PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

Pakistan-born, Harvard-educated economist Ms. Saadia Zahidi, author of "50 Million Rising", is currently a member of the executive committee and the head of Education, Gender and Work at the World Economic Forum, Davos, Switzerland. She told Kai Ryssdal of APR Marketplace of her visit to a gas field in Pakistan with her geophysicist father where she met Nazia, a woman engineer who inspired her.

|

| Saadia Zahidi |

The "50 Million" in the title of her book refers to the 50 million Muslim women who have joined the work force over the last 15 years bringing the total number of working women in the Muslim world to about 155 million.

In her book, Saadia talks about her father being the first in his family to go to university. He believed in girls' education and career opportunities. She recalls him suggesting that "my sister could become a pilot because the Pakistan Air Force had just starting to train women. Another time he speculated that I could become a news anchor because Pakistan Television, the state-owned television network, had started recruiting more women". Here's an excerpt of her book:

"This shift has not been limited to Pakistan. A quiet but powerful tsunami of working women has swept across the Muslim world. In all, 155 million women work in the Muslim world today, and fifty million of them--a full third--have joined the work force since the turn of the millennium alone, a formidable migration from home to work in the span of less than a generation".

Saadia Zahidi has devoted parts of her book to her experiences in Pakistan where she visited a McDonald's restaurant and found many women working there. A woman also named Saadia working at McDonald's restaurant in Rawalpindi is featured in the book. Here's an excerpt:

"For young women like Saadia, seeing their efforts rewarded in the workplace, just as they were in school and university, can be eye-opening and thrilling and lead them to become even more motivated to work. The independent income is an almost unexpected bonus. I asked Saadia how she spends her earnings and whether she saves. She gives 30 percent of her income to her parents, she said, and the rest she spends as she pleases: mostly on gifts to her parents, sisters, and friends as well as on lunches and dinners out with friends and gadgets like her cell phone—all new luxuries for her. She said that she has no interest in saving because her parents take care of housing and food, just as she expects her husband will do after she marries. So her disposable income is wholly hers to spend, allowing her to contribute to the household budget while also buying luxuries that were previously unimaginable for her parents, without adding a burden to them."

Challenging the stereotypes about Muslim women, Saadia cites an interesting statistic: In Saudi Arabia, out of all of the women that could be going to university, 50 percent are. And that is higher than in China, in India, in Mexico, in Brazil.

I wrote a post titled "Working Women Seeding a Silent Revolution in Pakistan" in 2011. It's reproduced below in full:

While Fareed Zakaria, Nick Kristoff and other talking heads are still stuck on the old stereotypes of Muslim women, the status of women in Muslim societies is rapidly changing, and there is a silent social revolution taking place with rising number of women joining the workforce and moving up the corporate ladder in Pakistan.

"More of them(women) than ever are finding employment, doing everything from pumping gasoline and serving burgers at McDonald’s to running major corporations", says a report in the latest edition of Businessweek magazine.

Beyond company or government employment, there are a number of NGOs focused on encouraging self-employment and entrepreneurship among Pakistani women by offering skills training and microfinancing. Kashf Foundation led by a woman CEO and BRAC are among such NGOs. They all report that the success and repayment rate among female borrowers is significantly higher than among male borrowers.

In rural Sindh, the PPP-led government is empowering women by granting over 212,864 acres of government-owned agriculture land to landless peasants in the province. Over half of the farm land being given is prime nehri (land irrigated by canals) farm land, and the rest being barani or rain-dependent. About 70 percent of the 5,800 beneficiaries of this gift are women. Other provincial governments, especially the Punjab government have also announced land allotment for women, for which initial surveys are underway, according to ActionAid Pakistan.

Both the public and private sectors are recruiting women in Pakistan's workplaces ranging from Pakistani military, civil service, schools, hospitals, media, advertising, retail, fashion industry, publicly traded companies, banks, technology companies, multinational corporations and NGOs, etc.

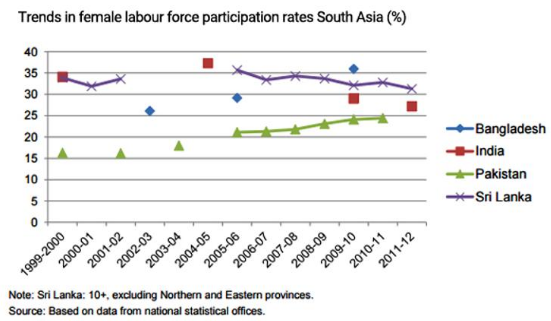

Here are some statistics and data that confirm the growth and promotion of women in Pakistan's labor pool:

1. A number of women have moved up into the executive positions, among them Unilever Foods CEO Fariyha Subhani, Engro Fertilizer CFO Naz Khan, Maheen Rahman CEO of IGI Funds and Roshaneh Zafar Founder and CEO of Kashf Foundation.

2. Women now make up 4.6% of board members of Pakistani companies, a tad lower than the 4.7% average in emerging Asia, but higher than 1% in South Korea, 4.1% in India and Indonesia, and 4.2% in Malaysia, according to a February 2011 report on women in the boardrooms.

3. Female employment at KFC in Pakistan has risen 125 percent in the past five years, according to a report in the NY Times.

4. The number of women working at McDonald’s restaurants and the supermarket behemoth Makro has quadrupled since 2006.

5. There are now women taxi drivers in Pakistan. Best known among them is Zahida Kazmi described by the BBC as "clearly a respected presence on the streets of Islamabad".

6. Several women fly helicopters and fighter jets in the military and commercial airliners in the state-owned and private airlines in Pakistan.

Here are a few excerpts from the recent Businessweek story written by Naween Mangi:

About 22 percent of Pakistani females over the age of 10 now work, up from 14 percent a decade ago, government statistics show. Women now hold 78 of the 342 seats in the National Assembly, and in July, Hina Rabbani Khar, 34, became Pakistan’s first female Foreign Minister. “The cultural norms regarding women in the workplace have changed,” says Maheen Rahman, 34, chief executive officer at IGI Funds, which manages some $400 million in assets. Rahman says she plans to keep recruiting more women for her company.

Much of the progress has come because women stay in school longer. More than 42 percent of Pakistan’s 2.6 million high school students last year were girls, up from 30 percent 18 years ago. Women made up about 22 percent of the 68,000 students in Pakistani universities in 1993; today, 47 percent of Pakistan’s 1.1 million university students are women, according to the Higher Education Commission. Half of all MBA graduates hired by Habib Bank, Pakistan’s largest lender, are now women. “Parents are realizing how much better a lifestyle a family can have if girls work,” says Sima Kamil, 54, who oversees 1,400 branches as head of retail banking at Habib. “Every branch I visit has one or two girls from conservative backgrounds,” she says.

Some companies believe hiring women gives them a competitive advantage. Habib Bank says adding female tellers has helped improve customer service at the formerly state-owned lender because the men on staff don’t want to appear rude in front of women. And makers of household products say female staffers help them better understand the needs of their customers. “The buyers for almost all our product ranges are women,” says Fariyha Subhani, 46, CEO of Unilever Pakistan Foods, where 106 of the 872 employees are women. “Having women selling those products makes sense because they themselves are the consumers,” she says.

To attract more women, Unilever last year offered some employees the option to work from home, and the company has run an on-site day-care center since 2003. Engro, which has 100 women in management positions, last year introduced flexible working hours, a day-care center, and a support group where female employees can discuss challenges they encounter. “Today there is more of a focus at companies on diversity,” says Engro Fertilizer CFO Khan, 42. The next step, she says, is ensuring that “more women can reach senior management levels.”

The gender gap in South Asia remains wide, and women in Pakistan still face significant obstacles. But there is now a critical mass of working women at all levels showing the way to other Pakistani women.

