgrading the existing schools

Improving the learning environment by providing basic educational facilities

Digitization of educational institutions

Enhancing the resilience of educational institutions to cater to unforeseen situations

Promoting distance learning, capacity building of teachers

Improving the hiring of teachers, particularly hiring of science teachers to address the issues of science education

Single National Curriculum

The Single National Curriculum was launched as PTI’s flagship scheme envisioning minimizing the disparity in Pakistan’s education system and providing equal learning opportunities to all segments of society. There are three education systems in the country; public educational institutes, private educational institutes, and religious seminaries.

The SNC will be implemented in three phases. The first phase has been concluded as a uniform curriculum has been introduced from pre 1 to 5 classes at the beginning of the academic year 2021-22.

Jun 9, 2022

Riaz Haq

Pakistan Economic Survey: Health & Nutrition 2021-22

https://www.finance.gov.pk/survey/chapter_22/PES11-HEALTH.pdf

Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) in Pakistan has declined to 54.2 deaths per 1,000 live births

in 2020 from 55.7 in 2019, while Neonatal Mortality Rate declined to 40.4 deaths per

1,000 live births in 2020 from 41.2 in 2019. Percentage of birth attended by skilled

health personnel increased to 69.3 percent in 2020 from 68 percent in 2019 (DHS & UNICEF). Maternal Mortality Ratio fell to 186 maternal deaths per 100,000 births in

2020, from 189 in 2019 (Table 11.1).

With a population growing at 2 percent per annum, Pakistan’s contraceptive prevalence

rate in 2020 decreased to 33 percent from 34 percent in 2019 (Trading Economics).

Pakistan’s tuberculosis incidence is 259 per 100,000 population and HIV prevalence rate

is 0.12 per 1,000 population in 2020.

Table 11.1: Health Indicators of Pakistan

2019 2020

Maternal Mortality Ratio (Per 100,000 Births)* 189 186

Neonatal Mortality Rate (Per 1,000 Live Births) 41.2 40.4

Mortality Rate, Infant (Per 1,000 Live Births) 55.7 54.2

Under-5 Mortality Rate (Per 1,000) 67.3 65.2

Incidence of Tuberculosis (Per 100,000 People) 263 259

Incidence of HIV (Per 1,000 Uninfected Population) 0.12 0.12

Life Expectancy at Birth, (Years) 67.3 67.4

Births Attended By Skilled Health Staff (% of Total)** 68.0 (2015) 69.3 (2018)

Contraceptive Prevalence, Any Methods (% of Women Ages 15-49) 34.0 33

Source: WDI, UNICEF, Trading Economics & Our World in data

-----------

Food and nutrition

Calories/day 2019-20 2457 2020-21 2786 2021-22 2735

-------

Table 11.9: Availability of Major Food Items per annum (Kg per capita)

Food Items 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 (P)**

Cereals 139.9 170.8 164.7

Pulses 7.8 7.6 7.3

Sugar 23.3 28.5 28.3

Milk (Liter) 168.7 171.8 168.8

Meat (Beef, Mutton, Chicken) 22.0 22.9 22.5

Fish 2.9 2.9 2.9

Eggs (Dozen) 7.9 8.2 8.1

Edible Oil/ Ghee 14.8 15.1 14.5

Fruits & Vegetables 53.6 52.4 68.3

Calories/day 2457 2786 2735

Source: M/o PD&SI (Nutrition Section)

Jun 9, 2022

Riaz Haq

Pakistan Economic Survey: Education 2021-22

https://www.finance.gov.pk/survey/chapter_22/PES10-EDUCATION.pdf

Pakistan is committed to transform its education system into a high-quality global

market demand driven system in accordance with the Goal 4 of Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs) which pertains to quality of education. The progress

achieved by Pakistan so far on Goal 4 of SDGs is as under:

Primary, Lower and Upper Secondary Education Completion Rate stood at 67

percent, 47 percent and 23 percent, respectively, depicting higher Primary

attendance than Lower and Upper Secondary levels.

Parity Indices at Literacy, Youth Literacy, Primary and Secondary are 0.71, 0.82, 0.88

and 0.89, respectively.

Participation rate in organized learning (one year before the official primary entry

age), by sex is 19 percent showing a low level of consideration of Pre-Primary

Education.

Percentage of population in a given age group achieving at least affixed level of

proficiency in functional; (a) literacy and (b) numeracy skills is 60 percent.

--------

Literacy, Gross Enrolment Rate (GER) and Net Enrolment Rate (NER)

Literacy

During 2021-22, PSLM Survey was not conducted due to upcoming Population and

Housing Census 2022. Therefore, the figures for the latest available survey regarding

GER and NER may be considered for the analysis. However, according to Labour Force

Survey 2020-21, literacy rate trends shows 62.8 percent in 2020-21 (as compared to

62.4 percent in 2018-19), more in males (from 73.0 percent to 73.4 percent) than

females (from 51.5 percent to 51.9 percent). Area-wise analysis suggest literacy increase

in both rural (53.7 percent to 54.0 percent) and urban (76.1 percent to 77.3 percent).

Male-female disparity seems to be narrowing down with time span. Literacy rate gone

up in all provinces, Punjab (66.1 percent to 66.3 percent), Sindh (61.6 percent to 61.8

percent), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (52.4 percent to 55.1 percent) and Balochistan (53.9

percent to 54.5 percent). [Table10.2].

Table 10.2: Literacy Rate (10 Years and Above) (Percent)

Province/Area 2018-19 2020-21

Male Female Total Male Female Total

Pakistan 73.0 51.5 62.4 73.4 51.9 62.8

Rural 67.1 40.4 53.7 67.2 40.8 54.0

Urban 82.2 69.7 76.1 83.5 70.8 77.3

--------

During 2021-22, PSLM Survey was not conducted due to upcoming Population and

Housing Census 2022. Therefore, the figures for the latest available survey are reported

here.

