PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

Pakistan-born, Harvard-educated economist Ms. Saadia Zahidi, author of "50 Million Rising", is currently a member of the executive committee and the head of Education, Gender and Work at the World Economic Forum, Davos, Switzerland. She told Kai Ryssdal of APR Marketplace of her visit to a gas field in Pakistan with her geophysicist father where she met Nazia, a woman engineer who inspired her.

|

| Saadia Zahidi |

The "50 Million" in the title of her book refers to the 50 million Muslim women who have joined the work force over the last 15 years bringing the total number of working women in the Muslim world to about 155 million.

In her book, Saadia talks about her father being the first in his family to go to university. He believed in girls' education and career opportunities. She recalls him suggesting that "my sister could become a pilot because the Pakistan Air Force had just starting to train women. Another time he speculated that I could become a news anchor because Pakistan Television, the state-owned television network, had started recruiting more women". Here's an excerpt of her book:

"This shift has not been limited to Pakistan. A quiet but powerful tsunami of working women has swept across the Muslim world. In all, 155 million women work in the Muslim world today, and fifty million of them--a full third--have joined the work force since the turn of the millennium alone, a formidable migration from home to work in the span of less than a generation".

Saadia Zahidi has devoted parts of her book to her experiences in Pakistan where she visited a McDonald's restaurant and found many women working there. A woman also named Saadia working at McDonald's restaurant in Rawalpindi is featured in the book. Here's an excerpt:

"For young women like Saadia, seeing their efforts rewarded in the workplace, just as they were in school and university, can be eye-opening and thrilling and lead them to become even more motivated to work. The independent income is an almost unexpected bonus. I asked Saadia how she spends her earnings and whether she saves. She gives 30 percent of her income to her parents, she said, and the rest she spends as she pleases: mostly on gifts to her parents, sisters, and friends as well as on lunches and dinners out with friends and gadgets like her cell phone—all new luxuries for her. She said that she has no interest in saving because her parents take care of housing and food, just as she expects her husband will do after she marries. So her disposable income is wholly hers to spend, allowing her to contribute to the household budget while also buying luxuries that were previously unimaginable for her parents, without adding a burden to them."

Challenging the stereotypes about Muslim women, Saadia cites an interesting statistic: In Saudi Arabia, out of all of the women that could be going to university, 50 percent are. And that is higher than in China, in India, in Mexico, in Brazil.

I wrote a post titled "Working Women Seeding a Silent Revolution in Pakistan" in 2011. It's reproduced below in full:

While Fareed Zakaria, Nick Kristoff and other talking heads are still stuck on the old stereotypes of Muslim women, the status of women in Muslim societies is rapidly changing, and there is a silent social revolution taking place with rising number of women joining the workforce and moving up the corporate ladder in Pakistan.

"More of them(women) than ever are finding employment, doing everything from pumping gasoline and serving burgers at McDonald’s to running major corporations", says a report in the latest edition of Businessweek magazine.

Beyond company or government employment, there are a number of NGOs focused on encouraging self-employment and entrepreneurship among Pakistani women by offering skills training and microfinancing. Kashf Foundation led by a woman CEO and BRAC are among such NGOs. They all report that the success and repayment rate among female borrowers is significantly higher than among male borrowers.

In rural Sindh, the PPP-led government is empowering women by granting over 212,864 acres of government-owned agriculture land to landless peasants in the province. Over half of the farm land being given is prime nehri (land irrigated by canals) farm land, and the rest being barani or rain-dependent. About 70 percent of the 5,800 beneficiaries of this gift are women. Other provincial governments, especially the Punjab government have also announced land allotment for women, for which initial surveys are underway, according to ActionAid Pakistan.

Both the public and private sectors are recruiting women in Pakistan's workplaces ranging from Pakistani military, civil service, schools, hospitals, media, advertising, retail, fashion industry, publicly traded companies, banks, technology companies, multinational corporations and NGOs, etc.

Here are some statistics and data that confirm the growth and promotion of women in Pakistan's labor pool:

1. A number of women have moved up into the executive positions, among them Unilever Foods CEO Fariyha Subhani, Engro Fertilizer CFO Naz Khan, Maheen Rahman CEO of IGI Funds and Roshaneh Zafar Founder and CEO of Kashf Foundation.