I strongly believe that working women have a very positive and transformational impact on society by having fewer children, and by investing more time, money and energies for better nutrition, education and health care of their children. They spend 97 percent of their income and savings on their families, more than twice as much as men who spend only 40 percent on their families, according to Zainab Salbi, Founder, Women for Women International, who recently appeared on CNN's GPS with Fareed Zakaria.

Here's an interesting video titled "Redefining Identity" about Pakistan's young technologists, including women, posted by Lahore-based 5 Rivers Technologies:

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Status of Women in Pakistan

Microfinancing in Pakistan

Gender Gap Worst in South Asia

Status of Women in India

Female Literacy Lags in South Asia

Land For Landless Women

Are Women Better Off in Pakistan Today?

Growing Insurgency in Swat

Religious Leaders Respond to Domestic Violence

Fighting Agents of Intolerance

A Woman Speaker: Another Token or Real Change

A Tale of Tribal Terror

Mukhtaran Mai-The Movie

World Economic Forum Survey of Gender Gap

Riaz Haq

#Pakistan appoints first-ever female diplomat at its embassy in #SaudiArabia

https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/308165-pakistan-appoints-first-ev...

Fouzia Fayyaz has been appointed as councilor at Pakistan’s embassy in Saudi Arabia, making her the first-ever female diplomat in the Kingdom in 70 years.

Talking to Daily Jang, Fouzia stated that Pakistan is a progressive country that has always recognised the potential and status of women as they continue to excel in their respective fields. The foreign ministry has always taken initiatives to broaden opportunities of success for women, she further added.

She also said that with her appointment more and more women have now been inducted at the section of the embassy of which she is in-charge.

According to Fouzia, her determination to soar to new heights stems from the fact that she had a very supporting father who gave equal importance to education of girls as boys. Hailing from southern Punjab, Fouzia acquired a Master’s degree in English Literature from Islamia University in Bahawalpur after which she gave her CSS exams.

He first appointment was in Washington D.C and then in New Delhi where she also rendered services as diplomat.

Apr 23, 2018

Riaz Haq

Pakistan’s Gig Economy Helps Smash Obstacles To Women Working

In a country with one of the lowest rates of female participation in the labor market, the digital economy is enabling some women to become breadwinners

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/gig-economy-pakistan_us_5ad9e8...

When 28-year-old Dr. Aqsa Sultan was nine months pregnant with her first child, she decided to leave her job at a cardiology institute in Pakistan’s port city of Karachi to be a stay-at-home mom.

But she felt a twinge of resentment watching her husband, also a doctor, go to work each day to treat patients. “I was going through an identity crisis,” Sultan says. “After a while, I got fed up and I wanted to do something to be back in the field.

Sultan found a way to practice medicine from home. DoctHERs, a telemedicine platform in Pakistan, connects unemployed or underemployed female doctors like Sultan to patients in remote areas. Despite having one of the lowest doctor-to-patient ratios in the world, pressure to prioritize families over careers means that around half of female medical school graduates never enter the workforce.

For those who do overcome myriad obstacles to practice medicine, many drop out of the labor force when they are married or have children. DoctHERs is “about them being able to participate in the workforce and feel a sense of autonomy,” says Asher Hasan, the organization’s co-founder.

Pakistan has one of the world’s lowest rates of female participation in the labor market — it is estimated only 25 percent of women over the age of 15 work. However, there are signs that technology is gradually transforming women’s participation in some areas of the labor force.

Pakistan accounts for 8 percent of the worldwide digital gig economy, trailing only India, Bangladesh and the United States. The rise of gig work (flexible, piecemeal jobs), say some experts, has provided many Pakistani women a foothold in the new digital economy, in some cases shifting women into the primary breadwinner role.

“The gig economy is a unique economic opportunity for women in Pakistan... allowing women to earn a living or access a service from the home when cultural constraints may not allow them to work outside the home,” says Saadia Zahidi, author of Fifty Million Rising: The New Generation of Working Women Transforming the Muslim World.

Sultan normally works in the evenings, when her husband can take over childcare. She selects the number of days and hours she works, and gets paid per video consultation. “They can switch their availability on and off,” adds DoctHERs’ Hasan. “They get to decide their own hours.”

May 1, 2018

Riaz Haq

Pakistan footballer Hajra Khan: ‘It’s changing. Slowly, but it’s changing’

The captain of the Pakistan women’s team is challenging preconceptions in her homeland and beyond as she leads a fight for equality and recognition

https://www.theguardian.com/football/2018/may/18/pakistan-hajra-kha...

Karachi is the capital of the province of Sindh, the most populous city in Pakistan and among the biggest in the world. Bordering the Arabian Sea, it is home to more than 21 million people.

Here football is the opiate of the people. It comes as no surprise that Hajra Khan first played outside her home with other children, keeping goal in a net chalked out against a neighbouring wall. However, it was not until she was 14, preoccupied with basketball and track and field, that her mother came across football tryouts in the local Sunday paper and told her to give it a shot.

Ten years on, Khan’s talent has forced football to transcend the country’s historically rigid gender norms and has proved to be a vehicle for change. Khan was made captain of the Pakistan women’s team at the age of 20. She is the country’s highest-scoring female footballer, a Unicef ambassador and the first Pakistani player, male or female, to be signed by a foreign club.

As a child Khan was quiet but she has been anything but when it comes to her national team’s struggle for equality. At the most recent training camp the women were paid $3 a day to the men’s $10. “Dentists, economists, engineers and school girls quit their livelihoods just to be at that camp, a camp that pays a quarter of what they were earning,” Khan says.

Demands from the women’s team for more appear to have had an impact. It was announced in April that the wage would be increased to $10 a day – although the men’s pay was doubled to $20. Khan’s fight is part of a global picture, with female footballers across the US, Norway, Brazil, Ireland and most recently New Zealand demanding gender parity.

Though there is no ignoring the signs of progress in Pakistan, with a historic transgender rights bill passed this month, sexism is pervasive in the Islamic country – which gained notoriety for arguably being one of the most oppressive countries for women, ranking second-worst on the Global Gender Gap index. Men’s teams are not only paid more but granted priority in pitch bookings over women’s teams, who then have to train on cricket pitches or any surface that suffices. And the problems run deeper.

“Say if there’s a photo with the national team on Facebook, there’s going to be 100 negative comments about how she’s not Muslim, how she’s a disgrace to the country,” Khan says. “They don’t care of the skill that the girl has, or the credibility that she holds, or that she’s representing the national team.”

May 19, 2018

Riaz Haq

Why the new global wealth of educated women spurs backlash

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/why-the-new-global-wealth-of-educ...

The spread of education across developing nations is transforming global inequalities and playing a key role in closing the gender gap. Economics correspondent Paul Solman sits down with economist Surjit Bhalla and sociologist Ravinder Kaur to discuss Bhalla’s book, “The New Wealth of Nations,” as well as the backlash to increasing equality.

Paul Solman:

Indian economist Surjit Bhalla and his wife, sociologist Ravinder Kaur, in the U.S. recently to spread the message of “The New Wealth of Nations.”

Surjit Bhalla:

The key thesis of the book is that education and the spread of education has transformed the world and has transformed relationships, inequalities between countries and, finally and most importantly, between the sexes.

Paul Solman:

And the cost? What’s the cost?

Surjit Bhalla:

The cost is that people in the West are going to lose out relative to the people in the East, the East meaning the rest of the world, the West meaning the advanced countries.

What happens, when the world is filled with everybody graduating from high school, then the Western people will lose their advantage over the rest of the world.

Paul Solman:

And so that’s why the person with a high school diploma in the United States has seen her or his, usually his, earnings…

Surjit Bhalla:

Decline, yes, in real terms, by something like 10 percent or 15 percent over the last 25 years. The real wage of those who went to college, but didn’t graduate has stayed the same. And the real wage of college graduates, the creme de la creme, has risen by only 0.5 percent per annum.

Paul Solman:

But it’s not the creme de la creme anymore, because you can go beyond college.

Surjit Bhalla:

Well, no, this includes beyond graduate. Whether it’s doctors or it’s lawyers, everything is transferable now.