Table 10.3: National and Provincial GER (Age 6 -10 years) at Primary Level (Classes1-5)(Percent)

Province/Area 2014-15 2019-20

Male Female Total Male Female Total

Pakistan 98 82 91 89 78 84

Punjab 103 92 98 93 90 92

Sindh 88 69 79 78 62 71

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

(Including Merged Areas)

- - - 96 73 85

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

(Excluding Merged Areas)

103 80 92 98 79 89

Balochistan 89 54 73 84 56 72

Source: Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) District Level Survey, 2019-20,

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

-------------

Annual Status of Education Report (ASER)

Annual Status of Education Report (ASER-Rural) 2021, is the largest citizen-led

household-based learning survey across all provinces/areas: Sindh, Balochistan, Punjab,

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Gilgit Baltistan (GB), Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) and

Azad Jammu Kashmir (AJK). According to the ASER 2021, 10,000 trained

volunteer/enumerators surveyed 87,415 households in 4,420 villages across 152 rural

districts of Pakistan. Detailed information of 247,978 children aged 3-16 has been

collected (57 percent male and 43 percent female), and of these, 212,105 children aged

5-16 years were assessed for language and arithmetic competencies. Moreover, 585

transgenders were also a part of the surveyed sample. Major findings of ASER 2021 and

its comparison with 2019 is given in Box-II

Jun 9, 2022

Riaz Haq

http://live.clintonglobalinitiative.org #CGI2016

Jun 10, 2022

Riaz Haq

While the majority of people surveyed consume news regularly, 38% said they often or sometimes avoid the news – up from 29% in 2017 – the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism said in its annual Digital News Report. Around 36% – particularly those under 35 – say that the news lowers their mood.

https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/more-people-are-avoi...

-------------------

Positive News | Good journalism about good things - Positive News

Positive News is the magazine for good journalism about good things.

When much of the media is full of doom and gloom, instead Positive News is the first media organisation in the world that is dedicated to quality, independent reporting about what’s going right.

We are pioneers of ‘constructive journalism’ – a new approach in the media, which is about rigorous and relevant journalism that is focused on progress, possibility, and solutions. We publish daily online and Positive News magazine is published quarterly in print.

As a magazine and a movement, we are changing the news for good.

Jun 15, 2022

Riaz Haq

Good news about what is going right in the world is hard sell today.

But look at the trend lines; more than a billion people have been lifted out of extreme poverty since 1990. We have dramatically reduced people dying of tuberculosis and malaria on all continents. Infant mortality is going down.

https://youtu.be/SQZ6JmpFrfs

Jun 15, 2022

Riaz Haq

Indonesia to provide 2.5m metric tons of #palm #oil to #Pakistan on urgent basis. First ship carrying 30,000 metric tons of oil from Indonesia left for Pakistan on Tuesday. #edibleoil #cookingoil #palmoil

ISLAMABAD (Dunya News) - Ten ships of edible oil will arrive in Pakistan in the next two weeks from Indonesia and Malaysia.

After successful negotiations of Pakistani delegation that visited Indonesia, it was agreed between the two countries that Indonesia will provide 2.5 million metric tons of edible oil to Pakistan on urgent basis.

According to a statement released today by Prime Minister’s Office, the delegation visited Indonesia on the directions of Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif. Earlier, the Prime Minister talked to the Indonesian President Joko Widodo in this regard.

The first ship carrying 30,000 metric tons of edible oil from Indonesia will leave for Pakistan on Tuesday.

https://dunyanews.tv/en/Business/655987-Indonesia-provide-2-5m-metr...

Jun 15, 2022

Riaz Haq

Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR)

Country Name Per 100K Live Births

India 145.00

Timor-Leste 142.00

Pakistan 140.00

-------------------

Pakistan Maternal Mortality Rate 2000-2022

https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/PAK/pakistan/maternal-mortali...

Maternal mortality ratio is the number of women who die from pregnancy-related causes while pregnant or within 42 days of pregnancy termination per 100,000 live births. The data are estimated with a regression model using information on the proportion of maternal deaths among non-AIDS deaths in women ages 15-49, fertility, birth attendants, and GDP.

Pakistan maternal mortality rate for 2017 was 140.00, a 2.1% decline from 2016.

Pakistan maternal mortality rate for 2016 was 143.00, a 7.14% decline from 2015.

Pakistan maternal mortality rate for 2015 was 154.00, a 4.35% decline from 2014.

Pakistan maternal mortality rate for 2014 was 161.00, a 3.01% decline from 2013.

Jul 2, 2022

Riaz Haq

The average expected years of schooling in Pakistan is 8.5 years. In comparison it is 11.2 years in Bangladesh and 12.3 years in India. Pakistan has performed poorly even on inequality adjusted human development, as well as gender development and equality compared with the regional countries.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1522407#:~:text=The%20average%20expected%....

Jul 5, 2022

Riaz Haq

What is the status of food security in Pakistan?

Pakistan is presently self-sufficient in major staples – ranked at 8th in producing wheat, 10th in rice, 5th in sugarcane, and 4th in milk production. Despite that, only 63.1 percent of the country's households are “food secure”, according to the Ministry of Health and Unicef's National Nutritional Survey 2018.

---------

More worryingly, almost half of the children under 5 years are stunted (low-height-for-age) and one in ten has been suffering from wasting (low-weight-forheight) in the country. Incorporating these factors, Pakistan was ranked 106th

among 119 countries surveyed for the Global Hunger Index, and has been

characterized as facing a “serious” level of hunger (Figure S2.2). In fact, Pakistan

is among those seven countries that cumulatively account for two-thirds of the world’s under-nourished population (along with Bangladesh, China, Congo,

Ethiopia, India and Indonesia)

https://www.sbp.org.pk/reports/quarterly/fy19/Third/Special-Section...

Jul 7, 2022

Riaz Haq

Senator Dr Sania Nishtar

@SaniaNishtar

Pakistan's first ever end-to-end digital targeted subsidies program #Ehsaas Rashan Riayat (implementation of which was underway) has been closed down, which means 20 million eligible families will not have access to 30% monthly subsidy on 3 grocery items. https://bit.ly/3zawG1M

https://twitter.com/SaniaNishtar/status/1548000577803563008?s=20&am...

Each year, Pakistan spends billions of rupees in untargeted federal and provincial subsidies across sectors. Much of these government transfers are subject to elite capture, subsidizing producers, corporations, and middlemen instead of reaching the poorest households.

Earlier this year, Ehsaas sought to address this issue by launching the first-of-its-kind, end-to-end-digitized targeted commodity subsidy programme, called Ehsaas Rashan Riayat. The programme established infrastructure to deliver government subsidies directly to millions of deserving households.