2. Women now make up 4.6% of board members of Pakistani companies, a tad lower than the 4.7% average in emerging Asia, but higher than 1% in South Korea, 4.1% in India and Indonesia, and 4.2% in Malaysia, according to a February 2011 report on women in the boardrooms.

3. Female employment at KFC in Pakistan has risen 125 percent in the past five years, according to a report in the NY Times.

4. The number of women working at McDonald’s restaurants and the supermarket behemoth Makro has quadrupled since 2006.

5. There are now women taxi drivers in Pakistan. Best known among them is Zahida Kazmi described by the BBC as "clearly a respected presence on the streets of Islamabad".

6. Several women fly helicopters and fighter jets in the military and commercial airliners in the state-owned and private airlines in Pakistan.

Here are a few excerpts from the recent Businessweek story written by Naween Mangi:

About 22 percent of Pakistani females over the age of 10 now work, up from 14 percent a decade ago, government statistics show. Women now hold 78 of the 342 seats in the National Assembly, and in July, Hina Rabbani Khar, 34, became Pakistan’s first female Foreign Minister. “The cultural norms regarding women in the workplace have changed,” says Maheen Rahman, 34, chief executive officer at IGI Funds, which manages some $400 million in assets. Rahman says she plans to keep recruiting more women for her company.

Much of the progress has come because women stay in school longer. More than 42 percent of Pakistan’s 2.6 million high school students last year were girls, up from 30 percent 18 years ago. Women made up about 22 percent of the 68,000 students in Pakistani universities in 1993; today, 47 percent of Pakistan’s 1.1 million university students are women, according to the Higher Education Commission. Half of all MBA graduates hired by Habib Bank, Pakistan’s largest lender, are now women. “Parents are realizing how much better a lifestyle a family can have if girls work,” says Sima Kamil, 54, who oversees 1,400 branches as head of retail banking at Habib. “Every branch I visit has one or two girls from conservative backgrounds,” she says.

Some companies believe hiring women gives them a competitive advantage. Habib Bank says adding female tellers has helped improve customer service at the formerly state-owned lender because the men on staff don’t want to appear rude in front of women. And makers of household products say female staffers help them better understand the needs of their customers. “The buyers for almost all our product ranges are women,” says Fariyha Subhani, 46, CEO of Unilever Pakistan Foods, where 106 of the 872 employees are women. “Having women selling those products makes sense because they themselves are the consumers,” she says.

To attract more women, Unilever last year offered some employees the option to work from home, and the company has run an on-site day-care center since 2003. Engro, which has 100 women in management positions, last year introduced flexible working hours, a day-care center, and a support group where female employees can discuss challenges they encounter. “Today there is more of a focus at companies on diversity,” says Engro Fertilizer CFO Khan, 42. The next step, she says, is ensuring that “more women can reach senior management levels.”

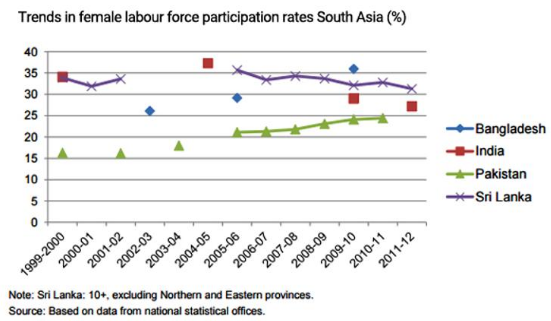

The gender gap in South Asia remains wide, and women in Pakistan still face significant obstacles. But there is now a critical mass of working women at all levels showing the way to other Pakistani women.

I strongly believe that working women have a very positive and transformational impact on society by having fewer children, and by investing more time, money and energies for better nutrition, education and health care of their children. They spend 97 percent of their income and savings on their families, more than twice as much as men who spend only 40 percent on their families, according to Zainab Salbi, Founder, Women for Women International, who recently appeared on CNN's GPS with Fareed Zakaria.

Here's an interesting video titled "Redefining Identity" about Pakistan's young technologists, including women, posted by Lahore-based 5 Rivers Technologies:

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Status of Women in Pakistan

Microfinancing in Pakistan

Gender Gap Worst in South Asia

Status of Women in India

Female Literacy Lags in South Asia

Land For Landless Women

Are Women Better Off in Pakistan Today?