Even surgery can be done transatlantic by the use of technology. Where is the real advantage left for an American or a British or German or Western professional?

Paul Solman:

Isn’t that why there’s a reaction against immigration?

Ravinder Kaur:

Yes.

You know, there’s always a scapegoat when things are not going well for you. And it always tends to be somebody we think of as the other. You know, it could be a person of a different color. It could be a person of different religious persuasion.

Surjit Bhalla:

Different sex.

Ravinder Kaur:

Of different sex or whatever. So, today, maybe men are resentful of women.

Surjit Bhalla:

Previously, there were always the bottom 20 percent who lost out, but they could come home and feel superior to or dominate their wives.

Now they come home, and the women are the major breadwinners, or are more educated than them, or more able than them.

Paul Solman:

Or at least are competing with them.

Surjit Bhalla:

Or competing. From where they were here, now they’re equals. That can mess up the psychology of men.

Ravinder Kaur:

I think it is a threatened masculinity issue. Why do you see more, you know, such crime in places where the gender gap is closing?

Paul Solman:

According to the World Health Organization, for example, violence against women surged in both Nicaragua and Uganda following public information campaigns promoting women’s rights.

And then there’s the so-called Nordic paradox. Though Iceland Norway, Finland and Sweden take the World Economic Forum’s global index of gender equality — the U.S. ranks 49th — they are also among the worst in Europe for domestic violence and sexual assault.

Ravinder Kaur:

So, for quite some time, my argument has been that if you see more violence and if you see more gender crime, it’s a backlash. How dare this woman be in the public space, and you know how dare she aspire…

Surjit Bhalla:

Be equal.

May 31, 2018

Riaz Haq

#Pakistani #women riding #motorcycles to fight patriarchy. #WomenatWork #Pakistan

http://www.latimes.com/world/la-fg-pakistan-women-motorcycle-201807...

One morning recently, 28-year-old Rahila Qaisar donned a pink helmet, balanced her handbag on her lap and revved her new pink Honda motorcycle, so fresh from the factory that the passenger seat was still covered in plastic.

Qaisar is one of hundreds of newly minted motorcycle riders zipping around eastern Pakistan under a government initiative to help women navigate the country’s notoriously male-dominated roads.

The Women on Wheels campaign has trained more than 3,500 female motorcycle riders in Punjab province — the country’s largest — and plans to furnish more than 700 subsidized bikes to licensed riders from low- and middle-income families.

The program represents a small revolution for women such as Qaisar, a bubbly preschool teacher who said that running even the most mundane errands — shuttling her father to appointments and zipping through the narrow lanes of busy shopping areas — has given her newfound self-confidence.

“It helps us economically and it helps us emotionally,” Qaisar said. “When I first started riding, I felt like I was flying high in the sky.”

A few years ago, when her parents were bedridden after a road accident, Qaisar wished she hadn’t been born a girl.

“I could have done more for my family as a son,” said Qaisar, the youngest of three daughters and the last one still living at home. To fetch medicines and household supplies, she crisscrossed this sprawling city alone in buses and motorized rickshaws, braving heat, traffic delays and unwanted attention from strange men.

Her father’s motorcycle — the preferred conveyance for Lahore’s harried working class — sat idle in the garage. It wasn’t considered proper for a woman in Pakistan to ride one.

While women in Saudi Arabia made headlines this summer for earning the right to drive for the first time, Pakistani women face a different struggle on the roads. Few families can afford cars. In Lahore, a provincial capital of 11 million people with an extensive road network but inadequate mass transit, riding public buses often means long wait times and crowded compartments where men can grope and harass female riders with impunity.

In Pakistan’s deeply patriarchal society — where fathers, brothers and husbands often dictate women’s movements — surveys show men strongly oppose female family members taking most forms of public transport. The Center for Economic Research in Pakistan has found that these restrictions constrain women from working, pursuing higher education and venturing beyond their neighborhoods.

“Economic empowerment is dependent on mobility, and this was the cheapest way we could give women mobility,” said Salman Sufi, head of the province’s Strategic Reforms Unit, which implemented the program. The bikes were painted pink to stand out — and discourage male relatives from using them.

When Qudsia Abbas received her bike — it retails for about $650, but the program offers a 40% discount — it was the most exciting development in her family in years. Her younger sisters, who had to beg their father to drop them off at tutoring sessions and school events on his motorbike, now rely on her for rides.

“I became a brother to my sisters,” said Abbas, 20, who has no male siblings. “My father is a lot more relaxed now.”

Kate Vyborny, a Duke University researcher who studies transportation in Pakistan, said Women on Wheels could help “shift the norms around women in public spaces” and fight the conservative stereotype that a woman straddling a motorcycle is somehow indecent.

But with initiatives such as women-only buses having had limited success, Vyborny said that officials should closely monitor the impact of such a significant cultural change.

“Generally it’s been taboo for women to ride motorbikes,” Vyborny said. “If the government is successful in increasing acceptance of that, it’s a really major thing.”

Jul 13, 2018

Riaz Haq

Justice Tahira Safdar nominated as first female chief justice in #Balochistan or anywhere else in #Pakistan. #judiciary #gender https://tribune.com.pk/story/1764871/1-justice-tahira-safdar-nomina...

Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP) Mian Saqib Nisar on Monday nominated Justice Syeda Tahira Safdar as the Chief Justice of Balochistan High Court (BHC), paving way for her to become the first female chief justice of any court in the country.

“Madam Tahira Safdar will be the next chief justice of BHC,” he announced at Justice Safdar’s book launch in Lahore, where he was invited as the chief guest.

Speaking on the occasion, Justice Nisar said that he will never even let a scratch come to the institution, referring to the matter of Justice Siddiqui’s fiery speech against state institutions.

“Unfortunately, a few forces are trying to undermine and weaken the judiciary, I will never let that happen,” he remarked. “As long as the Supreme Court exists, no threats against democracy will succeed.”

BHC’s incumbent Chief Justice Muhammad Noor Meskanzai is scheduled to retire on September 1 this year. He was sworn in on December 26, 2014 after Justice Qazi Faez Isa was elevated as a Supreme Court judge.

Justice Tahira Safdar will work as the chief justice of the BHC till October 5 next year. Justice Tahira Safdar is part of the special court, hearing the high treason case against former military ruler Pervez Musharraf.

Interestingly, Justice Safdar was the first woman to be appointed as a civil judge in Balochistan, besides having the distinction of being the first lady to be appointed in all posts she served. She was also the first female high court judge.

According to her profile on BHC’s website, Justice Safdar is the daughter of Syed Imtiaz Hussain Baqri Hanafi, a renowned lawyer.

She was born on October 5, 1957, at Quetta. She received her basic education from the Cantonment Public School, Quetta, and finished her bachelors’ degree from the Government Girls College, Quetta. Justice Syeda Tahira Safdar did her Masters in Urdu Literature from the University of Balochistan, and completed her degree in law from the University Law College, Quetta, in 1980.

Jul 23, 2018

Riaz Haq

#Pakistan's first woman ambassador to #Iran takes charge in #Tehran

https://nation.com.pk/07-Aug-2018/pakistan-s-first-woman-envoy-to-i...

Ambassador Riffat Masood on Tuesday presented her credentials to Iran’s Foreign Minister Jawad Zareef, becoming the country’s first woman envoy to Iran.

Riffat Masood is a career diplomat with wide experience of diplomacy and having fluency in Persian language.

She also had various diplomatic assignments in the country’s missions in Norway, United Kingdom, the United States, Turkey and France.

Aug 7, 2018

Riaz Haq

Charted: The shocking gender divide in India’s workforce

https://qz.com/india/1404730/the-shocking-gap-between-indias-male-a...

From wage gaps to social prejudices, Indian women face multiple barriers to entering the workforce in greater numbers.