------------------

Unfortunately, the current government has decided to end the programme as of July 1, 2022, and instead committed Rs16 billion in untargeted subsidy to be disbursed through Utility Stores. Utility Stores are meant to provide subsidized ‘rashan’ without any digital targeting or verification. This will open avenues for collusion and elite capture. Given fiscal constraints and double-digit inflation, which is placing a disproportionate burden on the poor, I would urge the federal government to reconsider its decision and use the Ehsaas Rashan Riayat mechanism, instead.

Ehsaas Rashan Riayat was launched after extensive stakeholder consultations and has several features, which can be a gamechanger to target support to poor households while minimizing likelihood of corruption or elite capture. To make sure that public money is targeted, the programme created objective criteria for beneficiary eligibility, based on socioeconomic conditions drawing on data infrastructure of the 2021 National Socioeconomic Registry.

The backbone of the programme is the nationwide network of kiryana, Utility, and CSD stores, which were leveraged for disbursing the subsidy, instead of creating new distribution channels. Through an extensive process of engagement with merchant unions, visits to multiple cities, social mobilization, and grassroots awareness campaigns, the programme achieved a retail outlet footprint in 84 per cent of districts across Pakistan, to develop a network of 15,000+ merchants. This helped us reach the poorest families by mobilizing distribution channels wherever they lived. The plan was to reach more than 50,000 merchants by the end of the 2022 calendar year.

A key feature of the programme was to digitize the entire network of participating stores. These stores were linked in real-time through a mobile app of the National Bank of Pakistan, which was used to conduct subsidy transactions, with the subsidy given as a digital voucher. This programme enabled small, often informal kiryana stores to become more technologically savvy. Additionally, by connecting these merchants in an online database and geotagging them, the programme started digitally documenting a previously undocumented part of the economy.

The programme improved financial inclusion for thousands of unbanked small merchants by facilitating the opening of bank accounts. These merchants were reimbursed for the subsidy disbursed, in near real-time, through an entirely digital payment mechanism. These small merchants were to get access to banking services, including saving, transacting, and using other financial instruments, which could help further scale their businesses.

Jul 15, 2022

Riaz Haq

Senator Dr Sania Nishtar

@SaniaNishtar

Pakistan's first ever end-to-end digital targeted subsidies program #Ehsaas Rashan Riayat (implementation of which was underway) has been closed down, which means 20 million eligible families will not have access to 30% monthly subsidy on 3 grocery items. https://bit.ly/3zawG1M

https://twitter.com/SaniaNishtar/status/1548000577803563008?s=20&am...

Ehsaas Rashan Riayat was also meant to provide an ecosystem where cash recipients of Ehsaas benefits could potentially transition into digital payment practices, thus eliminating pilferage and interplay of extractive middlemen.

The underlying digital ecosystem that was set up as part of this programme was agile and had immense potential to be scaled even further. Initially, we used a demand-based model in which people had to SMS a request. The next model was based on pre-qualification of all the eligible beta families, developing pools of CNICs and corresponding registered SIMS for each eligible beta family, allowing any family member to visit their nearest merchant with their phone and CNIC to avail of the subsidy, without the need to register or wait weeks for verification. Just before I left office, I convened a steering committee meeting to approve detailed modalities of the new registration model.

If the programme is continued, its infrastructure could also be utilized to expand the range of subsidized commodities. Other household food essentials – beyond wheat, pulses, and cooking oil – could be added with minor backend changes in the program’s infrastructure. The monthly subsidy amount can be increased. The plan was to use the system beyond groceries, for subsidies on fuel and outpatient healthcare assistance, which is not covered by health insurance.

Our country faces economically challenging times, where drastic measures will be needed to address the far-reaching effects of the rising fiscal deficit. Ehsaas Rashan Riayat provides an opportunity for the government to take the lead in exercising fiscal prudence and to phase out untargeted subsidies, in favour of targeted support to households that need it most while at the same time address corruption.

The government must reconsider its decision and continue the operation and expansion of Ehsaas Rashan Riayat in the public interest.

Jul 15, 2022

Riaz Haq

India, Pakistan tackle backslide in child immunizations

https://www.news-medical.net/news/20220727/India-Pakistan-tackle-ba...

While India and Pakistan topped the list of countries that saw the greatest increase in children not receiving a first dose of DTP between 2019 and 2020, they were also quick to bounce back.

Pakistan now figures among countries that successfully fought back declines to return to pre-pandemic levels of coverage "thanks to high-level government commitment and significant catch-up immunization efforts", UNICEF/WHO said.

In India, progress towards reducing the number of zero-dose children was impacted by the pandemic and the number of children who did not receive the first dose of the DTP vaccine was estimated to have increased to three million in 2020, up from 1.4 million in 2019, according to Mainak Chatterjee, health specialist at UNICEF India.

"Despite having the largest birth cohort in the world, India was able to prevent a further backslide through special drives such as the Intensified Mission Indradhanush, which enabled the country to bring down zero-dose to 2.7 million in 2021," Chatterjee told SciDev.Net.

Jul 28, 2022

Riaz Haq

#Pakistan managed to bounce back to its overall #child #vaccination rates in spite of disruptions due to the #COVID #pandemic. #health #immunization https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/pakistan-can-how-one-country-repa...

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1558266057206288384?s=20&...

“Pakistan can”: How one country repaired its routine immunisation safety net

As the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020, Pakistan’s routine immunisation programme took a heavy hit. But while many countries continued to struggle to make up lost ground in 2021, Pakistan bounced back to pre-pandemic levels of protection. VaccinesWork spoke to country health leaders to find out what went right.

https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/pakistan-can-how-one-country-repa...

New data confirms what public health officials hoped was true: in 2021, Pakistan’s children were very nearly as well-protected against preventable diseases as they had been in 2019. That may not sound like a landmark triumph, but it is – and here’s why.

Like in most countries, routine immunisation in Pakistan suffered a gut-punch – if not quite a knockout blow – when the pandemic landed in early 2020. Mario Jimenez, who has worked on Gavi’s Pakistan programme since 2019, says, “The lockdowns started, and that led to the immediate stop of outreach activities, and a subsequent accumulation of children that were not being reached with routine immunisation.”