Growing Insurgency in Swat

Religious Leaders Respond to Domestic Violence

Fighting Agents of Intolerance

A Woman Speaker: Another Token or Real Change

A Tale of Tribal Terror

Mukhtaran Mai-The Movie

World Economic Forum Survey of Gender Gap

Riaz Haq

Breaking barriers: Women fuel change at Pakistan’s male-dominated petrol pumps

https://www.arabnews.com/node/2597977/pakistan

ISLAMABAD: Clad in a crisp blue uniform and gripping the nozzle with practiced ease, Sumeera Bibi pumped fuel into the tank of a car, gesturing to the driver to check the reading on the dispenser machine.

While fuel stations in Pakistan have been traditionally staffed by men, there is a growing movement toward gender inclusivity, with some stations now employing women like Sumeera as attendants.

One notable example was the launch last year of Pakistan’s first all-female staffed fuel station, located in Johar Town, Lahore.

In the federal capital of Islamabad also, hundreds of women are now working alongside male staff at fuel stations.

“Since getting this job, I have been able to care for my children on my own and overcome all my problems,” Sumeera, a mother of five, told Arab News on Monday at a Pakistan State Oil station on Constitution Avenue, home to major government buildings and embassies.

Apr 22

Riaz Haq

Pakistan's women fight to enter the labor force

In Pakistan, where just 23% of women are employed, female professionals like Dr. Sobia Yaqub are challenging deep-rooted norms. As an oncologist and educator, she’s part of a growing movement proving that education and opportunity can reshape the future for women — and the nation.Breaking Barriers: Women in Pakistan's Workforce

In Pakistan, only about 20% of women manage to enter the workforce – a stark reminder of the societal and structural barriers they face. Cultural conservatism often discourages women from seeking employment – but access to employment is a fundamental right and a key driver of gender equality. The story of Dr. Sobia Yaqub, an oncologist in Lahore, highlights both the challenges and the possibilities. As a highly qualified medical professional and university lecturer, she has had to overcome workplace prejudice and family traditions that once kept women confined to the home. Her story reflects a growing shift in attitudes, as more women challenge traditional roles and seek professional success.

Education: The Key to Empowerment

Dr. Yaqub's success is rooted in education. She attended a Care School, one of nearly 900 institutions in Pakistan that provide free, high-quality education to children from low-income families. These schools are instrumental in promoting gender equality by encouraging girls to pursue their ambitions. Teachers and parents are increasingly recognizing the importance of educating girls – for personal growth and the country's economy and social development. Entrepreneurs like Seema Aziz and educators like Maria Umar further demonstrate how women can inspire others by creating opportunities.

Can Pakistan Improve Its Female Employment Rate?

Yes – but it requires a multi-faceted approach. Education must be prioritized, especially for girls from disadvantaged backgrounds – while challenging gender stereotypes, supporting women through mentorship and role models are also key. With consistent investment in education and societal change, Pakistan can raise its female labor force participation rate beyond the current 23% and unlock more of its economic potential.

Jun 25

Riaz Haq

ADB Grants 350 Million Loan to Boost Women Entrepreneurship in Pakistan

https://www.asiabusinessoutlook.com/news/adb-grants-350-million-loa...

Pakistan has secured a USD 350 million loan from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) to enhance financial access for women. This will also be promoting women-led entrepreneurship. The funding includes a USD 300 million policy-based loan and a USD 50 million financial intermediation loan aimed at improving access to finance for women across the country.

Pakistan received 350 million US dollars from the Asian Development Bank to support women's entrepreneurship

The funding includes 300 million policy-based and 50 million financial intermediation loans

The program aims to reach over two million women and boost their role in the economy

This initiative is a key step in addressing the significant gender gap in Pakistan’s economy, where the country ranks second-lowest out of 146 economies in the Global Gender Gap Index 2024. The program is part of Pakistan’s broader efforts under its Country Partnership Strategy 2021–2025, which emphasizes inclusive economic growth and gender equality.

Sani Ismail, ADB Director, stated, “The program is ambitious with a goal to reach out to over two million women in Pakistan to help them fulfill their potential, through a combination of access to finance, inclusive legal and policy reforms, and expanding capacity for entrepreneurship.”

This funding is expected to play a crucial role in empowering women by providing them the financial tools and institutional support needed to participate more actively in the economy, ultimately contributing to sustainable development and social upliftment in Pakistan.

Jun 25