“The Indian economy remains heavily gender segregated,” a report by the Bengaluru-based Azim Premji University’s Centre for Sustainable Employment (pdf) has found. The report on India’s job market also underscores the fact that women haven’t completely benefited from India’s rapid economic progress.

India’s female labour-force participation is among the lowest in the world and what is worse, it has only stagnated in the last decade. This has been attributed to factors such as societal attitudes that give preference to early marriages over jobs and education, a general disapproval of working women, and a lack of suitable job opportunities for them. Women also continue to be employed mostly in low-paying, low-value jobs.

Here’s how India’s women stack up in the workforce.

How much do they make

The wage gap, much like the world over, persists in the Indian job market, too. And for women here, who are largely employed in low value-added sectors such as agriculture, textiles, and domestic services, the wage disparity is quite striking. “Women earn between 35% and 85% of men’s earnings, depending on the type of work and the level of education of the worker,” the report added.

However, over the last few years, pay disparities have reduced across certain sectors.

For instance, in the organised manufacturing sector, the pay gap has narrowed from 35% in 2000 to 45% in 2013. Similarly, the report noted a reduction in the earnings gap in female-dominated industries like food, tobacco, textiles, apparel, and among construction labourers.

Where do they work

Women in India form a large chunk of the workforce in industries such as agriculture, education, and textiles. “Women workers remain highly over-represented in the low value-added industries as well as occupations, such as agriculture, textiles, and domestic service,” the report noted. These low-value-added industries mean that women continue to be on the lower end of the pay scale.

At the higher end of the wage spectrum, women are few in number. “Women continue to be heavily under-represented among senior officers, legislators and managers…Also, on a negative note, women continue to be over-represented in elementary occupations, which are among the least well-paid,” the report noted.

The silver lining, though, is that the winds of change have started to blow. More and more educated women are joining higher-earning occupations, even though their share remains small.

With the generally better level of education, there has been an increase in the share of women working as accountants, auditors, market research analysts, public relations personnel, and financial analysts. This means that there is a small but steady rise in women with high-paying jobs. “Women are even over-represented among associate-level professionals. Further, the share of women working in these well-paying occupations has increased steadily since 1994.”

Even as the country grapples with providing meaningful employment to its young people, policies directed towards enabling more women to join the workforce could bode well for the country.

The report noted that despite the proliferation of jobs in the economy, India has done little to create more opportunities for women. “Broadly speaking, economic growth in India has still not generated a process of employment diversification, especially for women.”

Sign up for the Quartzy email

TAGS

jobs, india, agriculture, ilo, women in workforceIndia’s supreme court strikes down a colonial-era adultery law

Sep 30, 2018

Riaz Haq

#Female car mechanic driving change in patriarchal #Pakistan. She has also convinced some of those who doubted her ability to make it in a male-dominated work environment, including members of her own family. #automobile #technician

https://www.khaleejtimes.com/international/pakistan/female-car-mech...

Since picking up a wrench as one of the first female car mechanics in conservative Pakistan, Uzma Nawaz has faced two common reactions: shock and surprise. And then a bit of respect.

The 24-year-old spent years overcoming entrenched gender stereotypes and financial hurdles en route to earning a mechanical engineering degree and netting a job with an auto repairs garage in the eastern city of Multan.

"I took it up as a challenge against all odds and the meagre financial resources of my family," Nawaz told AFP.

"When they see me doing this type of work they are really surprised."

Hailing from the small, impoverished town of Dunyapur in eastern Pakistan's Punjab province, Nawaz relied on scholarships and often skipped meals when she was broke while pursuing her degree.

Her achievements are rare. Women have long struggled for their rights in conservative patriarchal Pakistan, and especially in rural areas are often encouraged to marry young and devote themselves entirely to family over career.

"No hardship could break my will and motivation," she says proudly.

The sacrifices cleared the way for steady work at a Toyota dealership in Multan following graduation, she adds.

Just a year into the job, and promoted to general repairs, Nawaz moves with the ease of a seasoned pro around the dealership's garage, removing tyres from raised vehicles, inspecting engines and handling a variety of tools - a sight that initially jolted some customers.

"I was shocked to see a young girl lifting heavy spare tyres and then putting them back on vehicles after repairs," customer Arshad Ahmad told AFP.

But Nawaz's drive and expertise have impressed colleagues, who say she can more than hold her own.

"Whatever task we give her she does it like a man with hard work and dedication," said co-worker M. Attaullah.

She has also convinced some of those who doubted her ability to make it in a male-dominated work environment, including members of her own family.

"There is no need in our society for girls to work at workshops, it doesn't seem nice, but it is her passion," said her father Muhammad Nawaz.

"She can now set up the machinery and can work properly. I too am very happy."

Oct 16, 2018

Riaz Haq

FROM FIRST PAKISTANI ALUMNA TO IAA PRESIDENT: MEET SADIA KHAN MBA’95D

https://alumnimagazine.insead.edu/from-first-pakistani-alumna-to-ia...

Sadia Profilevestment banker, development banker, financial sector regulator, family business leader and now entrepreneur. This is the career of Sadia Khan MBA’95D: first Pakistani woman to graduate from INSEAD and new president of the world’s most international alumni organisation. She explains how being an INSEAD volunteer has played a role in her own achievements – and how the IAA is working for the benefit of all alumni.

Salamander Magazine: Do you have a secret formula for success?

Sadia Khan: Initiative. Networking. Savoir-faire. Empowerment. Attitude. Diligence… Or, for short, INSEAD! And the best way to keep that formula fresh after graduating is to join the INSEAD Alumni Association. That’s why I’ve always been so involved at a national and international level. And the network feels more vibrant today than ever before.

SM: When you returned to work in Pakistan after many years abroad, there was no National Alumni Association… So you founded one! Why?

SK: Back in 1994, I had to fly to Dubai for my INSEAD interview, because there were no graduates to interview me in Pakistan. So I realised there was a need to galvanize the small but growing number of alumni there – and to provide a much needed networking platform for the younger generation. We started with 30 members in 2007, but managed to organise high-profile events for up to 300 people. The NAA has definitely helped to build the INSEAD brand within the country.

SM: You were an INSEAD volunteer before that, though. Had you already felt the benefits?

SK: I’d been actively involved with INSEAD since graduating. While I was based in the Philippines, I started interviewing MBA candidates and discovered that it not only kept me in touch with the school’s development but also gave me the chance to interact with the next generation of business leaders.

SM: How did you get involved at an international level?

SK: I was invited to become a member of the IAA Executive Committee as VP for Asia and communications in 2012. The highlight was probably heading up the implementation of the first Global INSEAD Day in 2013. The IAA model is based on teamwork and volunteerism and it was in that spirit that I took up my current role.

SM: How did you become the global IAA President?

SK: I have to admit I was taken by surprise when the search committee approached me earlier this year! It wasn’t a role I was vying for or even contemplating at this stage of my professional life. However, I knew there was work to be done right now in enhancing the value proposition of the IAA for our alumni, and there was a great team ready to support me in this role, within the volunteer community and within the school.

SM: Why do you believe the IAA is so valuable to alumni and to the school?

SK: An active alumni association not only helps to keep the alumni energised and engaged but also contributes tremendously to the positive branding of INSEAD. Through our activities, we not only get a chance to showcase the achievements of our members but also demonstrate our deep bonding with the institution. And nothing succeeds like success. The success of the alumni boosts the reputation of the school, while in turn the success of the school enables the alumni to bask in its reflected glory. Having a strong and active alumni network is a win-win for all.

Oct 22, 2018

Riaz Haq

Carpenters Challenge Notions Of '#Women's Work' In Pakistan. Dozens of women in northern #Pakistan have learned #carpentry skills as part of a #training program to make them financially independent. #vocation https://www.rferl.org/a/pakistan-women-carpenters/29562991.html

Oct 25, 2018

Riaz Haq

#Pakistani #Hindu women in #Thar determined to change destiny through #CPEC. #China #Coal #Power https://nation.com.pk/26-Oct-2018/pakistani-women-determined-to-cha...