Even once the lockdowns lifted, recalls Dr Faisal Sultan, former Special Assistant to the Prime Minister on Health, fear of infection continued to inhibit contact between people and the health system. And even making it to the clinic didn’t always mean a child would get their jab: Pakistan struggled with periodic vaccine stock-outs as shipping and air travel stumbled to a halt globally.

“It really pushed the country and ourselves to reflect about how we can adapt to the situation, and what can be done to recover some of the losses that were taking place,” says Jimenez. These were urgent conversations: the real-world danger signalled by those losses was plain to everyone involved.

Pakistan has a massive birth cohort – more than 16,000 children are born each day. “In a matter of days,” Jimenez says, “we could have a very large number of unprotected unvaccinated children.” With the vaccine levee crumbling, every small disease outbreak risked becoming an epidemic flash-flood.

From July 2020, the health system kicked into high gear, beefing up outreach, and finding novel means to trace unvaccinated “zero-dose” children. Life-saving gains were made.

Aug 12, 2022

Riaz Haq

The headline multidimensional poverty (MPI) figures for Pakistan (0.198) are worse than for Bangladesh (0.104) and India (0.069). This is primarily due to the education deficit in Pakistan. UNDP's report titled "Unpacking Deprivation Bundle" shows that an average Pakistani still enjoys a better "standard of living" than his/her counterparts in Bangladesh and India. Below is an excerpt from it:

"The analysis first looks at the most common deprivation profiles across 111 developing countries (figure 1). The most common profile, affecting 3.9 percent of poor people, includes deprivations in exactly four indicators: nutrition, cooking fuel, sanitation and housing.7 More than 45.5 million poor people are deprived in only these four indicators.8 Of those people, 34.4 million live in India, 2.1 million in Bangladesh and 1.9 million in Pakistan—making this a predominantly South Asian profile "

https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/hdp-document/2022mpirep...

Also note in this UNDP report that the income poverty (people living on $1.90 or less per day) in Pakistan is 3.6% while it is 22.5% in India and 14.3% in Bangladesh.

Living standards (Cooking fuel Sanitation Drinking water Electricity Housing Assets) of the poor in Pakistan (31.1%) are better than in Bangladesh (45.1%) and India (38.5%).

Pakistan fares worse in terms of education (41.3%) indicators relative to Bangladesh (37.6%) and India (28.2%).

In terms of health, Pakistan ( 27.6%) fares better than India (32.2%) but worse than Bangladesh (17.3%).

In terms of population vulnerable to poverty, Pakistan (12.9%) does better than Bangladesh (18.2%) and India (18.7%)

Oct 17, 2022

Riaz Haq

Ahmed Jamal Pirzada

@ajpirzada

Doesn't look good for Pak: the human capital index has stayed flat since 2005. While "avg years of schooling" has increased from 4 years in 2000 to 6 years in 2015 (Barro-Lee dataset), the quality has not improved. Worse, the gap with regional countries has increased since 80s.

https://twitter.com/ajpirzada/status/1583239244168200193?s=20&t...

Oct 20, 2022

Riaz Haq

The HDI is a summary measure for assessing long-term progress in three basic dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living. Pakistan's HDI value for 2021 is 0.544— which put the country in the Low human development category—positioning it at 161 out of 191 countries and territories.

Between 1990 and 2021, Pakistan's HDI value changed from 0.400 to 0.544, an change of 36.0 percent.

Between 1990 and 2021, Pakistan's life expectancy at birth changed by 6.0 years, mean years of schooling changed by 2.2 years and expected years of schooling changed by 4.0 years. Pakistan's GNI per capita changed by about 62.7 percent between 1990 and 2021.

https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/specific-country-data#/countries/PAK

-------

Pakistan has dropped seven places in the Human Development Index, ranking 161 out of 192 countries in the 2021-2022 HDI, according to the UNDP report released on Thursday.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/989724-pakistan-down-on-human-deve...

In the previous year, Pakistan had stood at 154 out of 189 countries.

As per the report, Pakistan’s life expectancy at birth is 66.1 years and expected years of schooling are 8. The country’s gross per capita national income is $4,624. The report has identified that different climate shocks are affecting world order, pushing back the growth that was achieved in the past few years. While doing so, it has categorised the floods in Pakistan as “an example of the climate shocks seen around the world.”

Switzerland leads the way on the latest HDI while Norway and Iceland enjoy second and third positions. Among the nine South Asian countries -- Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Islamic Republic of Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka -- only Pakistan and Afghanistan (180th position) are in the low human development category.

Bhutan (127), Bangladesh (129), India (132) and Nepal (143) are in the medium human development category. And crisis-riddled Sri Lanka has managed to improve its position by 9 points, reaching the 73rd position on the index, finding itself in the high human development category. Iran is three positions behind at 76; the next is Maldives at the 90th position.

The report, titled ‘Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World’ has found out that around 90 per cent of countries have seen “reversals in human development” in the year of the survey, pointing to a world stuck in a never-ending cycle of crisis after crisis, causing global disruptions. Per the report, the two major factors responsible for these disruptions were the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war.

The Human Development Index is a measure of countries’ standard of living, health and education. This is the first time in the last 30 years that human development in a majority of countries has gone in reverse for two consecutive years.

This has pushed human development to its 2016 levels, a huge blow to the progress made on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that were meant to be completed by 2030. For the year 2021, the UN had projected an HDI value of 0.75 -- the actual value has come out to be 0.732.

The report adds that the world is in a “new uncertainty complex”. Such uncertainty is created by the two years of Covid-19 which saw a series of the lethal waves of the virus.

Even though the world took quick steps to defeat the virus, the report notes, and developed vaccines to counter the threats, unequal distribution of the vaccines has created more problems in a number of low-income countries.

The pandemic-induced lockdowns and school closures also took a toll on people’s mental wellbeing across the world. The report has found out that mental distress among male minority groups in the UK saw the largest increase, and men from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan were the most affected by the disruptions caused by the pandemic.

Oct 22, 2022

Riaz Haq

INTERGENERATIONAL ECONOMIC MOBILITY: THE CASE OF NORTH-

WESTERN PAKISTAN

Ansa Javed Khan1, Sajjad Ahmad Jan2, Jawad Rahim Afridi3*, Arshia Hashmi4, Muhammad Azeem Ahmed5 1Assistant Director, P&D, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, Pakistan; 2Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan; 3*Lecturer, Department of Economics, Sarhad University of Science & IT, Peshawar, Pakistan; 4Assistant Professor, The University of Faisalabad, Department of Management Studies, Faisalabad, Pakistan; 5Associate Professor, Barani Institute of Sciences, Pakistan.