"It made me believe in miracles," said 24-year-old Lata Mai who drives a 60-ton dump truck in a coal-based power plant in Thar desert of Pakistan's south Sindh province, a project under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

READ MORE: Ethiopia appoints Africa's only female president

Belonging to an area where women are usually underprivileged and less educated, Mai dared to dream big.

The childhood dream of Mai, now the mother of two, was to drive a vehicle on the barren road of Thar. But she knew it was a fancy thinking that would probably never be realized, until one day her husband brought a pamphlet home which said that the Thar coal project was hiring women to drive trucks.

Mai, who had never shared her dream with anyone, hesitantly expressed her wish to apply for the post.

Her husband merely laughed at the idea, but after seeing her determination, he agreed to support her.

READ MORE: Everything feels in rhythm, says Curry after 51-point night

Naseem Memon of Sindh Engro Mining company, a member of the committee that hired Mai and dozens of other young women in Thar, told Xinhua that the women drivers are undergoing a 10-month training and will get behind the wheel in December.

"Unlike other sectors, in a coal project, most of the mining jobs are related to truck driving. When we observed that women in Thar walk two to three miles a day in temperatures as high as 50 degrees Celsius, we believed that if we bring them to job sector, they can do wonders. We were right, they did not disappoint us, they are more hardworking than their male counterparts," said Memon.

"You can imagine how CPEC has changed the lives of these women in a far flung desert of Pakistan. Women, who were utterly dependent on men, are now freely driving heavy dump trucks."

Kiran Sidhwani, a young woman living in the Thar desert, also witnessed a surprising turn in her life after she got a job opportunity in the Thar coal power project.

READ MORE: US mail bombs: who has been targeted?

"She is a young university graduate who is working as an electrical engineer with us. Apart from Sidhwani, we have also hired a female civil engineer who will join work after completing her training," Memon told Xinhua.

Pakistan's Minister for Human Rights Shireen Mazari said earlier this week that when CPEC moves beyond road construction to enter into the building process of economic zones, the standard of workforce will be raised in the country.

"As special economic zones are coming to play, multinational enterprises will bring corporate social responsibility with them. With the bringing in of great corporate social responsibility, we will see the rise and improvement in the standard of workforce, including the women workforce," said the minister.

According to the latest study of CPEC Center of Excellence, CPEC has the potential to create around 1.2 million jobs through the currently agreed projects, and the number may go up with the inclusion of new projects under its long term plan.

READ MORE: Spain Supreme Court orders trial of former Catalan leaders

The CPEC projects, including energy projects, infrastructure projects, Gwadar Port and industrial cooperation proposed under special economic zones in different provinces of the country, will immensely help reduce the unemployment rate in the country.

Analysts believe that female employment rate in CPEC is low at this stage as the project mainly offers blue collar jobs, but with the development of economic zones, more white collar job opportunities will be offered and more women workforce will take part in it.

A primary school has been established in Gwadar where 498 students including 348 girls are provided quality education to enable them to reap the benefits of CPEC-related projects in the Gwadar port.

Oct 25, 2018

Riaz Haq

Despite the strong will, they do face some practical challenges. Both Asra and Alam Khan were vocal about the poor sports training facilities in Pakistan and the lack of government support, with Asra calling sports infrastructure in the country not at par with neighbouring countries like India or Bangladesh.

Jan 3, 2019

Riaz Haq

Rising voices of #women in #Pakistan. Pakistan’s last #elections saw an increase of 3.8 million newly registered women voters. Dramatic increase follows a 2017 law requiring at least 10% female voter turnout to legitimize each district’s count. https://on.natgeo.com/2GcdyGg via @NatGeo

Many rural women are not registered for their National Identity Cards, a requirement not only to vote but also to open a bank account and get a driver’s license. In Pakistan, many women in rural and tribal areas have not been able to do these things with or without the card. In accordance with patriarchal customs and family pressures, they live in the privacy of their homes without legal identities.

Yet Pakistan’s July 2018 elections saw an increase of 3.8 million newly registered women voters. The dramatic increase follows a 2017 law requiring at least a 10 percent female voter turnout to legitimize each district’s count. Pakistan has allowed women to vote since 1956, yet it ranks among the last in the world in female election participation.

The remote tribal area that borders Afghanistan, formally called the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of northwestern Pakistan, has traditionally been least tolerant of women in public spaces, some women activists say. Yet registration in 2018 increased by 66 percent from 2013. This rise in women’s votes is a victory for women like Khaliq, who are fighting for women’s inclusion and equality in Pakistan, especially among marginalized communities in rural and tribal areas.

Encouraging more women to vote is only the beginning. Women themselves disagree over what their role should be in Pakistani society. The patriarchal, conservative mainstream dismisses feminism as a Western idea threatening traditional social structures. Those who advocate for equality between women and men – the heart of feminism – are fighting an uphill battle. They face pushback from the state, religious institutions, and, perhaps most jarringly, other women.

There are different kinds of activists among women in Pakistan. Some are secular, progressive women like Rukhshanda Naz, who was fifteen years old when she first went on a hunger strike. She was the youngest daughter of her father’s twelve children, and wanted to go to an all-girls’ boarding school against his wishes. It took one day of activism to convince her father, but her family members objected again when she wanted to go to law school. “My brother said he would kill himself,” she said. Studying law meant she’d sit among men outside of her family, which would be dishonorable to him. Her brother went to Saudi Arabia for work. Naz got her law degree, became a human rights lawyer, opened a women’s shelter in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and worked as resident director of the Aurat Foundation, one of Pakistan’s leading organizations for women’s rights. She is also the UN Women head for the tribal areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA.

Feb 8, 2019

Riaz Haq

Major General Nigar Johar Khan of the Medical Corps is only the 3rd female to rise to the 2-star general rank in Pakistan Army. She hails from a Pashtun family and is from KPK province.

https://www.geo.tv/latest/240720-nigar-johar-khan-becomes-third-wom...

Major General Nigar Johar Khan has become the third woman in Pakistan's history to hold the rank of a major general in the Pakistan Army, according to Human Rights Minister Shireen Mazari.

Mazari shared a picture of Maj Gen Nigar Khan, adding the caption: "Respect. #womenempowerment".

"She is a two-star general in Pak Army’s Medical Corps. Apart from being a doc, she is a sharp shooter too," Qamar explained.

"Pak has shown that, it is committed to gender equality and women empowerment. Gender specific jobs assigned by the ancient patriarchy are now adapting to the realities of 21st century," she added.

Jun 18, 2019

Riaz Haq

Amjad Ali, #Karachi rickshaw driver, father of six daughters sending them all to school in #Pakistan. One of his daughter Muskan just won a scholarship to study at top #business school. #education #highereducation https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=2019062115073239

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1142580970215788544

In a country where many women are still discouraged from getting an education and are married off early, Amjad Ali, a father of six daughters, and a rickshaw driver, has broken the mould by sending his daughters to Karachi’s leading universities, reports Samaa TV.

“People often mocked and criticised me, saying that girls are bound to get married and move out and to stop wasting my hard-earned money on my daughters,” he said.

But one of his daughters, Muskan, recently received a scholarship from the Institute of Business Administration, which is one of the top business schools in the country. “It was one of the happiest days of my life,” he said. “Be it a son or a daughter, the right to education is equal for all,” he believes.

Jun 22, 2019

Riaz Haq

In Pakistan, it’s middle class rising

S. Akbar Zaidi

https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/in-pakistan-its-middle-class-...

he general perception still, and unfortunately, held by many people, foreigners and Pakistanis, is that Pakistan is largely an agricultural, rural economy, where “feudals” dominate the economic, social, and particularly political space. Nothing could be further from this outdated, false framing of Pakistan’s political economy. Perhaps the single most significant consequence of the social and structural transformation under way for the last two decades has been the rise and consolidation of a Pakistani middle class, both rural, but especially, urban.