Email: 1*director_pnd@bkuc.edu.pk, 2sajjadahmadjan@uop.edu.pk, 3*jrafridi67@gmail.com, 4arshia.hashim@tuf.edu.pk, 5azeem@baraniinstitute.edu.pk

Article History: Received on 19th June 2021, Revised on 26th June 2021, Published on 29th June 2021

https://www.sciencegate.app/document/10.18510/hssr.2021.93141

Access to Education and Intergenerational Economic Mobility

The following table 1 shows the change in educational status which has taken place between the parents and children’s generations for the overall sample as well as for the sub-groups (Majority and Minority Tribes). The absolute numbers (outside parentheses) and the percentage (within parentheses) in different cells of the table show the people who are illiterate or at different levels of education. The table on one hand shows the intergenerational mobility of people up and down the education ladder and on the other hand reveals the wide and persistent educational gap between the majority and minority tribes. The table shows that 26 % of the respondents in the kids’ generation do not have any education versus 46 % in the parents’ generation. The results affirm the government’s claims and the common perception that, on average, more people have become literate through time and therefore the people in the children’s generation are more likely to be educated than their parent's generation. Further, the college and university graduates in the children’s generation outnumber the school graduates while school graduates outnumber the higher two educational categories in the parents’ generation as most of the students in past used to drop out at both primary or high school levels and couldn’t manage to get into a college or university for higher studies.

The aggregate results for the whole sample are actually driven by the majority tribes as it shows identical trends from the parents’ generation to the children’s generation in all educational. The majority tribe has succeeded in decreasing the number of illiterates from 33% in the parents’ generation to 11% in the children’s generation. College and university graduates (total of 60%) outnumber the school graduates and the illiterate (total of 40%) in the children’s generation as compared to the parents’ generation in the majority tribe where the former is 26% and the latter is 73%. This indicates a visible upward movement of the educational ladder by the members of the majority tribe. The situation of education and literacy in the minority tribe is deplorable if the comparison is either made on basis of children’s and parents’ generations or if the educational attainment levels of the minority and majority tribes are compared. The illiterates outnumber all the other educational categories as in sharp contrast to the educational attainment levels of the majority tribe. The data further reveals that no or only a negligible improvement in the educational status of the people belonging to the minority tribe has taken place between the children’s and parents’ generations. This affirms our presumption that in the North-Western parts of Pakistan, the tribal affiliation of a person determines his or her access to education. The ease of access to education then further transforms into economic mobility or immobility of the people.

Nov 13, 2022

Riaz Haq

Pakistan Demographic Survey 2020

https://www.dawn.com/news/1721179

The latest figures showed that although the overall life expectancy has dropped, it rose among men from 64.3 to 64.5. For women, it fell from 66.5 to 65.5 but was still higher than for men.

Life expectancy also increased for the 1-4 age group to 71.3, including 70.6 for males and 72 for females.

The infant mortality rate has fallen to 56 deaths per 1,000 live births. It was 60 in PSLM 2018-19, and 62 in PDHS 2017-18.

While the general fertility rate was 124, the age-specific data shows the rate was highest in the 25-29 age group at 215, followed by 176 in the 20-24 age group, 164 in the 30-34 age group, and 94 in the 35-39 age group.

This last age group (35-39) also saw the most significant jump when compared with the PDHS figure of 79.

The general fertility rate was also quite higher in rural areas (138) compared to urban areas (102).

The PDS shows that the country’s population has reached from 207.6m in 2017 to 220.42m now, including 111.69m men and 108.73m women. Most people continue to live in rural areas (139.41m) compared to urban areas (81m).

https://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/population/publications/...

Nov 16, 2022

Riaz Haq

Bilal I Gilani

@bilalgilani

Continuing with looking at the brighter side of our development

Burden of disease has declined from 70,086 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)32 lost per 100,000

people in 1990 to 42,059 in 2019 due to decreases in CDs and improvements in maternal and

child health;

https://twitter.com/bilalgilani/status/1610718511369797655?s=20&...

Jan 4, 2023

Riaz Haq

TFR Fertility Trend in Pakistan:

Past

Forecasted

1990 2017 2100

Pakistan

6.1 3.4 1.3

South Asia

6.1 3.4 1.3

Global

3.1 2.4 1.7

https://www.healthdata.org/pakistan

Jan 4, 2023

Riaz Haq

Lancet Study: Non-infectious diseases cause early death in Pakistan

BY MUNIR AHMED, ASSOCIATED PRESS - 01/19/23 4:04 AM ET

https://thehill.com/homenews/ap/ap-health/ap-study-non-infectious-d...

Pakistan has considerable control over infectious diseases but now struggles against cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer as causes of early deaths, according to a new study published Thursday.

The Lancet Global Health, a prestigious British-based medical journal, reported that five non-communicable diseases — ischaemic heart disease, stroke, congenital defects, cirrhosis, and chronic kidney disease — were among the 10 leading causes of early deaths in the impoverished Islamic nation.

However, the journal said some of Pakistan’s work has resulted in an increase in life expectancy from 61.1 years to 65.9 over the past three decades. The change is due, it said, “to the reduction in communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases.” That’s still 7.6 years lower than the global average life expectancy, which increased over 30 years by 8% in women and 7% in men.

The study says “despite periods of political and economic turbulence since 1990, Pakistan has made positive strides in improving overall health outcomes at the population level and continues to seek innovative solutions to challenging health and health policy problems.”

The study, which was based on Pakistan’s health data from 1990 to 2019, has warned that non-communicable diseases will be the leading causes of death in Pakistan by 2040.

It said Pakistan will also continue to face infectious diseases.

“Pakistan urgently needs a single national nutrition policy, especially as climate change and the increased severity of drought, flood, and pestilence threatens food security,” said Dr. Zainab Samad, Professor and Chair of the Department of Medicine at Aga Khan University, one of the authors of the report.

“What these findings tell us is that Pakistan’s baseline before being hit by extreme flooding was already at some of the lowest levels around the globe,” said Dr. Ali Mokdad, Professor of Health Metrics Sciences at IHME. “Pakistan is in critical need of a more equitable investment in its health system and policy interventions to save lives and improve people’s health.”