-------------------

Girls shining

Data based on social, economic and spatial categories all support this argument. While literacy rates in Pakistan have risen to around 60%, perhaps more important has been the significant rise in girls’ literacy and in their education. Their enrolment at the primary school level, while still less than it is for boys, is rising faster than it is for boys. What is even more surprising is that this pattern is reinforced even for middle level education where, between 2002-03 and 2012-13, there had been an increase by as much as 54% when compared to 26% for that of boys. At the secondary level, again unexpectedly, girls’ participation has increased by 53% over the decade, about the same as it has for boys. While boys outnumber girls in school, girls are catching up. In 2014-15, it was estimated that there were more girls enrolled in Pakistan’s universities than boys — 52% and 48%, respectively. Pakistan’s middle class has realised the significance of girls’ education, even up to the college and university level.

In spatial terms, most social scientists would agree that Pakistan is almost all, or at least predominantly, urban rather than rural, even though such categories are difficult to concretise. Research in Pakistan has revealed that at least 70% of Pakistanis live in urban or urbanising settlements, and not in rural settlements, whatever they are. Using data about access to urban facilities and services such as electricity, education, transport and communication connectivity, this is a low estimate. Moreover, even in so-called “rural” and agricultural settlements, data show that around 60% or more of incomes accrue from non-agricultural sources such as remittances and services. Clearly, whatever the rural is, it is no longer agricultural. Numerous other sets of statistics would enhance the middle class thesis in Pakistan.

Oct 16, 2019

Riaz Haq

Female Empowerment in Pakistan

ON NOVEMBER 1, 2019

https://www.borgenmagazine.com/female-empowerment-in-pakistan/

UNDP Supports High Altitude Farming

In the Pakistan territory of Gilgit-Baltistan, harsh mountain terrain makes it difficult for families to grow enough food to support themselves. It becomes especially difficult in the winter. In response, UNDP came up with a solution that helps tackle food insecurity and empower women. It has provided tunnel farms that are owned and run by local women. Tunnel farms are plastic, hooped greenhouses that protect crops from winter weather. These farms give the region access to fresh vegetables throughout all seasons.

By placing the tunnel farms in the hands of women, UNDP is supporting economic empowerment for women in the region. The women are able to make money for themselves and their families by selling the vegetables they grow in local markets. Between January and April 2019, these women were able to grow approximately 16,500 seedlings in the tunnels. Each tunnel earned approximately $247 for its produce. This income supports women, families and communities. The tunnels are an important step toward greater female empowerment in Pakistan.

UNDP Provides Training to Rural Women

In the Sultan Shah village in the Noshki district of Pakistan, UNDP is taking a different approach to helping women become economically empowered. The district suffers from severe poverty. Women often need to find employment to make ends meet for their families. Due to a lack of employment opportunities in the village, many need to travel long distances to find work.

Bibi Hajra, a recent widow, walked hours each day to be a domestic worker for wealthier families and was still not making enough to adequately support her family. She stated, “The houses where I worked were a long distance away from my own home. Each day, by the time I reached the neighbourhood, I was already exhausted — my actual job of cleaning the houses still lay ahead of me,” she said.

In response to the difficulties faced by these women, UNDP supported a stitching center to train women in marketable embroidery and sewing skills. Though this initiative is on a fairly small scale, it reflects the importance of addressing the specific needs of women in different contexts. The stitching center has had a significant impact on women in the Sultan Shah village. Bibi Hajra now making enough money to adequately support her family without traveling.

U.N. Women Fights for Equal Employment Opportunities

U.N. Women is also committed to supporting female empowerment in Pakistan. Recently, they worked with the local energy company Engro Energy Limited (EEL) to ensure equal employment opportunities for women in Sindh, Pakistan. Being rich in natural resources, there has been a lot of development for local energy companies over the past few years. This has increased employment opportunities for both men and women. Women are now working “unconventional” jobs, including transport, entrepreneurship and engineering.

EEL has committed to supporting female employment by signing the “Women’s Empowerment Principles.” These principles formally agree to help women participate fully and equally in the job force. It is important to note that the company had already set a precedent for supporting women and giving them equal job opportunities. Many women have been working as truck drivers for the company. The agreement is another way to continuing EEL’s commitment.

One woman, Rukhsana, has benefited greatly from truck driving. She stated, “Through this driving training, I gained the strength and courage to face the world,” She added that the income has had a significant impact on her family’s well being, allowing her sons to attend school. She hopes to provide them will better opportunities in the future by enabling them to go to college. EEL hopes to recruit more female truck drivers and give them an opportunity to become economically empowered.

Nov 3, 2019

Riaz Haq

BISP, Citizenship and Rights Claims in Pakistan

By Rehan Rafay Jamil

https://researchcollective.blogspot.com/2019/03/bisp-citizenship-an...

Taking Stock of Ten Years of the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP)

Over ten years since its establishment, the Benazir Income Support Progamme (BISP) has become Pakistan’s largest social safety net, providing coverage to over 5.6 million women and their households across the country. The expansion of BISP over the past decade marks an important shift in social policy in Pakistan. BISP has now been overseen by three elected governments and has resulted in a significant increase in federal fiscal allocations for social protection. Despite vocal reservations about its name expressed by some political parties, the program remains Pakistan’s largest flagship poverty alleviation program with international recognition.[1]

Third party impact evaluations of BISP have largely focused on its poverty alleviation, nutritional and gender empowerment impacts.[2] [3] These evaluations point to important reductions in poverty and improved nutritional levels for beneficiaries and their households. Oxford Policy Management’s 2016 evaluation finds reductions in BISP households’ reliance on casual labor and an increase in household savings and asset accumulation.[3]

BISP is one of the largest cash transfer programs targeted exclusively at women in the Global South, making the gender impacts of BISP important to understand. In their evaluation, Ambler and De Brauw (2017) find some changes in gender norms and attitudes amongst beneficiaries and their families. Their study finds that female beneficiaries are more likely to have greater mobility to visit friends without their spouse’s permission, are less likely to tolerate domestic violence and male members are more likely to contribute to household work.

BISP and the transition from Cash Transfer Beneficiaries to Citizens

The evaluation reports provide some evidence that BISP has also had a wider set of intended and unintended consequences in influencing beneficiaries’ access to public institutions and spaces. Perhaps the most frequently cited impact of BISP has been a marked increase in rural women’s access to computerized national identity cards (CNICs), a prerequisite for obtaining the program. CNICs can be seen as the first step to citizenship and rights claims in Pakistan. The most significant impact of the rapid increase in CNIC registration amongst BISP beneficiaries has been with regards to voting. Ambler and De Brauw (2017) find evidence that BISP beneficiaries are more likely to vote in national elections. But whether BISP beneficiaries are empowered by the cash transfer to make a wider set of rights claims and access local state services, is less clear.

In order to understand some of the changes brought about by BISP in the lives of rural women, I conducted qualitative field work, including in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with beneficiaries and their spouses, in the district of Thatta in Lower Sindh. Thatta has a high proportion of BISP beneficiaries (47 percent), being a high poverty district. The aim of the fieldwork was to develop an understanding of how beneficiaries and their families perceive of BISP and whether the program has brought about any changes in their engagement with local state services.

Nov 21, 2019

Riaz Haq

#Pakistan's younger are #women riding a #digital wave in drive for better jobs....50% of the graduates, a majority of whom are women, have found work in #software companies. https://reut.rs/3bInRhf

When Kianat Naz joined a women-friendly technology boot camp a year ago, she had no idea it would completely change her life and her views on how women can work in conservative Pakistan.

Naz, 22, had never ventured far from her home in Orangi Town in Karachi, one of the five largest slums of the world, but was feeling dissatisfied with her current teaching job.

So she signed up for tech programme called TechKaro, an initiative by Circle, a social enterprise that aims to improve women’s economic rights in Pakistan, and is now working fulltime for a software company.