The study said with a population approaching 225 million, “Pakistan is prone to the calamitous effects of climate change and natural disasters, including the 2005 Kashmir earthquake and catastrophic floods in 2010 and 2022, all of which have impacted major health policies and reform.”

It said the country’s major health challenges were compounded by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and last summer’s devastating flooding that killed 1,739 people and affected 33 million.

Researchers ask Pakistan to “address the burden of infectious disease and curb rising rates of non-communicable diseases.” Such priorities, they wrote, will help Pakistan move toward universal health coverage.”

The journal, considered one of the most prestigious scientific publications in the world, reported on Pakistan’s fragile healthcare system with the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington’s School of Medicine. The study was a collaboration with a Karachi-based prestigious Aga Khan University and Pakistan’s health ministry.

The study also mentioned increasing pollution as one of the leading contributors to the overall disease burden in recent years. Pakistan’s cultural capital of Lahore was in the grip of smog on Thursday, causing respiratory diseases and infection in the eyes. Usually in winter, a thick cloud of smog envelops Lahore, which in 2021 earned it the title of the world’s most polluted city.

Jan 19, 2023

Riaz Haq

Library thrives in Pakistan’s ‘wild west’ gun market town

‘Men look beautiful with jewel of knowledge, beauty lies not in arms but in education’

https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/pakistan/library-thrives-in-pakista...

DARRA ADAMKHEL, Pakistan: When the din of Pakistan’s most notorious weapons market becomes overwhelming, arms dealer Mohammad Jahanzeb slinks away from his stall, past colleagues test-firing machine guns, to read in the hush of the local library.

“It’s my hobby, my favourite hobby, so sometimes I sneak off,” the 28-year-old told AFP after showing off his inventory of vintage rifles, forged assault weapons and a menacing array of burnished flick-knives.

“I’ve always wished that we would have a library here, and my wish has come true.”

The town of Darra Adamkhel is part of the deeply conservative tribal belt where decades of militancy and drug-running in the surrounding mountains earned it a reputation as a “wild west” waypoint between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

It has long been known for its black market bazaars stocked with forged American rifles, replica revolvers and rip-off AK-47s.

But a short walk away a town library is thriving by offering titles including Virginia Woolf’s classic “Mrs Dalloway”, instalments in the teenage vampire romance series “Twilight”, and “Life, Speeches and Letters” by Abraham Lincoln.

“Initially we were discouraged. People asked, ‘What is the use of books in a place like Darra Adamkhel? Who would ever read here?’” recalled 36-year-old founder Raj Mohammad.

“We now have more than 500 members.”

Tribal transformation

Literacy rates in the tribal areas, which were semi-autonomous until 2018 when they merged with the neighbouring province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, are among the lowest in Pakistan as a result of poverty, patriarchal values, inter-clan conflicts and a lack of schools.

But attitudes are slowing changing, believes soft-spoken 33-year-old volunteer librarian Shafiullah Afridi: “Especially among the younger generation who are now interested in education instead of weapons.”

“When people see young people in their neighbourhood becoming doctors and engineers, others also start sending their children to school,” said Afridi, who has curated a ledger of 4,000 titles in three languages - English, Urdu and Pashto.

Despite the background noise of gunsmiths testing weapons and hammering bullets into dusty patches of earth nearby, the atmosphere is genteel as readers sip endless rounds of green tea while they muse over texts.

However, Afridi struggles to strictly enforce a “no weapons allowed” policy during his shift.

One young arms dealer saunters up to the pristinely painted salmon-coloured library, leaving his AK-47 at the door but keeping his sidearm strapped on his waist, and joins a gaggle of bookworms browsing the shelves.

Alongside tattered Tom Clancy, Stephen King and Michael Crichton paperbacks, there are more weighty tomes detailing the history of Pakistan and India and guides for civil service entrance exams, as well as a wide selection of Islamic teachings.

‘Education not arms’

Libraries are rare in Pakistan’s rural areas, and the few that exist in urban centres are often poorly stocked and infrequently used.

In Darra Adamkhel, it began as a solitary reading room in 2018 stocked with Mohammad’s personal collection, above one of the hundreds of gun shops in the central bazaar.

“You could say we planted the library on a pile of weapons,” said Mohammad - a prominent local academic, poet and teacher hailing from a long line of gunsmiths.

Jan 21, 2023

Riaz Haq

Library thrives in Pakistan’s ‘wild west’ gun market town

‘Men look beautiful with jewel of knowledge, beauty lies not in arms but in education’

https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/pakistan/library-thrives-in-pakista...

Mohammad paid 2,500 rupees ($11) for the monthly rent, but bibliophiles struggled to concentrate amidst the whirring of lathes and hammering of metal as bootleg armourers plied their trade downstairs.

The project swiftly outgrew the confines of a single room and was shifted a year later to a purpose-built single-storey building funded by the local community on donated land.

“There was once a time when our young men adorned themselves with weapons like a kind of jewellery,” said Irfanullah Khan, 65, patriarch of the family who gifted the plot.

“But men look beautiful with the jewel of knowledge, beauty lies not in arms but in education,” said Khan, who also donates his time alongside his son Afridi.

For the general public a library card costs Rs150 rupees ($0.66) a year, while students enjoy a discount rate of 100 rupees ($0.44), and youngsters flit in and out of the library even during school breaks.

One in 10 members are female - a figure remarkably high for the tribal areas - though once they reach their teenage years and are sequestered in the home male family members collect books on their behalf.

Nevertheless, on their mid-morning break schoolgirls Manahil Jahangir, nine, and Hareem Saeed, five, join the men towering over them as they pore over books.

“My mother’s dream is for me to become a doctor,” Saeed says shyly. “If I study here I can make her dream come true.”

Jan 21, 2023

Riaz Haq

Bearing gifts: the camels bringing books to Pakistan’s poorest children

The mobile library services are an education lifeline for students in Balochistan, where schools have closed during the pandemic

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/apr/26/bearing-...

Sharatoon had wanted to continue her studies, but she had to leave school and her beloved books when she got married aged 15.

Now 27, Sharatoon is happy reading again, as every Friday a camel visits her small town, his saddle panniers full of books.

She has four children, the eldest is 11, the youngest 18 months, and she reads to them all, as well as to other children in the town.

Every week, when Roshan the camel comes to her home in Mand, about 12 miles from the border with Iran, in Pakistan’s Balochistan province, Sharatoon exchanges the books she borrowed for new ones.

“When the camel came to our area for the first time, the kids were very happy and excited. Schools have long been closed in our area due to Covid and we do not have any libraries, so this was welcomed by all the kids,” says Sharatoon, who uses only one name.

Balochistan is Pakistan’s most impoverished province, blighted by a separatist insurgency for the past two decades. With a 24% female literacy rate, one of the lowest in the world, compared with a male literacy rate of 56%, it also has the highest percentage of children out of school in the country.

Roshan visits four villages, staying in each at the home of a “mobiliser” such as Sharatoon, where all the district children aged four to 16 can come to read, borrow and exchange books with one another.

“Parents and kids are excited. It is giving hope to many that they can read, and the staff members also work on mobilisation so more outreach can be done,” says Fazul Bashir, a coordinator for the library.

When Covid closed the schools across Balochistan, two women in Mand – Zubaida Jalal, a federal minister in the Pakistan government, and her sister Rahima Jalal, headteacher of a local high school – came up with the idea of a camel.

“Actually, the idea of using camels comes from Mongolia and Ethiopia,” says Rahima. “It suits our desolate, distant and rough terrains. We have received an enormous response that we were not expecting.”

The trial of the camel library has gone well and it is about to begin its next three months of rounds.

Sharatoon says: “Kids are eagerly waiting; they want to read books and keep asking me [about it]. There should be more science-related books so our kids can learn by experimentation.”

The Jalal sisters say there has been a lot of interest in the scheme from other areas, and they have just started a library in the city district of Gwadar, Balochistan, with a camel called Chirag.

Anas Syed Mohammad is a 10-year-old 4th-grade student in the town of Abdul Rahim Bazar, about 30 miles from the city of Gwadar.

Since the camel library started visiting three weeks ago, Mohammad has read a different book each time. “I loved reading Khazane Ki Talaash (In Search of Treasure). I discuss these books with my friends,” he says.

Jan 21, 2023

Riaz Haq

Bearing gifts: the camels bringing books to Pakistan’s poorest children

The mobile library services are an education lifeline for students in Balochistan, where schools have closed during the pandemic

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/apr/26/bearing-...

Chirag visits five towns each week accompanied by his handler and Ismail Yaqoob, a volunteer and teacher. One day, when Yaqoob went to work in his school instead of the village, he got a call on his mobile from one of the children.

“He asked me why I had not come along with the camel. They were waiting for books,” says Yaqoob. “Children are so interested in reading and in their studies, but sadly the state does not invest in education.”

Jawad Ali, 10, who has ambitions to be a teacher, has also started borrowing books from the camel library. He says: “I am learning new things from these books and reading stories, understanding photo stories. But I want to read more books. The books are written in my native language – Balochi – but in English and Urdu as well. We want more books – and libraries and schools, too.”

Jan 21, 2023

Riaz Haq

Monthly December 2022

ECONOMIC UPDATE & OUTLOOK Pakistan

https://www.finance.gov.pk/economic/economic_update_December_2022.pdf

The government has decided to include

transgenders in the Benazir Kafalat

programme for the first time to mobilize

this marginalized community, so that the

maximum number of transgender

persons could benefit from this policy.

PPAF through its 24 Partner

Organizations has disbursed 41,369

interest free loans amounting to Rs 1.70

billion during the month of November,

2022. Since inception of interest free loan

component, a total of 2,142,190 interest

free loans amounting to Rs 78.54 billion

have been disbursed to the borrowers.

During January-November 2022 Bureau

of Emigration and Overseas Employment

has registered 762,767 emigrants and

71055 emigrants during November, 2022

for overseas employment in different

countries.

According to WHO, cases of malaria,

cholera, acute watery diarrheal diseases,

and dengue fever are declining in most of

the flood-affected districts. Overall,

malaria cases have reduced to around

50,000 from over 100,000 confirmed

cases in early October. Malaria cases

have declined by 25% in Balochistan, 58%

in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and 67% in

Sindh provinces. However, high malaria

and cholera cases are still being reported

in some pocket districts in Sindh and

Balochistan where standing water

remains. In November 2022, around 70

suspected cases of Diphtheria were

reported from the flood-affected

provinces of KP, Sindh, and Punjab.

There are about 1.6 million children with

Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) across

all the flood-affected districts who need

treatment with Ready to Use Therapeutic

Food (RUTF). About 400,000 of these

children are in the 34 Government High

Priority Districts (GHPD). Bridging the

nutrition budget gap for an aggressive

sector-wide response is therefore very

critical. (OCHA, Flood situation report on

Pakistan, December, 06, 2022).

Jan 25, 2023

Riaz Haq

Monthly December 2022

ECONOMIC UPDATE & OUTLOOK Pakistan

https://www.finance.gov.pk/economic/economic_update_December_2022.pdf

Real Sector:

For Rabi season 2022-23, wheat crop

has been sown on an area of 20.77

million acres . The input situation is 1

expected to remain favorable due to

incentives announced in Kissan Package

2022 that will boost agriculture

productivity. The better input situation is

expected to increase crops production in

Rabi season. According to IRSA the

irrigation water supply recorded at 6.32

MAF for November 2022 against the last

year's supply of 5.50 MAF, increased by

0.82 MAF.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) recorded

at 23.8 percent on a YoY basis in

November 2022 as compared to 26.6

percent in the previous month

Jan 25, 2023

Riaz Haq

Pakistan launches ‘School on Wheels’ project to improve education in rural areas

https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/pakistan/pakistan-launches-school-o...

8 mobile classrooms will provide primary-level education and offer libraries and meals

Islamabad: Pakistan government launched the ‘School on Wheels’ project to being education to the doorstep of children whose parents are unable to send them to school.

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif launched the initiative on Tuesday and expressed hopes that the initiative would increase the literacy rate in Pakistan, particularly in rural areas. During the inauguration of mobile schools, PM Sharif said that the project aims to offer equal educational opportunities to children in rural areas who lacked the availability of modern educational facilities.