Naz said the course was challenging in many ways but she soon found that the women on the training were just as good as the men at tech skills like coding, web development and digital marketing, and also at presenting themselves at interviews.

“From developing our CVs, to giving us tips on dressing for work, to conducting ourselves during an interview and how to battle some sticky questions ... we were groomed for everything,” said Naz.

Women make up about 25% of Pakistan’s labour force, one of the lowest in the region, according to the World Bank.

It has set a target to increase this to 45%, calling for more childcare and a crackdown on sexual harassment to encourage more women out to work and boost economic growth.

In Pakistan, women represent only 14% of the IT workforce, according to a 2012 study by P@SHA, the Pakistan Software Houses Association for IT and IT-enabled services (ITeS).

GAP IN THE MARKET

Sadaffe Abid, chief executive of Circle, set up TechKaro with the help of a few private foundations in 2018 seeing this gender gap, and took on 50 trainees in the first year of which 62% were women and 75 in 2019 including 66% women.

Abid, who previously worked for a micro-finance institution, said she was delighted that women like Naz were proving that women could succeed in the tech world.

“I am a firm believer that one of the most powerful uses of technology is to bring it to young women, especially from under-served communities, to unlock their talents, resourcefulness and creativity,” said Abid.

“People told me I won’t find women, or women will drop out in high numbers, or after completing the course, women won’t find employment as the industry will not be open to hiring this unique diverse group with no degree in computer science.

“But I would say 50% of the graduates, a majority of whom are women, have found work in software companies,” said Abid, who also brought She Loves Tech to Pakistan, one of the world’s largest women and startup competitions globally.

TechKaro is one of the latest programmes in the country aimed at helping women crack the traditionally male domain.

CodeGirls Pakistan, a Karachi-based boot camp, trains girls from middle and low-income families in coding and business skills.

In 2017, a six-week camp SheSkills taught women everything from web development and digital design to social media marketing.

After attending the TechKaro course, Naz found work earlier this year at an IT company earning double the salary she was getting as a teacher but which meant leaving her neighbourhood, using public transport, and working side-by-side with men.

“I had never ventured out on my own and I was dead scared the first time I had to do it, but now it is just fine,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation said in an interview by telephone from Orangi Town.

“The rest of Karachi is not quite the big bad wolf I’d imagined it to be,” said Naz who navigated an app-based transit startup to reduce her travel time by two hours a day.

“It gave me a lot of confidence when I asked my employers if they would have a problem with my wearing the niqab (a veil that fully covers the face) and they said they were only interested in my work performance.”

Apr 27, 2020

Riaz Haq

#Karachi-based #Pakistani Physician Dr Anita Zaidi appointed President of #GenderEquality at Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She has also served as director of #Vaccine Development, Surveillance, and Enteric and Diarrheal Diseases programs. https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/671634-dr-anita-zaidi-appointed-a...

Pakistani Physician Dr Anita Zaidi has been appointed as the new president Gender Equality at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

In a remarkable feat for Pakistan, Zaidi is now a part of the Executive leadership team (ELT), included among the six other foundation presidents.

Zaidi has also served as the director of the Vaccine Development, Surveillance, and Enteric and Diarrheal Diseases programs at Bill Gates and Melinda Foundation.

"Her team’s work is focused on vaccine development for people in the poorest parts of the world, surveillance to identify and address causes of death in children in the most under-served areas, and significantly reducing the adverse consequences of diarrheal and enteric infections on children’s health in low and middle-income countries," read the text on the official site of Bill Gates and Melinda Foundation.

Anita obtained her medical degree from the Aga Khan University in Karachi, residency training in pediatrics and fellowship training in medical microbiology from Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

She undertook further training in pediatric infectious diseases from Boston’s Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and Masters in Tropical Public Health from the Harvard School of Public Health.

"In 2013 Anita became the first recipient of the $1 million Caplow Children’s Prize for work in one of Karachi’s poverty-stricken fishing communities to save children’s lives. She was nominated as a notable physician of the year in 2014 by Medscape," read the website.

Jun 12, 2020

Riaz Haq

Pakistan-born #scientist becomes first woman & #Pakistani to head biology and medicine section at Max Planck Society, #Germany’s most prestigious research body. It has 18 #Nobel laureates to its credit, at par with the best research institutions worldwide. https://www.dawn.com/news/1569093

KARACHI: Pakistan-born scientist Asifa Akhtar has become the first international female vice president of the biology and medicine section at Germany’s prestigious Max Planck Society.

The Max Planck Society is Germany’s most successful research organisation. Since its establishment in 1948, no fewer than 18 Nobel laureates have emerged from the ranks of its scientists, putting it on a par with the best and most prestigious research institutions worldwide.

During her term of office, Ms Akhtar will be in charge of the institutes of the sections and will also be the contact person for the Max Planck Schools.

“My heart beats for the young scientists,” the society’s website quoted Akhtar as saying.

“Academic science is a beautiful example of integration because you have people from all over the world exchanging knowledge beyond boundaries, cultures or prejudice,” she told the society in an interview.

As the vice president, Ms Akhtar also wants to advance the issue of gender equality. “Gender equality needs to be worked on continuously. There are outstanding women in science and we should make all the efforts and use our resources to win them for the Max Planck Society,” she said.

To enable gender diversity in various career domains, she said, the society needed to be more accommodating and understanding. “If we want women to progress in science, we need to enable practical solutions such as childcare and time-sharing or home office options,” she added.

Born in Karachi, she obtained her doctorate at the Imperial Cancer Research Fund in London, UK, in 1997.

She then moved to Germany, where she was a Postdoctoral fellow at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg and the Adolf-Butenandt-Institute in Munich from 1998 to 2001.

Ms Akhtar was awarded the Early Career European Life Science Organisation Award in 2008, EMBO membership in 2013, and the Feldberg Prize in 2017. She was also elected as a member of the National Academy of Science Leopoldina in 2019.

Jul 15, 2020

Riaz Haq

#Pakistani #women break dating taboos on #Tinder. Though casual #dating for women is still frowned upon in socially conservative & heavily patriarchal Pakistan, attitudes are rapidly changing in the country's cities. #Karachi #Lahore #Islamabad #Pakistan https://www.dw.com/en/pakistan-women-tinder/a-54509792

Casual dating for women is often frowned upon in Pakistan's male-dominated society. However, dating apps such as Tinder are challenging norms and allowing women to take more control over their sexuality.

Faiqa is a 32-year-old entrepreneur in Islamabad, and, like many young single women around the world, she uses dating apps to connect with men.

Although casual dating for women is still frowned upon in socially conservative and heavily patriarchal Pakistan, attitudes are rapidly changing in the country's cities.

Faiqa has been using the dating app Tinder for two years, and she said although the experience has been "liberating," many Pakistani men are not used to the idea of women taking control of their sexuality and dating lives. Pakistani women are often expected to preserve a family's "honor."

"I've met some men on Tinder who describe themselves as 'open minded feminists,' yet still ask me: 'Why is a decent and educated girl like you on a dating app?'" Faiqa told DW.

Online dating grows in South Asia

India leads South Asia's online dating market, and Pakistan is slowly catching on. A study by the Indonesian Journal of Communication Studies found that most of Pakistan's Tinder users come from major cities including Islamabad, Lahore and Karachi and are usually between 18 and 40 years old.

Other dating apps are also growing in popularity. MuzMatch caters exclusively to Muslims looking for a date. Bumble, despite being relatively new to the online dating market, is a favorite among many Pakistani feminists, as women initiate the first conversation.

"There are fewer men on Bumble, therefore it somehow feels safer to use. Tinder is well-known and someone you know could see you, making it uncomfortable," said Nimra, a student from Lahore.

However, many young women in Pakistan use apps because it makes dating more private.

"With a dating app, a woman can choose if she wants a discreet one night stand, a fling, a long-term relationship etc. It is hard for women to do this openly in our culture, which is why dating apps give them an opportunity they won't find elsewhere," said Nabiha Meher Shaikh, a feminist activist from Lahore.

Exploring sexuality in a conservative society

Sophia, a26-year old researcher from Lahore, told DW she uses Tinder to explore her "sexuality without constraints."

"I don't care if people judge me. Society will always judge you, so why bother trying to please them?" she said.

However, not all female Tinder users are as open as Sophia. Most Tinder profiles of Pakistani women do not disclose their full identity, with photographs showing only cropped faces, close-up shots of hands or feet, faces covered with hair or only painted fingernails.

"If we put up our real names or photographs, most men tend to stalk us. If we don't respond, they find us on social media and send weird messages," said 25-year-old Alishba from Lahore.

She also pointed out dating double standards, explaining that married men on Tinder often use their "broken" marriage as an excuse to date other women.

Aug 31, 2020

Riaz Haq

Pakistan-born Ayesha read economics at Harvard University and later moved to New York City to pursue a career in Wall Street. She says, “In my field of work, being in Singapore makes a lot of sense. The country believes that for future economic growth, it needs to invest in technology. It is also a great gateway to the fastest growing markets in Asia and because it is a smaller country, any start-up here is international from day one because the mentality is to go out there and be an adventurer.”

https://sg.asiatatler.com/society/parag-ayesha-khanna-on-travel-tec...

More than building a business empire, Ayesha, who is a member of the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Councils, emphasises the importance of the human element in her work. “When I was younger, I worked in the area of human rights so I have always had a human-centred approach to using and living with technology,” says the 46-year-old, who also serves on the board of Singapore’s Infocomm Media Development Authority.

Her father was a civil servant in Pakistan and improving the lives of people was a big topic of conversation when she was a child, she explains. “I believe that the true purpose of AI is to amplify human potential. For example, with the coronavirus affecting schools and interrupting student journeys, how can we use AI to better teach students through personalised learning? Or in healthcare, how can AI assist doctors in their diagnosis or help assistants work locally with the remote supervision of doctors?”

Addo AI is currently working with a government agency from another country to develop a programme that can identify coronavirus risk locations to better divert hospital resources. She says, “My love for technology is deeply rooted in its capacity to empower citizens.”

As for the nomadic Parag, who was born in India and grew up in the United Arab Emirates, US and Germany, he found Singapore to be “by far the best” among a handful of global cities that he wanted to live in as an “urbanist”. A widely cited global intellectual, much of his life work centres around influencing the influential to build a “multipolar equilibrium”.

“I’d like an end to the cycles of superpower competition and their violent rise and decline. Since my first book, I’ve been writing non-stop about how for the first time in history, we live in a global system that is truly multipolar and multi-civilisational at the same time. Governments need to accommodate each other in order to preserve geopolitical equilibrium,” says the founder and managing partner of FutureMap, a data- and scenario-based strategic advisory firm that offers tailored briefings to government leaders and corporate executives on global markets and trends.

Sep 2, 2020

Riaz Haq

Best of 2019: A woman farmer shows the way |The Third Pole

https://www.thethirdpole.net/2019/12/25/best-of-2019-a-woman-farmer...

https://www2.unwomen.org/-/media/field%20office%20eseasia/docs/publ...

Almas Perween may seem diminutive, but a great deal of responsibility rests on her shoulders. She is a farmer, and a trainer of farmers, a big responsibility for a woman from a village whose name is just a number – Chak #224/EB. Her farm is about 100 kilometres from the historic city of Multan, in the Vehari district of Pakistan’s Punjab province. In many ways Perween epitomises this year’s International Women’s Day’s theme of “Think Equal, Build Smart, Innovate for Change”, putting innovation by women and girls, for women and girls, at the heart of efforts to achieve gender equality.

Challenging gender roles

“Why is cotton-picking always a woman’s job?” was the first thing I heard her say. The question carried within it the challenge to traditional gender roles. While Perween is happy to take on the mantle of what is traditionally seen as men’s work, her question took this further, asking why men cannot do what is traditionally done by women.

It has long been said that the soft, fluffy staple fibre of cotton that grows in a boll can only be picked by women’s dainty hands. Perween refused to accept this, claiming it was “just an excuse not to work”.

“It’s literally back-breaking work and takes a heavy health toll on the women,” she said. Drawing from her experience, she added, “village women work longer hours in a day than men”.

Her experience is borne out by research done elsewhere. A 2018 report on the status of rural women in Pakistan said agricultural work has undergone “feminization” employing nearly 7.2 million rural women, and becoming the largest employer of Pakistani women workers. Yet their multidimensional work with “lines between work for economic gain and work as extension of household chores (livestock management) and on the family farm” are blurred and “does not get captured”.

The report pointed out that for women in the agricultural sector (primarily concentrated in dairy and livestock) the “returns to labour are low: only 40% are in paid employment and 60% work as unpaid workers on family farms and enterprises. Their unpaid work is valued (using comparative median wages) at PKR 683 billion (USD 5.5 billion), is 57% of all work done by women, and is 2.6% of GDP of the country.”

Cotton is one of the many crops grown on Perween’s fields. She manages 23 acres of farmland (of which eight acres belong to her mother). With her brother – three years her senior – the family grows maize, wheat, sugarcane and cotton.

-----------------

Despite the success, it has not always been easy for Perween to take the risks she has. She has been lucky to have the full backing of her family. It is not just her brother’s trust, but also her father’s firm support in the face of criticism from both villagers and the wider family, that has helped her find her own path.

“It has not been easy,” she said, “but it is not impossible either,” Perween says, with a note of triumph in her voice.

Sep 18, 2020

Riaz Haq

Enabling more Pakistani women to work

UZMA QURESH|MAY 07, 2019

https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/enabling-more-pak...

There is a broad consensus that no country can progress without the full participation of women in public life .

Most of the positive attributes associated with development – rising productivity, growing personal freedom and mobility, and innovation – require increasing the participation of excluded groups.

Pakistan stands near the bottom of women’s participation in the workforce. This lack of participation is at the root of many of the demographic and economic constraints that Pakistan faces.

It is in that context that the World Bank, in its Pakistan@100 initiative, has identified inclusive growth as one of the key factors to the country’s successful transition to an upper-middle income country by 2047.

Pakistan’s inclusive growth targets require women’s participation in the workforce to rise from a current 26 percent to 45 percent .

Women’s participation rate has almost doubled in 22 years (1992-2014) but the increase isn’t happening fast enough and with much of our population in the youth category, we need to rapidly take measures to address gaps in women’s work status to achieve our goal.

Focus should be on the following priority areas:

Increase access to education, reproductive health services: Half of Pakistani women have not attended school. Presently only 10 percent of women have post-secondary education whereas their chances of working for pay increase three-fold with post-secondary education compared to women with primary education. More educated women are also more likely to get better quality jobs.

Pakistan also couldn’t meet the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) target of reducing maternal mortality ratio to 150. The government must implement anti early age marriage laws and invest in transforming behaviors of parents and society on such practices. This will allow girls to have more years of education and have better reproductive health outcomes. Fertility decline related behavioral change efforts are also critical in addition to improved service delivery to enable women to have healthier lives and find better economic opportunities .

Unpaid Care Work and informal economy: Women are 10 times more involved in household chores, child and elderly care than men in Pakistan. This leads to women being more time poor and having less time to spend in gaining skills and getting jobs.

Social norms also do not support women’s involvement in economic activity outside their homes and this forces them to either fall back in the informal sector (women are heavily concentrated in it) and rely upon unskilled or low skilled jobs (mostly home-based) or to simply not participate in the wider economy. Adoption and effective implementation of home-based and domestic workers laws can address informal economy issues of extremely low wages and lack of access to social security.

The burden of unpaid care work with high fertility rate is in many ways at the root of all of these problems because more children result in more unpaid care work and it also means that women will be in poorer health conditions especially in lower and middle-income levels rendering them unable to acquire the skills needed for gainful employment opportunities.