The prime minister also interacted with the schoolchildren at the launch ceremony. He urged the kids to utilise mobile libraries and hoped that it would promote a reading culture among the children. Education Minister Rana Tanveer Hussain briefed the prime minister on various features of the project. He said that in addition to mobile libraries, the project would also provide meals to the students enrolled in mobile classrooms, fostering a culture of reading and nourishment.

Eight mobile school buses

The bright-coloured buses were decorated with balloons and the windows were painted with alphabets and cartoons. The inside of the mobile classrooms is bright and clean, its interior filled with images of alphabets, numbers, days of the week, and pictures of fruit and animals. On the first day, children were seen sitting on colorful chairs inside the bus as a teacher used the interactive whiteboard for teaching.

Initially, the mobile school project consists of eight buses that will provide primary-level education to the children of Islamabad and nearby areas. Each bus is equipped with computers, desks, whiteboards, and LCDs. The government plans to increase the number of buses and expand the project to the rest of the country.

The ‘school on wheels’ project aims to bring education to the doorstep of disadvantaged children to give them a chance to learn. Several similar mobile school projects have been earlier introduced in Pakistan by public and private organisations.

Feb 28, 2023

Riaz Haq

The PIDE report further states that by breaking down the data further, it was discovered that approximately 1 in 4 (23.45 percent) children between the ages of 5–16 in Pakistan had never attended school whereas about 7 percent had enrolled and dropped out.

https://www.nation.com.pk/07-Mar-2022/22-8m-children-between-5-16-y...

Pakistan has the world’s second-highest number of out-of-school children where an estimated 22.8 million children between 5 to 16 years of age are not attending school representing 44pc of the total population in this age group.

The proportion of children out-of-school between the ages 5-16 stood at a whopping 30pc nationwide in 2018-19, with Balochistan, the worst performing province, where 59pc approximately 2 out of 3 children are deprived of basic education, followed by Sindh with 42pc percent out of school Children, revealed in a recent research report of the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) titled ‘Primary School Literacy: A Case Study Of The Educate A Child Initiative.’ In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the merged areas there are 31pc out of school children, the report added.

Pakistan is facing a serious challenge to ensure all children, particularly the most disadvantaged, attend, stay and learn in school. While enrolment and retention rates are improving, progress has been slow on improving educational indicators in Pakistan. According the report nearly 10.7 million boys and 8.6 million girls are enrolled at the primary level which drops to 3.6 million boys and 2.8 million girls at the lower secondary level.

The report states that according to the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM)’s survey conducted during 2018-19, approximately 51 percent of the population of Pakistan has successfully completed their primary level education which rose 2pc from 2013-14. Balochistan was the worst performing province in this regard, with figures actually declining from 33pc in 2013-14 to 31 percent in 2018-19–the COVID-19 pandemic has likely caused further damage.

Punjab, on the other hand, was the best performing province with a completion rate of just 57pc, approximately 3 out of 5. Assuming that education and literacy are public goods, these statistics indicate a looming crisis for Pakistan which has not managed to formulate a comprehensive strategy or framework around which children may become literate and empower themselves economically.

PIDE report says 59pc children in Balochistan deprived of basic education

The PIDE report further states that by breaking down the data further, it was discovered that approximately 1 in 4 (23.45 percent) children between the ages of 5–16 in Pakistan had never attended school whereas about 7 percent had enrolled and dropped out.

The situation in Balochistan and Sindh was the worst. In the former, about half of children in the same age bracket had never attended school (54.25pc) and in the latter, the figure stood at 35.44pc.

The report mentioned that alongside enrolment, there was a grave need to address the shortcomings of the system in place responsible for supporting and overseeing public schools.

These institutions have historically struggled to address problems such as teacher absenteeism, low enrolment, high dropout, and poor physical conditions. The reason for this is a lack of resources and underdeveloped monitoring/governance mechanisms—along with the absence of any substantial coordination mechanisms.

According to the PIDE’s report there is a need for the establishment of local, grassroots level entities that could act as intermediaries between targeted populations and the governing agencies.

The report emphasised that gaps in service provision at all education levels are a major constraint to education access. Socio-cultural demand-side barriers combined with economic factors and supply-related issues (such as availability of school facilities), together hamper access and retention of certain marginalized groups, in particular adolescent girls. Putting in place a credible data system and monitoring measures to track retention and prevent drop-outs of out-of-school children is still a challenge.

At the systems level, inadequate financing, limited enforcement of policy commitments, and challenges inequitable implementation impede reaching the most disadvantaged. An encouraging increase in education budgets has been observed at 2.8pc of the total GDP, it is still well short of the 4pc target, the report added.

Feb 28, 2023

Riaz Haq

Primary School Literacy: A Case Study of the Educate a Child Initiative

Abbas Moosvi, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

https://pide.org.pk/research/primary-school-literacy-a-case-study-o...

INTRODUCTION

According to the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement survey of 2018-19, approximately 51 percent of the population of Pakistan has successfully completed their primary level education – a figure that rose 2 percent from 2013-14. Balochistan was the worst performing province in this regard, with figures actually declining from 33 percent in 2013-14 to 31 percent in 2018-19—and the COVID-19 pandemic has likely caused further damage. Punjab, on the other hand, was the best performing, with a completion rate of just 57 percent—approximately 3 out of 5. Assuming that education and literacy are public goods, these statistics indicate a looming crisis for Pakistan: which has not managed to formulate a comprehensive strategy or framework around which children may become literate and empower themselves economically.

OUT-OF-SCHOOL CHILDREN: A CRISIS OF POLICY

The proportion of children out-of-school between the ages 5-16 stood at a whopping 30 percent nationwide in 2018-19. In Balochistan, the worst performing province, the figure stood at 59 percent during the same period: approximately 3 out of 2 children deprived of basic education. In Sindh, the rate was 42 percent—alarming for the province generating the highest tax revenues in the country, largely from the economic capital: Karachi.

Breaking down the data further, it was discovered that approximately 1 in 4 (23.45 percent) children between the ages of 5–16 in Pakistan had never attended school—whereas about 7 percent had enrolled and dropped out. The situation in Balochistan and Sindh was the worst. In the former, about half of children in the same age bracket had never attended school (54.25 percent) and in the latter the figure stood at 35.44 percent.

Feb 28, 2023

Riaz Haq

How Maqsad’s Mobile Education Can Help More Pakistani Students Learn

https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidprosser/2023/03/16/how-maqsads-mo...